|

THE CHEROKEE SITUATION,

1838

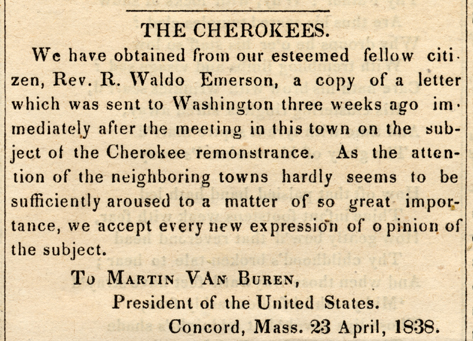

37. Ralph Waldo Emerson. “The Cherokees,” as printed

in the Yeoman’s Gazette (Concord), May 19, 1838; reprinted from

the Daily National Intelligencer (Washington), May 14, 1838. Intelligencer

version: Myerson E10. Letterpress on paper.

Government policy during the course of expansion westward was dedicated to uprooting Native Americans and to eradicating those among them who proved uncooperative. As treaties were signed and tribes relocated, some Americans spoke out. In 1838, the federal government prepared to employ soldiers to remove unwilling Cherokees from Georgia and Tennessee to Oklahoma, in accordance with the questionably negotiated 1835 Treaty of Echota. On April 19, Emerson wrote in his journal, “Then is this disaster of Cherokees brought to me by a sad friend to blacken my days & nights. I can do nothing. Why shriek? Why strike ineffectual blows?” As with antislavery, Emerson took up the cause of the Cherokees reluctantly. On April 22nd, a meeting was held in the First Parish in Concord in protest of government policy and action. Emerson and Squire Sam Hoar—Elizabeth’s father—were among the speakers. Emerson also helped to formulate a resolution to send to Washington, and was persuaded to write a letter to President Van Buren. Dated April 23rd, the letter was published in the Washington Daily National Intelligencer for May 14, 1838, reprinted in Concord in the Yeoman’s Gazette for May 19th, and in June in the Christian Register, the Old Colony Memorial, and the Liberator. Emerson’s journal makes perfectly clear how much writing the letter conflicted him. The day after the protest meeting, he wrote: “This tragic Cherokee business which we stirred at a meeting in the church yesterday will look to me degrading & injurious do what I can. It is like dead cats around one’s neck. It is like School Committees & Sunday School classes and Teachers’ meetings & the Warren street chapel & all the other holy hurrahs. I stir in it for the sad reason that no other mortal will move & if I do not, why it is left undone.” And again, on April 26th, he vented his distaste for “stirring in the philanthropic mud”: “I fully sympathise, be sure, with the sentiment I write, but I accept it rather from my friends than dictate it. It is not my impulse to say it & therefore my genius deserts me … Bah!” Despite Emerson’s reservations, his letter was strong and clear. As he had expected, however, it did not alter the course of events. It is not even certain that Van Buren actually read it. Nevertheless, as he later would in relation to antislavery, Emerson had shown a willingness to transcend his personal reticence about reform in response to social wrong.

No image in this online display may be reproduced in any form, including electronic, without permission from the Curator of Special Collections of the Concord Free Public Library.

Next Entry - Back to Section V Contents Listing - Back to Exhibition Introduction - Back to Exhibition Table of Contents |