|

NATURE, 1836

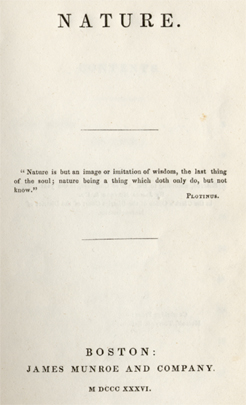

23. Ralph Waldo Emerson. Nature (Boston:

James Munroe and Company, 1836). Letterpress on paper; bound in green

cloth. Myerson A3.1.a (second state; binding Cloth 7, Stamping B).

From the Emerson collection of William Taylor Newton, presented by Edith

Emerrson Forbes and Edward Waldo Emerson, 1918.

Emerson had begun to think about the book that would eventually be published under the title Nature as early as 1833. After he moved to Concord in 1834, he worked on it while boarding at the Manse and then in the Coolidge house. In preparing it, he drew on material from his journals, sermons, and lectures. On June 28, 1836, he wrote to his brother William, “My little book is nearly done.” Nature—a lengthy essay divided into chapters—was published in September of that year. At the beginning of Nature, Emerson posed the questions, “The foregoing generations beheld God and nature face to face; we, through their eyes. Why should not we also enjoy an original relation to the universe? Why should not we have a poetry and philosophy of insight and not of tradition, and a religion by revelation to us, and not the history of theirs?” For Emerson, the presence of the divine spirit in both nature and the human soul made a direct understanding of God and openness to the natural world key to the understanding of broader truth. In each manifestation of God, man could discover in encapsulated form all universal laws at work. What was required for such perception was neither the received dogma of traditional systems of belief nor reasoned logic, but rather a more mystical intuition capable of revealing truth and morality in the various expressions of the divine. Slim volume though it was, Nature drew response from reviewers. Orestes Brownson wrote about it for the Boston Reformer, for example, the conservative Francis Bowen (a critic of Transcendentalism) for the Christian Examiner, Samuel Osgood for the Western Messenger, and Elizabeth Peabody for the United States Magazine and Democratic Review. The book generated mixed reactions. Even those reviewers sympathetic to Transcendental thought found aspects of Emerson’s presentation radical, unsettling, and unconvincing. Peabody—in many ways the consummate Transcendentalist—urged Emerson in her favorable review to write another book to clarify the philosophy that the reader could only understand “by glimpses” in Nature, and to expand upon certain of his religious ideas.

No image in this online display may be reproduced in any form, including electronic, without permission from the Curator of Special Collections of the Concord Free Public Library.

Next Entry - Back to Section IV Contents Listing - Back to Exhibition Introduction - Back to Exhibition Table of Contents |