76 (top), and 77 (3 images; bottom)

![A Public Reception of Mr. R.W. Emerson on His Return Home from Europe Will be given by the Citizens of Concord … [printed broadside], 1873.](/uploads/scollect/Emerson_Celebration/Em_Con_76_150dpi_540Wpix.jpg)

|

FIRE AT BUSH (1872)

AND CONCORD’S RESPONSE

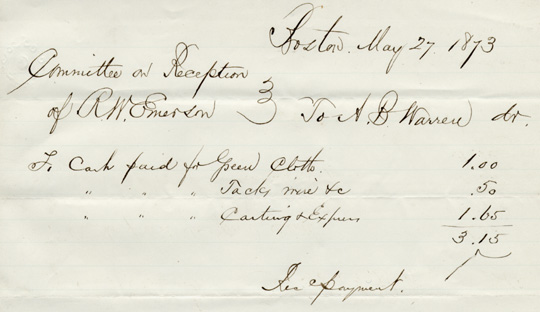

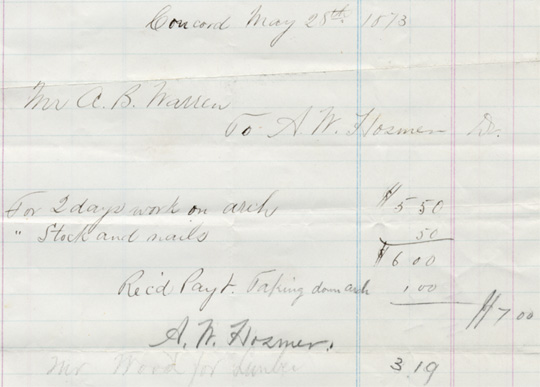

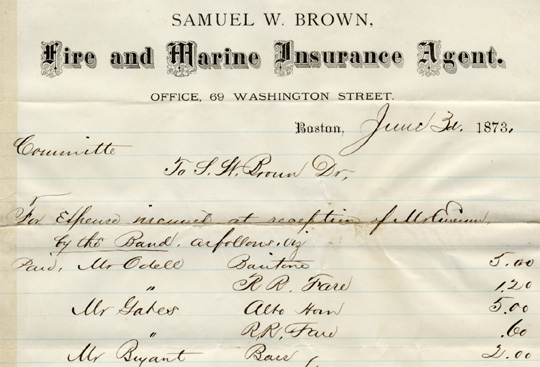

76. A Public Reception of Mr. R.W. Emerson on His Return Home from Europe Will be given by the Citizens of Concord … [printed broadside], 1873. Letterpress on paper. 77. Committee on Reception of R.W. Emerson. Records

(three receipts for supplies purchased and work done in preparation for

the reception of Emerson on Tuesday, May 27, 1873), May 27, May 28, and

June 3, 1873. Ink on paper; one receipt on letterhead.

Sleeping on the second floor of Bush, Emerson was awakened by the crackling of flames and the smell of smoke at 5:30 in the morning on July 24, 1872. He shouted to wake up Lidian (who slept on the first floor), dressed hastily, and ran out into the rainy morning to rouse the neighbors. The town mobilized quickly. The First Parish bell alerted the Fire Department. Sam Staples prevented Lidian from going upstairs to rescue her daughter Ellen’s possessions (Ellen was not at home at the time), but firefighters and villagers managed to haul a great deal from the burning house. Ellen’s piano was removed to the nearby Staples home. Food, clothing, and furniture were saved, as were Emerson’s manuscripts (some gathered up by Louisa May Alcott and her sister May) and most of his books. Unfortunately, family papers stored in the attic, where the fire had started, were destroyed, and the house itself was badly damaged. The manuscript records of Concord’s Engine Company No. 1 offer no explanation as to how the blaze started. In annotating his father’s July 24th journal entry about the fire (consisting of the two words “House burned”), Edward Emerson stated that it was “almost surely” started by the kerosene lamp of a newly hired domestic “prowling” in the attic at night. The July 25th issue of the Boston Daily Advertiser suggested another possible cause: “It is supposed that the fire originated in a defective flue, that it caught on Tuesday morning and had been smouldering ever since.” Despite equipment problems (specifically, a shortage of functioning hose), Concord firemen had taken significant risks to save what they could of the Emersons’ effects. The family appreciated what they had done. Emerson wrote a letter to the Fire Department on July 29th to express his thanks for “the able, hearty, and in great part successful exertion in our behalf, in resisting and extinguishing the fire, which threatened to destroy my house on Wednesday morning last.” Lidian, too, was grateful for the kindness shown them by their fellow Concordians. She wrote to a friend, “We have received such warm expressions of kindness from our friends, and have witnessed such disinterested action and brave daring in our town’s people, that we feel … as if Concord was a large family of personal friends and well-wishers.” After the fire was put out, the Emersons were taken to the Monument Street home of Judge John Shepard Keyes, who invited them to remain for an extended period. They turned down the invitation and accepted that of Emerson’s kinswoman Elizabeth Ripley, who lived at the Manse. Judge Hoar obtained space in the Court House for Emerson’s books and papers, so that the dispirited man might continue to write. Francis Cabot Lowell, one of Emerson’s Harvard classmates, personally delivered a $5,000 check (the gift of himself and several other friends) to offset expenses incurred by the fire. Soon after, Judge Hoar presented Emerson with a gift of more than twice the amount of the first, collected from friends to fund a trip to Egypt. In October, with Ellen as companion, Emerson sailed for England. He visited London, Paris, Florence, Rome, and Egypt, saw his old friend Thomas Carlyle for the final time, and met John Ruskin and Robert Browning. Back in Concord, John Shepard Keyes supervised repairs to Bush. In the spring of 1873, Lidian Emerson and daughter Edith Forbes threw themselves into redecorating and furnishing the house in time for Emerson’s return. Emerson and Ellen sailed home on the Olympus, arriving in Boston late in May. Concord had planned a surprise welcome for them. On Tuesday, May 27th, detained by ruse on the ship until the town was ready to receive them, they took the 2:30 Fitchburg train. Emerson was deeply moved and more than a little confused when he stepped off the train at the Concord Depot and encountered a cheering crowd and ringing bells. A band had been hired, and a welcoming arch built by the gate of Bush. A procession of citizens and schoolchildren escorted four carriages—the final one bearing Emerson, Ellen, and the Forbeses—to the house, where Lidian waited. On their arrival, the accompanying children sang “Home Sweet Home.” The town could hardly have shown its affection in a more emotional way. According to Edward Emerson, his father addressed the crowd at the gate of his home with the words, “My friends! I know that this is not a tribute to an old man and his daughter returned to their house, but to the common blood of us all—one family—in Concord!”

No image in this online display may be reproduced in any form, including electronic, without permission from the Curator of Special Collections of the Concord Free Public Library.

Next Entry - Back to Section VII Contents Listing - Back to Exhibition Introduction - Back to Exhibition Table of Contents |