|

Introduction

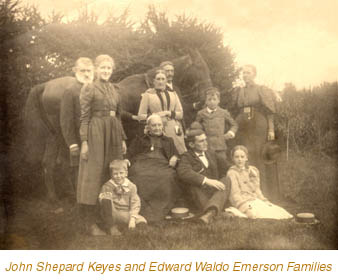

The 19th century photographic techniques and formats developed after the daguerreotype—the ambrotype, the tintype, the albumen paper print produced for carte de visite, cabinet card, and other use from collodion wet-plate glass negatives and eventually from gelatin dry-plate negatives—also enhance our perception of past lives. Even mass-produced carte de visite images of famous men and women in stock poses sometimes transcend the intense commercialization of photography to convey the distinctive personal qualities of the sitter. What, specifically, do 19th century photographic portraits tell us about their subjects? They suggest many things, some of them not so different from what sensitive modern portraits may reveal, some of them discernible only with the heightened perspective created by the passage of time. On the most obvious level, they show the accidents of personal appearance, beauty and homeliness alike, hinting at the degree to which countenance and figure may have affected the way other people responded to a sitter. They disclose personality traits and conditions of life, too—the negative (vanity, arrogance, weariness, poor health, and depression, for example) as well as the positive (alertness, generosity, spirituality, vitality, confidence, prosperity). Portraits of more than one sitter may convey emotion—married love or maternal tenderness—or its lack, or perhaps the inability of a subject to express deep feeling before an audience. A portrait also serves as a window into a particular moment in the sitter’s life—perhaps a peak of prosperity and well-being before a reversal of fortune or a decline of health, or a time of family happiness before the death of a loved one. Indeed, our retrospective knowledge of what life held for certain people after the shutter closed—knowledge to which the subject of a photograph was not privy—imparts a particular poignancy to many 19th century portraits. At a time when women frequently died in childbirth, when disease could not be effectively controlled, and when childhood mortality was high, portrait photographs often documented a tolerable present as a means of preventing its obliteration by an uncertain and possibly devastating future. Death portraits of babies and young children represent a belated attempt to hold on to a present that has, in fact, already passed. Group portraits sometimes illuminate the social support system and practical benefits provided by extended family life and reveal the degree to which the community was shaped and strengthened by blood ties. And collections of family portraits over several generations may demonstrate with startling clarity the persistence of particular physical and personality traits among kin. Finally, antique portraits show that in the 19th century, as now, social expectations to some extent dictated how a person of a particular age and a particular station should look and behave. Photographs occasionally captured the degree to which a sitter was unwilling to subordinate individuality to produce a desired result. Some children’s portraits, in particular, convey nothing so much as the young subject’s impatience with the requirement of holding a pose that conformed to idealized adult notions of childhood. Concordians in the 19th century were as eager for photographs of themselves as were Americans everywhere, in all regions of the country, in large cities and small towns alike. The extensive photographic archives in the William Munroe Special Collections of the Concord Free Public Library include rich holdings of 19th century portrait images of Concord people. These range in date from 1846 (the date of a spectacular daguerreotype of Frederic and Eliza Woodward Hudson; displayed as item 21 in the exhibition) to the turn of the 20th century (many gelatin dry-plate glass plate negative images by Concord photographers Alfred Munroe and Alfred Winslow Hosmer among the late-century examples). The library’s 19th century portrait holdings document a broad swath of Concord life, from the humble to the affluent. They include images by Concord photographers, by photographers based elsewhere, and by unidentified photographers as well (some of these possibly itinerant photographers for whom Concord was a stop). The library has acquired such images since its opening in 1873. Many have been added through gift, some through purchase. The library photographic collections—19th century portraiture included—constitute a growing and much-consulted resource, heavily used for research and publication purposes and still actively developed. “Captured by the Camera” offers a representative selection of expressive 19th century portrait photographs drawn entirely from the library collections. All displayed images are of people who lived some part of their lives in Concord, taken during or about the time of their residence here. Since the ability to research the subject of a portrait enhances the meaningful reading of the information that portrait conveys, all are of identified sitters. Although library holdings include many images of Concord’s famous 19th century authors, however, none have been used in the display. Many author images are familiar through previous publication in books and articles and therefore lack the impact of portraits that most viewers have not already seen. Moreover, this exhibition celebrates the full spectrum of 19th century Concord people, not just and not mainly its most prominent residents. Locally beloved though they are and will remain, Concord’s authors formed only a part—and arguably a relatively small part—of day-in, day-out Concord life. Their biographies reflect only a fragment of the town’s social history. On its own and in combination with other types of source material, each portrait in this display tells a unique personal story. Collectively, these stories shed light on both the evocative eloquence of photography as a documentary form and the common humanity that binds Concordians today to those who lived here in earlier periods. If you were viewing a specific numbered image when you clicked to this page, |

|

|

The daguerreotype became a popular portrait medium during the early to mid-1840s. From then on, Americans embraced photography as a means of capturing the defining qualities of a subject at a particular moment in time. The daguerreotype—each example unique, different even from others made at the same sitting—caught with candor and immediacy those fleeting expressions of personality and circumstance which the subject often revealed unconsciously. Modern viewers, accustomed to technically sophisticated photographic effects and enhancements, are nevertheless frequently moved by the intimate access to character and condition that these early portraits afford. Although we tend not to think of them primarily as such, these first photographic specimens are sources of biographical information. They complement letters, diaries, and other types of primary documentation, allowing us in the 21st century a better understanding of our predecessors and their lives.

The daguerreotype became a popular portrait medium during the early to mid-1840s. From then on, Americans embraced photography as a means of capturing the defining qualities of a subject at a particular moment in time. The daguerreotype—each example unique, different even from others made at the same sitting—caught with candor and immediacy those fleeting expressions of personality and circumstance which the subject often revealed unconsciously. Modern viewers, accustomed to technically sophisticated photographic effects and enhancements, are nevertheless frequently moved by the intimate access to character and condition that these early portraits afford. Although we tend not to think of them primarily as such, these first photographic specimens are sources of biographical information. They complement letters, diaries, and other types of primary documentation, allowing us in the 21st century a better understanding of our predecessors and their lives.