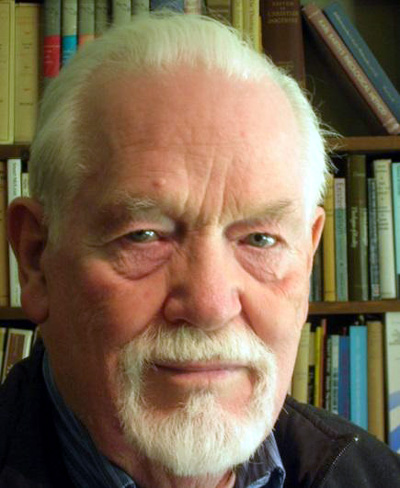

David Stephens

Interviewer: Michael and Carrie Kline

Date: May 8, 2014

Place of Interview: Concord, Massachusetts, Free Public Library

Transcriptionist: Adept Word Management

Click for audio: part 1, part 2.

Audio file is in .mp3 format.

David Stephens: 00:00:00 I'll start over.

David Stephens: 00:00:00 I'll start over.

Michael Kline: Describe this again. I've got it on now. So just describe—just do what you said to us.

DS: Okay. Basically, what I've done here is I've prepared 2 documents. One of them is a kind of a timeline of my own background and what we're down in Concord for, which—you know, such as it is—anybody can do—the same act can be done by 2 people with different points of view. So what I've also written is a paper called "A Transplant's Grundsatz." It's a perspective that I'm bringing to this whole process of being in Concord and being a Concordian. And what I want to do is—I want to give you first of all copies of both of those—but I want to start off, if I may, just simply read—

MK: And these—this—

DS: And these CDs are—contain copies, both a PDF copy and a Word copy of both documents and of the photo, so that you can use this to strip the photo out if you need it or whatever.

MK: Okay.

DS: And I—this one I'll give to—

MK: Oh, that's a duplicate.

DS: Yeah, duplicate, so.

MK: So would you—start out if you would, just say—introduce yourself—my name is—

DS: Sure. My name is David Stephens.

MK: And your date of birth?

DS: And my date of birth is June 21st, 1932. I was born in Las Vegas, Nevada.

MK: Okay.

DS: And I'm 82 years old, coming next month. (laughs) So I'm—married—I have—

MK: 00:01:29 And what is it you're going to read us?

DS: I have three children, and they are all grown. And one is a pilot, a decorated military and professional individual. Another one is a defense attorney in Oregon. And another one is a pastor—former pastor—and a NASA contracting officer. I've been educated in—I've been blessed with a fairly good education. And I can give you that later on. But what I want to do is—before I do any of that—I want to give you kind of the general perspective that I'm bringing to this whole business. So it may make more sense to the reader or whatever.

MK: Okay.

DS: It's titled, "A Transplant's View of Concord, a Personal Perspective." Quote—Concord is an attractive, well-maintained, expensive, historical, New England town run by oligarchs. Everyone looks at the world through his own perspective, but the world is not perspectival. The world challenges our perspectives for conformity to its objective constraints. There are some things in the world that can be changed and much that cannot. We spend our lives learning the difference and adapting to what cannot be changed. One of those stable features of the world is human nature. Human nature is malleable by cultural forces, education, and by hard experience. Both humanists and theists agree that people are valuable, that they must be responsible, and to be responsible they must be free. We conduct ourselves in the light of how we understand ourselves and the presuppositions that define our value judgments, what it means to be responsible, and what it means to be free. It is those defining presuppositions that are challenged by the world in which we have been cast with no choice on our part. We learn soon enough that we are constrained by a world we did not make. It constrains our choices in firm, implacable ways. But we also learn that those constraints are boundaries within which we can choose to make the world more or less to our liking.

Characteristically we chafe at the constraints and sometimes act as if we made the world and all values center upon us. In so doing, we are inclined to assert our primacy and indulge our ambitions at the expense of others and our own peace of mind. A war of all against all ensues. Our grasp of what is real and what is artifact becomes blurred, and we are driven to dominate what seems to be overly constraining upon us. Absent a larger frame of reference, we are inclined to libertarianism or to determinism, and we seek to dominate whatever fails to conform to that inclination. It is a suicidal inclination. It despairs a truth, firm boundaries of responsibility, and of effective will. Government has been instituted among us according to positive, constructed law in the absence of objective moral and civil law. Apart from divine law, positive law is a function of the most powerful and willful among us. And we descend inevitably again and again into the tyranny of the strongest, a kind of Darwinian survival of the fittest and strongest. The value of people is diminished. Constraints of responsibility become chains of slavery. And freedom is constrained by the limited length of our chains.

As a Christian, I affirm the primacy of God and Christ, Who made us in His image. He defined responsibility in terms of love of God and love of man, and our freedom as liberty, responsible freedom, not the license of raw freedom. Our freedom is bounded by love, the essence of responsibility. The image of the loving God in us constitutes our basic humanity. Without the primacy of God in us, our nature demands love that we cannot render and seeks love that we cannot find. And that failure we cannot find ourselves. In these terms, governance does not begin with self-governance, but with the divine governance of love, within which we learn self-governance and the boundaries of personal and civic responsibility with freedom. Christians do not find truth as a product of either radical individualism or radical collectivism. Rather, they see these as opposite, warring sides of the same coin of the primacy of the self. Thus, in a world given to primacy of the self, Christians serve as a balancing element, as salt, in the political contests of secular politics, injecting judgments that affirm what is good and oppose what is evil in terms of the divine law of love. Accordingly they become as grist in the harsh millstones of individual ego and the collective ego, winning less often than they lose in their attempts to make life bearable for their neighbors in spite of the inversion of love and hatred into dominance.

00:06:38 Concord, Massachusetts, is simply a microcosm of this cosmic human dilemma. Oligarchy that tends to tyrannous dominance is a plain feature of Concord's governance. It converts an instrument of the will of the majority—open Town Meeting—into an instrument of ratification of the will of a small minority. A few hundred self-selected legislators dominate the concerns of about 18,000 citizens of whom 76% are qualified registered voters. This oligarchy is pragmatic and tenacious in their grasp of power and the instrument of its legislation. Fairness is trumped by fear of loss of control and the sacrifice by disenfranchisement of over 90% of the qualified voters. Prissy words and proud posture cover an unrelenting disdain for the voters who elect them to office. Pretense of volunteerism is exposed by the repetitious recycling of those of one mind with the oligarchs, many of whom have no realization that they are in fact tyrannical in disposition and act.

This view of Concord by a transplant from Nevada is the fruit of experience of life in Concord, not an immediate epiphany in becoming a resident. I have often said that Concord is a beautiful town but that I wish I didn't know as much about it as I do now. There is some truth that ignorance is bliss except when reality slaps you in the face. Then there's no return to innocence, and one must do what he can for good that is within reach of his hands.

In sharp contrast to what Concord once was and is ceremoniously celebrated, Concord is today a prototypical postmodern community that exhibits this collectivist axiological frame of reference in its governance. The creation of the Concord Forum in 1995 was in direct response to the abuse of this axiological bent and behavior. It has salted Concord in many constructive ways but cannot claim to have won the majority of its challenges. Yet it is known, and sometimes even feared and hated, for the challenge it presents to the pragmatic, narrow governance that reflects so well the primacy of the self. The hard core of the Concord Forum is a few Christians who have many silent supporters. It seeks to serve rather than to be served, and it takes its licks as within the providence of God, whether it wins, loses, or pulls a draw. It is a human organization that has to learn obedience as it tries to be salt. (Finishes reading document) 00:09:28

That's the perspective I come from, that I bring to what you will hear later on in these things. There are many things that we will be talking about perhaps or you'll have questions about—are to be understood within that perspective, and hopefully it will be enlightening. It won't be—some of the things I have to say I don't particularly like to have to say, but I think truth requires it, just as I've said what I've said here. That's not an easy thing to say about Concord. I've spent most of my life here. And I have many good friends here. But the truth is the truth, and there's no point in just pussy-footing around it. (laughs)

MK: All right.

DS: All right, so, what would you like—where would you like to go from here?

MK: 00:10:15 Oh, I'd like you to put the papers away, and let's just talk for a while.

DS: Okay.

MK: And, uh—

Carrie Kline: The mike picks up any sort of rustling, too.

MK: Yeah.

DS: Oh, yeah, okay.

MK: These buttons against—

DS: Oh, these buttons are—

MK: Are glass.

DS: Let me take off my coat, and that will stop it.

MK: Why don't you—you might be more comfortable that way.

DS: Well, I like the coat, but I—I'm comfortable in—very comfortable clothes. Okay, is that better?

MK: Yes, sir. Why don't you, if you want to, talk a little more about your own people and where you were raised.

DS: Sure.

MK: Because that gives us a context for this—

DS: Absolutely. Absolutely.

MK: For this statement of your beliefs and concerns, which I thought was very clearly written.

DS: Well, like I say, I was born in Las Vegas 82 years ago. And I was born there when there were only 5,000 people in town. And my father was one of two postal carriers. He carried the residential district, and somebody else carried the business district. And that's who they were at that time, in 1932. My mother's grandparents—my mother's parents—came to Vegas to work on the dam that was being constructed—it was the Boulder Dam—at the time. And so the town began to grow under those circumstances. But we weren't particularly well-heeled, to say the least, but we—we had a great deal of freedom to come and go. I lived within a block of the deserts that stretched to the mountains. So at the age of 14, I could take my .22, and a friend would get the ammunition, and we'd go out and shoot up the desert with no constraints. There was no problem. And the rifle I used, for instance, was a little rolling block Stevens that my step-grandfather had used in Missouri many years before—before the turn of the century. And on one—

MK: 00:12:27 "Shoot up the desert," did you say?

DS: Yeah, just go out—

MK: I don't hear very well either. I'm sorry.

DS: Oh, okay. Now, you're going out and just—we would target—you know, stumps and squirrels and stuff like that. (laughs) Without—we had no adult supervision. We had a good time. We didn't hurt each other.

But we learned also, from the experience of my step-grandfather, whose rifle this was when he was a boy, the dangers. He and a friend were going through a fence one day on a hunting thing. The gun went off and killed his friend. He kept the gun. And his children and his grandchildren used that gun. Always with that story attached to it. We learned to be careful with it. We weren't—guns were not something to be hated, something to be feared, shunned at all expense, as it is in this politically correct world today. We learned that they were important, they were tools, and they were to be used responsibly. My parents were responsible people. My father was—as I said—was a postal carrier. And during the Depression, he had to sell a very valuable piece of property, worth millions later on, just simply because he had to pay his bills. And I've seen my father cry in disappointment. But I've never seen him lie. Or use foul language. Or do the things which were common. He was a bit of a—out of step with a lot of people in some respects because he was a man of unquestioned integrity. And he started a business one time. He was in the Post Office, and he thought--after the war we had our Depression. Before the war, he was working and so we had a steady income from the Postal Service.

After the War, the Depression hit us. And I remember one time, coming home from school, and they weren't going to have a Christmas tree. And I thought, well, that's not right. So I went out and I spent 50 cents on a Christmas tree, brought it home, and I got bawled out for it. Because we didn't have 50 cents. That 50 cents would have gone a long way. And so, I learned how to do without, but to do without, without crabbing about it. My father worked hard. He hurt himself building a—what was hoped to be—with some Nuttall's—he injured himself and became physically really hurt for many years. And I thought, well—at the same time I was going off to school—I saw him come up from where he was being treated. He looked like a skeleton in a suit. And yet he—and he told me—he says, "Dave, I was—I thought I was going to die. And I could see, as if through a tunnel, the light on the other side. But I decided I didn't want to go. Because I didn't want to leave your mother and you boys to go on your own." So he fought, came back, he recovered his strength, and later retired from the Post Office. But he set an example for my brother and I, which in a sense—in the eulogy, I said, "We are to be his epitaph." Pardon me. (laughs)

MK: It's a beautiful story.

DS: Well, I didn't—telling that one—so I'm a little choked up about it.

MK: It's all right. Take your time.

DS: 00:16:13 He was a good man. A hard man. I got plenty of beatings from him. (laughs) But he was a good man. I learned obedience from him. And one day he says, "Dave, you have a hell of a temper, and you've got to learn to control it." He says, "I have one, too. And I had to learn to transfer that energy into constructive channels instead of losing my temper." And I saw him do things, which would take too long to relate here, which—which were very effective in righting wrongs in his—in the family, in his work situation. He sacrificed himself for that purpose. So, he was a role model. (laughs) So it's for both my brother and I.

MK: And your mother?

DS: And my mother? She was a cripple. She was born whole, but she had spinal meningitis and polio simultaneously when she was five years old. Up to that point, her father had homesteaded Baudette, Minnesota. And she would—and he had—they lived above a bar that he set up. (laughs) And he would take her around, and she'd dance on the piano and everything when they were playing the music. And she would—she was a lively person. But she, too, had her sense of responsibility and—in a different way—she was more vivacious than my father, and of course that led to tensions. But they were—it was a good thing because I learned, in that context, between the two of them, to try to find a middle way—in one dramatic situation that I won't go into detail with—but I found myself going between two rooms, where they were in different rooms crying. And it had an effect on me. It made me challenge the question of the "either/or" categories that people like to foist us into. You either got to do this or you got to do that. I loved them both. And they were both right, and they were both wrong. (laughs) And as a consequence, I—that affected me really over my whole life. And it's been—it was a formative influence.

I was very shy when I was very young. But my grandfather, my mother's dad, was a Norwegian, and he was a bit of a rascal. And he had been a—well, he'd run liquor from Canada into the United States at the Montana border during the Prohibition. But he was a farmer. He had homesteaded Baudette. He was a hard man, too. And people didn't much like him. But he loved us, and on his death bed, he found his faith that had been skewered by his mother who had been a housekeeper for Dwight L. Moody, who was a hellion, and he'd seen her send his father into the backyard crying because of the way in which she had treated him. So he turned against religious things. And only as he came to the end of his life, he realized what was really important. So it was a—it was a deathbed conversion, but it was a real one. And so that was some of the—our families are mixed.

MK: So your father fell in love with a crippled girl?

DS: Yes, yes. They were going to the Methodist Church, and she set her cap for him, and she caught him. (laughs)

MK: She "set her cap"—?

DS: Set her cap—that's an expression.

MK: That's great.

DS: That's a northern expression of a woman who sets her cap to get somebody. It's kind of an odd expression.

MK: 00:20:44 Was your brother older or younger?

DS: Younger—22 months younger. And the difference between us—he was more the outdoor person. I was more the indoor person. But we have—over the years, our temperaments have mellowed, and I've become more aggressive, and he's become a little more withdrawn. (laughs) So, you know, over the years, circumstances tend to either break us or make us. And in our cases—he was—he's very adventurous. He took a six-month solo tour of the Pacific in a thirty-five-foot boat. And it's in the Concord Carlisle TV archives, the whole story. I put it up on—the story up.

MK: So what was your path to Concord? Can you talk about that?

DS: My path to Concord?

MK: Yes.

DS: Very circuitous. I never intended it. (laughs) What I did is I—it starts with going to school. I went to Cal Tech for a while, and while at Cal Tech, I was confronted by an individual who was from—in the varsity—who confronted me with the claims of Christ. And I resisted with might and main until I couldn't resist any further. And I remember the night I was converted, I was driven out to the—a little olive garden beside the great—the place where the 200-inch telescope—Mount Palomar telescope—was ground. And there I experienced His presence in my life, and it's never left. But that was the beginning of things because at Cal Tech, I became active in—in the varsity and other things. And gradually I came to the conviction that I should go to seminary. So I left Cal Tech and went to the Pasadena Nazarene College, which was just up the road a ways from Cal Tech, and there I had the occasion to meet some—I've met—in my tour, I've met fine people—perhaps the best in their field—as I've gone along. I went to Nazarene College, and I met the systematic theologian for the Nazarenes there and some of his people. I went to Fuller Seminary, and I met the—people like Carnell and Carl F. H. Henry and all of those early yield evangelicals, freshly minted. (laughs) I saw that, and I was there at the peak, when all of these different peeking out.

When I was at Cal Tech, I was there with Linus Pauling. I studied under him and other people. People whose names—it sounds like name dropping—but I just happened to be there at those times. And I—and each one of them contributed to me. Millikan—of the famous oil drops—Millikan's oil drop experiment—invited me home for Thanksgiving one time, thinking I—and I had to turn him down. I had to go home. (laughs) So, you know, I was bumping into people who were responsible people. Millikan was always talking about, "Boys, remember your Creator." (laughs) And he was always kind of mocked for that. But I went from the Nazarene College, and then I went to Fuller Seminary where I got my M.Div. I got a bachelor's degree in philosophy at the Nazarene College. I got my Master of Divinity in theology in Fuller Seminary. Then I went on to get—to pursue a degree in philosophy at Boston University. And by that time, I had married, in 1954, and Randall had been born, my

eldest. And he spoke, said "mama" the first time at Niagara Falls. (laughs) And so, I joined the program, and then the family began to grow and I was—at the same time I was—

MK: 00:24:53 Joined the program?

DS: Joined the program at Boston University, yeah. And the family began to grow, and I was working at MIT Instrumentation Lab. So I really, in my life, I had ran two tracks. A technical one, to keep myself in threads and the family in goods, and the academic one, which, when I had a choice—if I had a choice of advancement or going to school, I went to school. So I was always sort of available—I was cheap meat for the seat when they wanted to hire somebody because I hadn't taken the big buck route. So at Boston University, while I was there, my other two sons, Dan and Scott were born. And it put a crimp in my style. I could not continue with that doctoral program. But they came back to me and said, "Well, finish getting a master's degree." So I did. I got the master's degree in 1975 in philosophy. And further dissertation on epistemology. Then my wind was up, and so I said, well, maybe I have the opportunity to go on.

So I found out that there was a joint graduate program at Boston College and Andover Newton Theological School in theology. So I checked that out, and they granted me a full scholarship for the program for two years of training and leading to a doctorate, which I did. And through the set of circumstances there, it was—I joined that program the day my eldest son joined the Army. (laughs) And I was in need of $2,000 that I thought I was going to get from them and didn't get it. And—but then it laid on my heart to get a job as a guard. And in that year—two years—I earned exactly $2,000. And at the end of the first year, I said, "Lord, I need to get a job." (laughs) "But I can't take the time to get it." Well, meantime, my Karmann Ghia motor had failed, and I had to pay $500 for that, so I was really up against the wall. And all of a sudden—I had no more prayed that—within the week, a friend called and said, "Dave, what are you doing?" I told him. "Want to work for me full time?" No. I got used to this. He said, "Well, tell you what, come work for me, and you can pick your own hours and you can be an R&D engineer for me at Hollis."

MK: R and—?

DS: Research and development engineer.

CK: At where?

DS: At Hollis Engineering. And so I said, "Okay." So when I finished the course with that first year, I had earned the $2,000 I needed, I had a job, and the school owed me exactly $500. (laughs) The good Lord put the board under my feet. So anyway, then I had to take a break because I had to now continue to support my family, and so I worked for a number of companies. Over the years, I worked for about 10 companies—over the four years that I was involved in this—and I've been laid off about 7 times. And each time, my wife said, "I think you enjoy being laid off more than you did working." (laughs) Which in some sense was true.

But in 1972 or thereabouts, I got signed up for this joint project program. And then things took a—I had to focus on making a living. So for the next several years, I did that. And so I didn't finish my—I finished the master's degree, but the doctoral degree was set aside and—but I kept signing up every year. And finally says, "You know, Dave, you really ought to finish this thing." So I did. And in 1999 I got my doctorate in systematic theology from Boston College. And that led to some other things. I've taught some patristic courses in the period of—at Boston College as a guest lecturer. And that's been an ongoing thing for the past eight years or so. But, how did I get here? Well, when I was—when I was working at Hollis—no, at—I'm sorry—at Itech Corporation—

MK: 00:29:36 At?

DS: At Itech Corporation.

MK: Itech.

DS: Yeah, I worked there from about 1967 to ‘71. We determined it was necessary to make a move. So we looked around for a place and finally found this place under construction in Concord. And it worked out very well for us. We were able to swing it. And so we came to Concord as a consequence of moving from Watertown, where I'd been living at the time—we'd been living at the time—in, uh—well, actually, September of 1969. And that—we've been here ever since. I've lived longer in Concord than I've lived anywhere else in my life, longer than Vegas or any other place. And so Concord really has become a home. But you know, there's an old saying in New England, "You aren't really a member of the community until you die." (laughs) That's not so much true now, but it used to be. You were never really accepted as a full member of the community if you weren't native, until such time as you had served your term and went under the sod. But, now Concord has changed. Its—its shape, its demographics, its cultural features, significantly in the last 200 years. And I kind of fell into the—this business of governance—kind of by a fluke. When we first moved in, hunters were—came along—and one hunter swung his 12-gauge [shotgun] past me while--I was on the back porch--firing at a bird, in which case I went around and I got the new neighbors signed up in what we called the Oakview Association.

CK: The what?

DS: The Oakview Association, which—and we went the next spring to the Town Meeting and had them change the by-law, the hunting by-law. They increased the fine and they made it much stiffer.

MK: The fine for—?

DS: The fine for violating the by-law—the hunters coming within 200 feet of the house and they weren't allowed to hunt in—on the conservation land. Our property was within 100 feet—200 feet of the property line. And a year or two later, when my two youngest sons were out playing in the corner of the lot, and my eldest son and I had surveyed the 200 line. So we knew where it was, and we put markers out that said, "You are within 200 feet and there's no shooting." Well, two hunters came within about 25 yards of my youngest sons, fired over their head, and my dog, Trina, a Norwegian elkhound began to pursue them. I called the police and said, "I'm strapping on a .357 magnum handgun, and I'm going to get him. I'm going out there to meet him. You be there before I do." And I did. I put on that handgun, and I went out. And the police had gotten there first. And he'd interviewed him—these guys—and he said, "Well, it's your word against theirs." I says, "Okay." So I turned to them and I was not kind in my words. But I read them thoroughly. And in the course of reading them out, they admitted that they knew where they were, in front of the officer. Then they knew that they had confessed to this. Rather than press the charges, I said—pardon my language—"You sons of bitches better get out of here and stay out of here. If you ever come back—you take your guns, you get out of here—because I'm not going to be responsible if I ever see you in this area again with a gun in your hand." They left. The officer didn't say anything to me. They took off. And as far as I know, they never came back.

But then we went ahead and we pursued it further because the town was not enforcing the laws. And so we made a case, and finally—actually in Town Meeting—it was the second Town Meeting—that I'd ever been to. (laughs) And they saw where we were coming from, and they understood that they had to do something more than just talk about it. That was my introduction to Town Meeting and my introduction to the town. There was hostility of the town to the new development—

MK: 00:34:11 Hostility in the town to the new development?

DS: Yes, because—you know, there was still—this was 1969 and there were a lot of people around here, "you have no business here," even though they had authorized the building of the development. And then we had struggles with the developer itself who had done some slipshod work. And so the Oakview Association became a bit of an active entity on several fronts, as a consequence of—

MK: How many residences did this—?

DS: Well, let's see. It's hard to say.

MK: Roughly.

DS: Roughly, I'd say about 50 in that area. And we were right on the edge of the conservation property off of Virginia Road and Old Bedford Road. And so we—that got us involved in a lot of the town efforts. And when we were struggling with the builder and struggling with the town to try to get some kind of fair treatment, we had to do some strange things sometimes. At one point, I took the town manager by his collar and dragged him up in front of one of the selectmen, and I said, "You said that you were going to do this and you haven't." He wasn't fixing a broken drain that was causing water to back up in the development. And I said, "I want this done. I want it done now." And of course—and within a week it was done. But you know reality slaps you in the face. You don't go in—I didn't go in expecting this kind of thing.

But also, I joined the Concord Minutemen when I got in place. The Concord Minutemen is an organization that's a reorganization of the original Concord men, but there are some ceremonial functions, and I'd become part of that in the early days. And through that, I also got to meet some of the selectmen. And also we are within 5,000 feet—within a mile—3/4 of a mile—of the airport.

So we're kind of in the quadrangle. And airplanes taking in and out—going in and out—landing in and out—doing takeoffs and landings exercises as training—they were flying down within a couple hundred feet over the—over the development. At one point, some guy with full flaps was doing S-turns going down the street. I turned him in. And then I built some instruments, went out there and plotted several hundred flight patterns, we were able to determine their elevation and location, and I was turning these guys in. And it was making me a persona non grata, so they had a call—they had a meeting eventually to try to deal with this. In the meantime, I had been appointed to the Concord Airport Committee. And that was overseeing some complaints—or concerns—that Concord had about the way that the airport was dealing with the town. So I had become part of that. And then when I did this, the FAA, the Massport officials, and the flyers—or those two—anyway the airport officials and the FAA—set up a meeting. They were going to meet my needs. (laughs) And so they went there and I happened to have better hearing than I have now. And I overheard the tower official say, "Isn't that the Concord noise abatement procedure?"

MK: 00:37:37 Isn't that—?

DS: Concord noise abatement procedure. I heard him say that—the tower official say that—they didn't think I heard it. So when they got done patronizing me, I said, "Don't patronize me. This isn't—you're not doing this for me. You're doing this according to the Concord noise abate procedure, and besides you've got these flyers who busted into this meeting who are ticked off at you because you were telling me that you made the situation tougher for them just to satisfy me. That's not true." I says, "I don't agree with that." I said, "I'm not any more interested in causing them problems than having them cause me problems." At which point they turned on my side. Instead of threatening to sue me, now they were on my side.

MK: So your argument was to try to bring it into compliance, right?

DS: Right. Exactly. And they were violating the fundamental rules of elevation and so forth. So they had a fly in. And one of the guys that was a competitor—flying chipmunk in competition—he was head of the flying club at one point. And he was doing the pilot pitch. We had FAA people and Massport people on the back—my backyard—on those instruments along with my son, and we would swap. We'd fly and vice versa. And then the airport would take readings to see how good our readings were. They confirmed our readings. And the pilots were on my side full up to here. And the Massport officials had egg on their face. So then they appointed me to the Hanscom Advisory Committee, which was a transfer of Hanscom property from the military to the state. And I was involved in that, and I had made the motion that they should get the concerns of the town of Concord and the surrounding towns so that they could make a master plan.

Well, they agreed with it, and then they turned to me and said, "And you're going to be chairman of the committee that does that, and you're not going to get these people together because they haven't been together since the Civil War." I says, "Well, don't count your chickens." I sat down—and this is where I scared myself—and I learned something about politics in that process. I sat at my kitchen table, I wrote without consultation with anybody, the concerns of the town of Concord about the flight situation. I took it to the Chairman of the Board of Elders, he didn't hold a meeting, he looked at it, and he says, "Go with it." Now, I'm sitting there—I'm writing this stuff by myself. I take it to my committee, and I said, "Take this, and I suggest you take this to your Boards of Selectmen, have them modify it any way they want, and that way you can have your own set of concerns for each town." Well, of course, what the selectmen did in those towns, they just modified it slightly here and there.

So in effect, I wrote all of the concerns of the towns about Hanscom Field through that one exercise. And it scared me because I realized that I was not an elected official. I was one individual who had extraordinary power within his hand. I could screw the town up and everybody else up by being irresponsible, and I realized there are people doing this all the time. So I learned something about the dangers of that, but it worked. The FAA uses—at least the last I heard—still uses that master plan approach to deal with other problems with communities, and the Massport did create a master plan based on these concerns, and those concerns lasted for something like 15 years afterwards. Things have changed since then and a lot of other problems come up, so I'm no longer on that—in that circle. But that was another entrée into the political life of Concord. At that time—and I say this with no offense to the distaff—all my—I have more friends that are women than men, but all the men—with the exception of one woman—all the selectmen were men. And they had a—they were—they'd bring a different outlook on political matters than women do. And I'm not saying which is best or not, but it's a difference.

MK: 00:42:20 What is the difference?

DS: The difference between men and women.

MK: Okay.

DS: (laughs) Women tend to be more intuitive. They tend to be a little bit more sensitive to slight. They tend to be a little less aggressive—except when they're being pushed, and then they become like mother bears. Men tend to have a more even keel. They're more deliberate. They're used to taking blows. Yeah, they roll with them. And they will tend sometimes to overlook those slights—the better ones. We're all humans so this isn't an absolute categorization. It's not fair to make that generalization. But—

MK: But the tender complexion of the select board of selectmen was troubling to you.

DS: Well, it has—

MK: Or at least telling.

DS: It has become telling. Right now in the Concord, there are only two men out of the—on the board—and there are three women. And that's not—and I'm not casting any reflections on them. I'm simply saying the difference in the way they approach problems is significant. And sometimes a strong man in the chairmanship can drive the situation when he shouldn't. So I've seen that. I'm not—so all I'm saying is the complexion, the demographic complexion, of the boards and so forth—now there's something—there are only fifteen elected officials in Concord. And there are 18,000 people in town—17,000 people in town. There are over 200 at last count—over 250 appointed officials that are appointed by these fifteen officials. So when I say Concord's run by an oligarchy, I'm serious. I'm not just throwing words around. This oligarchy goes back to—prior to the Revolutionary War. It's a very interesting history.

Prior to the Revolutionary War, they had committees of safety and communication to get around the royal edicts and constraints that they were coming under. And so, the rebels decided, well, they'll just—we'll just do it ourselves. We'll have our own congresses and everything else, and the devil take the hindmost. When the war broke out, these committees became, as in the case of Concord, generally the ruling bodies in the town. They selected the men to go to the war, and they brought sanctions against the Tories and all the rest of it. They ran the town. After the war was over, most towns just abandoned them. Concord didn't. Concord formed what was called the Social Circle, which was composed of the same people who were on these boards of safety and communication. And they continued to run the town after the war. And the—that Social Circle exists today. What they do is they have a—you don't always know who they are, the membership is closed circuit, you don't know necessarily—some people know. And you can guess who some of them are. But they aren't necessarily elected officials; they're people who they think have good judgment or whatever, according to their likes, and capable of running the town better. And it could be a businessman, it could be a shopkeeper, it could be a tanner, whatever. But when those people would die, they would write up their biography, elect another man to take his place, and put that biography in the Middlesex Bank vault, and it's there.

I met a man one time who was fired who happened to—who had a chance to see that file. And it's secret. He was not supposed to see that file, and they fired him—at the Middlesex—that's within the last fifteen years. It's used to be composed of all men. Now it's a mix of men and women, [commonly people]—former officials and stuff—have become part of it. Not all are elected to it. And it still remains a bit of a mystery who they are. But they're also facing a problem; that becomes obvious. Governance of Concord has become much more complicated because of the changing demographics. At the time of the colonial days, Town Meeting was a required attendance thing. You attended or you got fined. There was no backing out. And if you didn't attend and you wanted to pay the fines, you were suspect because you were—you were fighting against the—you know, you were a threat to the establishment. Well, as the passage of time went on, after the war and with the expansion westward and all the things that go with that, the people—transportation of people back and forth to town became more and more mixed. There was always completely the original old families. There were other people coming in from out of town. And—

MK: 00:47:33 Would it be kosher to ask for some of the principal names—or some of the family names of those principal—who it—

DS: The original ones?

MK: Who transitioned into—

DS: Well, I—I don't know that I could give you all of those names. I know some of the names that—like Wheeler and some of these people that are old line, go way back. But people like myself who came in later years and others in the period from—after the Civil War with the expansion westward and all that—the demography of Concord has changed. And there's no longer a shared cultural set of values as there was in the parochialism of old Concord, where people pretty much held the same set of values, and they could do business in other—they could do their governance out of their hip pockets, and nobody would worry about it because they'd know—they trusted Joe and Pete and Henry—but nowadays, that's not the case. Most people don't know these people. And 17,000 people being run by fifteen means you have a span of control that's pretty extensive. And those fifteen appoint something like 250 or more individuals to the different boards and—

MK: These are volunteers?

DS: 00:48:55 Ostensibly they're volunteers. They have what's called a green card system. The green card system—you'll always hear the moderates say, "See this green card? Go out and fill one of these up because—if you want to serve, fill out the green card, and you'll be selected." Well, they aren't. I had occasion to see and to examine in detail the green card file. It's no longer available. But I made copies of it, and what you saw was a recycling of those who had the same point of view of the oligarchs, the people who—I appoint you to, say, the—some committee—and you do very well. Well, now I've got her, she wants to be part of it, but I know you. I'm unsure about her leanings, so what do I do? I appoint you. And it's not something that's intentional always, but it is a fact, that people are recycled. And I've seen people who put their names on those cards that have been there for years, very qualified people, who never so much as got a yes or no. And what you have—what you have is this—between the impulse of the oligarchic structure of the Social Circle, which is also a religious connection with the Unitarian Church and with the Congregational Church, they were—that's a very interesting relationship between the churches.

When the Congregational Church burned down, the Unitarians helped them build it up again, and when the—but they had separated from the Unitarian church because they had a theological difference, and there was great pain in the town because friends were divided over this. And when the Unitarian Church burned down, the Congregational helped them build their church. So there was this sense of community. I don't think you'd find that today in Concord quite like that. And, matter of fact, the nature—the axiological nature—of the town has changed drastically in terms of the modern—postmodern—issues. But that doesn't mean that they didn't have their fights earlier. There was a time when the Masons came under severe attack, and old friends were divided forever because the Masons were accused of murderous inclinations and actions. And it became a cause célèbre in the 1800s. And it divided the town in that connection very seriously.

So what I'm talking about is really a town that's very complex in both its history and in its axiology, its value structure. And its governance reflects that. Its governance reflects an oligarchic posture. And to say that to them would be to insult them. Because most of them don't realize that. Most of them don't realize that they are in fact an oligarchy. They're the few who are dominating the many out of pragmatism. It's a pragmatic thing to appoint you two or three times to different committees as opposed to your friend. Okay? We know them and—it works, you know? So why not? Why shake the boat? Matter of fact, we just recently had a Town Meeting where we were trying to—and I was one of the principals involved—where we were trying to get them to have voting at the polls instead of a Town Meeting. See, Town Meeting requires a—open Town Meeting now requires that voters be physically present at the deliberations and at the sessions to vote. Well, now you've got—you've got 12,790 voters in town. There isn't any venue in town where you can put them together if they wanted to be there. There's just no place for them. You can't do that in a Town Meeting.

Now, other communities—there's something like 500 of them in New England, approaching that number—who have adopted what's called the—sometimes called the Australian ballot where the—those who want to attend the deliberative sessions can, and when the motions have been amended and all the things ready for the final vote, then they get put on a ballot and sent to the polls, as part of Town Meeting, and when Town Meeting's over, that's the end of it. But the voting is done at once instead of every motion coming up and you spending three or four days in a row to vote on half a dozen things, some of which you are probably not interested in. You can deal with them all at one fell swoop. You can be informed by television and other things.

CK: So write it all up.

DS: Pardon?

CK: 00:53:59 Write each one up at some length and then at the polls?

DS: Yeah. Well, what happens is the three of us are having Town Meeting, and we have different issues. We make our decisions on what we think should be. We made the motion, so we think they're available, and then we just present it to the voters at large, and they would judge it. Well, that's not—that's not how it's done in Town Meeting. It's just the three of us can vote on it, and we can tell the people out there what we voted and they have to live with it because they pride themselves as being legislators. But they are self-selected legislators. They are people who elect to be there. And they also can stack Town Meetings. People—you have a special interest like we had a recent water bottle—the bottled water type of thing? The environmentalists in town wanted to prohibit the use of individual bottled water. And the sale of it is now prohibited in town. Now, they got it by stacking Town Meeting.

You get all your friends together, charge in, and unless you really—unless the opposition is equally vociferous and determined, the stacking of Town Meeting is a very effective tool for getting your way in town. In 1994, the second time in history, the Town Meeting was ever so packed that they couldn't conduct business because there was no room for everybody. Because by law they have to—anybody who appears has to be accommodated. In 1994 there was a big flap about transferring funds—of property—from the schools to affordable housing. And it was such a contentious issue that when they had the meeting, people—cars were stacked up on the highways trying to get in, and people were—there just was not enough room to do it. So they decided they'd have to change the venue.

Well, the nearest opportunity was on a Saturday, but that was going to work against the Jewish population, so they decided they'd push it off ‘til two days before Thanksgiving when everybody was leaving town. So, it turned out that they had the meeting, and they found a place, and they were able to shoehorn these people in to this place. And the affordable housing people stood up and invoked the deity against those people who were opposing this. And I could name names—I'm not going to because it would serve no purpose. But the moderator at the time wouldn't allow any answers to questions. It ran this thing through like a ramrod. But this is the second time that it happened. The first time it ever happened was in colonial times. But this instance in 1994 provoked a reaction, and I was part of that reaction. I wrote a paper called "Town Meeting Revisited," which looked at this whole business. I also did a personal survey of all the towns in New Hampshire—of Vermont—to see how their experience with the Australian ballot worked. And what it said—what was—the results were very interesting from the study standpoint. In regular Town Meeting, where you have to be there to vote, as the population exceeds 6,000 people, the turnout is less than five percent at the Town Meeting.

The Australian ballot, when they went to that—people would experience—regardless of the size of the community—you would get anywhere from 20 to 40% of the population regularly turning out at the polls, which was comparable to what you get if you went to federal or state elections. Well, we—somebody proposed an article and got shot down by the selectmen in 1995, and so in 1996 I had put in another motion. And we went for a non-binding ballot question, which means that you put the question up and it's not binding anybody to go it, but it gives you the sentiment of what the town is. Well, they had put up a committee to fight this thing called a Town Meeting Study Committee. I will mention names here: Judy Walpole was the Chairman at the time. And they held a rump meeting—an illegal meeting—in the town manager's office of the selectmen to select the people who were going to be on that committee, with the idea of having only people who were opposed to it. A friend of mine was a member of the selectmen at the time, and he gave up. He told me, he said, "I gave up what I wanted to do so that I could get at least two people on the committee who were favorable to the motion." And the Chairman of the Board of Selectmen went ballistic. She just practically lost it and really went after it.

00:59:13 Well, they had this long study committee and with all of the problems, and I attended those things and challenged them often—you know, I was getting to be kind of a nuisance. And they had—they put four additional—they put six items on the ballot—the original status quo, ours, and then four others to try to get a sense of the town. Well, the town, when we went to the polls, there were 6,000 voters—about 6,030 voters. They rejected those other four and split down the middle within any—the difference was statistically insignificant—it was a 50/50 split in the town. Half of them wanted to go to the ballot, and half of them didn't. The Chairman of the Town Meeting Study Committee was a—was not favoring this. He was a lawyer, and I had crossed swords with him on a number of things he was doing and forced him to open the meeting to television and a few other things. But when that vote was over, he went to—he said to the committee, he said, "Look. The town's divided. You should, I think, go to the state, get legislative approval for the town to do this if they want to, at some time in the future, not to do it now, but," he said, "that's what you should do out of fairness."

Well, he and the two favoring the thing were voted down four to three by the Town Meeting Study Committee. That was eighteen years ago, and they had come up with some innocuous, really, proposals to—to make Town Meeting more friendly and more useful and open, but they—essentially they wanted to—it came that time to go to the Town Meeting and to vote on it, the article ahead in Town Meeting on it. And all my friends were saying, "Don't, don't pass it, don't move it." I said, "Why?" Then of course it dawned on me the very last day at the very last moment. We'd already had a vote at the town, and we know what the town's situation is, and I'm not—so I stood up in Town Meeting, with the permission of the moderator, and explained that we'd already had a vote at the polls. Why should I—why should we now submit it to you for consideration when you've stacked the meeting? They'd gone out and scared all the old folks in town and brought them in on buses, and they had the town all ready to go to kill this thing in the cradle. So I refused to move it. And so it's held on the bench for these past eighteen years. Well, this year, we revived it. I made some TV presentations on the nature of Town Meeting's background, why it—the issue is enfranchisement. And 90% of the voters in town are disenfranchised on the issues the Town Meeting votes on. Well—

MK: 01:02:18 Because of space, because of mobility—of individual mobility—all these other issues.

DS: Absolutely. Distractions. Young people who have children, people who are traveling for business, there's no such thing as an absentee ballot. There's nothing that gives them anything like relief. And you just have to take what Town Meeting says you're going to take. So we're now living in Concord under a ban on bottled water, on individual bottled water, because of this kind of thing. Well, anyway, we decided to go beyond that. They weren't going to have another—they wouldn't let us have another non-binding ballot, and then we decided we didn't want one anyway. What we did is we put a motion for Town Meeting to take this to the legislature, to do what Chairman Lewis had said 18 years later—earlier. And the—it hit the fan. We didn't make a lot of noise about it, and the town had set up the Governance Committee, which is still in—is still seated—with the idea to review the governance of the town. And I've attended all those meetings with the exception of maybe one or two. And yet that committee never looked at Town Meeting, examine the issue, and yet they had the temerity at Town Meeting—just issued here on the 4th—to put out a bulletin saying, "We're opposed to it," and with all kind of specious and captious reasons. So, again, you saw the heavy hand of the oligarchy. And when we got in to Town Meeting, of course it had been stacked again by somebody who was trying to get funds for—backdoor funding—of something that should have been handled another way. I'll explain that in a minute. But they had stacked the meeting with proponents of this measure. And of course it went down in flames—well, handily defeated—our motion was.

01:04:23 Now, I'm not—as I stated earlier—win, lose, or draw—I'm not here complaining, "Oh, they beat us out." There's a process, and we worked with the process. But we're not done. There's a ways to go. We still have alternatives. We'll keep fighting. Just like Nathanael Greene of Revolutionary War fame, the general, when Cornwallis was chasing them in the famous "Race for the Dan River" that was—bordered Virginia and North Carolina—Nathanael Greene had a famous saying: "We fight. We get beat. We get up. And we fight again." And he wore Cornwallis out on that race to the Dan, and finally in Guilford Courthouse in North Carolina, Cornwallis just waxed—and he killed his own people—his own people in danger of being overrun by the colonial soldiers—and so he fired cannons into the backs of them to break the whole thing. And so, again, Greene was beaten, but Cornwallis was exhausted and his men—you have to have resources and you didn't get the help from the Tories in the area—so he went to a famous place called Yorktown. And the rest is history.

We take that as a bit of an encouragement. If you are determined that you want to do something—and the other side does the same thing—they will push a thing over and over and over and over and over again until they get their way. Now, that doesn't mean we're going to get our way. Because look at the odds. We're fighting a cultural and an oligarchical situation that is entrenched, having a two hundred-year history. And I may never live to see the day when that happens. But either it happens, or open Town Meeting, which is an oxymoron today, will go the way of the dodo bird, and something else will be put in its place. It's going to happen. People will not be—will become restive. They're not being allowed to vote on taxes of 70 million dollars that's imposed on them by a school and a town without their input of approval.

People just won't do that for long. They don't want to be treated like serfs. And I'm sort of preaching to the choir here a little bit and getting on my stump, but that's—I really believe that's going to happen. Not in my day maybe, but it's going to happen, and the oligarchy will go down. Now, in the course of things, I've kind of given you a rundown on Town Meeting because that's—they pride themselves as Town Meeting being a legislative body for Concord. And you hear them talking about, oh, open Town Meeting is great, we're all for open Town Meeting. But it's not open because it isn't. People can't be there physically who want to. Twenty percent of the people can't conceivably be there. So, in the meantime—that was the major scraps we've had—but that wasn't the only one. I got involved, as I said, through the airport committee things. I was appointed to a landfill committee where I made a plan from the beginning that there was going to be a minority report. I didn't write it. Somebody else did. (laughs) And I didn't necessarily agree with it.

I became notorious, even hated, by people in town who saw me as the devil from the deep blue sea. I had a—I have a friend whose—who goes unnamed—who told me, he says, "You remember when I got together with you and we worked out to have that debate?"—because the Concord Forum had come into being—and I'll explain that, that's very important—but they came into being as a result of some abuses that we were seeing in the town—he said, "I came to you and we arranged for you to have this debate"—I was moderating it—he said, "I never told my friends because they thought you were the devil, and so I didn't dare tell them, but it worked out great," he says. And we're friends. We disagree on practically all of our political issues. (laughs) But—but there is a difference between people who—and he and I agree. We have different ways of approaching this problem. We want to do the best for our neighbors, but this Town Meeting this year was the first time in the history of Concord where the Town Meeting said we don't want our neighbors in attendance. They don't want—we don't want to extend Town Meeting enfranchisement to our neighbors. They voted it down, and that was the substance of what their decision.

CK: 01:09:39 What neighbors—

DS: Because they said no. We're not going to do this way, and it's the only option that's available. The only other option is—in Town Meeting—is a representative form of Town Meeting, and nobody wants that. Because that's just simply—it legalizes the kind of oligarchy that you're going to have. And nobody wants that. And so they knew, and it was made plain to them, they weren't doing this for our neighbors. You and—I can come to Town Meeting, but you and you cannot because of your circumstances. But there's no need for you to be disenfranchised, and he says, "Forget it." I've heard—and I have heard—members at Town Meeting say, "I don't want my vote watered down." It is a—I'm stressing that very hard, and anybody reading this is going to be offended. I don't—at this particular point, I don't care, because it's the truth. People have taken an attitude toward their neighbors which is hostile to everything I believe and everything that I think is decent and honorable about human interaction. I said in my—what I read at the beginning that love is supposed to be this essence of responsibility, not self-aggrandizement. And what we see here is—today, within the last week—a crime and a first expression of self-aggrandizement on a grand scale. Something like (sighs)—12,000 people, or maybe 11,000 people, cannot—have been denied the ability to come to Town Meeting and vote their will.

MK: Eleven thousand out of—?

DS: —12,790. You take 10%—take 1,200 out of that—maybe you got 10,000, 11,000 people, qualified voters, who cannot—

MK: Because of circumstances.

DS: Yeah, because of circumstances. Now, I'm not saying—there's a difference between saying—we go to the polls—and I've not gone to the polls, not very often, but I have on one or two occasions—but I choose not to go because I can go, I can get my ballot, and I can vote. That's different. And the moderator of the town said, "Well, you know, we disenfranchise people all the time because we don't print all the necessary ballots that meet all the voters." I says, "Yeah, but if they should come out, if more should come out than you printed, you're in trouble, aren't you?" But you see, that's not true in Town Meeting. Town Meeting, you can't be—you can't vote unless you're physically present. You can't vote unless you're physically present. This means of course that the option isn't given to you. You have to be there under these terms and conditions, or you can't vote. And the interesting thing about Town Meeting is that it's rooted—it started among the tribes in Europe. They didn't want to kill each other, so they had—they were the originators of Open Town Meeting.

01:13:02 But the idea of Open Town Meeting was, when I put a sanction on you if you don't come, I'm forcing you to be enfranchised. (laughs) I'm enfranchising you at the risk of your failure of your civic duty. Town Meeting today is just the opposite—it was—then it was—total enfranchisement was the objective—today it is the enfranchisement of the few. Open Town Meeting is an oxymoron in Concord. So, uh, but anyway, coming back to—there are other aspects of this—as I began to get involved in these towns, I started going to all of the—as many of the committee hearings, like the affordable housing and the selectmen meeting—

CK: Can we just stay with Town Meeting for a minute?

DS: Yes. Yes.

CK: So, now, you can also watch it at home on television.

DS: Yes, you can watch it at home.

CK: Conceivably even on a computer, or certainly the technology could be there, to press—to click your mouse or hit your remote and vote that way. I've heard people talk about that. Can you address that a little bit?

DS: Sure. Well, one of their objections that they voice as well: if you do this, now people are going to have a time to second guess what was done in Town Meeting. Really? Just because 100 or 200 people or 300 people decide this is the motion we want to go, and we think it's the right way to go, does that mean that everybody else has to vote that way? No, what people can do is they can say, "I see what they're saying, but I listened to their deliberations, and I thought they didn't get a fair hearing, and I wouldn't have gone that way at all, and I'm going to vote against this." They don't want that. They don't want that response.

CK: Do you, though? I mean, what do you think about voting from home, watching, and then—?

DS: If you can—yeah, if that could be technologically secure and effective, that's fine. But watching it—you can watch the deliberations right now on television. And to say that you have to go to Town Meeting to be informed, to listen to somebody else who's got an agenda, that's the only way you're going to get informed? That's nonsense. And what—what do people do when they go vote for a president? How many people sat down and vetted Obama and his background? Pffft. Not even—not even the polls did. So what you have is—it's foolishness. It's a specious, it's a captious argument, which has no validity in terms of responsibility.

My—for me, responsibility means that if I see you hurting, I'd do my best to help you if I can within the reach of my hand. If I see you being deprived of something that's your right, I want to make sure you get it if I can. It's—it's not a matter of—well, tough for you—I'm at advantage—you know? It's not that kind of thing that responsibility is. That's irresponsible. We call it irresponsible. We know in our hearts it's irresponsible because we're made in the image of God. But people leave the image of God at home when they get power hungry, and when they're used to calling the shots in the community and—so this is—I don't want to dwell too much on that because I don't—I don't want to give a—my perspective of Concord is broader than just Town Meeting. It is a beautiful town. It's well maintained, just as I said. And the people by and large don't even realize they're being oligarchic, they're being despotic. They're happy with what they've got—"We want to keep it this way." (laughs) They want to keep a beautiful town. They don't want to run the risk of somebody saying no to them, though. That there may be another way to do things. That's too much risk, too much risk, we don't want to—we don't want to do that. And I remember—I was in an affordable housing meeting when I was first getting into this hellish business. It had nothing to do with Town Meeting. But affordable housing—

MK: Let's shift that on.

01:17:21 (end of audio A)

00:00:00 (begin audio B)

MK: Can we—can we think toward a 15-minute conclusion now?

DS: Oh, has it been that long? Okay. Well, okay, sure. I didn't mean to take so much time.

MK: Not at all, no. I just—

DS: But let me put it this way: I was attending an affordable housing meeting where there was an adjunct individual who was very prominent in town, whose family goes back a ways, and I was the only one in the audience, and he didn't know me. So he had the—he was bold enough to say, "Well, there was a time when someone was in town wanted to buy the town, and make all the residents tenants, but we couldn't do that because we couldn't get the money for it." He was dead serious. He wasn't joking. So what has been developed in the consequence of that is what's called a Concord Land Conservation Trust. They own about forty percent of the town. What happens to the town—and it's open space largely—the town buys this property, hands it over to the Concord Land Conservation Trust, they manage it and make money off the management. And when you go to walk on that property, they can be very vicious.

It—they—I had a woman come to me one time who had just moved to Concord. She had bought a piece of property in an area that had some white broad board—you know, fences—and they needed paint. And so, it was on her property. So she and her husband painted these nice white fences, made it look nice. And she was out there when along came this individual and another individual and turned her into tears. "Don't you know that this is conservation land and you have to have our permission to even paint it?" It's this attitude. And the attitude was—the same people back—what's called the Concord Land Preservation Act—the state said, "Look, we'll give you one hundred percent matching funds if you opt for a surcharge on the taxes of so much." Well, it turns out the town opted for one-and-a-half percent and the state is only giving them about fifty-six percent of matching funds, but they've used that now. They got something like seven or eight million dollars that they've spent on all kinds of things. But they are the ones that decide how to spend it, and how it's going to be spent, who gets it. And they come to Town Meeting, and they have to have Town Meeting's approval for the disbursement of these funds.

00:02:50 Well, it turns out that the town—and I'm going very, very quickly here, so—the town is now in the process of building a hundred -million dollar high school that doesn't meet the requirements that they presented to the town originally that voted it. There had been a great scandal about it in the town for the last two or three years. The school committee has—believes that they're above accountability, as in most places, and they decided that—on a number of options, which I won't go into all the details—but one of the things that—they were getting money from the state through what's—they call the MSBA. That's a state agency that funds these programs. And part of the regulation is that you have to have all of the options that you want on the table and costed when we decide to pay. And you are prohibited from going back to the town and getting any funding from the town from public funds for those issues that are not on the table afterwards.

Well, they ran a cost overrun—an egregious cost overrun—for this school—for this—and the building committee for this high school. And so they had to cut some things out, which happened to be playing fields, tennis courts, playing fields, amphitheater, a few things like that that they wanted for sports. And those are very desirable things. And it's a shame that they had to do it, but they had to cut it out because of the overrun. So, what happens? The School Committee decided on a little maneuver, and this is still in fight right now—going on right now. The maneuver was this: Let's request some people to set up a private organization to get donations so we can build this stuff, but we'll also get donations from the town. The town will support part of this. Well, it turns out that the organization that they set up—two of the individuals on the School Committee were married to two of the individuals in the organization—conflict of interest. Plus, what they were doing was a clear—clearly a violation of the MSBA rules. They were not supposed to be getting public funds at all.

Now, if they want—if they want to have private donations, okay. But then there's the question the town has: well, should we even allow private donations to public facilities like this? Because then we have the problem of maintenance and long-term support. And so these people, the private organization, may commit the town to something they don't want. Well, of course, they're saying, "Well, we all want these wonderful schools." Well, basically what they violated—they don't recognize—is that pragmatism does not trump due process. There are many good things that I want. Now if I choose to steal them, that's a violation of due process. (laughs) Or if I deceive somebody, or if I break the rules in getting it, I'm now using my pragmatism to trump due process.

And, as a matter of fact, that's exactly what they did in Town Meeting. They came asking for $433, 000 to fund this group, called Concord Carlisle at Play, who got this—they've got beautiful ideas for playing fields and everything—all things we'd really like to have—but they asked for $433,000 of public funds from who? The CPA that I mentioned earlier. And I stood up and just said what I told you—I said at the meeting—I says, "This is a backdoor attempt to get around the MSBA rules." I did not mention the conflict of interest between these people because that would've been a little bit too—but it's there. And they—they went into a tizzy. The guy violated the amount of time that he was given to speak. He had to be shut down firmly. They didn't want anybody to know this. And this is going to be resolved in the future, possibly by a referral to the MSBA and to the State Ethics Commission. That's a possibility. But it's this kind of exploitation of the system. It is a pragmatic thing. Postmodernism, you know? Maybe that's the way I can finish this thing off.

MK: Uh-hunh (affirmative).

CK: If you—

DS: Yeah, go ahead.

CK: If there wasn't Town Meeting, the public wouldn't get to hear your voice.

DS: 00:07:44 Well, I got up and the—I stood up and I was recognized, but I might very well have—they might have called the question before I got up. They did hear my voice, and they didn't like what I had to say.

CK: Would you be satisfied to not have that kind of public voice? Or would you find it—

DS: Oh, no, I insist—I insist that that public voice should be there, but I think that the voting on it should not be done at Town Meeting just because you have to be physically present. I think the whole town can vote on it.

CK: So you do want there to be that public discourse?

DS: Oh, of course. Discourse is absolutely an essential. How can we make any legitimate moves without weighing the alternatives?

CK: How do you want it—?

DS: But in this particular case—in this particular case—there was a scheme in place to circumvent the MSBA rules and regulations and to get $433,000 of public funds by that means—for something that was good, but in violation of the rules. And I focus on pragmatism in this particular case because—I'm going to draw on my academic background a little bit here—

MK: And then your discussion of postmodernism.

DS: Yeah. Modernism basically started with Descartes in 1600—1635 or thereabouts—when he said, "I think; therefore I am." And that's been known in philosophy as the "turn to the subject." All references of value, of worth, of reason, are turned to the subject. You are the center of the world. And for about 200 years, this was caught up in what we call—in modernity—was composed of modernism and postmodernism. Modernity was, in its earliest phase, modernism, focused on the primacy of the individual. And they ran through Nietzsche—and ran through Locke and Hume—and the rest of those guys. Until Nietzsche came along, and he says, "You're crazy. You killed God."

"What do you mean?"

"You put yourself in his place. That's all right with me," he said, "That's okay. But I don't—I want to go back to the Greek version. I mean, transvaluation that the Christians introduced. I'm going to retransvaluate back to the Greek form." And the death of history and death of—before 1962 there was only about two major works done on Nietzsche.

By the end of the ‘60s, there were over 1,000 works on Nietzsche. And that—you've seen in the 20th Century the transition starting with—of course in the arts where you saw this kind of strange modern art cult—but it was the loss of relative—it was relativism. What it was is the primacy of the self. It's taken on a new cast. It isn't the primacy of the individual self. It's the primacy of the collective. It takes a community to do these things. You've heard that someplace? To raise a child, we have to have the community. This is the collective ego that is characteristic of postmodernism. And that's ego—and it's still ego—so if the three of us decide that we can kill 50,000 Jews and get away with it to foster our agenda by whatever means, then it's okay, if we get away with it. If not, well, it didn't work. That's pragmatism.

00:11:34 Pragmatism has replaced truth in the modern world. So if you get away with it—these people can get their $433,000 by a scheme, fine. But now what have you done? You've corrupted all—you've corrupted—they've become corrupt. They've corrupted the process. They've corrupted all of the various boards and people of faith have become complicit in this exercise, so corruption now becomes widespread within the town. And unless that's just nipped in the bud, it's going to get worse. And the arguments you've heard at Town Meeting were pragmatic arguments. "Oh, I'm proud of my son; he's part of this exercise." "Oh, we've got these wonderful things." And if you want to worry about processes, another man said, "But think about what we're going to get over here. We'll get this and we'll get this." It's blatant. Blatant. It's blatant postmodernism.

Political correctness. Oh my goodness. Concord is the prototypical postmodern town. Yet is—it—because of its political correctness, there is no such thing as real right or wrong. It's what I can get away with. Maybe I can buy the town and make all the residents tenants. Maybe I can shut off all of the rest of the town from having the vote. If it works, it works—it's fine for me. And we're going to keep a beautiful town, right? Two people with two entirely different world views can do the same act. And the virtue of that act isn't the fact that they did it. It's what was the motivation and what was the foundations of that act?

MK: And what was the process?

DS: Yeah. And if we steal and we lie and we deceive, that's part of our process of doing—getting fine schools and fine playing fields and a wonderful, beautiful town--we're rotten at the core. Concord is at that cusp in its life. It's a long ways away from when the patriots stood at the bridge and said, "You know, this is wrong," and they invoked—they had an appeal to heaven. They believed that they had divinely given rights that were not to be trampled upon. Well, that's gone. They celebrate—I was in the Concord Minutemen—I fired at the bridge and I did all these kind of things along with this stuff. And I really enjoyed it. And I learned a lot about American history as a consequence. I became a historian and one of the leaders in the group. But that isn't the Concord today. You wouldn't find people meeting at the bridge to fend off—they'd join the other side. Whatever works is what goes. And if I have any complaint about Concord, it's that. It is a place where—you know, I've written weekly letters to the editor, which were basically attempts to hold people to accountability measures. And I did this for a number of years. And it got so—people so hated it, they finally prevailed upon The Concord Journal to have a policy of only one letter a month per person. And people hated me because I was pointing these kind of things out.

Now, I'm not making myself a victim, don't misunderstand this. I'm simply saying, that's the way it works. I don't expect, as a Christian, that I'm going to win most of the battles I have in the secular world. What I have to do is look at what I think real foundations of truth, justice, and mercy are and love, try to implement them—you know what it says in Micah—"What does the Lord require of you? That you love mercy, do justice, and walk humbly with your God." Now, that means you're going to die, you're going to get beaten up, you're going to get kicked around. That's not—of no consequence—because there's only one thing that really counts in the final analysis: "Well done, my good and faithful servant." That's what counts. Now, that's how—what I believe and that's why I do the things I do. I don't do it because—you know, they thought, oh, you lost at Town Meeting. Yeah, we lost at Town Meeting, and we're going to get up and fight and do it again. But I—am I optimistic that I'm—I'm going to do it and we're going to do it? No. The providence of God is at work in all this stuff. Win, lose, or draw. So we're content with that. All we have to do—all I have to do, and all of us really should do—is pursue the good as He wills it within our lives, and let Him determine the outcome. Some people will take it in the neck, politically, economically, physically, because of this attitude. And they have throughout the centuries. It's a—it's a contest between two world views: a world view which has the primacy of God at one end and the primacy of man at the other end. And those—you can't have God and man both prime at the same time. It's just not possible.

MK: 00:17:30 Thank you for stating that so clearly.

DS: Well, thank you.

MK: And it's—yeah, it's a cogent argument you offered here today, and I hope people will read this transcript and think about what you've said.

DS: Well, thank you. I hope that it'll be of benefit to somebody.

MK: Thank you very much.

CK: Thank you.

DS: You're welcome.

MK: Do you have any other questions?

CK: No, that was fine. Finely stated.

00:18:04 (end of audio B)

Back to the Oral History Program Collection page

Back to Finding Aids page

Back to Special Collections page

Home