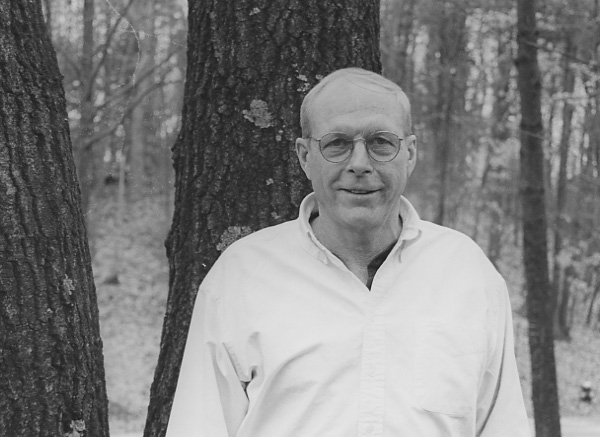

Gordon Robinson

221 Main Street

Age 43

Interviewed January 15, 1986

Concord Oral History Program

Renee Garrelick, Interviewer.

My grandmother and grandfather came from Ireland, raised their

family in Chelsea and then moved to Concord. My grandfather came to

Concord to be a male nurse at the prison in Concord.

My grandmother and grandfather came from Ireland, raised their

family in Chelsea and then moved to Concord. My grandfather came to

Concord to be a male nurse at the prison in Concord.

My grandparents met in New York City where my grandfather worked as a male nurse at Bellevue Hospital and my grandmother had come over when she was 17 years old and she was a scrubwoman at Bellevue. He was from the north of Ireland and she was from the south of Ireland and they fought about that until the day they both died. They were of different religions and we were raised as protestants because of my grandfather.

When they came to Concord, they lived on Central Street in West Concord. That was where my father was raised and they later moved to Willow Street. I spent a good deal of my childhood when I was first born on Willow Street because my father had to go into the Navy during World War II. I lived there part of the time and I lived with my other grandfather in Carlisle.

There were a lot of Irish families on Willow Street -- the Martells, the Healys, the Barrys, the Hutchinsons -- there were a pile of them around. They used to have parties out in the street all the time. I don't remember this as a kid but when World War II ended they claim my grandfather roped all of Willow Street off and the party started and it just kept going for about two days straight.

When my father got out of the service he bought the house I was raised in on Cambridge Turnpike. He had a rubbish business with a guy named George Johnson. George caught polio during the polio epidemic and died and that was when my father was concerned about the security of his family, so he went to work in the post office but he always kept the rubbish business part time. My grandparents moved to Walden Street and that's where they stayed until my grandfather passed away and my grandmother came to live with us until she died.

I never really heard much criticism about the so called real Concordians. Everybody in Concord seemed to get along fine. My grandfather was a real politician. He knew everybody and he got along with everybody and he was always doing favors for people that were having problems. He left the prison and became a court officer in Cambridge so when people were in trouble they were always calling him, "Charlie, can you fix this?" and "Charlie, can you fix that?" I can remember he would get phone calls at any hour of the night too. He was a great one for doing favors for people.

My father had the rubbish business and he took care of all of Nashawtuc Hill, the Shaws, the Farnstocks, the Lovejoys.

Concord still had a lot of farms. One of my best friends, Billy Kenney, his father (Lawrence), had a big farm (on Virginia Road). There were the Palumbos (Lexington Road), and of course, the McHughs (on Lexington and Old Bedford Roads). Andy Boy Farms was a big farm too out around Route 117-Sudbury Road area, and then over on Baker Avenue where Concord Greene is now they had a big packing house. Andy Boy Farms was a real big truck farm, mostly celery and carrots, and they used to pack all their own produce. But the farm that I remember most is the Kenney Farm because I would go down there and work with Billy on the farm quite often.

You know as a kid it was a big deal to go out and drive the tractors and the trucks, we had a good time.

You know, Lawrence, he wasn't a great one for paying you but he'd always come across one way or another for you so if you were going to do something that night he always found money for you. What I mean is, relying on Lawrence for a steady pay check, no you didn't want to do that. He was a good guy though, real good to us.

I would say the farms began to disappear probably in the latter part of the '50s and the '60s. Things really seemed to take off around here. I went to work for the power company in Concord in 1961 when I graduated from high school and there were a lot of big projects around town. That was when Thoreau Hills and the top of Lawsbrook Road were developed.

Just prior to coming to work at the light department what they called the cattle grounds down around Elsinore and Belknap Streets were all developed around the Southfield Road area. Conantum was another big project that was completed during the latter part of the '50s. And you go out Monument Street now and that land out there is all houses.

The light plant had a lot of Irish people working for it. When I went to work there, Dinny Horn had just retired but it was the McKennas, the Barretts, the Sheehans, the O'Neils and the Ryans, so it was basically pretty Irish.

Concord was still a small town where neighbor kind of knew neighbor. My father and grandfather I would say probably knew just about everybody in town at that time or everybody knew them. And as a kid you go to high school and you knew all the kids.

When we got to junior high school, that's where the kids from Concord and the kids from West Concord finally got to meet. During the first few weeks of school, there was quite a show down there just to see who the toughest kids were. The kids from West Concord were definitely tougher than the kids from Concord, they could fight a lot better.

West Concord I would say was just about all working class people in those days. You know, in Concord it was in the Belknap, Elsinore Street area where the working class lived. Down where my parents were on Cambridge Turnpike, everybody there were working class. There were the Marabellos, Joe and John Marabello lived in Concord all their lives, the Rusts, the Murrays.

Housing really began to change in West Concord with Thoreau Hills. At the top of Lawsbrook Road, in the Shagbark, Sorrell Road area, that land was all sandy and wasn't used for much of anything and then they developed it into house lots. Down in the Lawsbrook Road area where Wedgewood Common is now, just across the street, West Concord had their own dump at that time. Up around Sorrell Road, there was a pig farm at one time too.

I started school in what they called the portable building for kindergarten which would have been next to the Peter Bulkeley. Then they built the Alcott School and I went through grade school there. After grade school, I went back over to Peter Bulkeley for junior high school and then went to the Emerson School for high school and in 1961 they opened up the Concord-Carlisle Regional High School. I was the first class to graduate. So I just about hit all of them.

Teachers at the high school who influenced me were John O'Connell right at the top of the list and Fred Tobin and Jim Hayes. John O'Connell was gym and the football coach, Fred Tobin and Jim Hayes taught history.

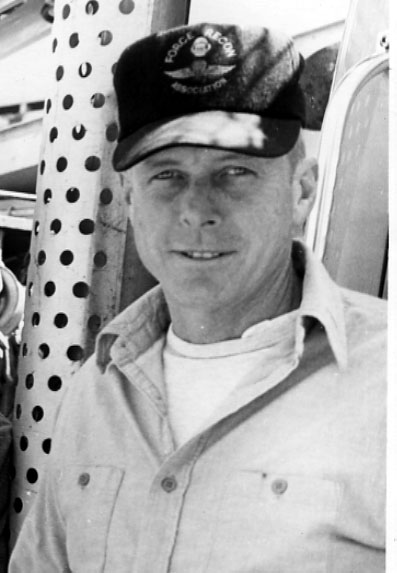

When I graduated there wasn't an all volunteer service so you were going to get drafted if you didn't join. All of my friends went in, in fact I had two or three friends that were in the reserves while I was in high school and once they graduated, they went off to the navy. Then I got out and went to work for the light department. When I found out I was going to get drafted I thought I was going to go into the air force, but when I saw the marines and their uniforms go by, I joined the Marine Corps. Plus Fred Tobin, my history teacher, was an ex-marine and I really respected him a lot and he kept bragging about what the marines did so I figured I would give it a whirl. What an experience that turned out to be!

I went to Parris Island and from there I went to Camp Lejune and to Fort Benning, Georgia to jump school. I went around to different islands in the Caribbean on some practice missions, and then came back to the States again. They were looking for guys to go to Okinawa so I volunteered to go over there. I was assigned to a motor transport outfit which I didn't care for very much because of my previous training and that's when I volunteered to go into a reconnaissance outfit in 1965. I stayed over in Vietnam until '66-'67.

A reconnaissance team was made up of four people usually, unless there was a real long patrol where they may take out eight or twelve guys and there would be relay stations set up on the patrol. We would go so far out that you just couldn't communicate back to the main base so you would set these relay stations up so you would have some kind of communication back to headquarters. We usually would go out for six days and then come back for two depending upon what the mission was.

Some of our patrols would actually go into North Vietnam but a good percentage of them would be right along the border. We worked out of an area called Dong Ha and another area called Phu Bai and I was down in Da Nang for a short period of time too. We worked in what was called the I corps area. We would run missions basically for any marine infantry unit that was going to go in there on an operation. We would go in and find out what was actually the size of enemy forces in there. It wasn't our job to make contact with the enemy which was a good part of the job, the infantry would go and actually fight the enemy. With four guys you didn't really want to get into much of a fight but it was interesting and got a little hairy at times.

I was with recon group bravo so we would have maybe fifteen teams at the most when we were up at full strength. For one reason or another there were always teams that just weren't up to full strength so they'd have to keep swapping guys around all the time. But it was interesting because you went out and did your job and the guys I was working with were highly trained and professionals and we didn't have any problems with drugs. Everybody in the outfit was strictly a volunteer, they wouldn't take you if you didn't volunteer for it. So it wasn't like some of the outfits you heard about in Vietnam where there were a lot of drug problems.

And the other thing I had going for me, I was over there in the very beginning of the Vietnam War, as far as American troop involvement, and I left there just as things really took off. When I did extend over there, I was wondering if I had made the right move because things were really getting bad. And when I got out of Vietnam, I came back to El Toro, California where I was discharged and I just came home and went back to work for the light department.

I was 23 when I was in Vietnam but I was actually 21 when I went into the marines. So I was an old man actually, most of the guys were all 17 or 18 years old.

Because you're in a reconnaissance team, you don't bring tents or anything of that nature. You had the clothes on your back and a pack. I was a radio operator so I carried a radio, a spare battery for the radio, all the food and water and ammunition, and the hand grenades that I felt that I would need. You had to use a lot of discretion too because you were out there for six days so you didn't want to run out of food or water. You didn't get resupplied. A reconnaissance team would go in and nobody ever came to see you again until it was time for you to leave. So you had to survive off the land and anything that was on your back.

When it rained, you just sat in it and you slept in it. We never believed in using ponchos or any kind of rain gear because first of all they make noise and when you were supposedly trying to sleep at night you never want anything over your head, you always wanted to be able to hear what's around you, so we just didn't take any in. We'd just lay on the ground and went to sleep. But you can't honestly say that you slept in six days, I mean you say you slept with one eye open, it was wide open. And in the jungle, it's real dark. I used to hate to see the night time come, hated it with a passion. You'd sit there and even if there's nobody out there, your imagination just does wonders, scares you half to death. If you'd just sit there long enough and look out into the darkness, it could really get to you after a while.

If you talked, it would always be in a whisper in a reconnaissance team and we used a lot of hand signals especially if we were in areas where we felt or we knew we were in close contact with the enemy. Because a lot of our missions were right in enemy territory, or just outside VC villages, we even slept in VC villages and they didn't know we were there.

Once your mission was compromised, you were extracted or in other words, they took you out of there because the element of surprise was gone then. And the other thing too for the safety of the reconnaissance team, a four-man team just isn't equipped to go fight a VC platoon. The only weapons that you had were the ones that you actually had in your hand and the ammunition you had with you so you couldn't last too long in a firefight. You could call in for air strikes or artillery missions if artillery could reach where you were, but in most cases if we ran into trouble we had to get air strikes.

So from the time you made contact with enemy, you'd have to wait until the jets came on station or the helicopters or whatever was going to be your close air support for that mission. Air support was great to us but it's like if you have an accident and you're waiting for the ambulance to get to the house, it seems like it's forever and a day before it gets there. The helicopter pilots in Vietnam were unbelievable, they pulled us out of a lot of tough spots and I have a lot of respect for them. It didn't matter if they were marines or not, but in most cases it would be marine pilots but whether they were marine or army, they would always come. If they knew there was an American in there, they would always come in and get you.

When we ran reconnaissance patrols down around Da Nang when I first got there, we dealt strictly with VC or Vietcong, who were basically a bunch of farmers, very unorganized, didn't have much as far as weapons, and they were just causing a lot of problems. But when you moved up north along the DMC and then as the Vietnam War progressed and the years went along, the North Vietnamese moved down and they were trained military soldiers and they knew how to fight and how to work in the jungle. They were good soldiers, we learned an awful lot from them. It cost us a lot of lives to do it.

The Vietcong didn't have much as far as weapons, you know they had to rely on what they could pick up or what the North Vietnamese armies would give them but the North Vietnamese armies, the weapons they had they were going to keep themselves, they weren't going to give them to the peasants to fight with.

You figure you go out on a mission and there's three other men with you so you've got to be close with them. If there was a problem with anybody in the team, you just ask to get off that team and get put on another one. Or if you didn't want to be in recon anymore you just went in to see the first sergeant and tell him. Of course, your next destination was the infantry so I don't know if that was very good. You could get out of recon at any time, it was strictly volunteer.

You had real real close friends, friends like you probably never have ever again because you relied on them so much. But then as things wore on and I gained more rank and had more responsibilities, you tried not to get too personally attached to these guys because you'd already experienced what had happened to some of your other close friends. So, it's like everything else, you had to harden yourself. You had to harden yourself to a lot of things that happened to you in Vietnam and that was just survival.

We would go on what we called an overflight before we would go on an actual patrol so the team leader would usually go out and then usually an officer would go with you that was from the intelligence division and you would fly over the area looking for prominent terrain features, because when you get in the jungle you can't see anything. A lot of times you have to climb trees sixty, seventy feet in the air just to try and find that bend in the river that is supposedly on the map. It was important that you knew where you were too because if you had to call in an artillery strike or call in for close air support, they've got to know where you are. So that was a big concern all the time to know your exact location.

The VC would, just like everybody else, need water so they'd build their camps near water or within walking distance of it anyway. The I corps area was real mountainous and a lot of heavy jungle with a lot of small streams and rivers running through it. So anywhere there was water close by was suspect that there may be a VC village or a North Vietnamese regiment or whatever in that area. You knew they would be in close proximity of where the water was.

When I returned home, I was real nervous. For 18 months I spent basically working on my nerves. That was what kept you alive over there, you had to stay sharp all the time. And when you get back home, I mean you hear the Vietnam veteran talking about just getting off the plane and all of a sudden he's in the good ole USA again, it's quite a change. First of all, when I went over to Vietnam, I went from the peace time Marine Corps and I went over to Vietnam on a ship, then I got into a combat situation where the whole concept of the Marine Corps, spit and polish, was lost. Now we had a job to do and they didn't pick on you about how your hair was cut or anything. All they wanted you to do was to go out and do your job. Then you get back to the states and my first entrance to the states was El Toro, California and I was going to be discharged there. I was walking with a friend of mine and we had gotten off the plane at 3:00 in the morning, now it's 7:00 in the morning and the first thing out of this MP's mouth coming towards us was "Hey, marine, roll down your sleeves!" And we could tell by just looking at this character that he had never been in Vietnam so I just figured I'm getting out of the marines, I'm not going to give this guy a hard time, I'm going to do what he tells me but my friend didn't see it that way. So he walked over to him and said "You ain't man enough to pull down my sleeves!" We had a little problem there for a while but they got it straightened out.

Then when I got discharged and got home, I was fortunate I had my job back, I wasn't like a lot of Vietnam vets who couldn't find work, I wasn't hooked on drugs. I drank a lot and went out and partied all the time, and really lived in the fast lane for a while.

I was real nervous for a while. If you just heard a car backfire, you're really looking over your shoulder and kind of jumping back. I know when I first went out with my friends a few times that hadn't been in Vietnam, I'm sure at times they were looking at me like he's out of it. After a while, it's like everything else, you just kind of get back in the mold of things and go along with life.

But one thing about the Vietnam experience that has helped me a lot is when things have gone bad later on in life, I look back to the things that happened in Vietnam and I still haven't had any experiences that have been as bad as some of the ones that I had to deal with in Vietnam.

I was in an outfit that was highly motivated, all volunteers, so basically you could say we were brainwashed. We believed that we were the best at what we did and we thought that everybody basically was the way we were. We went out and did our job and came back to base and went out and had a few beers and really didn't talk much about winning or losing the war as long as we came back with our four-team in one piece, that was all we were concerned about. So basically, this business about God and country, what it boils down to is survival of the fittest, I mean you just worry that you're going to get back in one piece. But the other thing too, especially in reconnaissance team, you always worried about those three other guys. You were like one so as long as we all came back and if we had a good mission and we had done our job real well, you know we would go out and party, we didn't really even look at the whole concept of the war.

Of course, this was the beginning of the Vietnam War too. Later on as things weren't really going our way and after they started taking a village and then two days later they would lose maybe a hundred or two hundred guys to take an area and then pull out a week later, then people were asking a lot of questions. And even when I got home, I'd look at the TV and I'm wondering why do they do things like that, so I could see why people were getting disenchanted with the thing. But basically what it boils down to is if you're going to get involved in a war, plan to win it. Forget about police actions. I have a son here now that I'd like to see go into the service but I never want to see him go to war. I'd like the service part of it, I think it's a great experience for a kid to meet other people and see how other people live and get to travel around the world and let Uncle Sam foot the bill but as far as going to war, no I never want my son or daughters to ever have to go through some of the things I went through.

When you were in Vietnam, you were in their backyard so when you were fighting over there, you had to basically survive over there, you had to kind of watch them and see the moves they made and just kind of put it in your memory bank and say "well, if they do this, there has to be a reason for it," and I think that's a lot of the reason a lot of us made it over there. Because after a while, we got to fighting the way they did.

The North Vietnamese were very good soldiers. They did so much with so little. And we came over there with all these big fancy weapons and basically a four-man team just went out there the way the North Vietnamese did, went out there with a rifle and some ammunition. But you just had to outthink the other guy and outsmart him. If we got ambushed, we started shooting and started running to try and lose them. You wouldn't get down and try and shoot at one person because first of all in the jungle, you very seldom ever saw what you were shooting at. I mean, all of a sudden you knew say on your right flank there was somebody shooting at you and you would take your weapon and put it on full automatic and spray that area and hope that you knocked them down. We occasionally would take snipers out with us and we would set up security for them and they would just lay on a hill somewhere. There would be a trail going by and they had these powerful scopes on their rifles and would sit there and just pick away at people. Now that was a one-on-one deal but very seldom in Vietnam would you actually sit there and just see the person face to face and shoot him.

In the latter part of my tour over there the food supply was getting down because first of all we started bombing the hell out of the place and between napalm and bombs and the troops running through the rice patties, they had to be getting low on rice. Plus the North Vietnamese would come in and if the villages wouldn't go with the North Vietnamese, they'd just burn off the rice crop, or if it had already been picked, they would poison it by throwing gasoline or something on it and ruin the whole crop. Plus you go into villages where the North Vietnamese had gone in there and if they didn't cooperate, they'd kill the chief's wife or rape her and kill all his children and in some cases kill him and in some other times they would leave him alive and let him witness all this.

Depending upon what the mission was, we would sometimes take an interrogator right with us, not too often. From my own personal experience, I didn't trust the interrogators that we had with us. I wouldn't trust them at all. I can't speak Vietnamese, well, a few basic words, so you never knew what they were up to. If we did capture a prisoner, we'd bring him back to headquarters. That was a different operation then because we had a lot of our own intelligence people there with higher level Vietnamese and they would be doing a lot of the interrogations. I can't say too much about capturing prisoners because our batting average wasn't too good on capturing prisoners. We tried a few times but we failed.

The biggest job of all that we had was to make sure we came back in one piece.