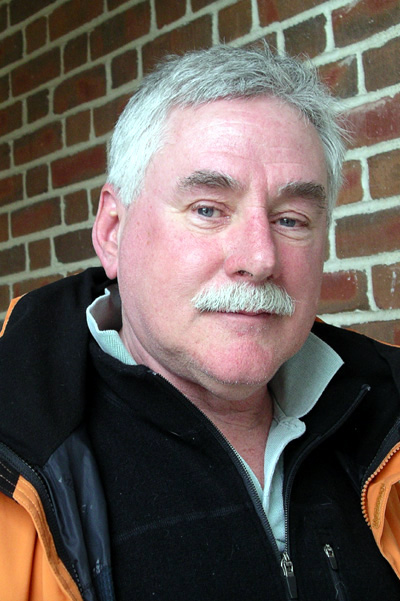

Donald Prentiss

Interviewer: Carrie N. Kline

Date: April 20, 2011

Place: Concord Free Public Library Trustees' room

Transcriptionist: Carrie N. Kline

Click Part 1 — Part 2 for audio. Audio file is in .mp3 format.

Michael N. Kline: Okay, today is April 20th and we're at the Concord Free Public Library. I'm Michael Kline. And Carrie Kline is here with me. It's a grey, cold day. It makes you wonder if spring's ever going to come. And maybe you can introduce yourself. Say, "My name is."

Michael N. Kline: Okay, today is April 20th and we're at the Concord Free Public Library. I'm Michael Kline. And Carrie Kline is here with me. It's a grey, cold day. It makes you wonder if spring's ever going to come. And maybe you can introduce yourself. Say, "My name is."

Don Prentiss: Yeah, I'm Don Prentiss.

MK: Okay. And your date of birth?

DP: Is 9-5-46.

MK: And maybe you'd start off and tell us about your people and where you were raised.

DP: Okay. Well, I grew up in West Concord. And my dad grew up in West Concord also. My grandfather came to Concord as young man, and he lived on Walden Street. His father passed away. And so he lived with the Bartlett family. And his mother, who was Eliza Pennyman, her father ran the Wright Tavern. The church bought the Tavern, and they hired him to run it. So there is a history of the Wright Tavern, and in it it talks about Otis Pennyman being hired to run the Tavern. But he wasn't much of an innkeeper. So, I think it was--. He ran the Poor House at first. So they thought he might be able to run the Tavern. But he didn't do a very good job, from what I understand.

MK: The Wright Tavern?

1:32

DP: Yes.

MK: What and where is that?

DP: The Wright Tavern is in the center of town. It's where the British soldiers had their command post the morning of April 19th. And I guess at one point it was kind of a downtrodden inn, not very well liked by the community, and I guess it, as some point it became available for sale and the church bought it. And they've owned it ever since. And that's when they hired my grandfather, Otis Pennyman, to run it. And

Carrie Kline: He had run the Poor House before that?

DP: Yeah.

CK: Talk about that.

DP: I don't know much about it, really, just that he ran it. And it describes it in this book about the Wright Tavern. But I don't know much about it. But there used to be a building across from the Walden Street Fire Station that I always, everybody always called it the Poor House. And at one point it was torn down, and now there's a residential home there. So there must've been people at some point in the late 1800s who were considered poor and they needed a place to live. It's—I don't think there's any more poor people in Concord because the houses seem to be pretty lavish. And I bought a little house on White Pond years ago and my wife and I are quite comfortable there.

MK: Is that within the town limits?

3:16

DP: Yeah. It's in South Concord, what they call Nine acres Corner, or White Pond. And--.

MK: So, Thoreau writes that the boys in town were always there first. It didn't matter what was going on. If it was the blueberries were ripe, and he was going out to pick some blueberries—

DP: Yeah.

MK:--he found that the boys already had been there. If it was a fire somebody reported, he went to the first. The boys were already at the fire. The boys always were a step ahead of everybody.

DP: Yeah.

MK: I wonder how that was in your generation.

DP: Well I don't know what you mean, by boys.

MK: Just the boys, kids growing up.

DP: Just--. Oh yeah?

MK: The boys, gangs of boys.

DP: Well there seemed to always be different gangs around town, but not typical of the gangs you see today.

MK: No, no.

DP: There the Italian section behind the Depot. That was the Depot gang. And but you talk about blueberries, when I was a child along Old Marlboro Road and what now in Mac Arthur Road was loaded with blueberries. And my dad used to take a fruit juice can and put a string on it. And we could go out and fifteen or twenty minutes have the can full of blueberries the size of a dime. And they were all wild blueberries, but you very rarely see them anymore around town.

MK: Hmm.

DP: And--.

MK: So what bunch did you run with or lead?

DP: I didn't really run with a gang. I just sort of, I enjoyed being with everybody. I had some friends what were-. Well I had some friends that were--. Well I wasn't the best of students, but I had some friends that were horrible students. But then I used to socialize with some of the more intellectual, I guess you'd call them, or wealthier kids in town. I just had that ability to have a good time with just about anybody. My best friend is Doug Macone, and I met him at the Junior Sociables, which they used to have at the Scout House. And that was on Saturday night. And they always had a horrible band, but it was something my parents would drag me to. And after fifteen or twenty mines Doug Macone and I were gone. But we would come back towards the end of the program, so our parents could pick us up. But. You know, just--. It was really--. Then, it was horrible. But I think about it now, and it was kind of exciting back then. But--.

CK: Where'd you guys go when you took off?

6:02

DP: Just downtown, down around the Milldam, just stay out of sight, until we figured the program was over. And then we'd come back and--. But the band was always terrible. It's not today like--. I guess it was a professional band, but it wasn't--. It was an accordion and a bass player and a saxophonist. Just doesn't make for great music I don't think.

MK: So what was there for boys to get into growing up around town?

DP: In Concord? Well there was a teen center, but what I enjoyed about Concord was the history. I mean there was always some place to go and see the history, like the Old Manse, or the Alcott House, or just great woods. We had Walden Pond, White Pond. We canoed on the river. And I worked for George Rowan for a couple years as a teenager, and I used to rent the canoes on Saturdays and Sundays. And towards the end of the day my buddies would show up, and we'd all grab a canoe and canoe up and down the river, tip each other over. We used to--. And as we got older, one of my friends had a motor boat. And we were all eighty pounds soaking wet. And we'd water ski up the river to Fair Haven Bay. It's just, there was a lot of stuff to do in town. And there was horses. There was Elm Brook Farm. There was Victory Lee Stables. I still ride horses today. I--. We've been riding with the Concord Independent Battery for forty-five, forty-three years, and--.

MK: The Concord Independent Battery?

7:44

DP: Yeah. Concord has their own artillery. And one of the reasons the British came to Concord in '75 was to look for brass cannons. And there were, reportedly that the Colonials had, and they were hidden out, supposedly at Barrett's Farm on Barrett's Mill Road. And that's one of the reasons they came to Concord. All the guns were disassembled, from what I understand, hidden in the fields. And I don't really know what quite happened to them after that, but I do know that Concord always had an artillery company. And it was originally called the Concord Artillery. And in 1804—I hope my history is correct—the Adjutant General wanted the guns back. And the Town refused to give them the guns. And they went to the Legislature, and the Legislature gave the Town permanent custody of the cannons. And the two original cannons, one is in the Bunker Hill Monument, and the other one is up at the Visitor's Center on Liberty Street. The original, the two bronze cannons that the Town had for a number of years, then they were condemned as being unfit for use. So they're in Doric Hall in the State House on permanent display. And the state gave the Town two more cannons, and they're here in the Gun House on Lexington Road. We take them out every April 19th and fire a--. Well we do the parade, which was on the 18th this year. And then we did the Dawn Salute on the morning of the 19th. And this has been going on since 1804. My grandfather was involved with it somewhat, but my father never had any interest. But like I say I've been doing it for forty-three years.

MK: Forty-three years. That would've made you about twenty-two or something when you were--..

DP: When we started, yeah. 1968.

MK: How did you--? Was there an application process to get in? How did you . . . ?

9:55

DP: Well I knew Dick Ryan who was with the Fire Department at the time, and he was a member of the Battery. And Lawrence Kenny, who had a farm on Virginia Road, found out I had a horse and I knew how to ride. So I was sort of told that, "You're going to ride with the Battery." So I said, "Great. Fine. Excellent." Because I used to, on the morning, go up and watch them fire on the 19th. And I always thought it would be neat. So I was sort of invited to ride with the Battery. And I bought my first house. Of course the horse had to go. Couldn't afford both.

MK: Did they issue you a uniform?

10:38

DP: Yeah, We go out and get our own uniforms, but the uniform isn't correct for the period of the cannon. The cannon's a model 1845 I believe. So that was the year they were made. And my--. Well I guess what happened is over the years the uniforms changed with the period. So there is a photograph in the Colonial Inn of the Concord Independent Battery out front that was taken in 1875. And their uniforms are more Civil War-type. Then they did another--. So 1870, yeah 1975 they did a picture of the Battery again in front of the Colonial Inn, to replicate that hundred years between photographs. And the uniforms are kind of typical of the First and Second World War. The campaign hat, which is sort of the mainstay--. It was adopted by the Battery. It's not typical of an artillery of that period, of 1845, but they kept it, because it was readily available. And the uniform is a khaki brown. I think the original uniform was quite striking. I mean it was like a jacket with tails, and stripes, and hat with plumage, just pretty spectacular, but not practical for today.

MK: So describe the whole ritual. Is the cannon loaded once it gets to the site, or--?

12:15

DP: Yeah, what we do is the guns are maintained by the Concord Independent Battery, but they are owned by the Town. So what we do every year is we go to the Town and apply for a contract. We have a contract with the Town. We'll maintain and fire the guns at different Town ceremonies. And what we have to do after the first of the year is everybody has to do twenty hours of training before they're allowed to be on an active gun crew. So we practice like Wednesday night for two, three, four hours at a time so everybody can get their twenty hours, because you have to be trained and certified in several positions. Then the first outing for the Battery is April 19th. And what we do is we participate it the parade, but we go a different way than the--. The typical parade goes up Laurel Road to Liberty Street, but we go Monument Street to the Battlefield at the Old Manse. And we set the guns up there, so while the parade comes down through the National Park and across the bridge, we fire a number of volleys. And then what we do is we join in. We hitch up and join in with the end of the Parade and come down through town. And this year the Parade was on the 18th. So the morning of the 19th we do the Dawn Salute at 6:00 a.m. And we fire several rounds. Typically it was 21, but due to the fact that regulations require that we spend I think it's three minutes between rounds, the Minute Men fire. We fire a round, and then the Minute Men fire a volley. And we fire a round. They fire a volley. And we do twenty-one that way.

CK: So you're being the British?

DP: No, we're just being-. It's called a Dawn Salute. And we're not--. I doesn't-. It has to do with the Battle, the history of the Battle. But we're not sides. It's typically the Minutemen, who are local; it's a local group that participates in it. They do a reenactment, but not always. Now Lexington does a reenactment in their Square. We used to do a reenactment at the North Bridge, but time doesn't always allow it. So it's just--.The Dawn Salute is just that. It's a twenty-one gun salute they do on the morning of the 19th and have for hundreds of years without stopping, other than during World War--. Like World War One or World War Two they didn't do the Salute, because powder was scarce.

MK: Can you describe how the cannon is loaded? Is it a black powder cannon?

DP: Yeah. It's what they call a six-pounder. And what we have to do is we take the powder. It's this b--. We're allowed so many ounces per inch of bore. So we take that calculated amount, and we put it into a, aluminum foil tube that we make. It's basically formed around an old Skippy peanut butter jar. You get--. It's approximately the right size. So we do the sleeve. We put several ounces of powder. Then we do another sleeve with several ounces of peat moss. And that goes on top; and then it's all twisted together as one charge, and it's typically six toe seven-inches long and just under four inches in diameter. So we make up several rounds prior top the event. Then we--. So typically on the morning of the 19th, we go through a ritual. Everybody's given an assignment, and there's two gun crews. And Number One is the rammer. Number Two is--. He puts the powder in the gun. Then there's Three and Four. And they typically take care of the charge, or the--. What we use is a thirty-two blank cartridge that fires the charge. We use what they call a wild mechanism. It's a little mechanical device, because originally they used a device that was called a friction device. And it had something to do with a chemical called fulminated mercury. And it wasn't consistent. It didn't always work. It was susceptible to problems. So what they did is they changed the mechanism to what they call a lyle mechanism. That was typically used by the Coast Guard and Naval vessels to fire a lanyard from ship to ship, which is a light rope. And they would pull a heavier rope across. So it was just a more substantial device to fire the guns with. So typically Number One, who was the Rammer, would take what they call a sponge. And he would sponge out the barrel. Then he would put the sponge away and get the rammer, which is--.What we use today is just a cardboard tube in case there's a pre-ignition the tube just sort of disintegrates, and it doesn't--. The theory is that it won't hurt anybody. So when he's ready he taps the barrel with his rammer. The powder monkey brings the charge down, hands it to Number Two. Number Two takes, swings around over the wheel, and slides the charge into the muzzle of the gun. These are what they call muzzleloaders. So it has to be loaded from the front. So, then the rammer rams the charge in. Then Numbers Two and Four—Three and Four—put the thirty-two blank charge in and get the firing mechanism ready. And then when the gun is ready, the gun captain, the Gun Lieutenant, or gunner, will let the Captain know that the gun is armed. He'll tell them to proceed. Then they get ready to, get into a position where they can fire the cannon. And then at some point the Captain is directed either by portable radio or it's just a gut feeling, because typically the predetermined plan doesn't always go the way they thought it would go. And we're supposed to typically fire a round after Taps and Echo. But we can't always hear it, so at some point somebody says, "Number One gun, fire!" and off it goes. So if we're correct, great! If not, well, we'll load the other gun and get ready for another round.

So typically we fire several rounds. And as the parade comes across North Bridge, and they move down towards Monument Street, we hitch up and pull in behind the Parade. And we still use horses to draw the cannons.

MK: Hmm.

CK: Whose horses?

19:58

DP: Well we get them from different places. Typically we used to get them from--. Years ago they used to get them from, the prison used to maintain horses. And they'd either get horses from the prison--. Excuse me. Or there's a farmer on Barrett's Mill Road named McGrath [Phone rings.] That's me. I'm sorry.

CK: This is fun.

DP: Oh, good. I'm glad.

MK: So they typically--. You were saying.

CK: First from the prison.

DP: Yeah, we get horses from the prison. There's a farmer on Barrett's Mill Road named McGrath. He used to have horses. And then when I joined the Battery they typically got the horses from Lawrence Kenney, who had a farm on Virginia Road. He always had one or two teams. And we'd get horses from Nick Roddy further down Virginia Road that had stables. And he had eighty to a hundred horses. And he always had two teams. Because the Town used to contract with Lawrence Kenney, who was, had antique wooden snow plows. And we used to do the sidewalks with them. Up until probably the early '80s is when he stopped, because he just, he couldn't do it anymore. And I used to help him out or I'd work for Nick Roddy and we'd plow sidewalks. Now they have the modern bombardiers and stuff. But we used to do it with horses up until the '80s.

MK: [Whispering] Wow.

CK: Why?

21:38

CK: It was a tradition. You know, Lawrence Kenney used to do it. I mean there wasn't a lot of money into it, but it would pay for the feed and hay for the horses, and it kept them busy during the winter. Because typically there isn't a whole lot of work for a draft horse in the winter in this day and age.

CK: Did they work in the summer? Were these real . . . ?

DP: Oh yeah. Lawrence-. Well Nick Roddy used to have, do hay and sleigh rides during the, especially during the fall and winter. But he's do them any time of the year.

CK: What was his name?

DP: Nick Roddy.

CK: Spelled?

MK: R-O--?

DP: R-O-D-D-Y. And he used to--. He had classes, and on the stables he had owners. He would stable horses for different owners, but he would be involved in trucking his horses to different events through New England. And, plus he had his own school horses. And he used to have classes like three or four nights a week. The beginners like were Tuesday night. And then the professional riders, the people that were really into doing events and stuff like that would practice other evenings. And then every Sunday he'd have a, what they call a trail ride, which would be out around Walden Pond, over through Lincoln, and back into Concord. And there'd be anywhere from a dozen horses to thirty or forty horses. And there were different groups. Because they would--. Sometimes they would split up, so more professional riders would take a more difficult trail, where you'd come down an embankment, and there'd be a jump. And you'd have to take the jump and make a sharp turn, otherwise you were going to wind up in Walden Pond. But and then there were--. I usually took the easy ride. But I still ride. I still go out to Arizona and ride. I just got back. I spent a week in March in Arizona.

MK: [Whispering] Wow.

DP: Just--.

CK: Not much call--. I mean he wasn't teaching people to work horses though, or was he?

DP: No. No. The draft horses were more of a--. Well for Nick Roddy they were part of how he kept the farm running, because they did make good money doing the hay and sleigh rides. They had these big pungs, they were called.

CK: Called what?

DP: It was called a pung.

CK: P-U-N-G?

DP: Yeah. And it would be maybe a dozen passengers plus the driver. And we used to go all through the woods around Concord and Bedford into Lincoln, Hanscom Field. Because typically at night it was closed, so there was always different roads that you could use. It was pretty good. A little bit of hay. Everybody's bring a little something to drink to keep warm.

MK: So a pung is like a spring wagon?

24:39

DP: Well no, it's like a big sleigh.

MK: Oh, a sleigh.

DP: Yeah. And it had--. There were two sets of runners, and they were chained together, so that if you turned one, to the left, the rear runners would turn to the right. They had a cross chain. And every once in a while that'd break, and the whole thing would kind of go askew, and we'd have to try and get a repair link on it, or everybody had to walk back to the barn, and we'd come back and get the pung the next day. It's--. You know a lot of that is gone now. I miss all the old dairies. There used to be three or four dairies in town. They're all gone. And as a young boy I used to go over and watch--. Now I can't think of his name. Um. There was Madison Farm and Denomandy and Verle.

Oh, Fred R. Jones was the one that was close to my house. And I used to go over in the morning and watch him milk and pasteurize the milk. And they'd bottle it. And it was all local. So did DeNormandie and Verrill had quite an operation because down here where Dunkin' Donuts is, and the rest of the building that's attached to that was Concord Dairy. And the milk would come in there and be processed, and then it would go into milk trucks and be delivered. I can remember as a child being, sitting in the kitchen. And the milkman would come in and he's put the milk in the refrigerator. And then he'd leave. If we were up. If we weren't there it would go into a little insulated container. And he'd pick up the empties. But he was an old friend of the family's so he used to just come and put the milk in the refrigerator, and on his way out he'd grab the empty bottles, and he'll say hello. And once in a while my mother's offer him a cup of coffee. That's something you don't see anymore. Nobody wants anybody in their house.

And there used to be, in West Concord, where the West Concord Plaza is, there used to be a gentleman there that had a--. There was a large barn that belonged to the Derbys. And they had sold the property. But he had a store in the barn. It was called The Yankee Trader. And he sold used furniture and clothing and penny candy and ice cream. So that was a popular spot for us. But. And I can remember--. You don't mind if I just ramble on?

MK: Oh please.

CK: . . . great.

MK: This is great.

27:24

DP: I remember one night my dad came home, and he had two passes to the circus. And I didn't know the circus was coming to town, but somebody came in and said, "The circus is coming on July 22nd" and wanted to put--. My dad had a storefront on Comm. [Commonwealth] Ave. in West Concord. And they put these two posters up in the window, so they gave him two passes to the circus. And it was the Hunt Brothers Royal International Circus. Concord. It was at Rideout Field in West Concord. It's like a series of baseball diamonds and soccer field, and . . . .

MK: Called? Called?

DP: It's called--. I just t--. I can't--. Why can't I remember it? Rideout.

MK: Spelled?

DP: I'd have to write it down. But anyways, Mrs. Rideout gave the property to the town for this field and gave it to the children, so it's this series of baseball diamonds and--. That's, so that's where the circus set up. And I had never seen anything like it, because it was--. Now I thought there'd be a big circus train coming into town. So I sat by the Depot early that morning, and no train, no train. Well it came in on a truck convoy from the other side of town. But it was the most

amazing thing I'd ever see because of the-. They actually set up a big top tent, and they used elephants to raise the tent. And it was just amazing to see, because the elephants just stand there. They had this harness on. And they'd hook these huge ropes to it. And they'd pull--. These massive poles would come up, and they'd stop. And then the tent would come up on the poles. And then a group of people would go around, and they'd put smaller poles on the outside or perimeter of the tent. And then they had a gang of guys with stakes. And they'd set the stake. And these guys would stand around the stake and drive it. And it wasn't--. It was like a machine. Everybody--. It was a constant swing of the hammer. They would stake, but there was a guy right behind him on the other side would hit it right after him. And then another guy in the other quarter. There'd be like four guys, four or five guys doing this at the same time. And they'd drive that stake into the ground within minutes. But it was quite a show. I missed the show. Because the tickets were for the matinee. I went to the evening show, and this guy said, "Oh, the tickets are no good." So we tried to sneak in, but that didn't work out either.

CK: So your show was seeing the set up?

DP: Yeah. Basically. You'd see it on a TV show or a movie or something. To see it in real life was completely different. It was amazing to watch.

MK: It sounds like you were a kid who was much more impressed with animals than you were with machines.

DP: Oh, absolutely. Well, I am--.Well my wife calls me a motor-head, because anything mechanical I'm fascinated with. And I suppose that's what, where the interest comes from because I was always watching the trains go through town. Or I work on old cars now, which is kind of a sideline. Different people have antique cars, and I make minor repairs and stuff for them and help them keep them maintained. And it's just--.

MK: So did I hear you say your dad had a storefront?

DP: yeah, he was an electrical contractor. And so my grandfather had a house and barn on Commonwealth Avenue, and that's where they ran their business out of. After my grandfather died, my dad took over a little storefront on Commonwealth Avenue. But it was basically just to store supplies in.

CK: What's an electrical contractor?

31:32

DP: He was an electrician. So he did electrical repairs. Excuse me. But he decided to do commercial work. And he did a lot of pretty special jobs around, all around New England. But I told you about renting canoes at Southbridge Boathouse. And before I left there I wound up as a mechanic working on outboard motors and--. That led me to something else. There used to be a ski-binding manufacturer in West Concord. And Ott Overgaard came to Concord from Norway as a young man. And he worked at Middlesex Ford, where Tuttle's Livery is, used to be a Ford Dealership. And he worked there, but he came up with an idea for a safety ski-binding. Because typically there was a ski with a strap that ran around your foot. So if you fell down, something broke. It was either the ski or your leg. So he developed a safety binding. And he made the tooling by hand and developed it into a multi-million dollar business. And I worked for them for several years after school, counting screws and putting them in little plastic bags, to when I left I was a tool and dye maker. I used to be in charge of like quality control. I had to check all the parts that were coming out of the machines to see that they still met tolerances and so forth. But the company failed after--. They just couldn't keep up with some other manufacturers. But they developed the first safety ski binding.

MK: Was there a patent problem that somebody else got the patent?

33:31

DP: No, it wasn't so much as their design was very--. It was a cable release system, where other companies came out with a heel device that you stepped into and it would lock. But it would also, in the event of a fall, would release. So they tried to develop something similar, but it just never really caught on. And they tried some other products like shoe trees to put your ski boots in. But then somebody came out with a bag type of, basically a bag that you'd put your ski boots in, and that seemed to be more popular. They just couldn't catch up. The development was so quick, and the industry was changing to rapidly that they couldn't keep up.

MK: So.

DP: And they sold out to a couple other guys from New York City. And they tried to resurrect the company, but it just never really recovered.

MK: So we're talking the late '50s, early '60s.

34:40

DP: Yeah, into the '70s, maybe early '80s. That's probably when the company finally failed, because I left there in like 1971 or '72 to got to work for a construction company. And then I found the job with the Fire Department and decided I wanted to do that.

MK: What year was--?

DP: Oh, I started with the Fire Department in 1973.

MK: Three. Hmm. What were some of the other industries in town at that time?

DP: Oh, there was Concord Woodworking. They made. Well, they called it snow fence. It was a very simple fence that would roll up. And you could roll it out. And what it did is it created a, like an air dam. And it caused the snow to drift in another place, rather than on the road. You could-. If you knew how to do it, you could set it up so it would keep the snow from drifting across the road. And they still do it today, but they use plastic fencing. Another--. A number of other products I'm not familiar with, but then there was Slider Units, which made sliding doors and regular commercial and residential doors and windows. And I think they sold out to Home Depot at some point. Because they had a plant on Beharrell Street. They moved up to Conant Street, and is now a large apartment building there. Their building was torn down and somebody built an apartment building. But there were a lot of small companies too in town that made any number of things.

I've heard a lot of stories about different individuals that developed small products and made them on their own. They were never mass-produced in any great quantity, but. There was a lot of light industry in town. Trying to think of what else we had. Oh, there was General Radio. They developed, I think it was called a Variac. It had to do something with controlling voltage. That was a small company that I'm not sure if they're in business anymore. That's now SolidWorks, which does a lot of computer drawing programs. If--. Let's see. Yeah, I guess there's no other way to put it. It's a computer drawing program, but it does three-dimensional drawings and so forth that a lot of companies use. They can develop a product using this software. And they can see potential problems before they actually build it.

MK: Do they call that CAD, Computer Aided Drawing?

DP: Yes. Yes.

MK: Umm hmm. Hmm. So you, in '73 the, and opening came at the Fire Department? Had you had your eye, or were you fascinated with fire engines as you were with all kinds of other machines?

38:10

DP: Not r--. Yeah, I did. Anything that was mechanical fascinated me. But what I did is I worked for my father for a while after I left the construction business. I worked for Charlie Comeau. They're local contractors.

CK: Charlie who?

DP: Charlie Comeau.

CK: Spelled?

DP: C-O-M--. C-A-M-O-E, I believe. I'm a terrible speller. But.

CK: We are too.

DP: Anyway. I worked for him for a number of years, and then I worked for my dad. And he kind of went into semi-retirement. He had a place up in St. Johnsbury, Vermont. And mid-week he'd say, "I've had enough. I'm going to Vermont." So I started working at Elm Brook Farm to supplement my income.

CK: What was that?

DP: That was the stables, which I had a connection to anyways, because I liked horses. So this gave me an opportunity to ride more, and--. Plus, John Roddy was a dear friend of mine. His dad ran the stable, so it was just a natural thing for me to do at the time. And then the--. Then I saw an add for the Fire Department position, so I followed that up, and Tommy Tombino, who was the Fire Chief at the time, gave me the job. Because me dad--. I've--. I'm retiring in June. I've got thirty-eight years with the Department. My dad had somewhere around twenty as a call firefighter. And my grandfather has fifty-three on the call Fire Department in Concord. And he retired as a Captain on Chemical Two, they called it.

MK: Chemical Two.

39:58

DP: Yeah. What it was is a soda and acid system where to provide pressure for the hose, they had--. I don't know exactly how it worked, but it was a soda-acid system, typical to early fire extinguishers, and it caused an expansion in the tank, which would push the water out through the hose. And it was a chemical process. There was no mechanical pump to pump the water. But it was a short-lived system. Then they found the pumps seemed to work better, and then they developed the Rotary Thane pump that's used today, pretty much in every fire apparatus, because it's a very simple process and produces, can move large volumes of water.

CK: Sounds like such an ideal situation though working for your buddy's dad, working with horses all day. Hard to think about--.

DP: It was good, but it wasn't great money. And this, the Fire Department seemed a little bit more substantial. But at that time we worked tens and fourteens. So I'd work two ten-hour days, two fourteen-hour nights. And then I had three days off. But now we work twenty-fours. So I'll work Thursday-Saturday, and then I get five days off. So that was, gave me an opportunity to work at the stables, or work for a construction company, or I had my own small business for a while doing construction, doing general repairs, and additions, and build garages, and--. My nephew worked for me and he decided he wanted to do bigger things, so I said, "Fine. I'll work for you. So you have the headaches. You worry about things at night."

MK: I'll go home at quitting time.

41:49

DP: Yup. Exactly. Because typically I'd be at work, and there'd be a bad storm, and I'm trying to put a roof on a house, and is the tarp still there? Did it blow off? Or--? But there was a lot of neat things in Concord. Used to be the Powder Mills up in West Concord on the Maynard line, Maynard-Acton line.

CK: The what?

DP: Powder Mills? They used to produce powder for the military. After World War Two it closed.

MK: Gunpowder.

DP: Yeah. I mean they may have produced other things, other than gunpowder, like--. I mean there's some high explosives today that were used in World War Two. They were much more stable and more powerful than the powder, gunpowder was. But I don't ever--. I don't really remember--. I know some of the buildings are still there, but I don't remember the process or seeing any of it operate. But my dad did. And. Oh, let's see.

MK: And the train--. Did--? Was there more than one train going through West Concord?

DP: Concord?

MK: West Concord?

DP: Oh, yeah. Yeah.

CK: What was that?

MK: What was the train?

DP: There was the Boston and Maine. Now it's just the commuter rail. But the Boston and Maine used to run freight trains through there all the time. And for us--. For me at night, lying in bed, and the freight train would be going through. And I had it figured it that it I counted every clickety-clack, and then divided by two, that is was, you know, a hundred car freight train. Or two hundred clickety-clacks, then it was a hundred car freight train. Because there was a crossing there where the Boston and Maine crossed. They used to call it Concord Junction. And that's where the Boston and Maine crossed the--. I think it was called the New York, Hartford and New Haven Railroad. And of course they used to run freight trains through town.

MK: Is that track still visible, that cross?

DP: Yes. Yeah.

MK: I saw it this morning I think. I was walking through.

DP: Probably did. Yeah. Yup.

MK: I thought, "Wow. This was where--."

DP: Through West Concord? Yeah.

MK: Yeah. Yeah.

DP: Yeah, you would see that; the old right of way is still there.

MK: Huh.

DP: And then there was another railroad. And I think it was called the Fitchburg Line. Used to run up by the prison, over where the, Route 2, where the State Police Barracks is, there used to be a, what they call an engine house and turntable there. And it was like a--. They could bring a locomotive in, stop it. And it was like on a bridge pivoted in the middle. And they would turn the train around so it would face out the other way. And they had a big curved engine house. And they'd back the engines in for repairs or whatever.

MK: Big r--. What'd they call it? A Roundhouse?

DP: Yeah, roundhouse and turntable. There's nothing left of that. It's where the State Police Barracks is now. And then the state has a big building there. It's like archival stuff.

MK: Hmm.

DP: There's a lot of stuff that's stored there, and I'm not sure what it is exactly, but. Yeah, one point there the prison, the prison farm used to produce most of the food products for the prison and the Commonwealth. They used to have huge fields of--. Because we used to go out and steal the cucumbers. On a hot summer day it was great to--. You know, you'd go in and grab a cucumber, and it was a great little snack. Plus they had a big working dairy there that produced milk and stuff for the prison system.

MK: Well getting back to the Fire Department—

DP: Umm hmm.

MK: It sounds like it might've been kind of like a family affair. There's your grandfather with, what did you say, fifty-one year--?

DP: Fifty-three years. Well he lived on Walden Street. At one point, supposedly, he lived in the Tavern with his mother. But I found some information that says he lived with the Bartlett family on Walden Street. So he was close to the Fire Station, because it used to be what they call Independence Court. And the Fire Station's still there. It's now an office or retail space. And the engine that was in there was called the Independence. And they built a new station on Walden Street, which was used up until the late '50s. And then they built a new station further down Walden Street which we're in today. And we still have the original sign that was over the first--. Well I won't say it was the first fire station, but the fire station that's at the end of Independence Court. Now it was called the Independence. And we have a sign that was made by Rufus Hosmer in 1845, is the inscription on the back of it, because we took it down recently because they did some remodeling in the station.

MK: Rufus?

DP: Hosmer, which is an old Concord family.

MK: H-A-S-N-E-R? H-A-Z-N-E-R?

DP: Can't say.

MK: We'll have to look it up in the phone book.

DP: Yeah. I mean I'd have to write it. Hosmer. Yeah but--. So the station's still there. I--. The ownership just changed, and the guy that runs Helen's Restaurant bought it. And he's trying to find some old photographs of the station, because he wants to restore it to the point where it looked like, or as it looked, when it was a fire station. But he's not having much success to find a photograph of it.I want to say my grandfather had some old photographs of town, but I'm not quite sure where they went.

MK: So what else about your grandfather, besides being a fireman, was--? What else did he do?

47:50

DP: Well he worked—

MK: This was your father's father?

DP: --Yes. As a young man he--. I don't know the name of the company, but he used to drive a wagon, because there used to be a slaughterhouse in West Concord off of Old Stow Road, and he used to drive a wagon, and I believe it was twice a week, to Boston, loaded with meat. And suppose--. As the story goes, he was stopped in Arlington and they commandeered his team, because there was a huge fire in Boston. And they needed additional horses. So he wound up in Boston. And he worked caring for horses while the fire fighters were fighting the different fires throughout the city. And I don't know the actual date of the fire, but this is, it's how the story goes. So it's something I heard from my parents years ago, and I never pursued any of the details. And I wish now that I had.

But it was quite a town. Still is. Still is. I was--. I forget who I was talking to the other day, but we were talking about Concord and what a great place it is to live and grow up in, and--. You know, it's just got so much history. And I think--. And my dad probably felt the same way. And my grandfather probably felt the same way that there were certain things that were here when I was a child that are gone now, and it's a loss to the town. And I often think, is the town going in the right direction? Well it's the only direction the town can go in. It's going to grow to a certain point. And things are always going to change.

MK: Umm hmm.

DP: But, no my dad used to do a lot of work for Concord Academy as an electrician, do electrical repairs and stuff.

MK: Right across--?

DP: Yeah. Used to be just three or four homes. And now it's several homes. Plus now they got a couple of huge buildings out back. I mean they were never there when I was a kid. Quick story: When I--. As a fire fighter I took a promotional exam. And one of the things they did is everybody that took the promotional exam for Captain got to be Acting Captain for four weeks. Well, it was my turn. It was September. And they had a meeting, because the Town was changing, I forget what it was. They were changing something that had to do with house values. So they had a meeting at one of the local schools. Well the place was a disaster it was full of people. They had exceeded the capacity of the building. People were parked everywhere. And the Police finally called me and says, you know, "Can you do anything about this." So I went up, and I spoke with the Town Manager, and I says, "I really don't know what to do, but I mean we've exceeded the capacity of the building. We're going to have to have everybody leave and reschedule the meeting." And he agreed to that. And I guess the committee that was actually running the meeting was a little disappointed, but it was on the verge of being out of control.

51:16

But anyway, so it was a nice cool, fall day. And we get a call for an oil leak at Concord Academy. So we went down and the old gymnasium had an oil burner system that was on the roof. And some thing sorted out, and it pumped like 150 gallons of oil onto the roof the building, which dissolved all of rigid foam insulation. And it got into all the storm drains and got into the storm system at the school. And it was headed for the river before we finally got it stopped. But it was a major project for them to clean it up. And if you--. While they were doing the cleanup they changed the oil burner to a gas burner, so there wouldn't be any more issues with oil on the roof. And then a few years later they tore the building down and built a whole new building, which they have today.

MK: The Concord oil spill.

DP: Yeah. We've had a few. I've had a couple on Route 2 that were pretty massive, but we managed to--. The technology today, compared to, say thirty years ago--. Thirty years ago we'd put some chemical on it and wash it into the storm drain. Today we try and capture it all. And we have these different materials that'll absorb the oils, but not water. And the EPA comes in and they bring in Clean Harbors or whatever, and they dispose of all the contaminated material. So.

52:50

MK: So tell us about the ten most exciting fires you ever fought.

DP: Well.

MK: Would ten be enough?

DP: How about three or four? Well the last one we had was on Partridge Lane and that was pretty extensive. It was a fairly new home and the owner had cleaned out the fireplace and put the ash in a plastic pail, put it on the back porch, and, you know, with the intention, you know, I'll get back to this in a few minutes. He knew he shouldn't leave it there. But, trying to get the kids ready to leave at mid-day and all the other things that happen in a home during the day, he forgot all about it. So as they were getting ready to leave, his wife noticed that the back porch was on fire. So by the time we got there--.See typically today they use--. Some of the modern materials are PVC-based, like handrails, and balusters and posts are wrapped with this PVC-based material. And it's very durable. You don't have to worry about painting it. It doesn't support mildew. But it burns very good. So once the porch got going, where it's on a hill, the afternoon breeze came up the hill and carried it right up through the porch into the master bedroom over the garage, and by the time we got it stopped, the whole roof of the house was gone. And they tore it down.

And the sad thing is they were there on our arrival. And typically fire fighting doesn't always go as it does when you train. Not that we had any problems, but it just takes time to get the truck set up, to move hand lines around. And as we run minimal manning, because it's expensive. And it's probably three percent of the time we're fighting fires, as I was told years ago. Seventy-five percent of what we do today is EMS, you know medical emergencies. So, we were kind of shorthanded, and I had to wait for the other engine company to come, because under federal regulations, my job is to stay in the street as the incident commander. But we can't always do that. And what we would do if there was a life hazard issue, is I'm not going to worry about water, or federal regulations, life safety is our first concern. And we'd do our attempt to rescue. But we did finally get water on it. But due to the modern types of construction, and the materials used, the fire got a head start on it. I--. Actually it was Super Bowl Sunday, because we were getting ready to make jambalaya and get ready for the Super Bowl game, and we got called out.

55:50

And this house is right up behind the fire station. So as we pulled out of the station and turned right, I looked over my shoulder. I didn't see anything. So I thought, "Well, this is probably maybe steam from the dryer or something." Turned onto Hayward Street. There was a huge column of black smoke, and I said--.That's when I struck the box, meaning a box alarm. That puts out a tone that brings in all off-duty fire fighters. I got to the front of the house. I immediately went to a second alarm, because I knew we were going to need help. That brings in other towns, like Bedford, Acton, Maynard, Sudbury, Lincoln. And by the time we got the first hand line into the house I went to a third alarm. I knew we were going to need even more help. And it's kind of what they call a mutual aid pact. There's an agreement every town has. If you call us, we're going to send what we can. And the other towns do the same thing for us.

56:53

So. Let's see. I had a fire. This is probably fifteen, eighteen years ago on Old Bridge Road. Old Marlboro Road at Old Bridge Road. And on our arrival we had the ladder truck parked in the driveway, and a young lady came up behind me. As Incident Commander I'm out in the driveway. And she was hysterical and said, "They're still in the house." So. We had just gotten a crew inside with a hand line, and they'd started up the stairs to the second floor, because the majority of the fire was in the attic space and went into the house. So when she told me that they were, the occupants were still in the house, the next two engine company, their job was to go in and attempt to rescue. And I ordered the operator of the ladder truck to take some windows out on the second and third floor, and I used to ladder to poke the windows out. And that gives the heat and smoke some place to go. So it makes it easier for us to come in underneath the fire. As all this heat and material's moving up through the building, it's easier for us to get through the building.

58:06

Come to find out they were away. They weren't in the house. But the Lieutenant, after we got the fire knocked down come out. Looks up at the ladder, looks at me. He says, "That little ladder look bent to you, Captain?" Which means, he was concerned that we may have bent the ladder. But we never did. He was trying to give me something else to think about. It's typical of fire fighters to give each other a hard time. He was just--. He was--. Because I took a step back, and I had to look and go, "Oh. I think it's all right." But which would've been a big expense, but if we had saved a life, it would be well worth it.

MK: But there was no body in the house.

DP: No one in the house.

CK: That sounds incredibly difficult to figure out where to start in a full size, smoke-ridden house.

DP: Yeah. Well typically, you know, we--. If the house--. Well we had a fire here at Fritz & Gigi's. And why I bring that up is it was textbook. Everything went like clockwork. And we got a report of an order of smoke, because the front of that building is retail. The back is, there's a couple of apartments. And the woman in the apartment called and says, "I smell smoke." So my thought was, well, it's probably from someone fireplace or chimney. So we pulled up and didn't really see much. And I questioned her. And she says, "Yeah. I've been smelling smoke for hours and I'm smelling more and more now." Well, this is probably early in the morning, so it's dark. Well I took a good look, and I got a flood light on the house. And I could see smoke coming out of a gable end vents. So we called for a box alarm. I had the ladder truck ladder the room and cut a hole in the roof. And right in the middle of the building they cut out a four-by-four section of roof. And just as they did that, the second two engine company, I had them already inside with a charged hand line. And when they opened the roof, the fire came right out through the roof. Well they were there at the perfect time, the second engine company. And they opened up a hand line and they knocked the fire down in five or ten minutes.

CK: A hand line?

1:00:25

DP: Yeah. It's a small diameter hose that we move by hand, so we call it a hand line. And it's typically what we use first. You know, house on--.

MK: About a four-inch hose?

DP: No, no, no. It's inch and three quarter.

MK: Inch and three quarter.

DP: Four inch hose, once it's charged, you're not going to move it—

MK: Ah.

DP: --because of the sheer volume of weight. Plus it gets very, very stiff. And it's almost impossible to move. So we use what they call an inch and three quarter hand line. When I first started we used a booster line, which is like a heavy duty garden hose. But that was state of the art then. And with training and FPA [Fire Program Analysis System] doing different experiments, they found that using an inch and half or inch and three quarter hand line is, you can put down more fire quicker.

CK: Sounds like a garden hose.

DP: Yeah.

MK: Well.

DP: It's like one inch--. It's called a one-inch high pressure--. Oh, we don't use them anymore, so I've forgotten. But it's what they call a one-inch booster line. And it's high pressure. But it's minimal volume, where the hand lines we use today are inch and three quarter with a combination nozzle, so we can either use a straight stream or a fog pattern. And we use what they call the indirect approach. So we typically--. We'll come into a room, and there's a fire involved in the room. We're low. Turn the nozzle up, open it up for thirty seconds, shut it off. And that pretty much puts the fire out. Then you open up the windows, and you go around and put out the hotspots, so you can put out a great deal of fire with very little water, if you have the right personnel and use the right technique.

MK: There's a lot to know about this.

1:02:21

DP: There is. There is. I mean it was pretty simple when I started, but after you went through the Fire Academy, and as the technology changes, it becomes very much involved. And it's much more scientific now than it ever has been.

MK: And you've had to update your own training through your career?

DP: We train. Every day is a training day in the Concord Fire Department, the Chief likes to say. So everything we do is based around training. If we--. Because typically every morning we go through the engine, and the ambulance, and the ladder truck. We check all the equipment, make sure everything's' there, everything functions. If it doesn't, it's tagged and put out of service, so that it can be repaired. And then weekly we do a--. We pretty much take everything off the truck, clean it, check it, make sure it works properly, and then it goes back into the truck. And every year we pull all the hose all, and test all the hose. We bring it up to a certain pressure and it has to stay there for a prescribed length of time. And then you can check the hose to see if there's any weepage, or any leaks, or the couplings don't look good or don't work correctly. And then that hose is taken out of service, to be repaired or replaced.

CK: So you're there so many hours. Sometimes you're checking equipment and sometimes you're making jambalaya, I guess.

DP: Yup.

CK: How does that all get determined?

DP: Well, see it's just what the group does. It's a group atmosphere. And we rely and depend on each other, and even right down to the menu. We discuss it at some point during the day, "What's for dinner tonight?" Because now we work twenty-four hour shifts. And typically lunch is something that you eat, you bring with you. But we all--. All of us keep some food stuffs in our lockers, some cereals and stuff in case you get held over. But as groups we each have a food locker, which we keep condiments in, some sugar, salt, pepper, dried foods and soups and--. But what we typically do is go out during the course of the day, put together a menu. And if we go out on a run,, on the way back we'll stop at Crosby's and pick up what's ever on sale for dinner that night. So.

CK: Who gets to be cook?

1:04:47

DP: Oh, there's one or two guys that like to do it. I typically don't cook, because I, I've got paperwork to do and I have all I can do to boil water. I'd rather take the stove apart and fix it than cook on it.

CK: Well you have all this paperwork. What's your position?

DP: I'm a Captain. And I keep a record of everybody that's on duty. If somebody's off for vacation I keep a record of that, an ongoing record each month as to how many sick days or personal days of vacation they've used. Because you accumulate like so many sick days a year. Each July 1st you get--. It depends on how many years you've been with the Department. You get anywhere from two to five weeks of vacation. So I record all of that. And if you carried over any from the previous year, so I have to keep a record of each guy and what he has for time on, time off. If anybody's working overtime I do a payroll for that day, which goes upstairs to be reviewed by the Chief. And then he'll sign it, and it'll go to Town Hall for payment. So.

MK: A lot to keep track of.

1:06:05

DP: Yeah. Yeah. And then anything that goes wrong with any of the apparatus I have to keep a record of that and make sure that the maintenance people are aware of it, and--. What I do is like when I get relieved in the morning I'll sit down with the Captains coming on duty and discuss different things we did and problems we had and it there's anything missing. Excuse me. —on the truck, or the engine, we'll make him aware of it. Plus we record it. We have like a bulletin board, and every vehicle's listed. And I'll say the vehicle's "in service," "out of service," what equipment's been taken off for whatever reason.

MK: Well in your own case it was--. It turned out to be a family affair, possibly, that brought you into the Department.

DP: Yeah. I don't say I went looking for the job, but I did take it, and it became a career.

MK: What about the other personnel? Is--? Are there other people who had grandfathers who were involved, or--?

DP: Not typically on the Concord Fire Department. There aren't many people that live in town anymore that are involved with it. When I started, I mean everybody that was on the Department lived in town. The Call Department was made up of townspeople. And if we had a fire that'd be the eight guys on duty, plus a number of off-duty fire fighters, plus the Call Department, and Civil Defense would show up. And they were like support for the regular fire fighters. But that's all gone today. Nobody wants to do it. You know?

CK: How come nobody lives in town?

1:07:50

DP: It's too expensive to live here. We had a guy from Florida that looked, was selected for the Fire Chief job. Or he was like in the top two. And he came up and looked at real estate here, and he said, "I can't afford to move up here." So he refused the job. That's the only reason I'm on the Fire Department is I grew up here and I happened to buy a house, you know a little house years ago, and I'm still there. But new fire fighters can't afford to move into town. Same with the Police Department. There are very few Police Officers that live in town.

MK: Huh.

DP: And it's too bad, but it's the way the town's gone. It's--. Real estate here is very expensive. My house, I paid $25,000 for it, and it's worth a half a million dollars now. And it's just--. It's incredible. Houses that--. Well I used to see a lot of the estates, because I worked over here where Chang An's Restaurant is. Used to be Worthmore Feed and Grain. And I used to deliver feed and hay and stuff like that to different people at some of the estates. And they had horses or whatever. So that was interesting. I got to see some really beautiful places. But now those places are pretty much gone. They've been cut up and sub-divided and--,

CK: So you feel like there are more sort of different echelons of wealth—

DP: Oh yeah.

CK: --than there used to be. Can you talk about that?

DP: Yeah. There were a number of wealthy people in town, but it was more of a working class town. But there were wealthy people. There was Henry Lockland, who had an estate up on Monument Street where I used to deliver feed and grain. And he just had a great big place. And there were a number of wealthy people, but there were still a lot of working class people here. A lot of people from Nova Scotia used to come down this way.

MK: Huh.

1:10:01

DP: At one point, I think I was probably related to half of the town employees. They were related to my family in some way. But that's all changed. I-.There are very few town employees, say in Public Works, that live in town. Or the Light Plant, for that matter.

MK: Does that produce a worker with a different level of commitment, do you think, if they live somewhere else?

DP: I think it can, but what I see in say the Fire Department, and I can only probably speak to that, is that the people that the Town has hired in the past twenty to twenty-five years are dedicated to their profession. Doesn't matter. And Concord seems to be a popular Department, compared to surrounding towns, because we have a lot of members on our Department that have come from Acton, or Lincoln, because it's a busier Department. We've got a lot of responsibilities. We have the Emerson Hospital, which is a target for us, because, I mean even though it's a well-maintained and cared for building, there's still a potential for a problem. And we have two prisons. We have the Northeast Correctional Center, plus MCI Concord. We have large nursing homes. And now Lincoln has a new nursing home right on the Concord Town line on Route 2, and we go out there quite often, because Lincoln is a small department. They can't keep up with their growing demands. And I think Lincoln's department will grow over the next few years. As I say we have the nursing homes. They're our meat and potatoes, so to speak. I mean we go there quite a bit. And a lot of people, I mean probably ten percent of the calls that we get are calls that they probably don't really need an ambulance, but they don't know what to do. We've seen people with similar to a paper cut, but they want an ambulance, and they want to go to the hospital.

MK: Have any women ever applied to—

DP: We had--.

MK: --to be firefighters?

1:12:15

DP: Yeah. We had a woman, a girl in the Fire Department. And she was there for about twenty years. And then she got married and had a couple of kids, so the family became the--. She had to leave the Department so she could care for her family better and spend time with the kids. Same with the Police Department. They've had a number of female police officers. They come and go, and as they transition to some of those smaller departments, we've had people come on our Department that want to be fire fighters, but they want to get on a city department, like Boston, whatever. So you start out in Concord. And then you wind up in Quincy, or maybe Brookline, or Belmont. And then you wind up in Boston or Cambridge, which are what a lot of guys like to do. See Concord is not Civil Service, where most larger cities and towns are. And guys'll take the city Civil Service exam, and they get on a list. But it takes time to get into a city department, because it is a popular position. A lot of people like--. I won't say a lot, but there are a number of people that are--. And I--. It amazes me how many people want to be a fire fighter or a police officer. You know I wouldn't want to do that. I wouldn't want to be a police officer. I don't think I could do it.

MK: What about the spouses of fire fighters? Is there an auxiliary? Is there a--?

DP: There was years ago.

MK: Is there any social involvement from spouses?

DP: Well there was years ago.

CK: . . . .

DP: Excuse me?

CK: Do they come over for jambalaya?

1:13:56

DP: No. No, they typically don't come near the station. But like I say, they don't live in town. They're in Ayer, or Fitchburg, or Quincy, or Chelsea, or Boxboro, Bolton. There was a Lady's Auxiliary, years ago. And it was more of a social fiber to the Department then. I mean everybody that was on the Department lived in town. They socialized in town. They used to have the Fireman's Ball, which was a pretty big deal. But all of that has changed. As people move out of town, they're--.What would you call it? They just don't have the interest in the town that the people--. You know, when they lived in the community it was a social event.

MK: Huh. Well this has been great. I'm wondering what else we should ask you, or what you feel like you haven't talked about yet.

1:15:00

DP: Oh, I don't know. I'm sure I'll think of a lot of things tonight.

MK: Umm hmm.

DP: But I'm trying to talk about different things throughout town that I experienced as a young man growing up. And I caddied at Concord Country Club, and that was an experience.

CK: Why?

DP: Oh, it's just different people that were involved with the Club that, and how they reacted to the caddies. It was different. I just--. I saw--. There's one side of people that I had never experienced before, like, not to demean anybody, but doctors and lawyers were typically poor tippers. But the regular guy would give you a good tip. You learned that there were certain people you didn't want to caddy for. You'd see him coming into the Club, and you'd go around the back side, so you weren't available! You'd wait for the guy that would give you more than twenty-five cents. He'd give you a couple of bucks, you know. But, twenty-five cents actually, back in the '50s wasn't bad money, because you could buy a whole lot with a quarter.

MK: Umm hmm.

DP: Can't today. Popsicles used to be a nickel. I don't think you could find a popsicle in town today.

MK: No. If you could, it'd be more than a buck.

DP: Oh yeah. Yeah. No, it's where we used to go to the Colonial stores over here. They had--. Not Colonial, but the country store. And they had a whole section of penny candy. But I think just before they closed, going in and looking at the candy was much more than a penny. But.

MK: Umm hmm.

1:16:55

DP: And I think the store that's in there now agreed to keep a little section of what they call penny candy. But it's still candy, and it's not a penny, but.

CK: Did they have old drug stores where you could get, like a soda fountain?

DP: Oh yeah. Yeah. I mean there were two drug--. Oh here's an interesting story. It's in a book here in the library. It's a chronicle by Lawrence Richardson of the Concord papers from 1865-1900. I've forgotten the exact date, but it's like 1890 it says, "A young reveler threw a firecracker under an ice wagon, which stampeded the horse, which ran through the center of town and took out the two corner windows at Snow's Pharmacy." And it goes on to say, "Robert Merrill Prentice will appear before Judge Keyes in the following week," which was my grandfather, because he lived on Walden Street, and he must've just thrown the firecracker, and it spooked the horse, and--. But then there was a story about a horse, or a team of horses that got away, and my grandfather, supposedly stopped them by going out to them. And as the team came by, he jumped on the horse and reigned them in, so that the--. So, I--. I've only heard it through family members, but nobody else has ever mentioned it, other townspeople that may have seen it or heard the story. So I can't--. I don't have any facts, but, other than what I was told.

1:18:35

Another thing: There was another section in there about a gang of Italians moved to town. And I always bring this up to Doug Macone, because I grew up with him and he's my dearest friend. And it said, "Gang of I--." Headlines read, "Gang of Italians move to Concord." Then it goes, "The Macone family will be working for the Wheeler farm, or--." But--.

CK: The Macones were Italian?

DP: Yeah. Yeah. And they were quite a family. They had--. They're a very hard working people. And Ralph Macone, who they call Peanut, because he wasn't much more than five feet tall, used to run a little hobby shop on Walden Street. And they he moved down the Lowell Road. He had a bike shop, and he, sporting goods, and fishing, and hunting, and--. He had all that stuff. And he was a real character. And he was on the Independent Battery when I started.

END OF FIRST TRACK 1:19:39

TRACK TWO

DP: Actually, he kind of, I guess he was instrumental in getting the Battery started again after World War Two, because the guns were placed in the basement of 51 Walden, which at the time was the Veteran's Building. And they used to keep the cannons in the basement. And they were placed in there and kept there during the war years. And he played an important role in getting them back out and getting the gun crews together and all the equipment necessary to keep them going, because if you look at the guns, there's an inscription hand-tooled into the top of the guns about the battle at April 19th.

MK: And they were made--? They were caste where?

DP: Watervillette, New York.

CK: What's that now?

DP: The guns were cast in Watervillette, New York. And it's a big armory, and they made guns. And this is where they were manufactured. And I don't know where the state got them, but the Battery wound up with them. And they had a local gunsmith. He hand-tooled in it an inscription of the battle. If you get a chance, you might go down, because you can look in the windows and see the guns. They used to have it you could push a button and it would bring on lights. You know, it would light up the guns, and. Because the Battery and Friends of the Battery built the gun house in 1960, where they used to stored in the bottom of the Veteran's Building. So they felt this was more suited for their care and maintenance, rather than sit on a damp floor in the basement of the, you know an old building that was very rarely every used. But now it's 51 Walden, which is--. They do a number of plays, and they have band concerts, and--.

CK: So, we did some interviews with Rod & Gun Club members, and so Concord has this history with this weaponry.

DP: Oh yeah. Yeah.

2:03

CK: I mean how does that relate to say, views of, that relate to the NRA, or gun holding in a more general way?

DP: I always grew up with the thought that here's where the Revolution started, so basically the things that we, I mean some of us take for advantage--. I don't know where I want to go with this. It's--. You know it all started here. It was a call to arms that forced the British out of town and started the Revolution. So there's always been that history of guns. Growing up there was the Rod & Gun Club, the Musketaquid Club. There was always shooting. There'd be skeet shooting, and trap shooting, and--. Today it's more into using specialized bows and arrows, but--. Because the neighborhoods have encroached on the gun clubs, so they're trying to stay away from the use of guns, because of the noise and the potential. You know, an arrow doesn't travel quite as far; and it doesn't make a lot of noise. Yeah, but growing up there was always gun clubs, and it's like the Musketaquid Club, every time a member of my family got married, that's where they'd have the reception. And it wasn't because of the guns, but it was just, they were members of the club. Um—[Sighs deeply]

MK: So a strong belief in the Second Amendment.

3:47

DP: Oh, yeah. Absolutely. I think so.

CK: What was that?

DP: A strong belief in the Second Amendment. But I mean there's been times when the Battery was, people didn't want to Battery to fire, you know the Concord Artillery. Because they just don't believe in guns. But that's their prerogative. You know everybody has rights to believe in what they want. I don't own a gun. I'm licensed to carry large capacity weapons, but I don't own a gun.

CK: You don't?

DP: No. Just never had any desire.

MK: Not a gun guy.

DP: No. Not really. I mean they interest me as, in a mechanical way. I used to hunt. But I never really owned a gun. My dad had a shotgun, which I used as a young man to go hunting. But I just never had a desire to go out and buy a gun. So. But I am licensed. I think my wife deals in guns more than I do. She works for an auction company, and there's always estates, and you know there's a closet full of guns and whatever.

MK: She works for a--?

DP: Skinner, Boston. It's an auction house.

MK: Oh.

DP: Supposedly one of the larger, you know like Sothebys and all. And Skinner's up there somewhere. They deal in fine arts and antiques.

MK: Did you raise any kids up to be firemen?

DP: No. No children.

MK: No children.

DP: My brother's a landscape architect. My sister is a housewife and lives in Biddeford, Maine, but. My brother was always out in the woods, and--. And he has a green thumb like my grandmother had. He could make anything grow. And I always wanted to cut it down with a lawnmower! My wife's the same way. She loves to garden. But to me, gardening is, well we got to get a rodotiller and get metal fencing and stakes. But she's, "No, let's turn it over with a pitchfork." "But that's work." So yeah, I think a lot about Concord. And I think a lot of it. And I've spent a lot of years here, and I hope to spend the rest of my life here. . . . Funny story: I can remember being a child with my grandfather and someone asking him if he had lived all his life in Concord. He hesitated for moment, said, "Not yet."

MK: That's the answer, isn't it.

CK: Yeah, it--. I mean it sounds like a real brotherhood at the Fire Department.

DP: Oh, it is. Absolutely. Yeah.

CK: What's that?

DP: I mean we depend on each other. You go into a burning building, and you got to know that guy's behind you. Or the guy that's in front of you, you got to stay with him. And we have the--. It's basically like skin divers. It's a buddy system. If you go in with somebody, you come out with somebody.

CK: How can you ever leave there?

DP: Leave what?

CK: The Department.

6:37

DP: Oh. I don't have any choice. You know, it's sixty-five, and we're all done. Doesn't matter if you're healthy or not. So. But anyways.

MK: Plans?

DP: I'll do some light construction. And I have, like carpentry. And I have a knack for old cars, and I know a number of people around that have old cars. So I'll do some minor repairs and maintenance for them. So I'll keep busy.

MK: Hmm.

DP: I bought my own--. I bought an old truck years ago. Actually I've had it for pretty much all my adult life. And I fixed it up over the years. But it wasn't, didn't quite cruise down the road like it should, so I put a Corvette engine in it. And I do all the work myself, so, which is fun. Now that I've got it all done, I hardly ever drive it, so. I think working on it is more what I like to do.

CK: We've interviewed people who just seem to have this incredible sense of volunteerism. They join every committee, and—

DP: Umm.

CK: --go to so many meetings, and I just—

DP: Well my wife did.

CK: --wonder how absorbed you'll get.

DP: Yeah. My wife, she was on a number of committees for several years. But her position with Skinners grew and it got to the point where she really couldn't do both. It was either one or the other. But she was on the Planning Board and the--. Oh, she started out on the White Pond Advisory Committee, which is a group of residents around White Pond. As the Pond is developed, this committee has the ability to talk to you and to make sure that you're not going to do anything that is going to, well not injure, but kind of mess up the pond. Because it is a kettle pond. There's no water in, no water out, other than rainwater and groundwater. And all these little cottages have been made into year 'round residence and have grown, and expanded, and modernized. It does have a adverse affect on the pond, because it causes--.

MK: Lawn fertilizers and--?

DP: Right. And just the rain runoff from the roof, it causes--.What do they call?—Oh, I can't think of it. But it has to do with--. It causes eutrification of the pond, and it promotes weed growth, and algae blooms, and--. It's phosphate loading. Just the rainwater off the roof, if it isn't trapped in the ground, runs off into the pond. It increases the phosphate loading. I don't know just exactly how it works, but that's the way it was explained to me. So they kind of keep an eye on the pond and what's going on around it. And they make a recommendation to the town, let's say if you apply for a building permit because you want to remodel. So--. And it's all residents from around the Pond. And she started out there, and then went into Public Works, and the Planning Board. And she did a study on West Concord, because there's issues there that are growing, like Commonwealth Avenue and the amount of traffic, and the old railroad right-of-way. Where the actual crossing is now, it's like a small park. And my brother designed it. And he took the crossing, which is the, where the two railroads cross, and that's kind of the center point of the park.

MK: Um.

10:23

DP: But that could change. I know they're talking about a bike path and using the old railroad right-of-way. There used to be a bridge out back that crossed the Assabet River, but they took that out a number of years ago, because two kids fell off it.

MK: Wow.

DP: Drowned. So they figured the best thing to do is to take the bridge out. But that could've been probably used to expand the bike path. It hasn't been done yet, but I know there's still talk about it. And. We used to have a great time on the river. There was a lot to do around Concord. You know I mean kids today typically sit in front of a computer and play computer games, or--. I mean when I was a kid the only computer in town was on Baker Avenue, and it took up an entire building. And you had to be a genius to operate it. I know when they took it, when they shut it down, the Smithsonian Institute took it.

MK: Oh.

DP: Because it was one of two or three. And I guess it had a lot to do with the early space program. Because there weren't that many computers around. And they say today, a typical wrist watch has more computing power than that entire building had. It's amazing.

MK: Well this has been a wonderful interview and a lot of insight about all kinds of little details. I love your--.I love your love of horses. And I bet you'd have been a good fireman back in the days when they had horse-powered—

DP: I bet I would've enjoyed that.

MK: --fire fighting machines.

DP: Yeah. Yeah. The guys at work say--.I've been around since the horse, but--. I just--. I spent a week out in Arizona with some of my friends that grew up in Concord. And we go out to the Orme School and do a five day ride out through the Verde Wilderness, and camp out. It's just beautiful country. Absolutely beautiful. And it's a great way to see it, on horseback.

MK: Yeah.

DP: Ah.

MK: Well thank you for coming over today.

DP: You're welcome.

MK: I appreciate you very much.

DP: I apologize for being late.

MK; Not at all.

CK: Thank you so much.

DP: You're welcome.

END OF SECOND TRACK.

Back to the Oral History Program Collection page

Back to Finding Aids page

Back to Special Collections page

Home