AN ONLINE EXHIBITION OF WALDEN POND IMAGES

Offered by the Concord Free Public Library in Celebration of the 150th Anniversary

of the Publication of Henry David Thoreau's Walden in 1854

Introductory Essay by W. Barksdale Maynard

Essay copyright 2004 by W. Barksdale Maynard

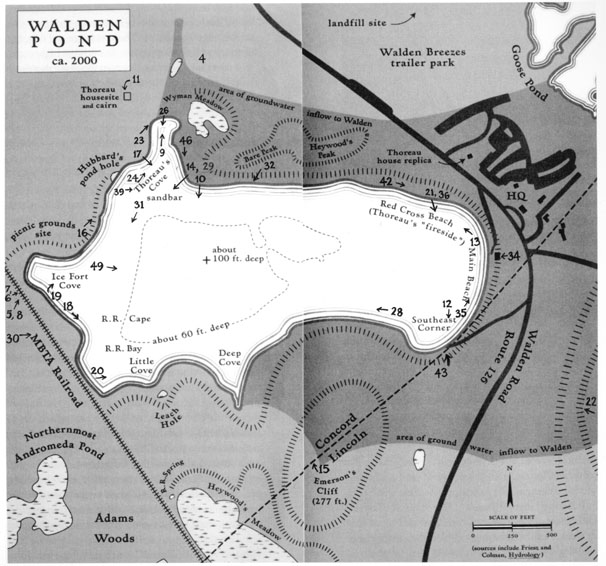

For a locator map linking numbered images referred to in essay to display images, click here.

Image numbers in essay are also linked to display images.

"There is enough that is singular about this pond, to warrant a stranger in going a little distance to view it," a newspaper reported in 1821—one of the first published references to Walden, a place Henry David Thoreau would later make world-famous. The 62-acre pond lies just fifteen miles west of Boston, but it remains surprisingly wild-looking today, as it is surrounded by protected woodland (38). Concord Center is a half-hour’s walk to the north, and in my new book, Walden Pond: A History, I have tried to emphasize the intimate historical connections between town, woods, and pond. Inspired in part by the teachings of his friend and fellow Concordian Ralph Waldo Emerson, Thoreau lived at Walden for two years, two months, and two days (1845-1847), seeking a philosophical retreat from society and taking time to write, away from the bustle of his parents’ boardinghouse in the village. Concord Free Public Library has a remarkable array of documents and images that illustrates the history of the pond, both before and after Thoreau’s time there. The 150th anniversary of his classic book, Walden, is the perfect opportunity to explore these treasures.

"There is enough that is singular about this pond, to warrant a stranger in going a little distance to view it," a newspaper reported in 1821—one of the first published references to Walden, a place Henry David Thoreau would later make world-famous. The 62-acre pond lies just fifteen miles west of Boston, but it remains surprisingly wild-looking today, as it is surrounded by protected woodland (38). Concord Center is a half-hour’s walk to the north, and in my new book, Walden Pond: A History, I have tried to emphasize the intimate historical connections between town, woods, and pond. Inspired in part by the teachings of his friend and fellow Concordian Ralph Waldo Emerson, Thoreau lived at Walden for two years, two months, and two days (1845-1847), seeking a philosophical retreat from society and taking time to write, away from the bustle of his parents’ boardinghouse in the village. Concord Free Public Library has a remarkable array of documents and images that illustrates the history of the pond, both before and after Thoreau’s time there. The 150th anniversary of his classic book, Walden, is the perfect opportunity to explore these treasures.

When Thoreau lived beside Walden, its shores were partly wooded, partly cleared (2). The environs—"Walden Woods"— were virtually uninhabited, but divided into woodlots, including one of Emerson’s on which Thoreau "squatted" (4). Thoreau worked as a surveyor, and his hand-drawn maps of this and other lots are today housed at Concord Free Public Library, which has recently made them all available on the Internet, an extraordinary resource (click here). Emerson also owned a high rocky hill to the south of Walden, from which he enjoyed a sweeping view of pond and woods, with Concord in the distance (15). Cutting of timber had greatly accelerated with the coming of the Fitchburg Railroad along the western shore in 1844, to Thoreau’s grief (30). He mentions the railroad often in Walden, as he heard and saw it clearly from his Cove (31) and housesite.

Thoreau chopped holes in Walden ice in March 1846, dropping a line to take a survey of the pond’s depth. He also drew its outline accurately for the first time (1), creating a map he later published in Walden (3). He commented frequently on the pond’s uniqueness—very deep, surrounded by steep-sided sandy hills (32), with no visible inlet or outlet, but many placid coves (20). "Thoreau’s Cove," exceptionally scenic, was central to his Walden sojourn, as he sited his house beside it, and every morning in summer he bathed there (9). Walden’s height constantly fluctuates, from very low when Thoreau first visited it in the early 1820s, to very high (12, 21). Only once in several decades does the elusive sandbar appear at the mouth of Thoreau’s Cove (29, 46). Walden in Thoreau’s day had only a faint "Indian Path" around it, and most walkers used the stony shoreline instead, so long as the water was low (22, 28). Well into the twentieth century the hillsides remained virtually trackless (16), although in places erosion began early (23).

Not long after Thoreau’s death in 1862, the western shore of Walden was radically transformed by construction of a picnic grounds (5), complete with swings and a boathouse (6). Additions were made over time (7) to accommodate big summertime crowds who took the Fitchburg Railroad out from Boston, and a footbridge led across the tracks to camping areas and a bicycle track (8). Thoreau’s fame was beginning to grow nationwide, and many pilgrims came to see his Walden housesite were outraged by the commercialism. Eventually the amusement facilities were damaged by fire and abandoned (18, 19). In 1872, Unitarian picnickers followed a suggestion of Amos Bronson Alcott’s and established a cairn as a memorial at Thoreau’s housesite, to which both picnickers and more serious admirers would add stones (11).

Throughout these years, the Emerson, Forbes, Hoar, and Heywood families protected most of the Walden shoreline from development, and gradually the forests grew up again (25), though they were still subject to cutting in places as late as World War One (26). Frequent fires caused by locomotive sparks had caused much devastation in Walden Woods, which looked increasingly threadbare. In 1922, the families gave their land to the state of Massachusetts as Walden Pond State Reservation, to be administered by Middlesex County (33). According to the deed of gift, "bathing" was specifically allowed, and thanks to the automobile, there were more bathers every year on the formerly quiet east end, where farm boys had long come to swim (13, 21). The changes were swift and dramatic, as recorded by a disapproving Herbert Gleason, pioneering photographer of Thoreau Country, whose invaluable glass-plate and film negatives are preserved at Concord Free Public Library (34, 35). By 1933 the county had installed permanent bathing facilities at Walden (36, 49).

Crowds grew much larger once the Concord Bypass (Route 2) cut through Walden Woods like a knife in the mid-1930s, allowing fast motor access from Boston and its suburbs. The new highway irreparably damaged the Walden vicinity (37). After World War Two, 35,000 swimmers came on hot summer weekends, and the sandy hillsides around the pond grew shockingly eroded (39, 44). The county commissioners in charge of the pond were blamed for neglecting the erosion problem even as they undertook a radical 1957 campaign of beach enlargement and road construction at the northeast corner, Thoreau’s beloved "Fireside" where he warmed himself in autumn (42, 43). The Thoreau Society sued the county to stop the "desecration," and the Massachusetts Supreme Court ruled that the damage must be reversed and that the commissioners should "aid the Commonwealth in preserving the Walden of Emerson and Thoreau." Some cribwork was installed to curtail erosion (45), but only in the 1990s was complete bank restoration belatedly carried out.

Boston’s urban sprawl reached Concord by the 1970s, when developments were first proposed for the top of Brister’s Hill along Route 2. In 1988 a grassroots organization, Thoreau Country Conservation Alliance, mobilized against an office park planned for Brister’s Hill and condominiums on nearby Bear Garden Hill. TCCA for the first time drew public attention to the historic and ecologically fragile region long called Walden Woods (50). Their courageous but struggling campaign was taken up by The Walden Woods Project, founded by rock musician Don Henley, which proved adept at fundraising, resulting in the rescue of critical parcels of land worth millions of dollars. Thanks in part to these conservation efforts, Walden Pond today retains much of its scenic beauty as captured a century ago by photographer Gleason (14), but visitation to Walden Pond State Reservation remains extremely heavy (700,000 per year), and many worry about the pond’s long-term future. An incredible one hundred million people may come to Walden this century for swimming, jogging, fishing, and to see Thoreau’s housesite—perhaps more pressure than the little place can bear. The reporter of 1821 who thought Walden sufficiently "singular . . . to warrant a stranger in going a little distance to view it" little imagined our crowded modern world and the conflicting interests that would vie for control of America’s most famous pond.

W. Barksdale Maynard teaches architectural history at Johns Hopkins University and the University of Delaware and is the author of three books, Architecture in the United States, 1800-1850 (Yale University Press, 2002); Walden Pond: A History (Oxford, 2004); and Buildings of Delaware for the Buildings of the United States series (forthcoming from Oxford).

|

Image numbers on map are hotspots to the corresponding numbered image in the display. Click on number to view image. This map is an edited version of that appearing in W. Barksdale Maynard's Walden Pond: A History. It appears here by Mr. Maynard's permission. |