Concord Houses: How They Grew

Concord Journal, December 3, 1959

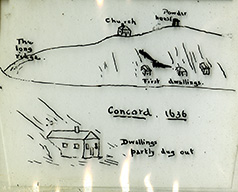

If you were going to make a model of Concord as it looked in its first century, you would show the Millpond and three roads, each with its row of houses, Walden Street going around the South Quarter Cemetery toward Academy Lane, and the North Road, going toward the river at the North Bridge, along the ridge at right angles to Lexington Road.

Within a half mile of the meeting house, which stood nearer the Hill Burying Ground than the present First Parish, were the house lots of the first settlers, close together for convenience and safety. The lots were of three to ten acres and ran down to the Millbrook from the ridge above the Bay Road and from the other ridge above the North Road, also to the brook from the Walden Street side. Water was of great importance. The barns were built across so the cattle could go down to drink.

The first houses were not log cabins, for the skill needed to build a log cabin was a Scandinavian skill—the skill of a people who lived near big forests.

In England, wood was scarcer and more valuable. The log had to be sawed into a large number of boards, which covered more space than the log itself could cover. The English carpenters were used to building with boards, with brick and stone, with thatch and with wattles. Some of the settlers were skilled carpenters accustomed to squaring logs into timbers and sawing boards in a sawpit. As time went on they set up sawmills wherever there was a fall of water and used the spring high water in these small millponds to run the saws, grinding grain with the same power.

A surveyor in Woburn named Edward Johnson wrote a book about 1650 called The Wonder Working Providence in which he described how the special favor of the Lord had helped the early settlers get established. Some of the Concord settlers, he said, lived at first in caves in the gravelly hillside, making a doorway with timbers and a roof of cross timbers with sods and gravel above.

This gave them shelter while they were getting the timbers ready for a better house. Rev. Peter Bulkeley remained in Cambridge for a year or more while Thomas Dane, whom he had engaged in England as a carpenter and sawyer, and whose passage over he had probably paid, was working on his house. This house was more elaborate then the ordinary man would need but it was a model to which the ordinary man would attain, given time. It had a 20 feet square “family” room as we would say nowadays (they called it a hall), with a huge fireplace on one side and in front of the chimney, which might be 10 or 12 feet square, a small entry and staircase. To the left was a similar room for formal use. The house was built directly on the ground with the sills resting on stones to keep them from dampness. The cellar was simply an excavation, reached by a rough ladder, in which food could be kept from freezing.

The first houses of poorer people contained just one room with a loft above. The first chimney was improvised from woven twigs daubed from clay and, as the clay dried and cracked out, became a terrible fire hazard.

Clay for brick making was soon found in Concord, in the big bowl between Lexington Road and Virginia Road. Clay pits were soon dug out and, on the mound at the end of Shady Lane, bricks were made before 1650. The high land in the midst of the clay fields, was called Brick-kiln Island in the early deeds of Eliphalet Fox. After the brick kilns and the saw mills were in operation, house building became easier and the usual procedure was to get out the logs in the winter, take them to the nearest sawmill and whenever there was time in the summer, hew out the beams for the house.

Neighbors would come to the house raising to help lift the heavy beams into place and drive in the wooden pegs, called tree nails, (or later trunnels). Temporary props would hold the beams at the center of the house until the mason could come to build the chimney. In these earlier houses the center beams rested directly on the bricks of the chimney. Bricks were valuable but might be exchanged for labor or for fire-wood to keep the kilns going. Lime for mortar was made on Estabrook Road.

Nails were the most expensive item. Hand forged and imported from England, they took cash to buy and the early ironworks in Quincy and Saugus found a ready market for nails. As you know, the Saugus Ironworks people made iron for a time out here in the country at the falls of the Assabet. Some bog-ore was found in Concord Meadows, but when it ran out, the ironworks failed.

However here were the necessities for house building and by 1720, Concord citizens all had substantial houses.

The oldest Assessor’s list for Concord still in existence is that for 1717 (the town was 80 years old), its 293 male inhabitants over 21 already spread throughout the six miles square, including half of Bedford and two-thirds of Lincoln.

The first settlers had divided the town into thirds, each section was divided up into farms by the families who had original house lots in that quarter, and the sons and grandsons established themselves out on the farmlands. Very often the whole family moved out to these new areas and little colonies grew up—three Barrett houses out near Barrett’s Mill, five Wheelers at Nine Acre Corner, Buttricks beyond Punkatasset Hill, the Wrights beyond the Assabet.

If the first settler sold his house near the center it was often to a man who had a second source of income, a blacksmith, a weaver, a goldsmith, a potter, an innkeeper or a trader. All of these men also farmed for their own subsistence, and kept some cattle on the small acreage which went with the village house lots, but the special trades and skills began to turn Concord into a trading center where merchants could make a living exchanging imported sugar, rum, spices, and tea in return for native manufactures—furniture, cloth, leather goods, pottery and wooden ware—for the farm products—apples and cider, winter vegetables, squash, onions, beans, corn meal and wheat flour.

A farmer who raised all the food for his family, raised also his own help, made his own clothing of home grown wool or flax and needed only industry and economy for success. Those were the New England virtues along with the Sunday virtue of piety.

The houses now could be more elaborate, the downstairs rooms were paneled, the cooking went on in a lean-to (or linter) which ran all the way across the back of the house with a vast fireplace added to the original chimney. Sheds ran to the left or right to give shelter in getting out to the outhouse, to keep firewood under cover, to add extra rooms (shed-chambers) for extra sleeping rooms.

Very often one end of the lean-to was a small warm bedroom for the most favored members of the family, the grandparents, the uncles or aunts, or the mother with the new baby. Real estate agents always call these “borning rooms” but I doubt whether they were left idle in the months when no baby was due, and I doubt whether the average family even in those prolific days, had more than one baby per year. Actually in Concord, the population barely held its own during the first century. Poverty and disease kept it down. The Indian Wars, besides the families slaughtered, also had another result. It took the men all over New England where they saw other valleys and other rivers, which made them join the migrations to central and western Massachusetts, to southern Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont.

In the eighteen hundreds it was a different story. Those were the days of the big family and the days when houses had to grow.

The eighteenth century house, if new, had higher ceilings than before. Its salt-box roof sloped less sharply, so that there was more room upstairs. The upstairs rooms had fireplaces. Provision for a better cellar might be made by setting the first floor a little higher above the ground. Sometimes an old house was raised a couple of feet to give more head room. The projecting covered front entrance dates from this period.

Toward the close of the century a few square houses were built. The Wright Tavern was perhaps the first of these. The second story had four good bedrooms; the third story had perhaps as many as six to eight cheaper accommodations. Now the central chimney was replaced by two chimneys with a central hall between. Immediately, owners of old houses began taking down the big central chimney and building two smaller ones in its place. Soon these were placed on the outer wall. The next development was the four chimney house with all four chimneys on the outer walls. This led naturally to the brick ended houses where the outside chimneys became part of the sidewalls. These were much easier to build in the 1820s when the Middlesex Canal could bring up bricks by water form Medford.

This period coincided with the development of Main Street so that several such houses were built there.

As far as I know only two all brick houses were built—the Hepburn house on Lowell Road at Barrett Mill Road and the Hastings house in the center, which was torn down when Friend’s block was built on the corner of Walden Street. Up to this time every house was built by the owner for himself.

The coming of the railroad was the next stimulus to house building. On Hubbard Street, for the first time, houses were built by promoters for sale or rent to others. Belknap Street, Bedford Street, Thoreau Street, Main Street beyond Thoreau Street, Grant, Brooks, and Elsinore streets and Monument Street were developed by carpenters, merchants and bankers. The style of construction reflected the taste of the day, the development of the iron cooking stove, and furnace heat. Since houses were made to sell, they were kept simple. A good many were made by moving and remodeling old barns, old stores and old houses. No Yankee ever threw anything away; and in the days before running water and sewerage, before cellars and heating pipes, one could jack up almost any building and move it with oxen.

When I began to list and study old Concord houses twenty five years ago, I interviewed all of the old natives I could find and many were their tales of how this house once stood on Main Street or that house was moved from Monument Street. After the move the house usually became unrecognizable with Victorian trim, front piazzas, bay windows, or windows with large panes, and except for lingering memories its age was forgotten.