VIII. CIVIL WAR

The Civil War began on April 12, 1861, when Confederate forces attacked Fort Sumter. Before Abraham Lincoln's election to the presidency in 1860, many northern abolitionists distrusted the Republican candidate's feelings about antislavery. In July of 1860, members of the Middlesex County Antislavery Society resolved that Lincoln—then still a candidate—was "a declared advocate of every pro-slavery compromise in the Constitution ever claimed by Calhoun or endorsed by Webster." After Lincoln took office, much of the antislavery community was uncertain or critical of his motivation and effectiveness in conducting the war, which was initially framed as the means of preserving the Union, and only later officially linked to ending slavery.

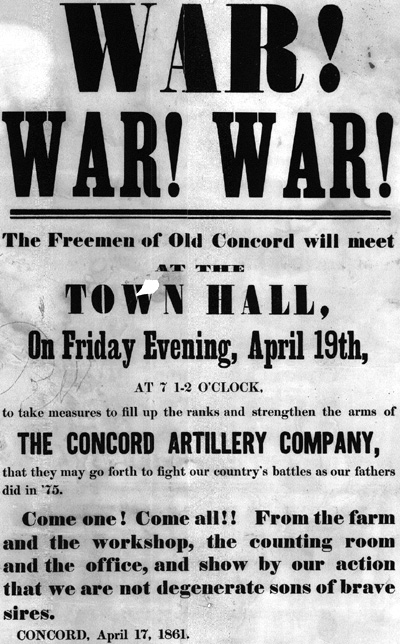

Lidian Emerson's feelings on the war reflected those of many abolitionists. She welcomed it, and yet could not fully support it without emancipation as its justification. Her daughter Ellen wrote in her biography of her mother: "In 1861 when the war broke out Mother felt nothing but gladness. 'This is the beginning of the end of slavery,' was the first word she said to me Edward was then seventeen. He hoped at eighteen to go to the war, but Mother always said 'not till the slaves are freed.'" In writing her daughter Edith in April of 1861, at the outbreak of the war, Mrs. Emerson connected Concord's battle for liberty in 1775 with the prospect of emancipation: "Is it not a wonderful and most auspicious omen that our Soldiers went forth to fight for liberty and right on the Nineteenth of April. It means something, be sure. Oh what an exciting day! The bells & guns the cloudy day and the brilliant sunset the departure the enthusiastic meeting in the evening. There has not been such a day for 86 years." In 1863, when emancipation finally came, she wrote, "[T]he Stars and Stripes were on the Flag of a nation at war against the dearest and most sacred rights of Humanity; a nation to which I was sad to belong. I could not love but must hate such a Country. Now I begin to feel that I may love the Country and its Flag—it will before long be the sign of Freedom for all. 'Union' is comparatively dust in the balance."

Similarly, Ralph Waldo Emerson was unable to express wholehearted approval of the president until Lincoln committed himself to emancipation. But he won Emerson over with his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation of September 22, 1862. From this point on, Emerson—who devoted considerable thought to the subject of great men—respected Lincoln's greatness. On October 12, 1862, he delivered an address on the Emancipation Proclamation—which he regarded as a "poetic act and record," an act "of great scope," and one of the "moments of expansion in modern history"—at the Music Hall in Boston. The address was published in the Atlantic Monthly for November, 1862.

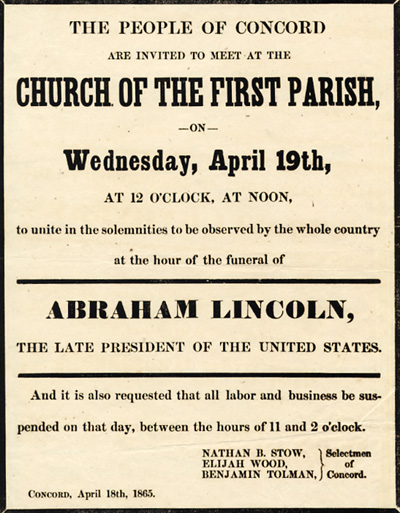

Lincoln was shot by John Wilkes Booth on April 14, 1865, a few days after the Civil War came to an end, and died the following morning. On April 19th (as Lidian Emerson had observed, a highly symbolic day for Concord), the town halted the business of ordinary life for three hours and held a funeral service for the slain president at the First Parish. The order of services included an address by Emerson, who emphasized Lincoln's particular fitness to the difficult role he had assumed: "This man grew according to the need. His mind mastered the problem of the day; and, as the problem grew, so did his comprehension of it. Rarely was man so fitted to the event." In his address, Emerson likened the power of Lincoln's address at Gettysburg to that of speeches by John Brown and Hungarian statesman and patriot Lajos Kossuth.

Henry Thoreau did not live long enough to witness emancipation or to judge Lincoln's performance throughout the war. He died on May 6, 1862.

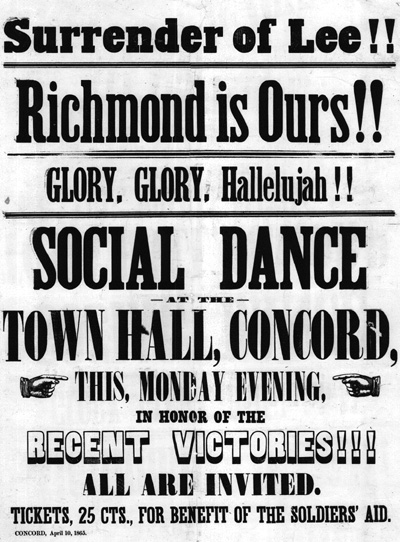

Despite their initial concerns, when war broke out antislavery reformers in Concord, as elsewhere, channeled their energies into concerted town-wide support of Union soldiers. Members of the Concord Soldiers' Aid Society sewed and packed boxes of clothing, bandages, food, and other items for the comfort and entertainment of the troops, and raised funds through dues, donations, collections at local churches, and benefits. Formed in 1861 to supply the needs of soldiers in the Concord Artillery, Company A, Fifth Regiment Infantry, Third Brigade, by 1862 the society provided boxes for all troops served by the United States Sanitary Commission. Well-attended meetings were held in the Town Hall and the First Parish vestry, later in the engine house near the train depot. Members—men as well as women—included Mary Merrick Brooks, Lidian Emerson and her daughters Ellen and Edith, Ann Bigelow, Colonel William Whiting and his family (daughters Anna Maria Whiting and Louisa Jane Whiting Barker and son-in-law Stephen Barker), Abba Alcott, Dr. Josiah Bartlett, Simon and Ann Brown, Elizabeth Hoar and her sister-in-law Caroline Brooks Hoar (Mrs. E. R.), Martha Prescott Keyes (Mrs. J. .) and her daughters Annie and Florence, Mary Peabody Mann, the Reverend Grindall Reynolds of the First Parish and his wife Lucy, Elizabeth Ripley, Frank Sanborn and his new wife Louisa, and Anne Damon (wife of Edward Carver Damon—whose mill in what is now known as West Concord turned out cloth for Union uniforms—and niece of Ann Bigelow of Shadrach fame).

During and after the war, some focused on the needs of the southern black population. Freedmen's aid societies sent money, clothing, and books for freed blacks, and funded northern teachers willing to undertake the education of former slaves. In Concord, George Brooks—son of Mary Merrick Brooks—was president of the Concord Freedmen's Aid Society. Harriet Buttrick, Jane Hosmer (a daughter of farmer Edmund Hosmer), and Angelina and Elizabeth Ball all taught freed blacks in the south.

Nearly fifty men closely connected with Concord died in the Civil War—a significant, deeply felt local loss. Sobering and painful though the military struggle was for the country and for individual towns in both north and south, the war fulfilled the stubbornly pursued hope of abolitionists whose persistent activism from the 1830s on had collectively influenced the course of national events.

Yet even the most fervent of Concord abolitionists understood that emancipation and Union victory comprised only the first step toward social justice. Late in 1865, Mary Merrick Brooks wrote Wendell Phillips (her long-time friend and comrade in the antislavery struggle), "The work of Abolitionists is not done, and will not be, until all God given rights are granted to the so called freedmen."

93. Abraham Lincoln. Nineteenth-century facsimile of letter to "Madam" [Mary Peabody Mann], Washington, April 5, 1864, on Executive Mansion letterhead. From Concord Free Public Library Letter File, CFPL Vault Collection.

|

|---|