Concord Physicians

Concord Journal, September 3, 1953

The list of Concord physicians is not over long for a town of Concord’s age. During the early days there were probably enough to give everyone a choice of doctors, and if 50 families did not support two doctors, their practice could extend throughout the county. On horseback or later in their chaise (pronounced shay) they travelled miles in the course of their duties. They never refuse to go to see a patient unless their knowledge of the nature of the illness, or of their own inadequacy, made it hopeless and then they often went in spite of everything. This meant the maintenance of the stable, for a horse would tire out before the doctor did, and the apprentice to the doctor, learning the profession at the age of twelve or thirteen, would of course double as a stable boy. Outstanding as citizens as well as doctors, their prestige made them invaluable in town affairs.

The first name in our records is that of Dr. Philip Read who lived on the Bay Road (Lexington Road) near the Cambridge boundary (in Lincoln where Swanson’s Pontiac Garage is.) He married a daughter of Richard Rice, a first settler, and was probably the only person in town with an education as good as the minister’s. He was brought into court in 1670 for criticizing Rev. Edward Bulkeley, son and successor to the Rev. Peter Bulkeley. Read said that he could preach as well as Mr. Bulkeley, “who was called by none but a company of blockheads who followed plow-tail and was not worthy to carry Mr. Estabrook’s books after him. (Rev. Mr. Estabrook was the young associate minister)”.

Then he was tried because he said that he thought the illness of one of his woman patients was caused by standing too long during prayers in church. He asked to be represented by counsel; this was denied, and he was fined 20 pounds. He moved away.

The next doctor, Jonathan Prescott, was also a blacksmith. Moving in from Lancaster at the time of King Philip’s War, he soon acquired property with three successive wives. The Block House on the Savings Bank site was his home. His son, Major Jonathan Prescott, “an accompanied physician, but excelling in surgery,” as his gravestone says, died in 1729. He probably lived in a house on Lexington Road which his wife, Rebecca, inherited from her father, the lawyer Peter Bulkeley Esq., son of Edward Bulkeley. As may be seen from his title, he combined military service with his profession, which gave him opportunities to practice amputations, then the accepted remedy for gunshot wounds.

James Minot, who came to Concord in 1680 and died in 1735, lived in a house which is part of the Colonial Inn and preached as well as practiced. His grandson, Timothy Minot, graduated from Harvard after preparing for college with his father, Timothy, Sr., who was the town schoolmaster. He lived in the old Rev. Peter Bulkeley’s house, which, after Minot’s death, was bought by the county and later remodeled as the Middlesex hotel. It was burned in 1844.

Dr. Simon Davis, son of Lt. Simon Davis, lived near Barrett’s mill and practiced principally as a surgeon. His son, Dr. John, succeeded him and lived until 1762.

Meanwhile on Nashawtuc hill, Dr. Joseph Lee (from Salem) had settled and combined medicine with farming. His son, Dr. Joseph (1716-1797), practiced during the first part of his life, but his Tory unpopularity and his participation in Church politics made him turn away from medicine.

Two of Dr. Jonathan Prescott, Jr.’s sons carried on the family tradition after graduating from Harvard. Dr. John Prescott lived on Sandy Pond Road (then called the road to Flint’s farm) in what is now George Root’s house. Born in 1707, he graduated from Harvard in 1727.

He was interested in the expedition to Cuba for which he enlisted 100 men in the neighborhood, very few of whom returned. After his own return in 1743, when he must have been an expert in tropical diseases, he was called to London, where he contracted small pox and died in the same year. The British government paid a pension to his widow until long after the Revolutionary war. Dr. Abel Prescott, his brother, lived in what is now the rear of Dr. Fallon’s house on Lexington Road next to the Orchard House. He lived until 1805 and “enjoyed a most extensive professional patronage. His practice extended through the county.”

A new era not only in Concord but throughout the country began with Dr. John Cuming. The son of Robert Cuming who had come from Scotland during the rebellion of 1715, and moved from Boston to Concord, where he ran the big farm on what is now the Hawthorne Lane-Turnpike corner. His son John inherited a large part of his father’s estate.

He had a good academic education and a regular course of medical studies, probably (as was the custom in those days) as assistant to a practicing physician. Harvard gave him honorary MA in 1749. From 1745 until 1763, he was in the French and Indian War, was wounded by a ball that lodged in his hip, where it remained until his death. He was captured by the Indians and carried to Canada, from which he was exchanged. He visited England where he studied medical education and, after a long practice in Concord and the County (his home was the house at the Reformatory circle), he provided a large bequest to Harvard to pay a professor of physics.

The local Cambridge and Boston doctors, including Dr. John Warren, had given a few lectures at Harvard up to this time. Dr. Cuming’s bequest and a couple of others made it possible to hire three physicians: Dr. John Warren, surgery, one for physics and Dr. Gorham for material medica and chemistry, and to pay them to lecture at a “branch” in Boston. Thus Harvard Medical became a reality and Harvard became a university, although the founding of the Theological School at about the same time seemed more significant to Josiah Quincy in his History of Harvard.

Dr. Cuming also left money to the Town of Concord and to the First Parish for communion silver. He deserves the grateful remembrance of us all. It was his custom not to charge for calls made on Sunday and one wonders if it wasn’t true that more people sent for the doctor that day than any other. He died in 1788.

Dr. Isaac Hurd came to Concord the next year, 1789, but without benefit of any formal medical education. He was born in 1756 in Charlestown, graduated from Harvard in 1776 when Harvard was in Concord, and commenced practice in Billerica in 1778 after two years with Dr. Prescott of Groton. He lived at the Block House on the Savings Bank site until his death in 1844 at the age of 88.

Abishai Brown had been captain in the Revolution and thus Shattuck says “acquired some skill in surgery and had considerable practice as a surgeon on his return to Concord.” He lived on the corner of Barrett’s Mill Road and Lowell Road in a house once used as a tavern, which has now been moved down Barrett’s Mill Road to the second house lot on the left.

Joseph Hunt, born in Concord in 1749, youngest son of Deacon Simon Hunt, graduated from Harvard in 1770 and studied under Dr. Cuming and went to practice in Dracut but his intellectual curiosity had been aroused and he was caught robbing a grave in Dracut for the purpose of dissection. He was compelled publicly to re-inter the body, go down on bended knee and ask pardon of the relatives and he left Dracut in disgrace. Back in Concord, he did not try to practice at first but taught the town school for two years and married Lucy Whiting, daughter of Thomas Whiting, fourth minister of the church. He was elected to the Social Circle and was an honored and respected citizen. As ill health made the practice of medicine hard, he opened an apothecary shop in his front room (now the Tweed Shop). And after his death in 1812 the business was carried on there by his widow and by Betty Nutting who had worked for him. His nephew, William Whiting, came to live with him and rode to Boston at the age of thirteen to bring back medicines in his saddlebag. The Whitings later had a successful carriage manufacturing business on Main Street and Academy Lane. Needless to say, Betty Nutting’s remedies were primitive by modern standards. Thoreau told of an eyestone, which she sold or rented out. If bound into an eye at night, it would travel around and remove any impurities.

Dr. Edward Jarvis, a Concord man who practiced here from 1832-1837, was more important in the history of medicine than in Concord’s medical history, for he soon went to Louisville, Kentucky, then returned to Dorchester where he specialized in the care of the insane, a field where investigation was very much needed. He followed Lemuel Shattuck in his interest in Concord history and in vital statistics and was called on to help prepare the U.S. Census of 1860. In his old age he wrote down what he remembered about Concord houses, a manuscript which is invaluable to anyone with an interest in early 19thh century history.

Dr. Henry Barrett, son of Col. Sherman Barrett of Concord, came to take the place of Dr. Isaac Hurd, living at the Block House. His practice lasted from 1845-1889.

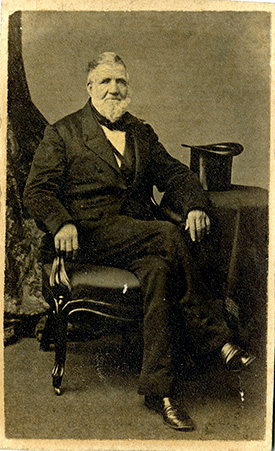

Dr. Josiah Bartlett

Others in his day were Drs. Gallup, Sawyer, Whiting and Ballou as homeopaths; Drs. Tewksbury and Dillingham as electics and some others, but the doctor of the period was undoubtedly Dr. Josiah Bartlett, whose downright character, outspoken opinions and faithful service made him a local character in the best sense. His practice extended from 1819-1878. Dr. Edward Emerson became his partner in 1873. Dr. Emerson gave up the profession in 1884 to devote himself to editing his father’s works, and Dr. George E. Titcomb took his place. Dr. Titcomb lived at 56 Main Street and then in the familiar doctor’s house at 7 Sudbury Road. Many of us remember him. He was in the outspoken tradition but was first to adopt new methods. He did not hesitate to demand good service when the first telephones were installed and once had his instrument disconnected because of his heated language to the operator. He must apologize, to have it put back in use. He rang the bell, picked up the earphone, and said, “Are you the girl I told to go to Hell? Well, you needn’t go.”

His early automobile was capable of terrifying speed. Once he was brought into court for some infraction. “That will be five dollars,” declared Judge Keyes. “All right,” said the doctor, “that is just my charge for your wife’s last confinement, Chief.” Then and there the Chief of Police settled up. Dr. Titcomb never thought of sending bills to half the town population. The calls were often never entered on his accounts. When the Emerson Hospital was opened, he performed frequent successful appendectomies, a new cure for what had been a fatal disease.

To speak of Drs. Braley, Hutchinson, Chamberlin, and ickard would bring this study to a point where others know much more about it than I do.

Abiel Heywood commenced practice in 1790 with a little office facing the lane which is now Everett Street. He was town clerk and justice of the peace and judge of the county court of common pleas. For years he was the town’s most eligible bachelor. He created a sensation when, at the age of 63, in his capacity as town clerk, he read in church the banns to his own marriage to Lucy Fay. He was so busy with his public duties that he virtually gave up the practice of medicine. He died in 1839 at the age of 80.

Dudley Smith, born in Gilsum, N. H., in 1799, studied with Dr. John Warren of Boston. He graduated from the Dartmouth Medical School in 1825, came to Concord the same year but removed to Lowell in 1832. You will notice that he was the first medical graduate of any college but Harvard and must have found it hard to find friends in Concord.

Dr. Josiah Bartlett was born in 1796, eleventh of the sixteen children of Dr. Josiah Bartlett, Sr., of Charlestown. He graduated from Harvard in 1816, got his medical degree in 1819, and started to practice in Concord in 1820. In 1821, he married Martha Bradford, daughter of Gamaliel Bradford of Charlestown and sister of Mrs. Samuel Ripley of the Old Manse. They had six sons and three daughters. He had many public honors, including his election in 1862 as President of the Massachusetts Medical Society.

His minister, Rev. Grindall Reynolds, wrote of him:

He was outspoken to the last degree, and did not know how to conceal any opinion or feeling, and yet left few or no enemies behind him. He was unlike any other man whom I ever met. His life bore on every part of it the unmistakable impress of his personal peculiarities, his personal feelings and his personal conscience. He carried on his mind and heart the history, the antecedents and the wants of the whole town. He had become a skillful doctor, not so much by any superiority of preparation or by any remarkable amount of after-study, as by original fitness, and by vast accumulation of experience, garnered and used by a broad and trustworthy common-sense.

At the temperance meeting in the vestry, Timothy Prescott said, it was easy to cry out against the habit of drinking, which he did not wish to indulge, while he clung to the filthy habit of chewing.” The doctor rose and said that if his use of tobacco induced anyone to hold to the use of rum, so help him God, he would never touch it again, and opening the stove door he threw his quid in, and to his death kept to his word.

Whether sick or well, whether the patient was rich or poor, whatever the weather, wherever he was called he was sure to go. He said often that only once in fifty years had the weather kept him from going to his patients and then his sleigh upset every two rods and when he changed to horseback, his horse floundered in a drift and slipped him off his tail. The last week, when he was hardly able to climb into his low buggy or to creep upstairs and totter down, he was up four nights, and on several days his horse was harnessed two, three, and four times as fresh calls were made upon him.

Yet with all his press of business he was not out of place in church a dozen times in twenty years.

In 1851, he encountered, while driving near Nine-Acre Bridge, the wagon of a drunken Irishman, and had his leg broken just above the ankle. From that hour to his death never a day passed that he did not have more or less pain, yet he went right on.

About 1832 he began to take a lively interest in the temperance cause and within fifty years the drinking habits of Concord have been wonderfully modified. He had to pay for his humanity. One night a bottle of some disgusting fluid was thrown through his window, destroying his carpet. On another night his apple trees were girdled, on still another the tail of his horse was shaved and the chaise-top cut to ribbons; and the doctor rode with the streamers flying and the stump-tailed horse to the shame of the persecutors.

He always drove at break neck speed whether on an ordinary call or taking a fugitive slave to Fitchburg.

Mrs. John H. Moore told me that when Dr. Bartlett helped her mother take care of a hired man who died of small pox, he said of the sulphur burning in the hallway, “We are getting enough of this now, we shall not need it in the next world.”

Perhaps a space in that next world is reserved for the present day doctor who is unable to drive a couple of miles on a summer evening to see a child with a high fever.