|

1851 ADDRESS IN

CONCORD ON THE FUGITIVE SLAVE LAW

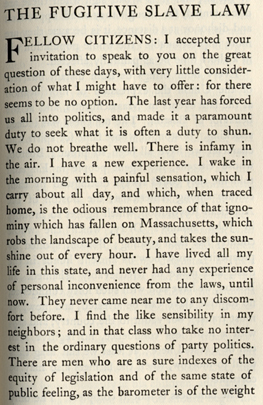

39. Ralph Waldo Emerson. “The Fugitive Slave

Law: Address to Citizens of Concord, 3 May, 1851,” pages [177]-214

in Miscellanies, Volume 11 of the Autograph Centenary Edition of

The Complete Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson (Cambridge: Printed at

the Riverside Press, 1904). Letterpress on paper; bound in green/brown

linen. Autograph Centenary Edition (12 volumes, 1903-1904): Myerson B19.

Purchased from the Town Fund, 1904. Copy number 332 of a limited

edition of 600 copies.

The addition of territory through war with Mexico (1846-1848) inflamed slavery/antislavery tensions, resulting in the Compromise of 1850, which was an attempt to delay impending national crisis. By the Compromise, California was admitted as a free state, the territories of New Mexico and Utah would decide the slavery question for themselves upon admission to the Union, the boundary between Texas and New Mexico was established, and the slave trade was abolished in Washington, D.C. The Compromise of 1850 also included the Fugitive Slave Law, which required the return of runaway slaves to their owners. Many Northerners were furious over and unwilling to obey the Fugitive Slave Law. Emerson was outraged by the Fugitive Slave Law and by early attempts to enforce it. His journal and letters after its passage were full of anger. He seethed, for example, in one entry in 1851, “And this filthy enactment was made in the 19th Century, by people who could read & write. I will not obey it, by God.” Edward Waldo Emerson wrote in Emerson in Concord of his father’s preoccupation with the detested law: “He woke in the mornings with a weight upon him … When his children told him that the subject given out for their next school composition was, The Building of a House, he said, ‘You must be sure to say that no house nowadays is perfect without having a nook where a fugitive slave can be safely hidden away.’ ” Edward recalled, too, that his father’s rage was channeled into legal research: “The national disgrace took Mr. Emerson’s mind from poetry and philosophy, and almost made him for a time a student of law and an advocate. He eagerly sought and welcomed all principles in law-books, or broad rulings of great jurists, that Right lay behind Statute to guide its application and that immoral laws are void.” On April 26, 1851, thirty-five of Emerson’s Concord townsmen signed a letter asking him publicly to present his views on the law. On May 3rd, he delivered an impassioned speech –his first of several in reaction to the Fugitive Slave Law. In the address, Emerson openly advocated breaking the law on the grounds that an immoral law carried no authority. (The year before, Henry Thoreau had offered a similar view in his “Resistance to Civil Government,” now known as “Civil Disobedience.”) The speech was well-received by the antislavery community. Although under normal circumstances not much inclined to political activism, Emerson repeated the speech a number of times in various Middlesex locations to support the campaign to elect Free Soil candidate John G. Palfrey to the United States Congress.

No image in this online display may be reproduced in any form, including electronic, without permission from the Curator of Special Collections of the Concord Free Public Library.

Next Entry - Previous Entry - Back to Section V Contents Listing - Back to Exhibition Introduction - Back to Exhibition Table of Contents |