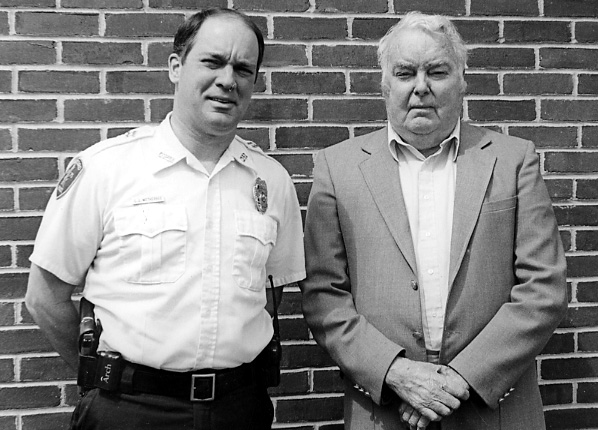

Leonard Wetherbee, Sr.

161 Hayward Mill Road

Leonard Wetherbee, Jr.

Chief of Police, Town of Concord

Senior, age 81; Junior, age 45

Interviewed ca. 1999

Concord Oral History Program

Renee Garrelick, Interviewer.

Leonard Jr. - I'm looking to have a police force that is professionally trained but responsive to the community. I'm also looking for the force to be reflective of the community and being reflective of everyone who phones, passes through, stops, or works here, so basically we've been looking to making the composition of the police department mirror society, not just the Concord community that puts its head on a pillow every night here. That has been a challenge.

I know the community because I grew up in West Concord. We had our own zip code, 01781. I'll never forget it. I very much know the community and for 45 years I've seen the changes in the community. That has had a great impact and influence on what I've done here at the police department.

We have 34 in the police department, and we have four from Concord. Each year when we have an opening and have applications, we receive basically zero applications from Concord. People in Concord are not inclined to join the police or fire department any more. That's one of the changes in the community. I'm not saying that's a negative change or positive change, it's reality. Our composition of the department I'm sure in a short period of time will be wholly from outside the community. That's a very big change because it used to be mandatory to live here. When it became very challenging to live here, the requirement was lessened. Now it's 15 miles from border to border, so from Southern New Hampshire out through Pepperell and swing it down and around Boston is the area we can pull from.

On paper the requirements today for the police force include being 18 years of age and a high school diploma. In reality, it is experience in a professional progressive police agency plus at least a bachelor's degree. That is also an area where we're working with the personnel department to formalize the requirements. We require a lot of people while they're here and we really have gained from them having prior experience and a strong educational background before they come.

Today the number of applicants can be huge for any opening. We had an entry level opening in the past where we were not looking specifically for people with prior experience, but those called lateralists, where they laterally transfer from another department, and the personnel department struggled through 500 applications for that one job. The personnel department narrows down the applicants, and they forward what they feel are the most qualified candidates in relation to the pool of candidates that we

receive.

My father started as a special policeman. We still have the title and we have just a couple of specials, but the way they are utilized are as different as night and day. My father will tell you when he came on, there was no training. He was given a gun and a badge and some clothing and told when to show up for work. It was all on-the-job training. As a special they would call you if someone was out sick or wanted the night off. They would bring in someone like my father to fill in for a shift. A year or so later after doing that, my father was offered a permanent position again without any formalized training. It wasn't for a number of years that he finally went to a training academy. It just wasn't done back then. It wasn't thought of and wasn't required. Today for an officer to step on the streets, they must have a minimum of 20 weeks of academy before ever performing any duties. So it's A to Z.

The type of training at the academy have even changed since I went through in 1978. The graduates going through the academy now are heavily schooled in community policing principals and procedures. They are heavily schooled in dealing with conflict resolution, domestic violence intervention, problem identification and problem solving. When we went through the academy, it was a lot of rote learning. You memorized chapter and section for motor vehicle law and traffic law. Certainly firearms and first aid haven't changed dramatically, the tools for both are a little different, but that's still there. The emphasis at today's academies is on community, while at the academy I went through it was basically we're the police, you're not. We'll learn here what to do when you call us. The minute you call us, we tell you stand back and we'll decide how to handle it. Now the recruits are taught when they receive a complaint for an issue, they problem solve with the complainant to try to address the issue. So they use a completely different philosophy, and it's very beneficial. People call us for everything.

I think I've been with the police department in an extremely special time. I came on in '77 and I was able to see the policing of old so to speak, and the tumultuous years during the '70s, what I call the flat line years in policing through the '80s and through the early '90s where we held onto what we were doing for decades even after the social upheaval. Kicking and screaming, we were dragged into the '90s. Then we started to become more open to this community policing philosophy. Then we were teaching old dogs new tricks. If you have a dog, it's a special dog that can learn a new trick. The old one will sit there and look at you for a while and when you turn your back, he's back to his old tricks. But now everyone we're bringing in, these dogs are taught from the beginning this philosophy. So there's been a great deal of change crammed into a couple of decades that I don't think we'll ever see in policing again. They were tough years and policing in general suffered in reputation through those years. I'm talking nationally.

One thing I should say is that now as I'm sitting here today as chief, certainly if it wasn't for my father and for his leadership and the principles instilled in me, I wouldn't be where I am today. I know that for a fact. The job was not that attractive when I was a kid watching him go to work at 1:00 in the morning on a snowy night knowing that all he was going to do for the next eight hours was walk in the cold in West Concord. He may warm up with the shanty man around the stove for a little while, but other than that it was a doorway or two. And in the morning that was it. When you're a kid, you don't really recognize things, but I certainly knew that we weren't wealthy. Now when I hear what my father took home for a week's paycheck when he first started, I make more than that in an hour, just to put it into perspective. It wasn't a glamorous job.

I went to school in the '60s and that certainly did not make policing a very popular choice. I went to Fitchburg State College to be a graphic arts teacher. After two years of that, I did not have my heart in it, and I left Fitchburg. I spoke to my father and told him I wanted to be a cop. I remember there was a blank look on his face. I think he was proud but he was also a little worried. Worried for a lot of reasons. He just said okay. He helped me along but he didn't push me. He would be supportive but he wouldn't interfere. I made a gazillion mistakes and he would be quick to point them out to me but he wouldn't interfere if I was going to be "brought up on the carpet" so to speak down here. Basically it was, you made a mistake, suck it up and go upstairs and take your medicine. Simple as that.

Very different than what we deal with now. Now I have a union rep and two union officials and "you can't ask my client that", it's a different philosophy. That's again why I think some of the ideals instilled in me are why I made it to the position I'm in today. Of course, timing is everything with some of the retirements, etc. that happened at the right time. It was very different. The union came in 1975 so it was here two years before I came in. Just about every place in policing in New England is unionized. Down South and out West they are not. They belong to the larger nationwide organizations, but not the local unions like we have.

The patrol officers start at $31,500 and it's a six step process. Within four or five years they are at $41,300. That's base pay. They also get 7% working nights, they get 25% if they have a graduate degree, 20% if they have an undergraduate degree, 15% for an associate's degree. And there is specialty assignment pay. Sergeants start at $37,500, but basically they are in the higher end of the patrol scale when they get hired, they're usually around $50,000 base, and then you put the incentives in. So it's a very livable wage. It's also such that it allows us to attract qualified candidates.

I was acting police chief in March 1993 and was permanent six months later in September 1993. I see the town from a very different perspective. The job requires me to be involved in the very things that are not my strongest points which is paperwork or administrative issues. That's why I wear a uniform. Prior police chiefs never did. When I spoke with the Town Manager, Chris Whelan, when we were talking about making this transition, I told him I really didn't want the job if I couldn't be a cop any more. He said I only want you to take the job if you promise to be a cop from this point forward. So it was a great match. I can still go out and do the job on the road from time to time when I can get out of this darn office.

There is more paperwork because there are more grant applications and more of everything. This is not something that has just crept up. It's exponentially been exploding in the last ten years. The state, local, federal requirements involving what we do and how we do it creates a great deal of a paper trail. Plus we've been involved in probably three-quarters of a million dollars worth of grants over the past 5 years and with those we also receive three-quarters of a million dollars worth of paperwork that goes along with the grants. That was something that was not only new to us but new to the town because we haven't really received funds from the federal government as far as law enforcement before. So there's a great deal of paperwork that is involved. The administration and the structure of the department are the things that have not changed. As a matter of fact, we have 1/2 of a clerical position less than we did when my father was here.

And since the 1980s we've had women on the police force. You'll notice the badge doesn't say patrolman any more. It says patrol officer. We have four women in the police department now, and we have one opening remaining and it could very well be filled with another woman. We've found that each time we've hired a woman, she was the most qualified candidate. The stereotypical reasons why we weren't hiring in the past have fallen by the wayside through reality. Women can do the job just as easy as a man. That's not even an issue any more. It's not something that's discussed. It's long been put to rest and for the good of the policing industry. In the early days, women had a rough time. The police department wasn't ready for them, and some individuals weren't ready to give up the male bastion of the building. There were some tough times for some of the early women here and everywhere.

Social issues have become an issue of the department where in the past they may have been looked at as somebody else's responsibility. Back when I first came on, it was sort of an unwritten rule when you received a phone call when you were at the desk, who else can handle this issue? It was thought of as a proper way to handle it. You've got this type of problem then call this agency, call this department in town, call this, and if you couldn't think of anything, you say sorry we can't handle that, that's a civil issue. That used to be the best way of dealing with noncriminal issues because we always thought of ourselves nationwide as crime fighters not sociologists. If it was civil, and even if it wasn't, tell them it was civil and send them off to a civil agency.

Now what we really focus on are quality of life issues. To me that's the greatest focus that we have here is improving the quality of life for the people in Concord. Certainly that might involve trying to reduce housebreak rates, rate of theft, etc., but that's only a part of it. If you have someone who lives in the inner city and is petrified because their child can't play on the playground, that they might step on a hypodermic needle or there might be some gang related violence that they might become a bystander to, so that person moves out to Concord. They move to Thoreau Street or to Laws Brook Road and now they have more of a fear because their child can't cross the street without getting killed in their mind by the traffic. The quality of life to them may even be a little lower than it was where they were before because they have much more of a fear for their child's safety. Now that's a whole different reason for it, but it's still a quality of life issue. So we get involved in family related issues and we get involved in neighborhood issues. We get involved in safety and engineering and planning and any other aspects of day-to-day life that we can use to become part of the problem solving initiative. Quality of life - that's the watchword.

I know the town so well since I grew up in West Concord but Concord has certainly changed and West Concord has changed. The great thing about West Concord is that Commonwealth Ave. is pretty much the same, which is great. I'll just use an example. I grew up in a three-bedroom ranch on Hayward Mill Road, and my parents still live there. Some day someone will purchase that home and they will raze it. It's a nice corner lot and they will tear the house down and they will build a much larger house on that piece of property. That's one of the ways Concord is changing. I guess economically in certain socioeconomic ways of looking at different neighborhoods, things are shifting. Plus a lot of the areas where we have neighborhoods in West Concord, they were fields and farms when I was a kid. Not too long ago.

I remember being on the school bus and we were going through West Concord and there was a big farm, the Derby farm. When I was in high school in the White Pond area, Stone Root Lane and Indian Pipe Road was a sand pit. Powder Mill Road was a dirt road with a one-lane wooden bridge. The homes at White Pond were mostly seasonal and now they've been built up as much as they can on the lots and certainly all year around now. You can almost take any street in West Concord and part of it wouldn't have existed. Hayward Mill Road, 164, if you just go up two or three houses into what used to be the Hatches house, where the pavement changes from peastone to regular tar, that was their driveway. It went up a dirt path up into the old powder mills and the saw mills up behind Nuclear Metals. We played around there. That was a huge backyard for us. It was tremendous. Now it's a large development. Literally almost every street has been extended. That's one of the reasons why policing in Concord has changed so much. When my father was on, they had three walking beats and two cars out on the road. We don't have any walking beats. I can't keep anyone down on a walking beat because they're always being called off. We always had 26 square miles but we didn't have the roadways in the neighborhoods that we do now. People want to see and they deserve to see a police cruiser through their neighborhood from time to time. It was easily done back then. Now it takes a lot more labor just to travel the roadways. Traffic has increased. The congestion and the request from neighborhoods to control the traffic has increased quite a bit.

We've done surveys and the highest issue that people in town have regardless whether their house was broken into, their car vandalized, or something was stolen was traffic. That's what impacts their quality of life. For us to deal with that, that means officers in cars in specific areas in the town. So the control pattern in the 23 years that I've been here is completely reversed from what it used to be. It used to be a depot beat 16 hours a day, the downtown beat and a West Concord beat. Of course, the downtown beat was up in the box directing traffic. That stopped just when I came on. We still had the box and we'd use it on special occasions, but it was pretty much phased out because they needed to put the officers in the cars. Plus truth be known, they used to tell you when you're directing traffic, when things really get tied up, get out of the box, and talk a walk and let traffic untie itself. It didn't help move traffic through town, it helped the pedestrian crossing and it helped a little bit with the traffic moving out of Walden Street which was a big problem. Plus the fire station was on Walden Street right there at Walden Street. This may be a guess but I think there is more pedestrian traffic downtown than there was in the past. Pedestrians allow Walden Street to empty all the time. It is the midwalk pedestrian crosswalks that stops traffic enough to let Keyes Road to empty, for Walden Street to empty, and traffic moves fairly well without putting an officer down there to screw it up.

In the beginning it was a negative for police officers to not be from Concord. I remember when we started to shift when I was still on patrol, we were getting officers from out of town who hadn't worked anywhere else and hired directly from the academy, there wasn't an ownership, there wasn't a feeling of belonging and you could tell it. You could sense it. Plus the community would let the officers know, where are you from? Immediately it was, "You don't have the ability to tell me, I've lived here for 30 years and you don't even live in town," so it was a confrontational issue. Now a lot of people have been in town for only a short period of time but the reason why we don't have the problems on the flip side is the officers coming out of the academies are wholly trained in the community policing concepts. They are here to adopt the community. They're here to solve problems. They're here to engage the community. The officers in the past and when I came on, everybody knew everybody. A lot of people sort of wax nostalgically about how good that was, but it was good and it wasn't good. We really push for equal treatment. Not baseless treatment but equal treatment and the officers aren't encumbered by having to intercede into a disturbance or a problem with someone at the high school or someone's brother-in-law or someone who's their next door neighbor. They're able to come in and get involved in issues without one side looking at the other and saying, there you go, these two know each other, they're involved here. That doesn't mean that they don't create relationships with members in the community. We really push for them to know people, but when they come in from the outside, that relationship is on a professional level. There is a respect from both sides and one is not going to try to take advantage of something that doesn't exist. That is very helpful in going about their jobs day to day. Now I think people really enjoy that. They enjoy the professionalism and the ability to come into a situation without having any entanglement from the past.

We recently contracted with an outside consulting firm, Crest Associates in Boston, to do a survey at random, a scientific survey, meaning the pool that we pulled from would have some statistical validity to it when we were finished and we wanted to be very objective. The survey was sent out and it was sent to residents by the firm, the results went back to the firm, and they've been destroyed by the firm. Only specific responses that people wanted follow-up from myself or the staff were forwarded. It went into all aspects of what we do and how people feel in their interaction with the department. We received some very high marks which we're very pleased with. But there were some issues that were brought up that are going to be very helpful to us in fine tuning what we're doing. It was very obvious that our interaction with people is limited. People are very pleased for the most part when they do interact with us, but other than that, we're somewhat faceless bodies that pass in the night so to speak. Plus they feel, and I'm using this term, we're doing a very poor job of communicating information to the community. It's the year 2000 and the ability to do that is here, painless and efficient and we've got to be ready to utilize not only today's technology but mouth-to-mouth and face-to-face technology. I think that is one of the strongest things that came out of the survey. People want to know their police more than they do now. They're saying yea, we're really pleased when we do get involved but we want to know you without having to be involved with you. We also want to know what is going on in town without having to ask for it. Those are two challenges that we're taking some long hard looks at how to deal with.

Today, we as a police department are involved more in programs with youth, but not as much as I would like to see. That was another aspect that was made very clear to me that the young people in town do not feel they're connected with the police department. We do do some things. I want to downplay that because I don't think we do enough. We're starting a new program, school resource officers, that will work primarily with the schools. In the past we had juvenile and youth officers but that was the negative connotation. That was when somebody got in trouble and these people came out and dealt with the person. We want people dealing with them on a day-to-day basis in a positive role. That's another area where I really think we need to get going. It's probably a negative of my having been here for 23 years and growing up in the community, I assumed coming from town and knowing the town fairly well, and the people in the administration in the school system, so I felt comfortable that there is nice connection there. Well, that's fine but that's a connection with me and with Elaine DiCicco and other school administrators, but the people who are coming and going don't have that. The other thing I really have to remember is that's a four-year period up there. You constantly get a new mixture of students every single year so every single year we've got to redouble our efforts with the new population to get involved with them.

The School Business Partnership has a program that the police department has participated in and the category of law enforcement is one of the largest areas of choice. I'm not sure how many follow through, but the program is great. We bring them down and they get the ride and they learn the communications. They're upstairs with the detectives, they watch me push some papers around for a little while. We try to really give them a full plate when they're down here to make it interesting for them. One of the initiatives we hope to have in the next year is a youth police academy. Some communities have citizen police academies and that's mostly for communities where there has been strained relations so that people from the community can come in and actually see what the police go through in their training and why they respond in certain ways. I'm looking to open it up to the younger, much younger population and let some of the young people in town come in and see what the job is like and receive some instruction and get hands on interaction. But the strength of that is we have 30 people go through in a class. The six or eight officers those 30 people are going to interact with are going to know them by first name and hopefully that will be a long time period that that bond will stay there.

The court certainly has changed. My father can tell you some rather humorous stories from when the court house was down where the Town Manager's office is in the hearing room at the Town House. Judge Whitney and Judge McWalter were local people dealing with the local people. Our court now consists of six communities. Since Judge Eaton retired, we really haven't had someone that comes from the community and lives in the community. Judge McGill has moved to the community which was a great asset, but he has moved on to a different assignment now. So that piece of the whole puzzle has sort of changed. Plus we're dealing with people from all over the country now. The level of interaction we're dealing with is greater and less community oriented. That's one thing that has sort of gone backwards is our direction of the court system. Now it's a very busy, very impersonal part of the system. That's not the fault of anyone who is involved in it, it's the fault of volume. So the court system has changed.

The system changing is not so much an interference as something that removes from the table four or five options of being able to deal with something. It will leave you with just one. Where basically when they move to a certain point, you're locked into a certain point and then you have to go down to court and work it out down there. So that aspect of it creates a lot more involvement by attorneys. It's not a bad thing. It just changes things. It changes the way we interact. As a matter of fact to try to deal with that, we're just starting a restorative program in Concord to try to train the community, a certain group of people in the community, to deal with cases that we don't bring down to court, mostly with younger people as an alternative to the system so to speak. It will try to give the community a seat at the table so that we don't allow victims to remain victims. Whether it's their lawn was damaged or some vandalism or spray painting was done, they're able to face the person, mostly a young person, and explain this is what you caused me, and let the community decide how to deal with them. That's restorative justice.

Another change has been communication. In my father's time, he would go out without a portable radio. If the station wanted him, they'd call the shanty man and he'd put a lantern on the gate, and when he walked around, he'd see the lantern and go get the call and vice versa. West Concord was different back then. We have lounges now, but then there were bars in West Concord. Friday night walking the beat could be interesting breaking up fights. If you had to bring the person in, you had to drag them down to the shanty man and he could call, or bring them to a phone somewhere, get someone's attention and get a car to come up and pick them up. That is unthinkable right now in any aspect of policing. You don't go anywhere without communication. The first radios they had were huge. They were like Geiger counters. They were huge things with handles. The battery was three times the size of the radio. Now it's the size of a cigarette pack. Every officer that goes out has a cell phone, a pager, and a radio plus the cruiser is completely different. I remember when they used to take regular sedans and take tail lights and mount them on the roof. That was the red and blue lights for the car. That was just a mode of transportation back then. It's an office now. It's linked by a CDPD cellular modem to the station which allows the officer to replicate as if he were sitting in the communications center linked to all the state and federal computers. They can receive their calls over the computer, they fill out the reports on the computer, they access registration records, criminal records, wanted records from the cruiser. We have been looking at and probably will have very shortly small video cameras that will record everything they are doing for the officer's protection. We're really just scratching the surface of the technology. We expect to see in a short period of time that if you stop someone and your federal computer tells you that this person is wanted in Chicago for a certain crime, they can actually have that person put their thumb on a scanner, and it will immediately tell you if you've got the right person. That'll be here tomorrow.

Where we've come in seven years has been mindboggling, but prior to that we went from 1992, 1993, or 1994 you had to go back to where you had a radio in the car, then you had to go back 40 or 50 years before there was a different change in technology and that was the two-way radio, then go back another 10 years when it was just a one-way radio. You see in the movies, "Calling all cars, calling all cars," well, that was only a one-way radio. Back in those days, when you got your gun and badge, you got your call box key, and you'd go down and call the station and the light would go on on the top of it and you would see what they wanted and that type of thing.

When we look at communications, the next thing we're looking at is reversing the way we communicate with the police. That is now a central answering point for emergency calls. What we're looking at is gaining technology to reverse that where we can be the point that gives out all the emergency information through a computer link with a telephone communication system. That will allow us through a database or using a GIS map to outline a certain area, record a message, press a button and everyone in that area is called and that emergency message is given out. I remember in the '80s when there was a gas leak over at the Grace Company in Acton, and all up around Branch Road we had to evacuate those people. We were walking around, knocking on doors, telling people either get inside and stay in where you don't have any outside ventilation or quickly get to the high school because you can't be here with the outside gases at a very dangerous degree. I'm breathing it walking house to house telling people you shouldn't be here, and we had headaches so bad that we couldn't go around any more. So we will be able to notify people in certain areas where it is dangerous to be in or where you need to tell a great amount of people in a short period of time a certain message. Things are fiscally tight right now and thanks to the Concord Business Partnership and the business members in the community, it looks like it's going to be a reality in the spring of the year 2000. That's another really great example of how the community connects with the police department, problem solves, recognizes an issue and the community comes up with the solution. In the past it was always we're the cops, we'll tell you what's wrong and how to fix it. So it's an obvious example of how we're benefiting by being part of the community rather than being apart from it.

This all came about because I was asked to speak at one of the Concord Business Partnership breakfast meetings, and I met with Renee Garrelick outside the Colonial Inn and the night before there was a power outage which really severely impacted the members of the business community never mind some of the households in that section of town and out north towards Carlisle. So I was basically asked how do we know especially when we're depending on electricity for restaurants, etc. when the power is going back on. What is the best way we're going to get that information? My answer was I don't know. We don't have a good way to get you that information because the light department is out busy trying to fix what the problem is. So calling the light department really can't help you and at the same time, everyone is doing the only thing they know what to do, and that's call the only people that are answering the phone after 4:00 at night and that's the public safety. So the phones in the public safety department get completely jammed, and we're unable to give anyone any information, never mind we're not able to say this is what the problem is and this is when it might come back. We can't even tell you when to call back. We can't even tell you how we're going to get you that information. You've got to remember there are a lot of people on ventilators in town, on certain machinery that's necessary for their medical well being. A lot more than people realize, and it's imperative they understand when these issues are going to come up.

I remember we had a major outage six, seven years ago the day before Thanksgiving. A power station blew in Lexington and the whole feed coming into town was gone. For four solid hours, every single phone line was jammed and we couldn't get emergency calls, we couldn't get anything because people were in a panic. As nice as we could, we told everyone we didn't know when it was coming back on. Our ability with something like this will be to record a message, send it out, and also tell people if you have any questions, if it hasn't come on in an hour, here's a number where you can call, and we continually update that number. So people won't be calling back in. This will dramatically change the way we're going to interact. And not to belabor a point, but I think it's a perfect example of how the business community, as part of the community, is feeling comfortable with problem solving on an issue that affects both, and it was the business community that came up with the solution. Leonard, Sr. - I came to join the police force by accident. My wife and I were downtown at Snow's Drugstore one night and the then chief came in. He said he needed officers and wanted to know if I would be interested. I said, "No, but I'll think about it." And as it turned out the following night we were in the same spot and he came in and said, "You're going to be a special. Come down to the Town Hall tomorrow and get sworn in." And that's how I got on. This was around 1961.

There were a lot special policemen then. They worked regular shifts if somebody was out sick. They used to work a lot of road jobs and whatever came up. My training then was zero. The first time I worked the shift, I came into the station, they gave me a gun and a badge, and put me on the street. That's it. You learned as you went along. Much later they started sending people to state police academy which I went to along with others in the department. It's mandatory now before you can even get on the force.

When I first came on, the police station was right where it is now. There wasn't much to it. They had a range off the garage, and the chief's office was downstairs. There was very little room to tell you the truth. Before they built the police station, they used to practice in the basement of the Town House.

When I joined the force, you had to be a resident of Concord. I think there were about 28 to 30 people in the department including the specials. Everybody came from Concord. A fellow had a son who was in the fire department and he got fired because he wasn't living in Concord. Several people were really upset over that. A couple of the citizens wanted to pay the lawyer's fee and everything else to fight it. But he said, if they don't want me, I won't stay.

Then you knew everybody in town. At that time several of us used to get in the habit of just going around, and if we saw somebody working and you didn't know them, you went in and introduced yourself to them. You met a lot of people that way. I can never remember anybody getting perturbed because you stopped and spoke to them. Most people really liked it. You could go downtown and you knew everybody on the street. I remember Dr. McDonald had an office downtown, and he'd come out and come over to the box if you were directing traffic and say, "You're doing a fine job." There was a lady and I can't remember her name but she used to wear white mittens in the winter time, and everybody got a pair of those white mittens that she made herself. You looked forward to them. They were really nice.

You saw the town in a very special way being a policeman. Some of the stuff you saw, you didn't like, but it was your job and you had to take care of it. On the whole you enjoyed it. It's a lot tougher today than it was in those days. You always had somebody around that you could talk to. I remember we used to walk the beat midnight to 8:00 and there was a minister in town and he'd come down and walk around with you. I said to him one morning, "What are you doing out of bed this time of morning?" He says, "Oh, I couldn't sleep so I figured I'd come down and take a little walk with you."

Most of my beat walking was done in West Concord. Low man on the totem pole was the man that walked the beat. You came to work at midnight at the station and a cruiser would give you a ride to West Concord. The guy would dump you off and say see you at 8:00 in the morning. And that's where you spent the night. Sometimes funny things happened. I remember one night I was walking up around the Colonial Motor garage, and at night when you walked, you were supposed to walk away from the building. Well, I was in a hurry that night and I walked right around the corner, and the first thing I knew something had hit me in the legs just about knocked me down. It was a big collie dog going the other way. My beat consisted of Commonwealth Avenue down to the Plymouth garage across the street over to Soberg & Edwards Gas Station and the lumber company in behind. You shook the doorknob on every building. Then on up to the library and the church across the street, Our Lady's Church and down Main Street to Carter Furniture, and all the way down to Baker Avenue. There was a couple of buildings in there at the time that you had to check. One night in the wintertime, I was going down towards Soberg & Edwards, and there was a boat shop where the restaurant is now across from the bank. I looked and I thought I could see a broken window. I went over and took a look at it and there was snow piled up against it. I walked around to the side of the building just in time to hear a car taking off up the street and they had this big outboard motor on a rack, ready to load it and go off with it. At that time you had no radio. A car comes down the street, so I stepped out in the street and stopped the guy and told him to stop up at the shanty and have the shanty man call the station that I may need some help, which he did. Poor old guy was scared half out of his wits when I stepped out to stop him. There were a lot of things that happened like that.

One time I just got there and I checked a few buildings right in the area of the railroad shanty, and the shanty man come out and we were talking about the weather and so on, and down the street I see two or three fellows come out of the Plymouth garage. So I ran down the sidewalk staying in the shadows, and I got down to the 5 & 10 and I stepped out in the street and said, "Hold it." They stopped and said, "What do you want?" I said, "Where are you coming from?" They said, "Down on the side street down there. We stopped to see a girl." I said, "Who's the girl?" They gave me some wild name that I didn't know. So Sal Silvio who lived there at the end of the street was at the station, and I called him and I asked him who lives in the third house up across from him on the right hand side. He said, "I don't know. Some woman just moved in there. I don't know who she is." I had a holster at the time that to take the gun out, you had to press the button. Well, I pressed the button and I was holding the holster and I had the portable radio in my hand, and I noticed one guy never took his eyes off my hand with the gun. I was saying to myself there's something wrong. So I called the station and asked for some help, that I had three subjects up here that we've got to check out. Sal says, "I'll be right there." And I look up and the three of them are gone. I called the station again and told them these three guys took off and ran over toward the lumber company. Sal comes in from Commonwealth Avenue and he called, "Hey, get over here. Is this one of them?" They had a car in there. I looked at him and said, "Yea, that's one of them." So Sal says let's shake this guy down. He takes his hat off. Sal says, "Take the jacket off." The guy says, "It's cold." Sal says, "Take the jacket off." We got it off him and he's got a straight edge razor down the back of his pants. So Sal says, "That's it, fella, everything comes off." He says, "It's too cold." Sal says, "Everything." We made sure he had no more weapons. We had him put his clothes back on and we handcuffed him to the car. The car was loaded with all kinds of stolen stuff. Come to find out they had a break-in up at the International Harvester tractor place on Route 2A and they were missing $500. He had the $500 in his pocket. The other two guys seemed to disappear but we knew we had them blocked in because to get across the river they had to swim. At that time there was a state cop working extra duty at the Concordian Motel, and he had a radio and was listening. We had other state police come in and Maynard sent a car down and Acton sent a car down. Pretty soon the guy from the Howard Johnson's called the state police and says, "I've got two guys who want a taxi right away. Can you send one down?" In about three seconds there were all kinds of cruisers there.

We got them down to the station and then we found out they had broken into the International garage, but we couldn't get any background on them. Bill Boland was a FBI agent who lived in town, and the chief called him and asked him if he could come down and see what he could find out. Well, he did and he got on the phone and called his main office. When he hung up he says, "Sit on those guys. One is doing life for murder, the second was doing 20 years for attempted murder of a police officer, and the third one is just a punk." They had broken out 12 years before from the West Virginia penitentiary. One of them had a Virginia drivers license. The police department was requested to send his license back because when he got out he'd need it. He got out about three weeks later, got into a battle with some New Jersey state police, and got shot and killed.

There were more bars at that time in West Concord. There was a place down where the 5&10 is before LaHiffs was there. That was a busy place on Friday night if you worked the 5:00 p.m. to 1:00 a.m. shift. There was something going on there all the time. They had more brawls than you can shake a stick at. I can still see Jim Alexander going in there and hauling a couple of McHugh boys out. They were fighting among themselves. It was funny.

I worked under Chief Costello who introduced the Police Blotter in the local paper. He obviously wrote it, but the Police Blotter is something different now. Leonard Jr. - The Police Blotter is computer generated and is the exact record of our involvement over a 24 hour 7 day period. My ability to tell the public that this computer generated log cannot be tampered with, cannot be changed, and is an accurate representation of what we have done, the people we have had contact with, all of our activities is something I think the public needs to feel very confident in. It's an accurate record and not one that is reflected in a personal way. It doesn't have the ability to be changed or recorded in a different manner. I think it protects the town and the police department from any accusations of adding, deleting, slanting, changing, etc. I'm really very hesitant to be involved in any one-sided reporting from the department to the public. I'd much rather have the newspaper decide what items they want to run, and then I'm glad to answer any questions they may have.

When I first started on as chief I was receiving a number of queries such as can you keep this out of the log, so and so was arrested last night and we'd really appreciate it if you'd keep it out of the log. There were some people frustrated and angry when I told them no, I cannot do that. It's a public document, a sacred document, and it's not one I can alter. I told them they would have to talk to the editor of the Concord Journal as to what they decide to put in, and I don't have and will not have any input into that. That kept up for a while, but I'd say in the last two years I just don't get any calls any more. Everyone seems to understand and accept that. So the flurry of calls in the beginning made me think, why would everybody think I would or could change the logs? Some presidents get into trouble for things like that. I'm not going to be comfortable altering Concord's history. That police log should be an accurate log of Concord's history.

Leonard Sr. - I was on the police force 22 years from 1961 to 1983.

Leonard Jr. - We overlapped for about 6 1/2 years and I only worked on the same shift with him two or three times in that whole time period. It was great being in the same department. The time we did work together, he was never shy about pointing out areas I needed to improve on, but at the same time as I said, I think the concept of community and staying in contact with people in town, and not going toward this model of distance or impersonal policing, luckily I think I held onto those ideals because that's exactly what we're trying to do right across the country today. Keeping close contact with the public and allowing the public to have input into what we are doing and problem solving with the public. Letting the cops and the people in the community feel comfortable knowing each other.

Leonard Sr. - Today there are more career choices when you go into being a policeman where in my time there were fewer choices. I always said a police officer back then including myself couldn 't make it today. We wouldn't have the education and so forth that's needed. Every one of these people in this department with very few exceptions have college degrees, if they haven't all got them. Most of them have master's degrees.

You know I heard a conversation years ago asking a guy why he wanted to be a police officer. He came out with the answer, "I like to help people." And he was abruptly told you're full of baloney. The only thing you want is a steady job. For some reason back then it was only a job that was available where today it's more of a career choice.

Leonard Jr. - When I first came on, the comment was great, you got stability, you got job security. The average person now changes jobs seven times in their lifetime and in my dad's generation, people latched onto a job whether they liked it or not and they carried it through for the rest of their lives. Early on people were saying, well, you had some turnover. Well, yes. I take from small departments, large departments take from our department, people move around. They're not born here, they're not brought up here, we do try to instill a sense of community but they're looking at a career, and in a career you make decisions based on what is beneficial to your career and that's why people move around in law enforcement where they never did in the past. It was unheard of for someone to leave one department and go to another one.

Leonard Sr. - The thing back then was how many years do you have to go before retirement. Nobody ever quit.

Leonard Jr. - The other thing is I think we hold a very high standard now, professionally and ethically, on all counts. We're not afraid of suggesting that someone might find another career choice. I was asked this by a member of the board of selectman once about turnover, and I said well, some people have blessed us by coming on the department and some have blessed us by leaving. I feel very comfortable in the people we've hired and the people who've left. I think each coming and going has incrementally made us a stronger organization. I'm not afraid to suggest to someone that maybe you might think of something else for a career choice. That's was never done in my dad's day.