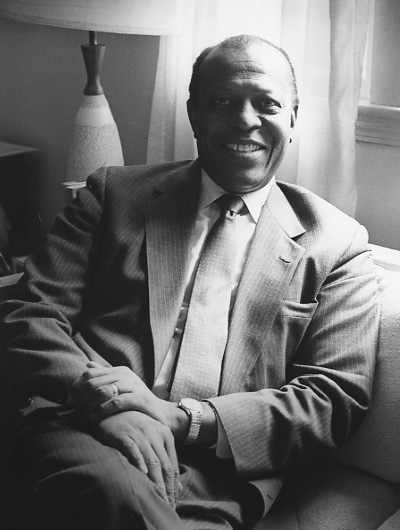

Dr. Charles Willie

41 Hillcrest Road

Age 62

Interviewed March 23, 1989

Concord Oral History Program

Renee Garrelick, Interviewer.

Segregated Dallas childhood

Segregated Dallas childhood

Father as Pullman Porter

Mother's influence on education

Spirituals and religion

At Morehouse College, Ga., fellow student with Martin Luther King

Influence of Martin Luther King and Montgomery bus boycott

Comment on national black leadership

Stand against discrimination of women clergy in Episcopal Church

As consultant for school desegregation in

Boston Public Schools

Court appointed master under Judge Arthur Garrity

Appointment by Mayor Raymond Flynn, program of controlled choice

1978 METCO racial disturbance at Concord-Carlisle Regional High School

resulting in formation of Concord-Carlisle Human Rights Council

I grew up in Dallas, Texas, before 1954, which was the year

in which the Supreme Court gave the Brown opinion which outlawed

segregation in most institutions in our society despite the fact

that it continued for many years past that ruling. So I experienced segregation as a youngster in Dallas. I am an urban

sociologist and like to understand the cities, and I have studied

most of the cities in which I have lived including Boston and

Syracuse, but I didn't know very much about Dallas because my

movement in Dallas was in segregated corridors. There were black

neighborhoods and white neighborhoods, and blacks seldom entered

white neighborhoods. There were common shopping centers in

downtown Dallas, but even in those days department stores had

separate toilets for blacks and whites and separate drinking

fountains for blacks and whites, and the opportunity to try on

clothing especially for black women was not a possibility in the

I grew up then in the black community in a sector of

Oakcliff, which was the western part of Dallas which had some

paved streets, but also many dirt roads that were unpaved in an

all-black community, and I went to segregated schools. The

elementary school was about a block and a half from where I lived,

but the high school was in the south part of Dallas, and we had to

use buses to go from the western sector of Dallas in Oakcliff to

the south part of Dallas. Incidentally, in those days, although

we had to bypass high schools that were located in Oakcliff in the

western sector, we nevertheless had to pay our own bus fare to go

to south Dallas to go to high school. I went to Lincoln High

School in south Dallas and graduated from there in 1944. I also

grew up during the period when blacks had to sit at the back of the bus and at the back of the streetcar. It was always humiliating to me to pay one's fare and then have to push through a

crowded streetcar all the way to the back of it, but these were

the experiences that one grew up with. I was born in 1927, and of

course the great depression came in the 1930's, so my childhood

was during the period of the great depression.

My father worked for the Pullman Company for 42 years until

he retired. He was from the rural area of Texas. He grew up on

the farm in Panola County in a little community called Deberry in

a relatively large family, and his parents were without much

education at all, although his mother was a person of some

interest and foresight, and she died relatively young in life

around age 40, 45. My father recalls that before her death she

asked him if he and one or two of his other brothers would be

responsible for the education of their sister, who was the

youngest child in the family. My father took that request from

his mother and his response to it very seriously and left the

family home in the rural area of Texas to go to Ft. Worth, Texas,

one of the cities in Texas, to earn a living, and he got a job

with the Pullman Company and later was transferred to Dallas. The

Pullman Company was a relatively decent job. It was a service

job. The income from it wasn't that much, but there were tips

which porters received for shining the shoes of their passengers

and making them quite comfortable, and the job with Pullman

Company was a relatively secure one because Philip A. Randolph

organized the Pullman porters. It was one of the first labor

unions consisting only of black individuals, and while that union

did not enable my father and his associates to receive more

income, it did give them job security so that they could not be

fired in an arbitrary and capricious way simply because a passenger may not like the way that the porter looked. I make that

point because I am sure that I would not be here today as a

professor at Harvard University and with the Doctorate degree in

sociology from Syracuse University if my father had not been able to maintain continuous employment. We bought three homes at

least, traded in one and moved up to a larger one as the family

increased, and we would not have been able to do that had he not

had continuous employment. I remember going to the mortgage

company that financed our home during the great depression and

paying as much as $10 a month on the mortgage. This was not a

large amount, and of course mortgages in those days were not

great, but the fact that the payment was regular, continuous meant

that the mortgage company never foreclosed. So we never had the

problems of starts and stops that some families had even though we

were relatively without much income. I always say in our

household there was bread enough but not much to spare.

Now my mother was a college graduate. She also grew up in

Marshall, Texas, which was in the eastern part of Texas like

Deberry. Marshall was a little larger community, and it was the

trading center where people from the rural areas like Deberry came

to purchase goods and to sell the products from the farm, and my

father met my mother in Marshall when he was attending a Sunday

School convention. They both were officers of that convention and

sat together and got to know each other, and over the years they

became engaged and married. My mother's father was a blacksmith.

He was born in slavery as was my grandfather on my father's side,

so I have grandparents who were born before slavery ended in the

United States, and the trade that my mother's father learned was

that of a blacksmith, which he continued after slavery, and that

was the means whereby he supported their family. In Marshall,

Texas, there is a small college named Wiley College, and in those

days blacksmiths were used to help erect buildings. They didn't

have steel beams running through multi-story buildings, but they

did use anchor irons that help support the structure of the

building, which was fashioned by blacksmiths, and my grandfather

helped erect a building on the campus of Wiley College in

Marshall, Texas, which was a black school, but the school was

unable to pay him all that was due him, and he therefore requested

the residual to be placed in a tuition account for his daughter. My mother was the youngest in that family. Her family name was

Sykes, and she was the youngest of the Sykes' daughters, and as a

result of the school being unable to pay my grandfather all that

was due him, she went to school. This was very interesting

because my grandfather could figure, as they said in those days,

but he could not read, so that payment of my grandfather by

reserving funds in a tuition account, in other words the payment

in kind, enabled my mother to go to college, and she graduated

from Wiley in 1921 when I think she was close to about 29 years of

age, and she and my father married and moved to Ft. Worth to set

up housekeeping.

I mention that because a woman who was born before the turn

of the century as my mother was, and incidentally this is 1989 and

she is still alive and is 98 years of age, one born before the

turn of the century seldom had a college education, but she did.

She did not work outside of the home, although life was certainly

severe inside caring for five offsprings with little income, so I

never say that she didn't work, but she didn't work outside of the

home. She took care of us during the days when there were nothing

such as washing machines, vacuum cleaners and central heating. I

mention this because the only job that she could get, and we did

need the funds, would have been at teaching school, but during the

great depression in most city school systems women could not be

hired if their husbands had a job, and my father was a Pullman

porter; therefore, the Dallas school system would not hire my

mother as a school teacher. This means that during the age of

segregation and discrimmination the only job available to her as a

black woman would have been that of a maid in a private household

of a white family, and my parents did not think that was

appropriate for my mother to be a maid in the private household of

a white family.

Therefore, my mother said that she and her husband decided

that she would stay at home and have a school at home for her

husband and for her children. I advisedly state for her husband because my father only finished the eighth grade; and she did. We

did not recognize the significance of that decision, but all of us

as we went to elementary school knew our alphabets and rudimentary

ways of calculating. She was a person of great wisdom, had a

sense of art and music, although she couldn't play any of those

instruments, but had an appreciation of language and poetry. She

was our tutor, and she was a tutor for her husband, and I think

the accomplishments of her offspring are indicators of the great

job that she did. She made sure that there was healthcare. Of

course we didn't have funds to obtain it, but if there were free

health clinics anyplace in the community she found those.

They stayed in close contact with the schools. They had good

relationships in the community. My father was a respected member

of the community because he had regular work and also because he

was an officer of the church, and she was a member of the church

and we all grew up in the church. So we all had institutional

supports in the community that came our way, first because there

was regular employment for my father and also because my mother

put to great use within the family the education that she had

nurtured all of us. As a result, my family of orientation as the

sociologist would say, that is the family into which I was born,

consisted of five children, and all five of those children

graduated from college, all five obtained some graduate education,

four with masters degrees, and two with doctorate degrees. This

was unusual because, as I said, it was a working-class family and

there were not many resources, and as a result I think that

accomplishment came about because of the unique qualities and

contributions which my mother made that was in 1973. I always

identify that year as being three years before "Roots," by Alex

Haley, was published that I took tape recorder in hand and went to

Dallas from Syracuse, New York, where I was working as a professor

and administrator at that university to interview my parents.

Both my father and my mother were still alive in 1973 to find out

how they did it, and from that interview I discovered that my

mother had had a tremendous impact upon our family, although the community probably had given more credit to my father than to my

mother because he was a very stable worker and took care of his

family. He made great sacrifices for them, but I understood that

it was my mother who probably was the mainstay and that really was

the person who we had to give a great deal of credit to for the

achievement of the offspring and for the achievement of my father

and her husband.

I grew up as a youngster singing in my church choir, and

spirituals were staples of the repertoire of that group, and then

in high school I learned to play a trumpet, but I also sang in the

high school choir. It was called the Harry T. Burleigh Choir.

Harry T. Burleigh was a famous black composer, and then when I

went to college, Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia, which

incidentally is the same college from which Martin Luther King,

Jr. graduated, we by accident were classmates from 1944 to '48.

At Morehouse College I played in the football band and also sang

in the glee club which toured the country from time to time.

During the war years we didn't do much touring, so I went as far

as St. Louis from Atlanta, Georgia, but all of this musical

background was a very interesting experience for me. Indeed,

during high school I played in football band and in jazz

orchestras and for two years that was the way I earned my spending

money in high school playing in a jazz band on Saturday night at a

dance hall. My high school teacher was in charge of the dance

band, so my parents let me play in it because they knew that he

wouldn't permit us to indulge in alcoholic beverages and that he

would look out for us, and that was the kind of relationship, an

extended family relationship all the way from home, school, and in

the community. Well, I grew up then surrounded by music, playing

it as well as singing it and therefore the spirituals became an

important part of my knowledge base, and I have analyzed them over

the years. One day I am going to write an essay on spirituals and

the sociology of knowledge because I think the spirituals have

enabled people to endure, to cope, and to transcend, and this has

been one of the beautiful aspects about one's history as a racial minority. It is not a history and it is not a background that one

is ashamed of, and it is not a history or a background that is

full of pain. Yes, there was suffering, but then there were tools

for coping with the suffering, and the spirituals that I grew up

singing were not only entertainment, they were in my judgment

indications of what one ought to do to cope with the hardships

that one faced. The spirituals have a theme running through them

of humility. One is never raised to be puffed up. The spirituals

have running through them a theme of transcendence. The spirituals have running through them a theme of justice, so I commend

them to the American public as being basic folk songs from this

society that more people ought to know about and really ought to

sing and participate in than just black people. I think the

spirituals belong to this entire nation, and unfortunately the

nation has not recognized them and has not really studied and

pondered them enough to really let their secret and wisdom be

revealed.

The spiritual about, "Go down Moses way down in Egypt land,

tell old Pharaoh to let my people go," that is a song of hope.

"When Israel was in Egypt land, let my people go. oppressed so

hard they could not stand, let my people go. Go down Moses, way

down in Egypt's land. Tell old Pharaoh to let my people go." It

is an interesting spiritual. Despite the fact of slavery, despite

the fact of oppression, there is the hope that some way, some day

people are going to be released from it. Then there are other

kinds of spirituals, such as one I like because I think it

indicates kind of the humility that is part of the black experience, "Keep a inching along, inching along. Jesus is coming by

and by. Keep a inching along like a poor inchworm. Jesus is

coming by and by." Now to call oneself a poor inchworm is a very

important concept, but despite the fact that one may be a poor

inchworm, one is also admonished to keep a inching along. Well,

spirituals are like those and others "In that great getting up

morning, fare thee well, fare thee well, in that great getting up

morning, fare thee well." That's telling one that something is going to happen that's important someday despite what's happening

today that is not so important. Or if I had time I could quote to

you spiritual after spiritual I have sung over the years, and as I

say one day I am going to do an essay on the spiritual and the

sociology of knowledge because I think that it is very important

for American culture to be aware of this if it's anchored in this

kind of a music form.

I include that in some of my speeches: "It's me, it's me,

it's me oh Lord, standing in the need of prayer. It's me, it's

me, it's me oh Lord, standing in the need of prayer. Not my

brother, not my sister, but it's me oh Lord, standing in the need

of prayer. Not my brother, not my sister, but it's me oh Lord,

standing in the need of prayer." This is a very important song.

It doesn't try to attribute one's problems to others. It

attributes to oneself, "I am standing in the need of prayer," but

also when one is prayed for, one is prayed for by others, and so

it connotes an understanding of the community as the support

system, and the community both prays for one for one's deliverance

and the individual admits that one is in need of deliverance. It

is not the self-centeredness. It is not the self-reliant orientation that I think has been probably one of the great impediments

in our society. Certainly self-reliance and self-sufficiency give

rise to a feeling of arrogance and a feeling of pride, and of

course we know that pride is the great sin that makes it difficult

for people to rely upon others and to receive their help. So

these and other kinds of themes I think have been very important

in my own lifestyle despite the number of different experiences I

have had in different sectors of the country and in different

institutions. I always remember these ideas and themes that came

from my childhood.

I was baptized in a church called Elizabeth Chapel CME

Church. CME are initials for colored, Methodist, Episcopal

church, so the church in which I was baptized was Elizabeth Chapel

Colored Methodist Episcopal Church. Later they changed the name to Christian Methodist Episcopal Church, but there are several

branches of Methodist Church there. There is the AME Church, the

African Methodist Episcopal Church, and there is the AME Zion

Church, which is the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, and

then there is the CME Church, the Christian Methodist Episcopal

Church, which as I say when I was growing up was called the

Colored Methodist Episcopal Church. Of course there are Baptist

churches, Pentecostal churches, and many other branches of

Christian churches found in black communities, but that is the one

that I grew up in, and I think it had a very important impact upon

me. You know morality and ethics and justice are very important

components of the lives of blacks. Joseph Fletcher, a social

ethicist, who used to be a faculty member of the Episcopal

Divinity School in Cambridge, once said that the boss principle in

life is love, and justice is love in action, and I would say that

justice has been an important component of the life of blacks and

the capacity to seek justice and to insist on it is an ethical

principle that is anchored in their church life, and I certainly

think this was true of Martin Luther King, Jr., who grew up in a

black Baptist church, and it certainly has been an important part

of my experience growing up in the Methodist church. After

leaving Dallas and journeying to Atlanta to go to Morehouse

College and then to Atlanta University, from which I received a

master's degree, I then came on to Syracuse, New York, to study

for my doctorate degree and I stayed there 25 years as a faculty

member and as a vice-president of Syracuse University after I

received my degree, but despite these experiences that whole

concept of seeking justice that comes out of one's roots in the

black church has been a very important part of my career, and I am

very thankful of that history.

We had marvelous teachers at Morehouse College, and we had

chapel each morning for about thirty minutes, and both our faculty

members, the president of the college, and visitors to Atlanta

always addressed us in chapel, and one of the important themes of

most of the addresses were that you may live in a segregated society but never have a segregated mind. We were free, and many

people did not realize how free we were in our own minds, but not

only that we could be free because we had had a range of associations, and most people don't realize that black colleges which had

black student bodies also had a substantial proportion of whites

on their faculties. At the time I attended Morehouse, I am sure

that one-fourth to one-third of the faculty was white, which meant

that I had a multi-racial and multi-cultural experience, actually

experience that most of the whites who attended school at that

time did not have. On white college campuses there were no blacks

to be found either in the student body or in the faculty. So this

broad base of multi-culture, multi-racial experience was one

factor that undergirded my understanding of my sense of myself as

someone significant, but the teachings of our teachers and our

administrators again helped us to understand our sense of

significance. Benjamin Elijah Mays was one of the nation's great

educators, and he was president of Morehouse during the time that

I was there, and he lectured in chapel each Tuesday morning. He

had a tremendous impact upon the student body, and I guess we have

to attribute to him as much as to anyone else the belief that we

had in ourselves as someone who could do a good job, who could

transcend, and who never permitted ourselves to be completely

defined by others. We always believed that we had to affirm

ourselves while others also confirmed us, but we knew that the

South was a function of affirmation and confirmation, and we

believed in ourselves, and we believed that we could transcend,

and we believed that we could do just about everything we wanted

to. Consequently, when I got to Syracuse University, although

there was some residual discrimination there, it did not phase me

because I had a sense of myself, and the sense of myself had come

out of my black college experience. Morehouse College in that

respect was a very wonderful experience for me, and I am very

pleased that I chose to go to it for my undergraduate education.

Eugene Talmadge in particular had a very negative opinion

about blacks. As you know, all citizens of the nation have the privilege of voting in federal elections, but the Democratic and

Republican parties were in the 1940's thought of as private clubs

as it were, and they retained the right to permit whomever they

wished to vote in the elections of their clubs. Now, of course,

the candidates who ran at the national level for federal offices

came out of these primaries, but in the 1940's blacks and other

minorities were not privileged to vote in the primaries where the

candidates were selected. I went to the Georgia state house when

that proposal to abolish the white primaries was being debated,

and the most interesting thing I remember is that I was put out of

the gallery. I couldn't even listen to the debate, and that

indicated to me how unfair was segregation and discrimination, but

what made us all feel good is they had to put us out. There was a

certain amount of chutspah, a certain amount of courage that

enabled us to place ourselves at risk to see to it that justice

was done. Nevertheless, we also did some other things on our own

that were not so courageous. Theaters did not permit blacks to

sit on the main floor. If there were three balconies, blacks

would be housed in the third balcony for performances and even

movies. And I recall our president ridiculing us for taking a

backdoor step to go up to the roof, we used to call it the buzzard

roost of local theaters just to see first-run films, and while

most of my colleagues and I would do it, we always felt guilty

when we did it because we knew we would hear a speech probably

Tuesday when the president addressed the student body ridiculing

people who would do that. And so we had these contending forces,

the force on the one hand to simply accept segregation and some of

the meager enjoyments that one could eke out of it personally,

such as sitting up in the buzzard's roost to see a first-run movie

and at the same time we had a contending force of an administrator

at one's college telling one that's wrong. That kind of conflict

set up in us is very helpful, I think, because it never enabled us

to accept oppression without having to think about why were we

accepting it and also without thinking it was our responsibility

to overcome it.

Many people have made funny statements about race relations

in the north and race relations in the south, and my attempt to

try to understand the different conclusions about race relations

in these two sectors of the country led me to engage in some

asserts that finally resulted in my principle about the critical

mass. It sometimes has been said jokingly that in the south

whites do not care how close you get to them so far as you don't

get too big, and in the north whites don't care how big you get,

that is in terms of reputation, esteem, and prestige, so long as

you don't get too close. These seem to be funny ways to describe

race relations, but I sort of felt that they really confuse the

whole issue. I found that neither of those ideas really made any

sense, and I was trying to in my own mind as a sociologist account

for the fact that the civil rights movement started in the south

but it has continued in the north, and it seemed to me based upon

my research that the civil rights movement started in the south

because there was a critical mass. You know in the United States

blacks used to be about one-fifth of the population back in 1820

and this was during the age of slavery. Now it's about one-tenth

or one-twelfth. But even though it was twenty percent of the

population in the 1820's, nothing happened. Blacks were enslaved.

One reason why nothing happened was because most blacks were

slaves. There were few blacks in those days but not many, and of

course, there were laws against educating blacks. There was no

differentiation in the black population. So it seemed to me that

in order to have real movement for liberation one had to have

first a critical mass, a population large enough to have an impact

upon the society at large, but then that population had to be

sufficiently differentiated so that some people were available who

could plan for the liberation movement, and that is precisely what

happened in Montgomery during the bus boycott that started in 1955

which Martin Luther King, Jr., led. The bus boycott was designed

to overcome segregated seating in the Montgomery buses, and

Montgomery had a large black population at least the population

substantially larger than one-fifth of that city, but it also had

a differentiated population. It had people who were college graduates, such as Martin Luther King., Jr., who had a doctorate,

it had lawyers such as Attorney Gray and others. These were

people who had sufficient knowledge and sufficient time to plan

for overcoming discrimination, and it had people of courage, such

as the maids and the other workmen who were willing to boycott the

buses and walk to work. The critical mass had an impact upon the

income of the bus company when there was a boycott, but the bus

company would have won eventually because that boycott could not

have lasted more than a year. People were getting tired. They

had to have some way of going to work. Just as they were about to

grow weary and the bus company about to win, the Supreme Court

ruled the segregated seating on public buses, common carriers, was

unconstitutional. That told me that that bus boycott in

Montgomery, Alabama, was won on one hand because there were

people, plain people, who were willing to both risk the loss of

job and experience inconvenience to walk to work, or to hitchhike

to work, or to get to work whatever way they could without using

the public transportation that discriminated against them, but it

also was won because there were people who knew how to go into the

courts, file a suit, and nurture that suit all the way to the

Supreme Court, and therefore get segregated seating illegal. It

took those two kinds of experiences.

Now in the northern sector of the United States there was

always differentiation of the population and a substantial number

of people who were middle class and who did have professional

roles and who could do the kinds of things that Dr. King and

Attorney Gray did in the south, but their numbers were always so

small that, even though they had the know-how of what to do, they

could not have an impact upon the community. So what one had in

years gone by is a differentiated population in the north of

blacks that was too small, and you had a large population in the

south that was undifferentiated, and the civil rights movement and

the haste that it made came about once one had both a critical

mass large enough, what I sometimes call sub-dominate population,

but also differentiated into different class levels so that there were people who could perform different functions. Once you had

both the critical mass and the differentiation, then the movement

took off, and that was very important.

As boys together there was no indication that Martin Luther

King, Jr., would rise to the heights that he did. He was a good

student, a serious student. We were taught at Morehouse College

never to accept authority because it was authority. We not only

listened to our college president, but we debated him. As a

matter of fact Benjamin May said that sometimes Martin Luther

King, Jr., would follow him from chapel all the way back to his

office in the administration building debating a point with him.

And we did this with our teachers too. Our teachers were always

alert because if they made a mistake, we would debate them as

students. This was part of the teaching that we learned, never to

accept authority because it is authority. Well, Martin Luther

King, Jr., at Morehouse was a very fine student, but he lived at

home. We called the students who lived at home city students as

opposed to campus students, and because he lived at home while

attending school he therefore was not able to become an important

part of campus politics, which was also part of our education,

part of our extra-curricular education. So, while he was a good

student and was serious and was concerned about issues, he also

was a student who enjoyed a good party, and he dressed in a flashy

way like the rest of us in those days. We had wide brimmed hats

called big-apple hats, and our pants were tapered down, so that

when they reached the ankle they were sort of, we called them

peg-top pants. He wore those garish costumes the way the rest of

us did. That's what teenagers do. But as he moved on through

life with the support of a warm family and continued his education

he began to see a mission in life, and the mission took him back

to the south after he left Boston University where he received his

doctorate degree in religion and philosophy, back to Montgomery.

Being one of the newest persons in town he simply had no enemies.

He hadn't had opportunity to have fights and fusses with the other

members in the black community, and when the bus boycott was declared, the persons declared that he be leader because he had no

excess baggage. He had no enemies. I usually describe his

ascendancy as being a person in a unique place at a unique time

who said yes. It was always wonderful for those of us who were

his classmates though because we were at Morehouse during the time

when World War II was in progress. The only reason we were there

is we were pre- draft age, I was 16 and he was 15 when we came to

school as freshmen, and the school only had about 300 or 400

students, so we all got to know each other very well. Morehouse

being a men's school would have closed if they hadn't recruited

youngsters like us who were pre-draft age. And because the

student body was so small we got to know each other very well, and

one of the enjoyable experiences as Martin Luther King, Jr.,

ascended to heights of being in effect a number one citizen in

this nation. He always made it possible for those who knew him

before he was famous to have access to him, and that was one of

the kind of special things that I recall of him having gone to

school with him, he always really let us have access to him even

though his time was very limited and he was called to assume a

number of responsibilities as his fame increased.

On the wall in my study there is a photograph of him with me

at Syracuse University. I met him several times at the Episcopal

Church's general convention where he spoke, and I have several

letters in my file that came from him, and of course one of our

children carries the name Martin which is in honor of Martin King

and Martin Buber. I recall going to Atlanta to lecture at

Morehouse College when Martin our middle child was born, and Daddy

King and Mrs. King were still alive, Martin's parents, were at the

banquet where I lectured, and we took them in to see Martin the

namesake. So we kept in contact over the years, and it was one of

those unique experiences that isn't repeated often, but I am very

thankful that it came my way.

I think that Jesse Jackson's accomplishments during the

presidential campaign is a direct outcome of the legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr. One must remember that Andrew Young, who has

served as the mayor of Atlanta, Georgia, was a Martin Luther

King., Jr., lieutenant. There are others spread around the

country, Wyatt T. Walker, an outstanding clergy person in New York

City, numerous individuals who worked with Martin Luther King,

Jr., and then Jesse Jackson. I think the accomplishment of these

individuals is an indication of his extraordinary capacities and

leadership and his support. Many of the black leaders have been

recognized as outstanding, but few have had proteges or lieutenants who have also achieved outstanding things similar to or even

in some instances even surpassing their leader, but Martin Luther

King, Jr., nurtured these kinds of individuals, and I think Jesse

Jackson's scale as a politician is a direct link to the Martin

Luther King era and his close association with him.

Blacks have not occupied high office, and I take that as a

clear and present example that racism still exists in the United

States. I do not link up with those who suggest that the issue

now in the United States is class and that is stratification and

that being a member of the underclass is the basis why there is

discrimination. No, I see discrimination continuing at all levels

in the United States. We have never had more than one person

who's been a member of the Supreme Court who was black. We have

never had but one senator in the United States who's been black.

We have never had a vice president or president who was black or

any other racial minority. We have never had a governor who's

been black, so I think that there is clear and present evidence

that discrimination on the basis of race and I would certainly say

on the basis of gender is still available and visited upon any who

permit themselves to be discriminated against.

One of the things, of course, I have minded over the years is

that people can discriminate against me, but I don't tolerate it.

People think that sometimes that is a silly statement, but I

don't, I just don't tolerate people who discriminate against me.

They can try and they can do it, and they will, but I never accept it, so I have given myself the role of trying to reform the whole

society, and of course that is a job that is too big for any one

individual to take on. But that's what we were taught at

Morehouse, and that's why Martin Luther King, Jr., did a long

range toward reform in this society, and I think others who

believe as he believed who are continuing that process, that

certainly is my goals, and anytime I experience injustice, I

accept it as my responsibility to put it down to overcome it. I

ran into it as a member of the Episcopal church. I later joined

the Episcopal church in the United States. As you recall, my

boyhood church was Christian Methodist Episcopal Church, but the

Episcopal Church which is a branch of the Anglican communion is

the church I finally joined after I finished my graduate work.

One reason I joined is because the church in Syracuse University

had a very fine choir, and I wanted to do something different from

reading, and I joined that choir. Incidentally, the person who

became my wife sang in that choir, so that was a wonderful

experience joining the Episcopal Church, but as I became a member

of the Episcopal church and participated in it, I finally was

elected to vice president of the house of deputies at the general

convention, and I was twice elected vice president and may have

been elected president of the general convention of the house of

deputies. The decision-making apparatus of the Episcopal Church

is divided between a house of deputies consisting of clergy and

lay people and the house of bishops. Those two bodies have to

concur for any proposal to become church law, and as one can see I

was a high official in the Episcopal Church. At that time there

were three million members, which was a significant body to

preside over, but the Episcopal Church found itself caught up in

the tentacles of sexism. It would not permit women to be priests,

and at one time women could not even be delegates to its general

convention. I thought that was unjust, and when the women decided

to overthrow that ruling that they couldn't be priests by seizing

the priesthood in effect, and that is what they did in 1974.

Eleven women found three bishops who were willing to ordain them.

In Philadelphia at the Church of the Advocate which was deep into the black community, eleven women, all white incidentally, I

thought that was significant that they had found a black church in

which to be ordained, they were ordained to the priesthood. I was

an officer of the Episcopal Church at that time, but I opposed the

whole hierarchy and I preached the sermon at the ordination of the

first women priests of the Episcopal Church in the United States.

Of course I resigned in protest and never was elected president,

but I think I was carrying out the message that I had been taught

during the days of my youth and my undergraduate education that is

never to accept injustice. High office and prestige is no basis

for knuckling under to injustice, and that's been a tenet of my

life over the years. So wherever I find injustice, I am sorry, I

have to oppose it. That's why I say I never accepted discrimination. One may discriminate against me simply because I have no

power to overcome it, but if I see any opportunity to resist it, I

will.

I have been asked by Mayor Raymond Flynn to be a consultant

to the City of Boston to help it develop a new student assignment

plan, and the invitation came in 1988 to see if we could put

together a plan that might be ready to fly in the fall of 1989.

There is an interesting background to this invitation. Mayor

Flynn came over to the Harvard Graduate School of Education to

obtain a degree in education several years ago. He has always

been interested in education, and he wants to be recognized as the

education mayor of Boston. He was from South Boston at that time,

and in the early days of school desegregation back in 1974, '75,

'76 he was opposed to integration in the schools. He was not as

vitriolic about his opposition to it as some politicians were at

that time. Nevertheless he opposed it, but when he came to

Harvard to matriculate for a graduate degree he was assigned to me

to be his advisor. I was on the faculty at that time. It was an

interesting relationship, and I would say we both out of that

became friends. Several years after receiving his degree he asked

me, because I had served as a consultant in several communities

throughout the United States putting together school desegregation plans, to see if we couldn't do something for Boston, and we

tried. We have put together a plan for Boston that is receiving a

wide amount of support, although there are some people who are

still opposing it, and this time the opposition is coming out of

the black community, whereas in 1975, '76 the opposition came from

the white community, so it indicates that none is immune to

protesting major social change. Nevertheless, we put together a

plan, one of my graduate students and I, his name is Michael

Alves. The plan is called controlled choice, which divides a city

like Boston into about three relatively large districts that

encompass about fifteen to twenty thousand students each and makes

available maybe twenty schools or so from which families may

choose, and the fact that they can choose a school means that the

parents are running a referendum on the quality of schools because

those schools that they don't choose are schools that are known to

be in need of fixing. They are not attractive, and so our plan

then provides choice.

But you can choose a school only if you are within the racial

ratio that is required for the school, and the racial ratio

required for each school is the same as the racial proportions of

school-going children within each zone, so there is general

proportional access to all of the schools. You can choose a

school, and the schools that are least chosen are the schools that

are least attractive, and in this way the community knows where to

put its money to enhance education. You put your money in those

schools that are least chosen. So we have a plan that does three

things simultaneously. It encourages choice, it promotes and

guarantees desegregation, and it enhances education, and the

beauty of controlled choice is that it accomplishes all of these

goals simultaneously. There have been people who have tried to do

the same thing in the past, but they tried to do it singly or

serially. They tried to do it with magnet schools only, which

would enhance learning environments, but these never could

accommodate more than one-fourth to one-third of the students in

the city. They tried to do it with voucher systems which may permit students to go to suburban communities and other communities, but it left bereft urban systems of education, and they

tried to do it with freedom of choice, and freedom of choice is

never desegregated schools. We have taken those three methods and

have accomplished them simultaneously, and this is where we think

the controlled choice plan is going to have some benefit in

Boston. It is receiving the kind of resistance that most major

change receives in Boston, which is a very political system and

very political city, but I predict that we will see some version

of it come into being in the fall of 1989, and Boston which has

the reputation of being one of the most violent schools when the

court first ordered desegregation in 1975 is probably going to

achieve the reputation of being one of the most desegregated big

cities as we move into the 1990's.

I have been retained as a planner in San Jose, in Milwaukee,

Dallas, Houston and in Boston and in St. Lucie, Florida, and

seldom have I come into contact with another planner who is black,

and I think this has been one of the problems with school desegregation in the United States from the 1970's on. Blacks and

hispanics usually have been members of the plaintiff class that

have alleged discrimination, and their allegations oftentimes have

been sustained by the court. So they win the court case to

achieve desegregation, but then the local school system is

obligated to plan for their redress, and the local school system

usually retains only white planners to plan a program of desegregation, which means that the planners usually come forth with

the techniques that are least offensive to whites instead of

techniques that redress the grievances of blacks or hispanics, who

are the plaintiff class. I have always retained in my planning

group blacks and whites, and I have urged other planners to do so

because I think that self-interest is one of the basic motives for

social action, and you ought to have a diversified group so that

the self-interest of the range of people in society can be taken

into consideration in the planning. Most people have tried to

approach planning as an intellectual activity, as a logical activity. It is that, but more it is a situation that is planning

that fulfills the interests of all of the constituent groups in a

community, and some representation of those constituent groups

ought to be on the planning team. I have found that planning

teams that are diversified racially have a better possibility of

fashioning a plan that will do the things that controlled choice

will do, that is guarantee desegregation, provide choice, and

enhance education all at the same time.

Judge W. Arthur Garrity, of course, is one of the judges in

the United States District Court in Boston. There were numerous

proposals for dealing with the alleged segregation and the actual

segregation which the court found to exist. Because there were so

many proposals, the court asked a panel of masters, masters in the

legal sense of finders of fact, to evaluate the alternative

proposals for remedying the segregation, and if the panel of

masters did not find any plan worthy, then they could submit a

plan of its own. In submitting a plan of its own the judge asked

the panel of masters to take the best features of the many

different proposals that had been filed with the court. I served

with Edward McCormack, Jacob Spiegel, and Frances Koppel as one of

the four on the panel of masters, and we worked with a panel of

two court-appointed experts, Robert Denton and Marvin Scott, and

together we fashioned the plan that the court ordered back in

1975. Having served in several communities as an expert witness,

I consulted to the court or to the defendants, or to the plaintiffs, and having studied school desegregation on a comparative

way in about fourteen different communities, I was pleased to have

the opportunity to return to the Boston scene more than a decade

after I had first helped fashion a remedial plan to see if we

couldn't fix it right this time. I think on the basis of a decade

of insight, information, and knowledge we probably are going to be

able to help Boston become, as I said earlier, one of the most

desegregated cities in this nation that also has an enhanced

educational system.

Judge Jacob Spiegel was a retired justice of the state

supreme court. Frances Koppel was a former commissioner of

education for the United States and also a former dean of the

Harvard University Graduate School of Education. Edward McCormack

was former attorney general for the state of Massachusetts. I at

that time, of course, was a professor in the graduate school of

education at Harvard.

Busing is a phony issue because in the urban community we use

transportation to go to all kinds of activities. Most of us use

transportation to go to and from our jobs. Most of us use transportation to go to and from shopping centers. Most of us use

transportation to go to and from religious institutions. So

transportation is an endemic part of the life of urban communities, and to fixate on the use of transportation that goes to and

from school is the basis for accepting or resisting desegregation

is silly. Actually, there is no evidence that indicates that the

location of a school nearby or far away has anything to do with

the quality of education that's offered in that school. So what

we have done in Boston realizing that transportation is really a

smokescreen and not the real issue in any urban environment, we

have devised a plan where neighborhoods are no longer assigned to

specific schools. What we say our plan does is break the hostage

relationship between real estate interests and educational

interests. Now that the whole zone can choose all of the schools

within a zone, schools know the professionals in schools are

obligated to make themselves attractive, which they did not have

to do in the past when the students from a certain neighborhood

were assigned to a certain school. That's why we said busing is a

phony issue. Transportation has never been the major issue in the

urban scene with reference to participation in any institutional

system including the schools.

The black members said that they voted against the plan but

not for the same reasons. They have not all revealed the reasons

that they voted against the plan. Incidentally, there are four black members on the School Committee of thirteen in Boston. Some

said they voted against it because they wanted to see funds for

enhancing education made available up front. Our plan recognizes

that politically no mayor can give the School Committee a blank

check for funds to enhance the schools, so our plan places

pressure upon the funding sources in the city to make funds

available for those schools that are doing least well. We have

used the model of the National Basketball Association. The teams

that do least well are those that have the first opportunity to

obtain the new talent that is coming on the market from graduating

from college basketball teams, and the same is true in our plan.

The schools that seem to be chosen less frequently are those that

are candidates for funds for enhancing themselves. So we had

devised a plan where the funds being made available comes after

the referendum, after the choice cycle. Many of the black members

felt that the funds ought to be up front. We don't object to

funds up front, but one of the reasons why we did not include them

in our plan is because, if funds were made available without

having the choice cycle, it is one way of identifying schools that

ought to receive those funds, then they probably would be

appropriated the way they have been in the past. Those schools

that got extraordinary resources tend to be those schools that had

principals who had pull, parents who had clout, and we felt that

we ought to be able to overcome that kind of idiosyncratic way of

allocating funds, and we ought to have a public documented way of

allocating funds to the schools that need it the most. So that

was one reason why the black members opposed. I think another

reason is they have been against discrimination over the years as

many blacks have been, and while their interest in this instance

was to lobby the mayor and city officials for more funds, they had

not developed tools for doing this, and therefore fell back upon

the old tools that they had had, and those were the tools of

resisting discrimination. So I think that that was another reason

why the black members opposed. They simply were using the tools

of discrimination, the allegations of discrimination, as the basis

for resisting the plan unless they could get funds appropriated up front.

Text mounted 9th October 2013; image mounted 12 October 2013 -- rcwh.

Segregated Dallas childhood

Segregated Dallas childhood