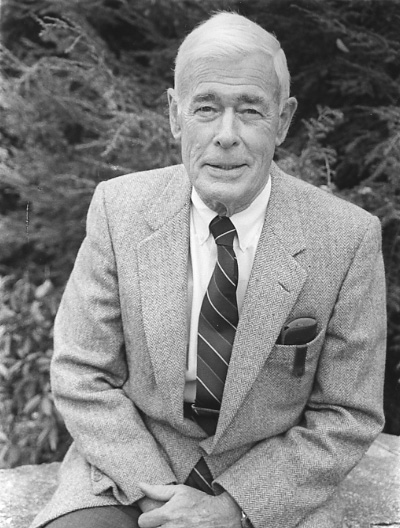

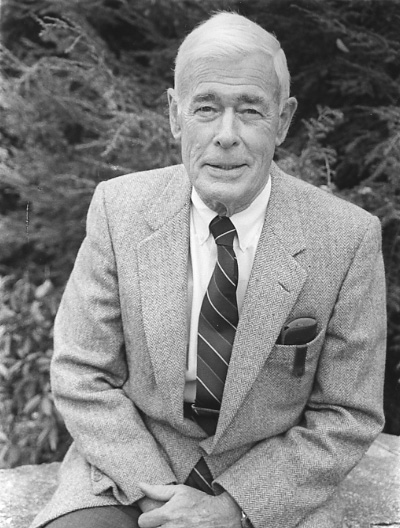

Sinclair Weeks, Jr.

196 Elm Street

Age 73

Interviewed November 7, 1996

Concord Oral History Program

Renee Garrelick, Interviewer.

I understand the Concord Library has a growing collection of president’s papers and the Eisenhower papers are now being drawn together by the library at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, which is named after President Eisenhower’s brother. These papers are in the process of being assembled and I thought it would be interesting for the Concord Library to have the volumes. I believe there are 13 or so to date, this being the fall of 1996, with more to come, and I’m told by the people in Baltimore that they hope to have the project finished by the turn of the century. I’ve looked at them myself and they are very interesting and primarily for the scholar.

I understand the Concord Library has a growing collection of president’s papers and the Eisenhower papers are now being drawn together by the library at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, which is named after President Eisenhower’s brother. These papers are in the process of being assembled and I thought it would be interesting for the Concord Library to have the volumes. I believe there are 13 or so to date, this being the fall of 1996, with more to come, and I’m told by the people in Baltimore that they hope to have the project finished by the turn of the century. I’ve looked at them myself and they are very interesting and primarily for the scholar.

My father, Sinclair Weeks, was a member of President Eisenhower’s cabinet as Secretary of Commerce and was instrumental in implementing the Federal highway system. For all of us old enough to have driven across the country before the war, we know what an expedition it was. I think the President realized through his war experiences in Europe and his observation and knowledge of the German Autobahn system that a country’s economic and in that case military progress had a lot to do with its efficient means of transportation. When he came back and was subsequently elected President, this was a project which he thought was very important to develop in this country, and of course, time has proven the wisdom of that decision.

President Eisenhower was so impressed with my father’s work that when he wrote the book, Mandate for Change, he included this statement, “This great highway system will stand in part as a monument to the man in my cabinet who headed the department responsible for it, and who himself spent long hours mapping out the program and battling it through the Congress, namely Secretary of Commerce Sinclair Weeks.” While this was something my father was concerned with and spent a lot of time doing, there were a number of other projects in those days of the ‘50s including the opening of the St. Lawrence seaway, developments in air transportation, a lot of the trade negotiations with countries in Europe and Asia, the improvement in the weather system and so forth. That, of course, is another story.

My father was also a United States Senator during the time of Roosevelt’s administration during World War II. Henry Cabot Lodge, then a Senator from Massachusetts, resigned to go into the service and Leverett Saltonstall, at that time the Governor, appointed Mr. Weeks to fill out the term. I believe there were two or three years left of that Lodge term, after which when the next seat came open, Saltonstall himself ran and was elected.

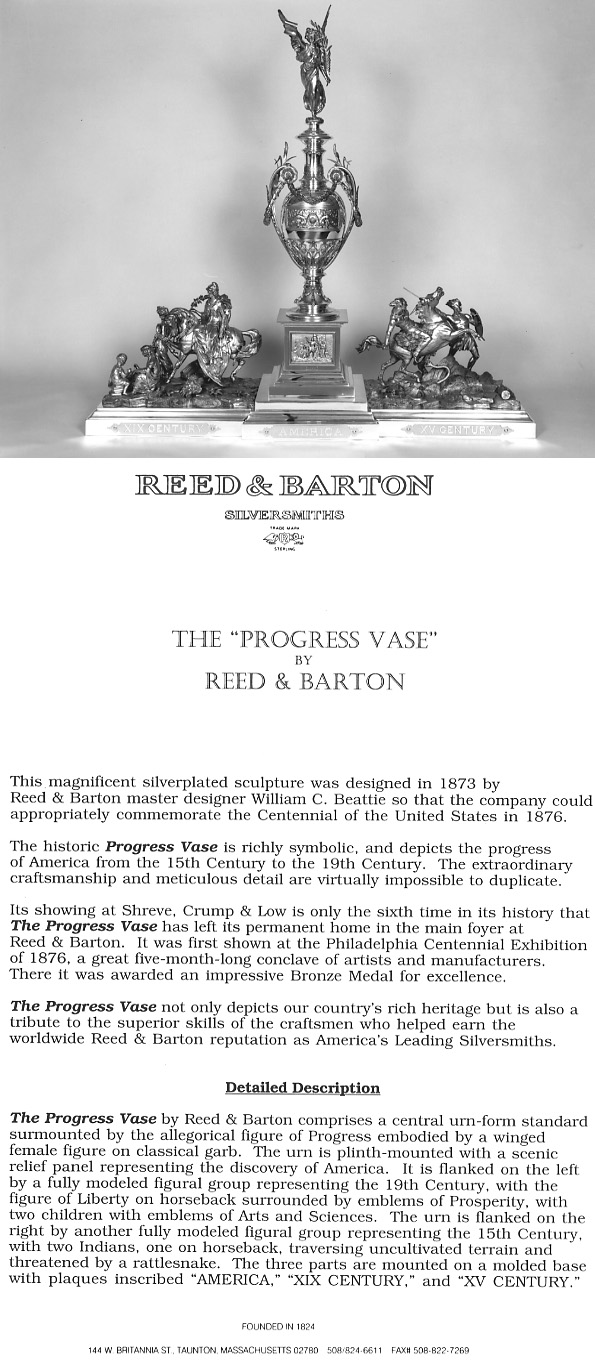

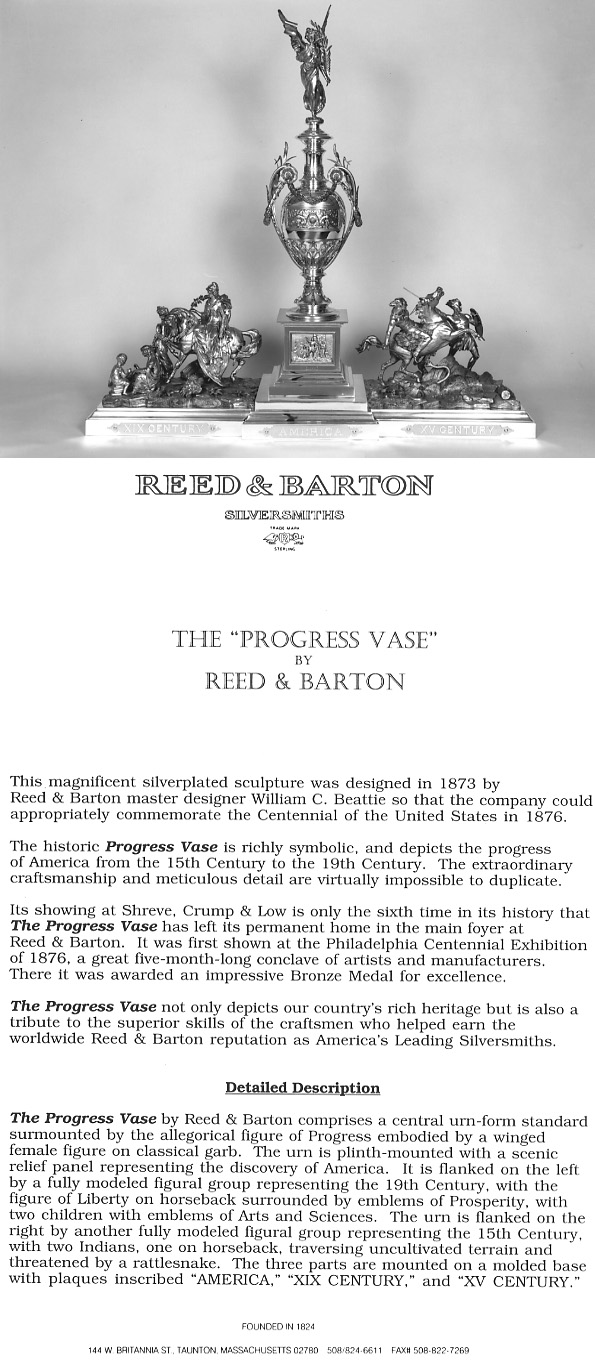

This is a story that I heard of after the war because my father was not inclined to blow his own horn. During the wars the country had, over the years since Theodore Roosevelt’s day, been building the “great white fleet” in the early part of the century and improving America’s Navy. We and certain other companies in our industry were busy building dining services for the battleships in particular, and later, when the carriers were developed, for them as well. During World War II Reed & Barton received a rather substantial order from the Navy Department for silverware to be used on a number of the ships, and it seemed to my father that spending money during a national emergency for silverware for the fleet was a terrible waste of money and entirely unnecessary. Through his Republican connections, he knew Colonel Frank Knox who was then the Secretary of the Navy and wrote him mentioning this and suggesting that there were more important things to spend the nation’s money on and it would be much appreciated if the order to his company were canceled, and it was! I think the Secretary was glad to know about it. My father was a life-long Republican, as was his father, and he believed the least government is the best government. It’s getting more and more difficult to follow this path.

Reed & Barton is a family business of which I was President/CEO and am currently Chairman of the Board. It began in 1824 in the city of Taunton in southeastern Massachusetts when two men, one who ran a jewelry store, decided they would independently reinvent the wheel, in this case determine how Britannia pewter was made. In those days even though we had defeated the British in two wars, they were still very jealous of their economic secrets and anxious to maintain as much of the American market as possible. These two men developed independently the formula for Britannia pewter and started making the metal in what was then known as the Taunton Britannia Manufacturing Company. Henry Reed was a native of that part of the state and was born in 1810, and incidentally went to work in 1828 at the age of 18 and worked until shortly before his death in 1901, which is a record of being on the job for 73 years ¾ something you don’t hear of much these days. Mr. Reed, my mother’s grandfather, was a spinner which is one of the trades in the silverware industry ¾ the spinning of metal over a chuck to create a shape in this case a holloware body. Holloware being everything made of metal in this industry except for knives, forks and spoons which are referred to as flatware. The company’s history, which is included in the book called The Whitesmiths of Taunton published in 1940 by the Harvard Business School, chronicles these development years when the company started making pewter, Britannia metal. In the 1840s when the process of electro-deposition or the plating of one metal on another was developed in Europe, Henry Reed brought over from England a plater and we starting plating silver. Later in the century at the time of the discovery of silver in the Comstock Lode in Nevada, silver became abundant and therefore less expensive and the company went into the manufacture of sterling ware. So we came into this century making pewter holloware, plated and sterling holloware and flatware, and then, in the 1950s following the cessation of the Second World War, the company got into the manufacture of stainless steel flatware However, resources for that product have largely moved to the Far East, as first the Japanese then the Koreans, and now to an increasing extent, the Chinese with their advantage of cheap labor and adequate tooling have largely taken over the American market.

If I remember my history, Paul Revere died in 1819, and of course, we were getting going shortly thereafter. The Bureau of Labor Statistics using statistics that were compiled in 1994 said there are in the United States 6,572,000 industrial establishments, of which 398,000 are manufacturing establishments. Of these 398,000 manufacturing establishments which employed over 18 million people, 5,248 employed over 500 people. To me the interesting thing was that 332,000 or 83% of these manufacturing firms employed less than 50 people. Most people associate the American economic scene with big business, but when you consider that 83% of the manufacturing firms in this country employ less then 50 people, you realize that this is a vast economic landscape, and most of the companies, of course, are privately owned. So the fact that Reed & Barton has always been privately owned is not unique at all.

My great-grandfather, Henry Reed, would be an example of the skilled craftsman at his workbench guiding production and very visible to his workers. He liked the factory and he liked the people with whom he worked. He was primarily a factory man all his life. He had, of course as the company grew, people who handled the marketing and finance. Of course, he kept an eye on the whole thing, but his main concern was the shop, and as a result the company acquired a reputation for good service and very good quality, which we still think is our hallmark and the most important asset we have.

My grandfather, William B.H. Dowse, was a lawyer and more the financier. Certainly he wasn’t a factory man such as his father-in-law. It’s interesting that over the history of the company, about 175 years, there have been only six presidents, which is unusual and two of them have been members from outside the family. We’ve tried over the years to put the best people in the jobs that they can fill well.

Considering the relationship of the company to the country, a subject that could start a long discussion, I think the best thing that can be said is that this medium-sized business has been very important to its community, and as long as I can remember, going back to the early days before I was connected with it, the company has always taken the lead in the various programs and fund drives in the community: the Chamber of Commerce, the United Way and so on. We feel that the business has a social responsibility which also is just good business to be an important and valuable citizen. I’m glad to say that Al Krebel, my successor, is carrying on in this same tradition.

At the turn of the century the jeweler was the predominant distributor of silverware ¾ flatware, holloware ¾ of Reed & Barton products. Up until the 1920s, the jeweler had such a stranglehold on the business that he could put his own mark on the product. For example, we have for many years made silverware for Shreve’s in Boston, and on old Shreve’s services, it is not marked Reed & Barton, it’s marked Shreve, Crump & Low. In the ‘20s, the companies in the industry broke this stranglehold through advertising and so forth and developed their own brand names. I know of only one situation now where the selling organization, the store or a group of stores, puts their own name on the product. We have spent a lot of money and so have our competitors to build our brand names, a development of great importance.

First it was jewelry stores, then it was department stores as well, then in the last 20 years, there have been more and more discount outlets. Within the last 15 years, because so many of the normal distributors, the jewelry stores and the department stores, require a high markup, many discounters have come in under this “tent” selling through catalogues directly as well as retail. Our biggest accounts today are not the department stores. The next stage of that development in marketing, of course, came with the development of the factory outlet. At this time the company has 11 stores under its own name all the way from Kittery in Maine to central California.

We have a number of different subsidiaries in the corporation: in our housewares division we sell a great deal of stainless steel through QVC; in our Eureka Manufacturing Company, traditionally a manufacturer of jewelry and silverware chests, within the last two or three years, has become a very large supplier of humidors. The cigar business is making a big comeback!

We have recently acquired a company that makes fine lead crystal, the Miller-Rogaska Company, an American marketing firm buying much of its product from Eastern Europe. This, in my tenure going back to the early ‘60s, is Reed & Barton’s fourth diversification effort to look for ways in which to broaden the base of business and to permit us to be less dependent on the silverware and the traditional products of the company.

In terms of volume, the great years for this industry were right after the Second World War, the ‘50s and ‘60s. If you measure volume as we do in terms of troy ounces of silver, the industry is shipping today about a third in ounces of what it shipped 30 or 40 years ago. Interestingly enough the price of silver has not gone up substantially. In fact, in 1979 before the run on silver orchestrated by the Hunt brothers in Texas, the price was $6.50 in January and that is higher than it is today. In sterling the rule of thumb was to measure the retail price of a spoon or fork as four times the price of the metal. If for example, silver was $5.00 an ounce and there was an ounce and a half of silver in a fork, a total of $7.50, the fork at retail would be sold, when there was price maintenance, at around $30. Going back to distribution, of course, these margins have been cut at every level including the manufacturer’s level and when you add to that problem the fact that we’re shipping fewer ounces, diversification becomes necessary.

When I came into this industry in 1961, after 14 years in another, there were nine independent companies in the silverware industry. Today there are three. The three today are Oneida, Lunt and Reed & Barton. Well known companies like International Silver, the Wallace Company, both in Connecticut, the Towle Company in Newburyport, MA, the Kirk Company and the Stieff Company in Baltimore, all of these have been absorbed into larger businesses. It’s Brown Foreman and the profits from Jack Daniels which have acquired many of our competitors.

Going back to the fact that the demand was great in the ‘50s and ‘60s, there was an enormous pent up demand after the war for silverware and flatware. There was a very high rate of family formation. People were getting married, building homes, furnishing their homes. There was still a lot of home entertaining, much more than there is today because in those days there weren’t so many working women. However to a large extent in the South today, women still take a great deal of pride in entertaining at home, in setting a nice table and so forth. This is changing and the results you can see in the volume of the industry.

Way back before Christ was born, every currency between the Nile and the Euphrates was based on silver. Then the knowledge of silver mining was taken by the Greeks, many of whom had settled in Asia Minor, to Greece and the great mines at Laurium financed the Athenian wars against the Persians. After Greece fell under the control of the Romans, the latter took the knowledge of silver mining to Spain, by then a part of the Roman Empire. The Spaniards mined rich and extensive mines and began a commerce with India through the Red Sea in exchange for the silks, satins and jewels of that subcontinent. It’s curious that the largest source of silver above ground today is still around the ankles, wrists and necks of the women of India. When the new world opened up, the Spaniards took the knowledge of silver mining to Central America, and the next important development in silver mining were the mines in Mexico, in Peru and so on. Then the next development came in our own country with the well known and large strike at Nevada in the Comstock Lode, which, as I said earlier, had a lot to do with getting this company and our competitors in to the sterling business. Today the four major producers of silver in order of importance are Mexico, Canada, then United States and Peru exchanging third and fourth position. We’re still a major producer but not the largest.

Fine quality flatware still requires handwork ¾ the insides of the tines, the grading of the blank so that it is not of a standard thickness, the polishing of the edges, the depth of the slots of a fork, the evenness of the points at the end of a fork ¾ these are all things that we associate with quality. If you look carefully at a cheap piece of stainless steel, for example from South Korea or China, you’ll see the difference between something that is well made and something that is not.

Chasing is one of the old skills which you still see on fine holloware. This is the process of cutting or hitting with small tools a design in the metal either on a flat surface or a curved surface and is sometimes done to accentuate the process of repousée; raising the metal by the use of stakes from the inside so that if you look at a piece, for example a body of a teapot, it wouldn’t all be design, it would have parts of metal that have been raised to accentuate and add beauty. We have fewer of these craftsmen. There were some good shops in England but there’s no firm left in the world that makes the fine holloware still made at Reed & Barton. Before I retired in 1988 I went to the Guild Hall in London and had dinner with the man in charge of the silver collection. There was an exhibit in the mid ‘80s of the work of Paul DeLamerie, one of the great and perhaps the greatest of the silversmiths. One of the pieces sent to this country to make its appearance in a traveling exhibit came back to England, the director told me, in pretty bad shape. They looked and looked and found only one man left in England in his 80’s who could repair it. It’s now down in the vaults. Much of the silverware from the Queen Anne period (early 18th century) was made by a number of Huguenot silversmiths who fled to England and DeLamerie was the best known. A number of them came to this country, one of whom was a man named Adolphus Rivoire who changed his name to Revere and became father to the famous silversmith and “equestrian” Paul Revere.

Reed & Barton made the Olympic medals for the games held in the summer of 1996. That was an interesting exercise and we were very proud to receive that contract. It worked out very well. We made something over 1800 of these medals, the gold, silver and bronze. Incidentally, the gold medal is not a solid gold metal. It’s really made of two metals, two gold layers over an interior of silver. There is something like $67.00 worth of gold in each gold Olympic medal, but if the winners who took them home should cut into them to see if they are all gold, they are going to be disappointed.

Of the three independent companies left in the country, Oneida is by far the largest, but the Oneida people have never been important in terms of sterling ware. They are primarily known as the major producer in this country of stainless steel. Of the other two, Reed & Barton is somewhat larger than Lunt.

I was president from 1972 to 1988, and we were very concerned in the late ‘70s with the rise in problems that had to do with ecology. In 1978 we sold some bonds, the revenue from which committed us to do a major effort in handling waste water and solid waste treatment. I’m glad to say we did it “early.” Eventually everybody had to do it (and it was right that everybody had to do it). The longer you put it off, the more expensive it is. In 1979 on the second of our acquisition programs, we acquired Kurt Gutmann Jewelry which was located in New York. About that same time the famous Hunt brothers in Dallas attempted to drive up the price of silver and for a while they were quite successful. The silver as I remember in January 1979 started out around $6.50 a troy ounce and by the end of January of the following year, it was around $48.00 an ounce. Six weeks later it crashed and went down to around $10.50. In those days we used to carry about 2 million ounces of silver, and so on one day our silver inventory alone was worth $100 million and six weeks later it was worth $21 million. Running a business under these conditions can be exciting, I can assure you. As I said earlier, the price of silver hasn’t changed a great deal since that time.

In 1980 looking for another source of medium-price plated holloware, we acquired The Sheffield Silver Company of New York which was eventually consolidated into Reed & Barton factories in Taunton, but we kept the name and still use it. In 1981 we decided to try out the collectors business á la Franklin Mint. We started up a company called the New England Collectors Society which operated very successfully for a number of years. It is no longer in business. That industry is not as dynamic as it was.

I think the early part of the ‘80s was one of the most interesting periods because we went through numerous changes in distribution. There was a lot of deep discounting litigation. At one point we sued five of our competitors to prevent them from authorizing, directing or suggesting or otherwise naming any of the retailers to advertise their products at discounts from suggested lists unless a substantial part of the merchandise had previously been sold at those suggested prices. This caused a great deal of trouble. In the long view of things, it was just a temporary holdup because there has been a lot of discounting and it became quite serious in that period in the early ‘80s.

There are laws in this country which prevent you from price maintenance down the retail chain. We sell our products to everybody in the same quantities at the same price, but it’s tricky. It’s a tough world out there. Discounting still goes on in the industry. Peoples’ habits have changed. How many catalogues come into all our homes especially during the holidays? People don’t do as much shopping. If they’re familiar with the kind of quality that you get from a catalogue, why not order from the catalogue? We don’t do our own catalogue business, but our products are in catalogues of our customers.

We deal with major department stores like Bloomingdale’s, Neiman Marcus, Marshall Field, etc. Neiman Marcus is still a very good one and “Field” still has its reputation, but the department store industry isn’t what it used to be in this particular business. Discounters have grown very large and it’s going to be interesting to see what happens next. I imagine that there will be more and more specialty stores particularly where there are population densities which can support them and where their advertising can be important. Everybody at the retail end is looking for products that nobody else has. Reed & Barton’s current distribution, outside of our own stores, is primarily through discount stores, what’s left of good jewelry stores (you can count them in this country on the fingers of one or two hands), and in department stores.

In 1982 we acquired the Scientific Silver Service Company and out of that grew our housewares division, which, of course, presents a lot of issues. If a company known for quality products is going to sell housewares merchandise into different departments in the stores, how will it affect the reputation of a quality brand name? At what point do you denigrate your name? This is an important consideration, and you never know when you might be stepping over the line. We do a big housewares business, and I think that generally people who buy our stainless steel (for example in the housewares department) realize that it isn’t comparable to fine plate or sterling, but it is the best steel. It’s a good value in it’s niche, so to speak. Beyond that the last endeavor that we were in until this recent acquisition was the establishment of a joint-venture company with Cartier, the French jewelers, which proved to be unsuccessful. It was something we went into with our eyes open and with the encouragement of our Board in an attempt to make a really very, very expensive fine line of china, sterling flatware and crystal. I was just in Cartier’s the other day and noticed that some of those china patterns that we developed for them are still being sold and are very popular.

Reed & Barton will be 175 years old in 1999, and we look forward to an interesting and successful future.

Text mounted 2 Feb. 2008; revised and images mounted 15 June 2013 -- rcwh.

I understand the Concord Library has a growing collection of president’s papers and the Eisenhower papers are now being drawn together by the library at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, which is named after President Eisenhower’s brother. These papers are in the process of being assembled and I thought it would be interesting for the Concord Library to have the volumes. I believe there are 13 or so to date, this being the fall of 1996, with more to come, and I’m told by the people in Baltimore that they hope to have the project finished by the turn of the century. I’ve looked at them myself and they are very interesting and primarily for the scholar.

I understand the Concord Library has a growing collection of president’s papers and the Eisenhower papers are now being drawn together by the library at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, which is named after President Eisenhower’s brother. These papers are in the process of being assembled and I thought it would be interesting for the Concord Library to have the volumes. I believe there are 13 or so to date, this being the fall of 1996, with more to come, and I’m told by the people in Baltimore that they hope to have the project finished by the turn of the century. I’ve looked at them myself and they are very interesting and primarily for the scholar.