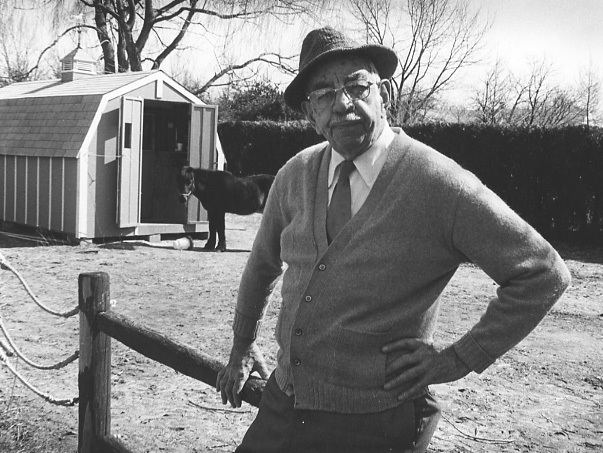

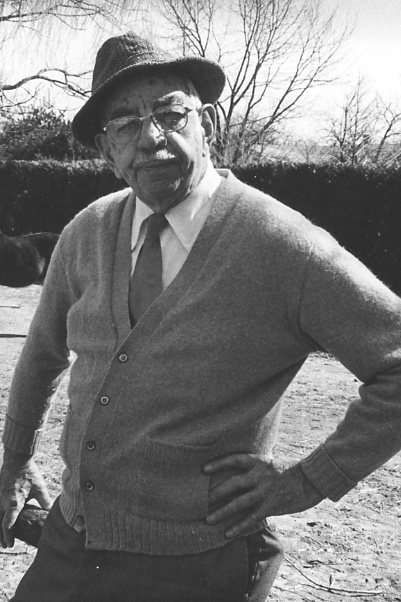

James W. Powers

524 Harrington Avenue

Age 73

Interviewed November 18, 1980

Concord Oral History Program

Renee Garrelick, Interviewer.

Jim Powers gives an excellent feeling of neighborhood and captures the atmosphere of community spirit. Growing up behind the depot had great meaning for him.

Jim Powers gives an excellent feeling of neighborhood and captures the atmosphere of community spirit. Growing up behind the depot had great meaning for him.

The neighborhood,"behind the depot"

-- Boyhood activities

-- Individuals and occupations of the depot area

-- Colorful figures of the Milldam remembered

-- Irish Wakes

-- Kitchen Rackets

-- The Minstrel Shows

-- Reading of a poem dedicated to the "Old Depot Crowd"

-- Playing the old accordion

I grew up in what we called "back of the depot" on Grant Street. "Back of the depot" at that time consisted of Belknap Street (we always called it High Street), Grant Street, Brooks Street, Elsinore Street, Byron Street, and a little piece of Sudbury Road. There were primarily Irish, a large group of Italians, and quite a few Norwegians and Swedes living there. They all mixed together and it was a nice big, happy family back there. They all had various functions, the Irish had their "kitchen rackets" which were nothing more than Saturday night dances in somebody's house, and the Italians had their big christenings on a Sunday afternoon and everybody went to those.

When it was decided whose house they were going to hold the "kitchen racket" in this week, everybody from the area would congregate at that house on Saturday night. The first thing they would do is pick up the kitchen stove and take it outdoors. We didn't have furnaces in those days, they were all stoves and fireplaces but mostly stoves.

They took the stove outdoors to get it out of the way because they danced in the kitchen. Downstairs they would have a keg of beer, and all the women that went dancing would be sitting in the living room and dining room, and the men would be in the kitchen. There would be wine available for the women. I never saw liquor abused at anything back there at all. The music was supplied by people playing accordions and violins. They danced what we called square dancing, they were jigs and reels and eight-hands around. It was a great lively time. Quite often with the rhythm of the music and the action, there would be a question whether the floor in the kitchen was going to hold up. They would go down to the cellar and get a pole and stick it under the floor. As a matter of fact, the house I lived in on Grant Street, I remember them doing it to the kitchen floor there, putting a post under it, and bet it's still there.

As far as the wakes go, when a person died then it was a great concern to everybody in the neighborhood. They were all disturbed and upset about it. All the women would be bringing over cakes and things because the whole neighborhood went to the wakes. And they stayed there. People made it a point that the body was never left unattended. There was somebody there all the time so the folks were kept busy to try to make it easier.

It was a very solemn affair. The body would be in the living room, most of the women would be in the living room and dining room, and the men would be out in the kitchen. Quite often there would be a bottle of whiskey in the pantry and they would go in and help themselves to a little shot of it. Stories would be told out in the kitchen and laughter in the kitchen. No disrespect, in fact, just the opposite. It was a real family affair and death was accepted as something that had to be, but the deceased and the family were never left alone for a minute until the funeral was over. All the nationalities were in it together and had great concern for each other.

The kids today are at a disadvantage in my opinion because the town has grown up so much they don't have what we had. We used to play baseball in what we called the cattle show field, which was a big acreage up at the end of Belknap and Elsinore Streets. It had once been the cattle show grounds and the circuses used to come there, even Barnum & Bailey. I can remember the circus trains being put on sidings there down by Wilson Lumber, and all the elephants, early in the morning, being marched up Belknap Street to the cattle show grounds where the tents were pitched.

It was a very active place up there and prior to that there was a half mile racetrack up there. I remember one race on that racetrack, sulky racing, only one so it must have been the last race there. And prior to my time, there was a big building on there called Agricultural Hall. I never saw it, but there was a big granite cellar hole all my childhood and that was a great play place for us kids.

We used to play scrub, that's a baseball game. The kids today wouldn't know what scrub is. We just called it scrub 1, scrub 2, and scrub 3 and so forth; and no. 1 would be the batter, no. 2 would be the pitcher, and no. 3 was the catcher and so forth. We would play run-sheep-run and steal-the-eggs; but the kids today would get run over if they tried doing that on the streets today.

I never swam in my life strangely enough and yet I grew up in a canoe. There were swimming holes right at the cattle show grounds in the river there. A lot of us fellows in those days used to pick up spare money by trapping. Muskrats, skunks, mink, and raccoons were plentiful, and trapping was quite a big business among the young fellows. That's where we got our pocket money. Their folks didn't give it to them because they didn't have it to give. In those days, we'd get $2.50 for a muskrat skin, the same for a skunk, and $18 for a mink so we spent a lot of time in the river trapping and fishing. Really I grew up in a canoe, I never swam in my life, isn't that strange? I tipped over a number of times and I just grabbed the canoe.

Everybody raised chickens and quite a few raised pigs for family use. That was a chore I didn't like, to get sent out to chop the head off a rooster to have for Sunday dinner. It wasn't one of the pleasant memories, I tell you, but we had to do it because it was a source of food.

Nobody was badly off but nobody had any money either. We never thought of ourselves being poor and yet we had no money. My father had a bicycle, a New Englander, and our neighbor, Bob Woodlock, had a Columbia that they rode to work. They both thought they had the best bike, of course.

On Cottage Lane there was an area with a small group of houses that was always called "the patch". Along one of the railroad sidings, there was some holding pens for cattle, and I can remember cattle being driven down from Nine Acre Corner, up Grant Street, across the tracks over to the holding pens on Cottage Lane. There usually would be one or two cattle cars standing on the siding and they would load the cattle into the cattle cars.

At the railroad crossings, there was what you called shanties, little buildings about five foot square, and there would be a man in that around the clock, eight hour shifts, three shifts a day. My father was a crossing tender in his later years. They manually operated the gates. In between trains there were three or four men in there, squeezed in believe me, around a little bit of a table playing a card game. Many times I had to pitch hit for my father, and I would tend crossing as a young fellow. They were called gate tenders. They picked up the mail from the train too.

The trains would fly through there, one of them was Concord's pride and joy called "The Minuteman". It was called that because it's schedule called for a mile a minute. It came through Concord every afternoon, late in the afternoon. As it went through the town, the man on the baggage car would have the door open and the mailbag for Concord sitting on the edge of the door, and just as he got by the crossing, he would kick that bag out and it would go flying across the field. And then he immediately pulled a steel arm up that stuck out from the car and up ahead of him would be a mailbag that was tied in the middle, and this arm on the car would snag that bag off its moorings there and off it went at a mile a minute.

Down on Grant Street, there was a blacksmith shop owned by Tom McGann. I believe his son, Joe, is still living out in California. They shod horses there. It was a picture postcard sort of a blacksmith's shop. It was swayed back it was so old, and it was partially caved in and out on one side was a big mound of discarded horseshoes. Down the street on Sudbury Road was another blacksmith's shop owned by Johnny Moreau and his father. And that was as neat as a pin. That was just at the entrance of where Stop and Shop is now. Out in front there was a great big granite, circular rock on which they put the iron tires on the wheels. It was quite an operation.

Speaking of horseshoes, it was one of the sports of the older men particularly. They would play every evening, two men to a team. They played from early spring until late fall. In the fall when it got dark and they couldn't see so well, they would light bonfires behind the stakes so they could see what they were pitching at. They took it quite seriously. They were real horseshoes, they weren't bought shoes.

And speaking of the racetrack, one of the things that comes back to me is the mud turtles, great big snapping mud turtles that must have weighed 40 lbs. They would come up from the river each spring, and they would dig into the elevated side of the racetrack and go in there, lay their eggs, cover the hole up again, and off they would go back to the river. The sun and the heat of the ground would hatch those eggs. I must say many times we dug the eggs out and we were amazed at them. They were sort of rubbery, tough-like; they didn't have a brittle shell like a hen's egg.

The hurdy-gurdy man used to come around. He had a horsedrawn little vehicle with a hurdy-gurdy that looked like an organ with a crank on it. He would stand and crank away and the music would come out, and the womenfolk would be out on their piazzas listening to him. Sometimes he had a little monkey with him, and they would give him a little bit of money. It was a nice thing to remember.

The ladder man--I always felt he came from Waltham. He had a pair of horses on a wagon almost like a firetruck. As soon as he showed up on Grant Street, the first person would say here comes the ladder man it's going to rain. I don't know if that was true or not. There was also a rag man from Waltham, a likeable little fellow. He had a horse and wagon that went around. He picked up all the rags and bottles, and we kids would try to find bottles because he would be around on Saturday and we would try to sell them to him for 2 cents a bottle. More pocket money.

We would shoot over to Johnny Bart's store. His name was John Bartolomeo and he had a fruit store across from the depot. There were four stores right along there on Thoreau Street, Whitney's Meat Market and Bryon's Grocery store in one building and Cutler's Grocery store and Johnny Bart's fruit store in the other. That's where we bought our food. Johnny Bart's had penny candy and ice cream. He was quite a local character.

Concord was sort of divided into sections. "Back of the depot" was the area I told you about, and further up Sudbury Road near Riverdale Road was called Hubbardville. There was a man named Hubbard that used to live there originally. That area went all the way up Fairhaven Road and Potter Street. Then up Thoreau Street around Willow Street and those side streets was called Herringville, and we called the people Herring Chokers. They probably came from Nova Scotia. Then there was the East Quarter, which was down Old Bedford Road and that area. They were all separate and they all had their own baseball teams.

Baseball was a big thing in those days. The town team was managed by Al Wilson, who started Wilson Lumber Co.. Everybody in town liked Al. The big rivalry was Concord and Maynard. When those games were played, everybody from both towns was there.

Dr. Titcomb lived on Sudbury Road, and in the winter time he got around in a horse and sleigh. He drove like a madman. When he could, he would get Ed Haley to drive for him. They would have a big bear rug over their knees. I remember a time when they went around Snow's corner downtown wide open, and the sleigh tipped over. That was quite a sensation in town for a while.

I remember Billy Craig, the first chief of police. He used to sit on the fence rail at the First Parish Church and watch the town. He was a short, fat fellow and well liked. After him came Bill Ryan, and after him came Bob Kelly, then Ed Finan and then our police chief now, Bill Costello. All good men. And incidentally, I was asked to be a special police officer back in the 1930's, so I worked with every chief of police in town up to this point with the exception of the original chief, Billy Craig. I'm very proud of that. I did a lot of police work and enjoyed it very much.

Billy Cross was the town clerk and he ran a dry goods store down on the Milldam. He was a wiry, little fellow with a white, bristly mustache and white hair. We used to have to go into his store to get our hunting licenses. That would be about where the Mary Curtis Shop is today.

Judge Keyes was the judge of the local court. He had a Stanley Steamer. A very fine man but considered a very severe man. I recall one time in particular as a boy, we had a big sleet storm and every street in town was covered with ice. Judge Keyes took two ropes about 30 feet long, tied them to the back of his car and drove all over town. The kids would grab those ropes and he towed them. It was amazing to me that the very famous judge would do a thing like that. He was as human as could be.

There was a Chinese laundry where the Christian Science Reading Room is now. Those people really lived all alone. Nobody knew much about them. They had a couple of bunks in the store. You would go in and get your laundry and you better have your ticket too. They eventually brought over a young boy from China and he lived with them. There were 3 or 4 of them that lived there.

Herb Neeley had a big paint shop in the blacksmith's yard which is now Wilson Lumber. He was truly an artist. He would paint these carriages very fancy with little pinstripes. Down beneath he had stored a fantastic collection of beautiful carriages. We used to play on those, playing hide-and-seek. We used to play in the lumber yard, blacksmith's yard, and the coal yards. That's where the Stop & Shop is today. The little office is still there where they weighed the coal. That building is the little building that I used for a real estate office for years and is now a food shop.

A lot of people had one or two cows in those days. In the blacksmith's yard, there was a barn. And in that barn, a fellow on Sudbury Road, Daiglan Curran, had a couple of pigs and cows. A lot of the neighbors including my family bought their milk from Daiglan Curran. He milked the cows right there, and he poured it into these big containers and then into your quart bottle or two-quart can for you to buy. It wasn't pasteurized, it was really fresh milk. We bought milk every evening.

In those days, all the young people through the winter became occupied with shows and various organizations particularly the Ancient Order of Hibernians. We used to put on minstrel shows down in Monument Hall. A minstrel show had all kinds of acts, people sang and people danced, and through it all there was a great deal of merriment generated to a large extent by what we called end men. Those were supposedly negroes but they were white people with their faces blackened. I was an end man many times and so was Terry and John McHugh and Tommy Tombeno. We had to do special numbers maybe a little dance or a tambourine act or sing, and all through the show there was a continuous line of jokes. Simple little jokes which at the time were appreciated and enjoyed, but today you would laugh at them for their simplicity.

Between all of us people "back of the depot" I never saw any feeling of I'm better than you are because I'm Irish, or I'm Italian, or I'm a Swede or Norwegian. You had names that you called each other as boys but there was nothing to it. They might say you "thick harp" to an Irish kid or you "guinea" to an Italian kid or "square head" to a Norwegian but it wasn't taken seriously.

The only thing I recall as a boy that bothered me was at every circus or carnival they had a booth called the African Dodger. It was nothing more than a canvas hanging there with a hole in it and behind it was a negro man, who would stick his head through the hole. The cry of the barker was "hit the nigger on the head". They would sell three balls for 10 or 15 cents, and you would throw balls at this negro. When you threw the balls he would drop his head down, and when you were finished he would taunt you trying to get you to buy more balls. He was hit many, many times. I never liked that; it seemed degrading and abusive.

I wrote a poem about my neighborhood in 1975 for Mrs. Herman Hansen's 89th birthday. Among all the depot crowd, when anybody dies everybody comes from everywhere to the wake that is usually held at Charlie Dee's. The Hansen girls thought about that and their mother being 89, and they decided to hold a party because the only time the old depot crowd got together was at a wake. They sent out a simple little announcement to a few of us, and we were to pass the word to anybody of the old crowd. Strangely enough there were over a hundred people at that gathering just one telling the other. They held it at the Buttrick estate because Mrs. Hansen's son-in-law worked there. One of the fellows asked me if I would write something and I did.

Remember when we were little kids

So many years ago

Playing run-sheep-run & steal the eggs

Behind the good ol-Depot.

The kids today sure miss a lot

Tho they'd think they had it hard,

If they, - like us, - were forced to play

In Wilson's Lumber yard.

Remember hiding in the carriage shed?

You do? Then tell me, - really,

Wasn't he the nicest guy,

The owner, Herbert Neeley.

Did you every hide in the freight cars?

Or tell me - if you can,

How many times you stopped to watch

The Blacksmith, Tom McGann.

Pound sparks from out those glowing shoes

Then dunk them in a barrel

To fit them on the big gray horse

Of grouchy ol Fred Farrell.

Can you hear the hurdy-gurdy

The gypsy used to play?

Can you feel the smoothness of the eggs

Our chickens used to lay?

Do you remember Daiglan Curran?

A tough old man was he

I remember too, Dave Carey

And his famous Model-T.

Remember Arthur Loftus

And his kittens hangen dryen,

I remember too - that rascal,

Fun-loving, Rats O'Brien.

My father & Bob Woodlock,

My, how they loved their dancin,

They'd play awhile, then with a smile

They'd call for Herman Hansen.

Who'd grab the old accordian

And though it had it's faults,

With Herman playing softly

It made them want to waltz.

Remember Thomas Flannigan

And how he used to play

At 'Kitchen-rachets' all night long

Until the break of day.

Remember earning pennies

Then cross the tracks we'd dart,

To spend them all with our old friend,

Beloved Johnny Bart.

And if we got to raising Cain,

We'd hear our mothers call us

And warn us not to be so fresh,

Don't pick on "Chickey" Wallace.

Don't tease the poor old rag man

Don't laugh at old Pat Hayes

Respect their human failings cuz

They've all seen better days.

I remember Charlie Brickley

And Mike Mullaney, too.

And happy Johnny Barry

And I'll bet that you do, too.

I remember big Tom Hanley

And how he played the drum

I remember Boxer Daley,

No bigger than your thumb.

I remember Emmy Nelson

Cutting meat at Whitney's Store,

And Rosie Quinn's another one

We won't see any more.

For Dick Hartnett & Gus Jensen

You've a tender thought, I know

And we all recall with pleasure

The rambunctious - Fanny Crowe.

And Mrs. Hayes' laughter

You'd think she had no care,

When she came out from her ironing - just

To get a breath of air.

Oh, those were all good people

And when all is said & done

The life they led was rugged but,

They had a lot of fun.

Their kids were all respectful

No pot, no booze, no beer

Cuz those that dared step out of line

Got belted on the ear.

The 'Cattle Show' is long-since-gone,

Apartments took their toll

There's darn few left in Concord now

Recall the cellar hole.

We were like a great big family

Who danced & played & sang,

And I'm proud to have been a member of

The good ol Depot gang.

But I'd like to hear just one more time

Those crossing bells aringing,

Or hear again the off-key voice

Of some ol codger singing.

Or stand back in a corner

Watching dancers make their turns

Till they stop at last to catch their breath

And call for Paddy Burns.

To sing his little ditty

And this is how it ran,

Go back into your memories

And join me, if you can.

Shake hands with your Uncle Mike me boy

Shake hands with your cousin Kate

And here's the gurl you used to swing

Down on the garden gate.

Shake hands with all the neighbors

And kiss the Colleens all

You're as welcome now as the flowers in May

To dear ol Donegal.