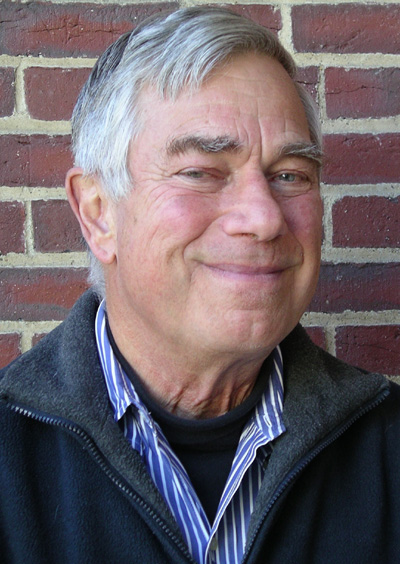

Henry Vaillant

Interviewer: Michael Kline

Date: November 13, 2013

Place of Interview: Concord Public Library Boardroom

Transcriptionist: Adept Word Management

Click here for audio.

Audio file is in .mp3 format.

Michael Kline: 00:00:00 My name is Michael Kline. We're here this morning, November 14th, 2013. I'm here with Carrie Kline in the Boardroom of the Concord Free Public Library, a beautiful, crystal, very cold, sunny day outside. And would you please introduce yourself? "My name is—"

Michael Kline: 00:00:00 My name is Michael Kline. We're here this morning, November 14th, 2013. I'm here with Carrie Kline in the Boardroom of the Concord Free Public Library, a beautiful, crystal, very cold, sunny day outside. And would you please introduce yourself? "My name is—"

Henry Vaillant: My name is Henry Vaillant.

MK: And your date of birth?

HV: Is December 17th, 1936.

MK: Would you mind—to begin, tell us a little bit about your people and where you were raised.

HV: I went to 7 different schools in the first 7 years of my schooling, so I'm not exactly sure where I was raised, but I was born in New York, lived in New York and then Philadelphia area, and during World War II, my father was assigned to the OWI, and the family lived in Lima, Peru.

MK: OWI?

HV: Office of War Information. It was the predecessor of CIA. And we were—we lived in Lima, Peru, until 1944. We returned to Pennsylvania. My father died suddenly and the family, my mom and her 3 kids, moved to first Connecticut and then New Hampshire. So I really spent most of my childhood in New Hampshire. I was fortunate to go to Harvard College and Harvard Medical School and become introduced to Massachusetts. One of the very first dates that Janet and I had was coming to Walden Pond on a wonderful day, such as this, only it was a little later in the winter. The ice was solid, snow had fallen, and we walked across Walden Pond—damn fool thing to do at the age of 18—but that was when I met Concord, and I have to say that the chance to live here has been a wonderful opportunity.

MK: 00:03:01 Can we back up just a little bit, ask you your parents' names? Tell us a little bit about your other siblings?

HV: Sure. My mother was named Mary Suzannah Beck. She was born in Mexico City to Eman Beck who left his small town in Indiana to seek his fortune in Mexico. He was first an overseer on a plantation and then a banker and real estate person in Mexico City. This would have been at the end of the 19th century.

Carrie Kline: Sorry?

HV: This would have been at the end of the 19th century.

CK: Okay. And can you spell Suzannah and Eman for us?

HV: Sure. S—U—Z—A—N—N—A—H. Eman, E—M—A—N.

CK: So we're back at the end of the 19th century.

HV: And he—my mother was born in 1908 and grew up in Mexico City. It was the custom of my maternal grandparents to entertain visiting scholars when they came to Mexico City, and my father came to Mexico City as a young archeologist to excavate Aztec ruins around Mexico City, and he was brought to my grandfather's house to be welcomed, and he saw my mother down—coming downstairs and declared to himself, "That's the woman I'm going to marry."

CK: What was his name?

HV: His name was George Clapp Vaillant, and he went on to a distinguished archeological career, focused primarily on the Aztecs but also the Olmec and the Mayan pre-Columbian civilizations. The Peruvian experience was significant because, of course, my mother was bilingual, having grown up in Mexico. My father spoke atrocious but hilarious Spanish, which he had learned during his archeological excavations that involved supervising a number of Mexican workmen to do the heavy digging and lifting. The influence on me was enormous, in that interesting people came to the house, and you never knew exactly what was going to be expected of you. Once in Peru, Yehudi Menuhin, the famous violinist, came for a concert, and my parents received him because—although my father was in the OWI, his cover was Cultural Attaché in the American Embassy. So we—they politely received Yehudi Menuhin who, having heard that I was taking piano lessons, insisted on hearing me play. (laughs) Poor man, poor man, I was not a—I was not a musician. And my older sister, Joanna Vaillant Settle, married Ellis Settle, a poet and—well, I guess the right term is a 19th century term—man of letters, meaning he wrote much, published little. My brother, George Eman Vaillant—you have the spelling of Eman—was a very prolific writer and has published a number of books about adult mental health. And my initial career was going to be in public health. I have a couple of medical issues that made it necessary for me to live near really good medical centers, and I was lucky to find a post with a small medical group called The Acton Medical Associates in 1970. At that time in Massachusetts, group practice was thought of as kind of a socialistic activity, and when I joined the staff of Emerson Hospital, the other doctors looked at us a little bit askance because we were a group practice, not the good individual solid practitioners that everybody was used to. The staff was small, there were probably thirty-five members, and we—our information system was everybody had a little light—had a little light in the hospital. And he turned it on when he was in hospital, turned it off when he was out of the hospital. The telephone operator sat in the front hall, and she had a mirror, so she could answer the phone, look at the mirror, see whose light was on, and she somehow learned mirror reading, and then if they wanted you, she'd page you—overhead page—and it was as simple as that. It was a wonderful system.

MK: 00:10:24 Efficient.

HV: Right. Infinitely preferable to being beeped or Bluetoothed or whatever else is currently in use. I think the most interesting town-of-Concord experience I had in the beginning was, I went down to the townhouse and filled out—I can't remember if it's a blue card or a green card—but new residents are encouraged to fill them out, say if they'd be willing to serve on any committees, what their skills are, and so I filled out a card and said that I was on the faculty of the Harvard School of Public Health, which is where I started from before I came here to practice. And, if you can believe it, the Concord Town Meeting that spring had passed a resolution that said that salt was not going to be used on the roads any more. This was because of Concord's love of nature and because concerns were beginning to emerge for the first time that, you know, just throwing pesticides and salt and chemicals of various kinds around was not altogether a good idea.

MK: This was in—?

HV: This would have been in the spring of 1970 that this ordinance was passed at Concord Town Meeting. So (laughs) the Concord Highway Department began to try to take care of its roads without salt, and, as luck would have it, it was a frigid winter with quite a high snowfall and occasional melts, (laughs) so that the Concord roads became ice skating rinks. The Town Meeting had stipulated that there would be a commission to oversee this, and, as luck would have it, I got named to the commission. Fortunately, (laughs) another man was on the commission, John Boardman, who was a contractor, stone mason, and a very well—educated and literate fellow, and he and I bonded on the committee because we realized that trying to keep roads safe without salt was a fruitless and altogether blockheaded operation. So, somehow or other, we were able to get the town to buy these spreaders that were made in Sweden that combined salt and sand in the ratio of salt and sand that would get the most out of the salt, it would adhere to the sand, and the salt and the sand as it was driven over would chew up the ice and get down to hard pavement, and that was a way of compromise that worked out to everyone's benefit.

MK: 00:14:56 How did you—you described the messaging system at the Emerson Hospital—tell me more about how the hospital was then and how the town was then.

HV: Well, the town wasn't that much smaller than it is now. I don't remember exactly what the population was, but as Casey Stengel said, you could look it up. The—but what was different about the hospital, at least from today's viewpoint, is that it was a cottage hospital, and a cottage hospital was a small hospital that operated primarily by general practitioners, primary care physicians, and only a few specialists. We had some general surgeons, we had some obstetricians and gynecologists, and we had orthopedic surgeons. We had pediatricians and a couple of nose and throat surgeons because in those days, they did a lot of tonsillectomies. But there were no cardiologists, there were no pulmonologists, there were no full—time plastic surgeons or vascular surgeons, or any of the specialties. So that when things went wrong or were complex, patients went to town. The—therefore the board of the hospital, which then was made up almost entirely of Acton—I mean, sorry—of Concord and Lincoln folks, had what I'm afraid I considered to be somewhat provincial point of view. They believed that the focus of the hospital should be strictly on its immediate local area. Since I was involved in a group practice in Acton and we were interested in getting people from all adjacent towns to come to us, we wanted to have a hospital that would welcome people from outside the fold and would have input. This meant eventually that the board conceived of the twelve—town rule. Emerson would take care of 12 towns around it. I couldn't possibly tell you exactly what they were, which towns they were, but it represented an enlargement of scope and an enlargement of thinking, and it also meant that some of the board members would be sought from those outer towns, lending a valuable perspective. I once heard an Emerson board member say, "Well, why should we raise much money for the hospital, you know, we want it small, and, if there should be a deficit, well, the board members would just cover it out of their own pockets." This was not probably the most realistic point of view as—because the technology of medicine was changing very quickly and the hospital, which didn't have an intensive care unit when I joined, soon began to enlarge both its—both its size and its facility—facilities and its medical staff. And the other thing that I think was advantageous is that we began to forge alliances with in—town hospitals, experimenting with different hospitals, but finally joining the Partners Medical Group.

MK: In—town means in—?

HV: In Boston. In Massachusetts, people tend to look east for medical care. (laughs)

MK: Well, you—you brought up—you brought an amazing background in public health to this small—town, small—minded hospital. Were there other—were there other people who had that orientation?

HV: 00:20:44 Yes. And we—(laughs) the best way I can put it is initially there were probably about 5 of us who thought broadly. There was a wonderful man from Bedford named Kenneth Kaplan who died untimely but who always looked at the bigger picture of what a hospital should be and always upheld the highest standards.

CK: Kaplan with a K?

HV: With a K. Kenneth also with a K. And my colleagues from Acton Medical thought in a larger scheme. In fact, one of them, Jim Longcope, who eventually rebuilt himself from a general practitioner to a psychiatrist, had an enormous varnished map of the whole area, approximately the 12 towns, and when new patients came to us, we would stick pins in the map (laughs) to see where they came from. And then we would feel very happy if we saw a bunch of pins coming together because that meant that people had sent their neighbors to us. I was told frankly, when I first opened—when I first came out into practice—that I would not succeed because there were too many good internists already and that I had allied myself with a group that was too leftist in their views. Imagine, group practice, leftist. But such is, such is history. So the transformation of medical care is one of the biggest changes. There are now virtually no physicians in solo practice. All are in groups and many are actual employees of a hospital or a larger system. So in fact, the profession has been transformed into a—well, into a skilled—into a skilled labor force, but a labor force that is under control of management, government, and other regulatory forces. It's hard to conceive of the freedom that an individual practitioner had in 1970, and overall—

MK: Could we wait? I think Carrie's going to try to do something about the—

HV: Yeah, we've got—

MK: Okay.

HV: I think one of the important forces that brought about change in the 1970s was the institution of Medicare, which really began actively in 1966, but whenever there are changes in medical insurance, the first one being Blue Cross—Blue Shield, which came about in the late ‘30s and ‘40s because the factories had the wages frozen by the war years, and they were wanting to compete with each other for good workers. So the way they competed was to give medical benefits and very, very generous medical benefits. And since the workforce was relatively young, it wasn't that expensive, and many of the models for gold—plated insurance plans were formulated by unions like the United Auto Workers who negotiated these absolutely wonderful medical plans. Fast forward to 1965—66, when Medicare came and offered health insurance to folks 65 and over, the effect was to enlarge the market and the demand for good medicine and the wonderful medical procedures that were being made possible, space—age hips and so forth. But the conservative elements of the medical profession and a lot of other places as well had, even in the early ‘40s, had called Blue Cross—Blue Shield socialized medicine, they called Medicare socialized medicine, and right now we're in the middle of a name—calling match over the Affordable Care Act. So these are the cosmic forces that bring about professional change, and I think a lot of hospitals in the area reacted just as Emerson did, which was, they changed. The hospital enlarged, saw itself as a regional medical center, not as a cottage hospital, and practitioners began to form groups such as ours, and the whole attitude of my fellow professionals, which used to be, when I began, "Gee, why are you—why are you doing this?" became not "Why are you doing this?" but "How do you do it?" Because imitation, they say, is the highest form of flattery. But I want to talk a little bit about living in the town—

MK: 00:28:58 Yes.

HV: —as a citizen. Because, going back to snow again, one of the great adventures that our family had was the blizzard of 1978. And schools were closed for three weeks, roads were closed for 1 week, and miraculously telephones and power lines were not down. So, I remember the experience of our family because we were all—altogether now in three feet of snow, and the children built these wonderful forts and tunnels, and—

MK: Where were you living at the time?

HV: We were living up on Annursnac Hill.

CK: Spelling?

HV: A—N—N—U—R—S—N—A—C, Annursnac, one word, Hill, another word. And, so the children would find ways to play, and the adults would find ways to cooperate. I couldn't get—I couldn't get to my office for three weeks. I did get to the hospital of course. There was no way out. (laughs) I had to use snowshoes and hitch a ride on a snowplow. But one of the things I remember doing is the neighborhood organized a telephone network, and the network looked in everybody's medicine cabinet to find unused supplies of antibiotics, so kids with earaches or Strep throats or suspicion of same could obtain antibiotics even though nobody could get out and about. And it scrolled back to an earlier era. And it was—it was a special time for us and kind of a milestone in our life in the town.

I think other things that I would point to: Later on I was on the Board of Health for six years in Concord, and some interesting things happened there. The first one was a company called Nuclear Metals that was in West Concord and was occupied with using spent uranium, which is very heavy but does emit some radioactivity. It was involved in recycling spent uranium for two uses: One was to add weight to armor—piercing shells that were used in the military, and the other was to use this as shielding in many of the x—ray delivery devices, or delivery devices for x—ray therapy. And initially the company was independent, really expertly run by a board of MIT professors, folks who had been involved in all kinds of World War II operations, but—so that they understood both manufacturing, science, and also the dangers of radiation. Well, as time went on, the factory was sold. And it went from one company to another, and the supervision became more and more lax. So then the town became preoccupied, and there was a slow but gradual evolution to making Nuclear Metals eventually a Superfund site and getting it properly cleaned up. But again, that was an interesting historical trend because, in the beginning, when I first came into practice in 1970, Nuclear Metals was thought of as almost a model industrial operation. People used to get blood counts every six months, they had a doctor on premises once a week, and then this all faded away as corporate pass—ons began, and then it was necessary for citizens, town, and state and federal to step in.

Another interesting Board of Health experience (laughs) was when a beaver dam resulted in interference with the West Concord septic systems of a number of newly built, and frankly rather pricey, houses. And there was an absolute uproar because all of a sudden it was spring floods, the people's backyards were stinking, their toilets weren't flushing, the Board of Health was supposed to do something. But we were checkmated by the wildlife conservation people because everybody loves a beaver. (laughs) And the resolution was happily decided by Mother Nature who came along with a big thaw at just the right time and solved the problem.

Then I think another Board of Health story was the Trinity Church, the Episcopal church, had a—had a garden that they were building that would be used for the ashes of whoever at Trinity Church wanted to have their ashes buried in the garden. Well, it happened that one of the neighbors became a vociferous objector because they were concerned that the remains might contain nuclear residue from treatments that the person had received in the last year of their lives, and there were some very interesting hearings on this subject in which (laughs)—in which I was pilloried because it was said I had a conflict of interest because I happened to be a member of Trinity Church, and therefore I would not mind its neighbors getting nuked. Of course, the—any radioactive substance that's used for medical diagnosis has a very short half—life, so by the end of two weeks, it's virtually all gone. But the concern remained.

MK: 00:38:46 Did you testify to that effect?

HV: I did. And the—

MK: But it was jaded testimony, right? As far as the neighbors were concerned?

HV: As far as—as far as a couple of them. They, you know, they thought I was a shill for the (laughs) for the Trinity Church. So I've used my 45 minutes I think, and—

CK: Only 39.

HV: Only 39?

CK: (laughs) If you have more, this is great, gem after gem. (laughter)

HV: Well—

CK: (???) (inaudible) 00:39:33

HV: Again, let me tell—let me tell two other stories. And they concern the emergency department of Emerson Hospital.

MK: 00:39:48 And the year?

HV: And the year, well, first one—the first one I'll tell—probably about, it would be about 1975. In those days, when there was an emergency at the hospital, or when somebody came in to the emergency department, there was a doctor on call, and he or she, wherever they happened to be, would be telephoned and told to come down to the hospital and see the emergency. And each day—every day a different member of the staff would be on call. And it didn't matter what your specialty was. So you might be called for nearly anything. Well, on this particular occasion, I'm called because there's a woman who is very dehydrated, has food poisoning, needs to be admitted to the hospital, and so I come down, and she's very reluctant to come in to the hospital because she's worried about her health insurance, and her husband is there, and so is her six—year—old son. So I have this very serious conversation about, "Well, the only way to fix dehydration is with proper intravenous therapy, I think we can buff you up, and get you out of here in twenty-four hours, and it really shouldn't be too expensive a proposition. I know you're concerned with expense and time." So the husband is trying to convince her that this is the way to go. And in the meantime, their six— or seven—year—old son is absolutely cracking up. He's just laughing so hard that nobody can quite believe it. And his mother, with her last ounce of strength, is saying, "Shhh, shhh." And finally the father takes him by the shoulder and says, "What's so funny?" And he points to me and he says, "He looks just like Eliza." Well, Eliza was our youngest daughter and she was in class with him at primary school. (laughter) So when this was explained, the woman immediately consented to be admitted to the hospital, and, good as gold, she was able to go home the next afternoon.

The next emergency department story comes after the snowstorm, 1978 storm. As I told you, I was on call and had to get to the hospital, whether I liked it or not, the morning after in snowshoes and hitching a ride on a snowplow got me there. And there, standing in the doorway of the emergency department, was a patient of mine who I used to nickname Calamity Joe because he had—he would always have an accident of a careless, self—inflicted type just when you least wanted to see him have an accident. (laughs) And he's standing in the door—he's standing in the doorway of the hospital, finger dripping blood, he'd put it in his snow blower to get something out, and he looks at me, as I come in in my boots carrying my snowshoes, and he says, "You know, doc, you always keep me waiting." (laughter)

MK: Always keep me waiting.

CK: I bet you weren't laughing then.

HV: No, no, no, but you know—you know something? It only hurts when I don't laugh. (laughter) But we all got through it, except there was one man who worked nights in the emergency department, and he had the misfortune to be working the night of the snowstorm. And that meant that he was pinned down in the hospital for at least four days. And one day, he had a little time, so he shoveled out a little pouch in the snow where he thought he could put his car and maybe get out and get home. So, no sooner has he finished doing this, than he looks up and the executive director of the hospital is pulling in to the pouch that he has dug himself. (laughs) And he's been on for three nights, and when you're on at night, you don't get proper sleep during the day, and he just lost it. He began kicking the tires and fenders of the executive director's car. And it was my misfortune at that time to be the medical director of the emergency department. So I get a call from the executive director, and he says, "I don't know what to do. Your employee is having a tantrum and is kicking my car to shreds." (laughter) That was one of the more interesting disputations to be resolved.

MK: 00:46:27 So you acquired a background in mediation, whether you went looking for it or not.

HV: Well, I think you do—I think that happens to you in medical practice. Families—families bring forth opportunities to mediate.

MK: Well, this has been—this has been absolutely wonderful. Is there anything else that we should have asked you that we didn't? I don't want you to feel shortchanged here.

HV: No. It's been a—it's been a wonderful ride and the—we couldn't have stumbled on a better place to live and to practice than Concord.

MK: Well, they were—they were lucky to get you I think.

HV: Well, thank you for your—thank you for your kind words and thanks for doing this important work.

MK: You're very welcome. Thank you.

00:47:32 (end of audio)

Back to the Oral History Program Collection page

Back to Finding Aids page

Back to Special Collections page

Home