Ilse Plume

Interviewer: Michael Kline

Date: June 3, 2013

Place of Interview: Concord Free Public Library TrusteeÂ’s Room

Transcriptionist: Adept Word Management

Click for audio, part 1, part 2, part 3.

Audio files are in .mp3 format.

Michael Nobel Kline: 00:00:02 Okay, so today is June 3, 2013. We're in the Trustee's Room at the Concord Free Public Library, and it's a rainy spring day outside—early summer day. Would you please say my name is and introduce yourself? I'll hold it. Thank you.

Michael Nobel Kline: 00:00:02 Okay, so today is June 3, 2013. We're in the Trustee's Room at the Concord Free Public Library, and it's a rainy spring day outside—early summer day. Would you please say my name is and introduce yourself? I'll hold it. Thank you.

Ilse Plume: Oh, okay. Good morning. My name is Ilse Plume.

MK: And your date of birth please. We don't ever ask ages but—

IP: (laughs) November 5, 1944.

MK: Maybe you would just start out and tell us about your people and where you were raised.

IP: Okay. Well, I have kind of an interesting back history, I guess. My family comes from Latvia, and my parents were from Riga, Latvia. They had a very difficult time during the wars and had to leave their country and make a new start, I guess you would call it. For me it was, of course, lucky because I was not through the First World War and the Second World War as my family was, and I came to this country. We emigrated in the 1950s through Ellis Island, as was the common situation at that time, and we settled in Philadelphia. We lived in Philadelphia for many years, and there was a large ethnic community. All kinds of peoples were living in Philadelphia at that time, so you had the Italian people and the Irish people, not so many Latvians, but we were a small group of Latvian immigrants. There was actually a Latvian church that had formed where people were able to carry out their folk heritage and their Latvian songs and their Latvian cooking. There was a Latvian church with a minister and so forth.

MK: A Latvian church?

IP: Yes, and it was—. Most of Latvia was Lutheran, and a part of Latvia was also Catholic—I think the northern areas—but we were a Lutheran family, and so there was a Latvian Lutheran church in Philadelphia at that time with a minister. As part of that, there was a Sunday school, and during the Sunday school, the Latvian language was taught to the children because, obviously, there was conflict, as with many immigrant peoples coming in. How do you deal with this? Do you teach the children the new language and immerse them in English? Or do you just try to keep them at home and speak Latvian at home? How do you make this transition? And I guess I was one of the fortunate ones in the sense of maintaining the heritage, because my grandparents lived with us, my mother's parents, and they basically took care of me while my parents worked. Because of them—and they didn't speak English—I was in a situation where I had to communicate with them, so I could speak Latvian at home and English at school.

00:03:32 For me, school was very difficult—the beginning of school—because I was thrown into the situation not speaking any English, and it was very frightening having just come from a situation where there was a war, and people were frantic and so forth. It was stressful. It was a stressful time, I remember. At recess, I didn't really know the other children, so I would just kind of basically tune everything out and walk around the building, hoping I was invisible (laughs) because I didn't really know how to connect with the other kids, and they had their games and their songs and things that they knew, and I was like a little alien that had dropped from somewhere else. So it was very difficult, and my parents chose to dress me in sort of an ethnic way, so I had the long braids, and I remember in the winter having long stockings. People, I guess, in Europe still wear the long, woolen stockings, and I was so embarrassed because people had bobby socks. I remember just before getting right to school, I would kind of find a little corner to pause, and I would roll down my little stockings so I would look kind of like I had little sausages around my ankles. (laughs) But it kept me thinking I looked like everyone else because that's what children like. They like to be part of a group and not stand out in some peculiar way.

Later we moved from Philadelphia to Iowa, and it was basically because my mother found work in Iowa. She was a medical doctor, and a person that she had known in Latvia—a gentleman and his wife—worked there, and at that time it was easier to get a position if you knew of somebody that was also working there.

MK: She was a doctor?

IP: Uh-huh (affirmative). And we ended up going to Iowa, which for me was very, very difficult because even though it was a change to come to Philadelphia, there was, as I say, a strong ethnic group of people from many countries, and somehow you felt part of this large melting pot; whereas, suddenly in Iowa, I was more than an alien. (laughs) I was just I don't know what because a lot of the people had never traveled. A lot of people had not only not gone to Europe—at that time it wasn't so common. A lot of people had never even left the state or had not left the town, so here was somebody like totally dressing weird and speaking with an accent. Where did this strange thing come from? So again, it was a transition and trying to blend in. And I think actually, looking on the positive side, it was probably those early years that formed my artistic sensibility; because I think when you're feeling very alienated and apart from everyone else, you look to things that are of comfort or things that you can do or can excel at, and I think art was something that I gravitated to early on. My mother was very fond of art. My father was a lawyer, but he also was a photographer. That was even more than a hobby. I think if he had been able to make his money just being a photographer, he probably would have chosen that path. He was very sensitive and artistic, and I kind of gained that from him, too, I think. But in any event, I think I formed this attachment to art because I felt like I could do it, and it brought me comfort and joy, and people seemed to like it. So in the early years in elementary school, I was the little kid that got to cut out the daffodils and paint the autumn leaves or whatever for the bulletin board. So people would kind of make comments about that, and my parents both had been very into the arts and photography and sculpture and music. My mother actually had gone to the conservatory and studied piano, and she was just very into the musical world and knew all the operas.

MK: 00:07:57 Was this in Lithuania?

IP: In Latvia. In Riga.

MK: I'm sorry, Latvia.

IP: Yes. In Latvia, it was very—. Latvia was a very cultural and intellectual center. People really—. My mother grew up in a situation where she was well off, and she—. They had a home in the country and a home in the city. In the wintertime during the season, they would attend the opera every week. That was just part of her growing up, so she knew all the composers and really just reveled in classical music, I think. My father did, too, but not perhaps to the extent that my mother did. In any event, they were very encouraging in terms of my art and my expression to keep working in that manner. Anyway, the years in Iowa were difficult for me. In high school, we moved to Des Moines, which was the capital up there in Iowa, and I went to a Catholic school. Partly that arose because one of the ministers in that church school was a Latvian priest. It was someone my father had known, I believe, and I had a very good experience there. My family, as I say, was not Catholic, and they were a little reluctant. And I guess that was my form of early rebellion. I said, "Well, I want to go to this school." And so again, I majored mostly, I guess, in high school you don't major in a subject, but art was my favorite thing in high school. And then in college, I continued with the art, and I guess that's what brought me to eventually do the children's books. Can we stop for a minute?

MK: Yes.

IP: Am I rambling on too much?

MK: Oh, no. This is absolutely perfect.

IP: Okay.

MK: Before we go any further, let's tie up some of the loose ends in Latvia. Can we do that?

IP: Okay. Well, as far as I know, I—. And most of the time when I was growing up, it wasn't a free access to Latvia as people can go there now. During the time when I was growing up, it was still a Communist country, so people didn't go flying off to Riga or any of the other countries. Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia were essentially off the map. They were part of the Russian Empire. And my parents were very pained by the whole situation, and they very seldom spoke about it. So I had a very, not a very complete history of what was really going on at that time. And at the same time, you have to understand as a child I'm just trying to amalgamate this new culture and trying to deal with what's going on in my everyday life, whatever it is, in first, second, third, fourth, fifth grade. So I'm not really that interested in hearing about this old country that no one ever heard about. And especially when I came to Iowa where there was not such a diverse group of people from all over the world, it was just very difficult and painful to be sort of part of this country that nobody seemed to know anything about—not even able to pronounce it—and to somehow—I think in my own mind, I was just trying to put it out of my mind, if anything. So it wasn't until many, many years later actually when Latvia became free and people could actually visit that trips started, families wanting to see their country and their homeland again.

My mother chose not to do this. She had such beautiful memories of a young woman growing up and the homes that they had there, and she knew everything was changed, obviously, because of the war. It was just very painful for her to go back. I had tried to arrange a trip so that my daughter and my mother and I could all visit together. And the first time that I tried this, they seemed to be interested in the beginning. And then when it actually came time to buy the tickets, everyone backed out. My mom said, "No, no, I really can't do this." And my daughter said, "Well, I don't think I can do this either." And I became kind of cross because I'd kind of tried to make a plan, and I just decided to go by myself. So I got my ticket and went not knowing what to expect. I had communicated with some relatives on my father's side. On my mother's side, the relatives were all gone. So I was able to make contact with relatives from my father's side of the family, and they were very interested in my coming to visit them. And so I was just very happy to arrive there. Once I got there, it was very interesting. I think the most astounding thing, of course, was being able to hear the language being spoken around me. I hadn't had that until here I am a grownup with my own child and never been in a situation—whereas, for example, I'm thinking many people from Italian backgrounds went back and visited Rome and Naples and Florence and were welcomed by other relatives, and everything probably was much the same. They heard the language growing up and through various trips they might have taken, whereas for me it was just like—again, you know--landing someplace and then having a connection but yet not. So it was astounding to be walking down the street and hearing Latvian spoken, and oh, my gosh! I know what they just said. You know, because that was obviously something I'd never experienced before. The relatives were very helpful and showed me around.

MK: 00:14:23 Because of your—because of your association with your mother's parents—

IP: Or of my father's.

MK: Your father's parents in Philadelphia—that they were non-English speakers, and they practically raised you, so you were familiar with the—your mother's—the grandparents in Philadelphia.

IP: Those were—those were my mother's parents.

MK: Your mother's parents. And they—?

IP: But when I went to visit in Latvia—.

MK: But they were non-English speakers?

IP: Yes.

MK: So you'd had a lot of exposure to the language as a young child.

IP: I had. Yes, yes.

MK: So it sounded familiar to you.

IP: It did sound familiar because that was something that was spoken at home. But not in the context of getting on the school bus and people are chatting in Latvian or being in a restaurant and recognizing—you know. So in that sense, it was a whole culture that here people were speaking. Although by this time, the national language for years had been Russian. It had been imposed on the people. That that was the language that they were to learn. But people still carried on. They were very independent and wanted to retain their own culture, and so language was kind of—. I guess the Latvian language was second. But really in most people's hearts, it was their first language still. But anyway, so it was interesting to be able to hear the language. And then for me, the most interesting thing perhaps was to go back and visit places where my parents had lived because until that time, I'd had no opportunity. And while my mother at some point—. As I say, they didn't talk very much about the years in Latvia because it was very painful for them. But every so often, really happy things would come out like going for horse-drawn sleigh rides in the winter and going to the opera. My mother had very many fond memories of being on the farm. My grandparents had a farm, and so that was just something that, that it was interesting to actually physically see the land and see where she had grown up and the little stream that ran through the property and the wildflowers and all of that. But painful at the same time.

00:16:41 So anyway, on this trip, it was very interesting and nice to make this connection. And then the following year, actually, my daughter did want to see it and was interested in coming with me. My mother still felt like she could not come. And so we went to visit—my daughter and I—and that was again very interesting because she, of course, was even one generation removed from that whole thing and really only had her grandmother's stories to kind of get any sort of sense of what the place was like. So I think it was very interesting, and when I—. Years back when I had gotten married, my husband was not Latvian. I think there was, there was a lot of pressure in our ethnic communities to try to marry someone from the same culture, which didn't happen in my case. Later I could see why because my now ex-husband was not very interested in any of that past history, and he said, "Well, we're in the States and you should learn English, and our daughter should learn English." So it was just very difficult for me to maintain any kind of cultural on-going process with my daughter in terms of the language and so forth. And I did attempt it many years later after I was divorced and had her in a Latvian school for a while and got a Latvian tutor. But I think by the time you're 11 or 12 or 13, as a teenager that's not your main focus, and so I think I failed miserably in that. That's my one regret, that I wasn't able to go forward with that for my daughter. But the interesting thing is that she—and I think, again, because of my mom, her grandmother—she was very interested in learning how to cook, and I'm not much of a person that's interested in that at all. So I was just very surprised where this came from in her, but she learned to make a lot of the Latvian ethnic dishes, and some of them are very time consuming and take like a day and a half or whatever. So there's especially a wonderful dish that's made every—like for a birthday—called a klingeris, and I can spell that—K-L-I-N-G-E-R-I-S. It's a sort of sweet bread with nuts and raisins and uses a lot of saffron, so the product is this wonderful yellow color, and it's made in the shape of a giant pretzel. And then you sprinkle powdered sugar over it. It's really quite delicious, but it takes three risings of the yeast to make this thing, and so she's really kind of put forth an effort. And especially during the last couple of years before my mom passed away, Annie would come and make that pretzel birthday cake for her, for her birthdays. So that was very nice, and other dishes as well that she made. So in some ways, she did perhaps retain some of the interest in that culture in a different way, not through the spoken language.

00:20:11 And then when we went back—my daughter and I—we were able to visit both my mother's land—her property where she had lived and grown up—and my father's as well. So that was really an interesting part of the journey. And just to—. For me as an artist just to physically see the land and the people and how that all worked together was really fascinating.

MK: Did you travel with a sketchpad?

IP: (laughs) You know, I didn't because I just took lots of pictures. I think it was because there was so much going on—just the talking to the people and meeting them for the first time in some cases—that there really wasn't time to sit around and be doing that. And we just were kind of on the move because places were distant, one from the other, so we were in the car a lot. And then there was mealtime where we would be eating and just talking. I think that was the main thing, just wanting to connect with the relatives and speak with them. So that was just a wonderful part of it. And my daughter, actually, is a good photographer, which is interesting because that, again, hearkens back to my father. And she took a lot of photos of that journey and then made them into like a little calendar for all of us to look at, and that was really a special thing. Can we pause again?

MK: Yes.

IP: I just need some—.

MK: So these trips back to the motherland must have been life changing for you and your daughter, and I'm interested in what effects this had on your art.

IP: 00:21:59 You know, it's interesting because I think that all of us are influenced somehow through our own personal histories about the art that we produce as artists, and I feel that even before seeing Latvia I had a very strong sense of the patterns and the colors and the flavor of that country, and I think because there was a lot of arts and crafts that came from Latvia—especially in some of the blankets, the woolen blankets with the patterns and the designs and curtains and bedspreads and woolen items, you know, like mittens. I wish I'd thought to bring some Latvian mittens because they were just so beautifully made, and shawls and things that the people wore and jewelry—through their love of jewelry—and I think that all of those things influenced my art, because a book that I created called The Hedgehog Boy, which was actually a Latvian folktale, I did before I ever visited Latvia. But then I realized afterwards that my choice of the colors and the borders that I used in the book were basically things that had been patterns and designs that I might have seen on blankets, and I bordered all the pictures with patterns that I would have seen had I looked at the shawls and the blankets and so forth. So that was just a very interesting tie in, and when I had that chance to visit Latvia, then I sort of saw where all these things were coming from. Before that, I never really paid much attention to it. I just kind of drew what was in my mind, and later then I thought, "Well, yeah, I've seen this on mittens, and I've seen this on woolen blankets," and I sort of am very fond of borders because I think that they bring another element to the pictures and that they have a way of encompassing or bordering the artwork and putting another stamp on it, perhaps an ethnic quality, which other people wouldn't have in their work.

MK: So The Hedgehog Boy was a Latvian folktale that you had heard or read or—

IP: Yes. My grandfather—I was very fortunate in that, as I say, when we came to this country and everyone was scrambling for jobs, it was such a hard transition, as for many immigrant families. I don't think we were any different or special in that regard. Most people that came— whether it was from Ireland or Italy or whatever—suddenly were thrown into a different situation where they had to make a living and had to survive, and they did the best they could. For example, my grandfather had been a bank director and a customs official, and [here] he was in a factory, working in a factory—labor—heavy, heavy labor. My grandmother was sort of left with tending the household. My mother went back to medical things, and my father had difficulty finding a job as a lawyer, so he was a bookkeeper and a person who worked in the office. He still spent time with his photography, but I think that the transition was much harder on him than it had been on my mother. And he was of a weaker constitution. He had health problems, and so it was just a family struggling to make good in a new country and trying to survive, I guess, by whatever efforts they could muster. So I lost track of my conversation.

MK: And the names of your parents were—

IP: Oh, my mother was Alice Purins—P-U-R-I-N-S— Plume. And Plume in the Latvian context is pronounced ‘Ploomeh,' and it means ‘the fruit', the plum. So it doesn't mean, as in French, ‘the feather' or whatever other connotations. So it's just the fruit tree and the plum of the fruit tree. And my father's name was Richard. And both of them had grown up in Latvia. I think my father also had grown up in Lithuania part of his early life, because he had connections to both countries. They were both, as I say, intellectual in many ways. My father spoke Latvian, German, French, Polish, and of course English and Russian. My mother spoke Russian, German, English, Latvian. And my grandparents I don't think spoke as many languages.

MK: 00:27:21 Their names were—

IP: My mother's grandparents—Emma Purins.

Carrie Kline: Mother's parents? Your mother's—

IP: My mother's parents were Emma and Janis—J-A-N-I-S—which is John in Latvian. Purins—P-U-R-I-N-S.

MK: And does that have a meaning? That name?

IP: No. Purins would be just a name like Kellogg or something. It doesn't—.

MK: Like Smith or Jones?

IP: Yes, yes. It didn't have a specific name. Yeah. And they were very traditional Latvian names. Like my name, Ilse is very traditional. It's—. In Latvian, it's pronounced ‘Eelzah,' so there's a Z element. And somewhere along the way, because I actually had been born in Germany on the way to the States, and so on the German passport. I don't think in the German language there is a Z in that context, so it was made into an S, so it's on my passport as an S. And it's actually very interesting because many people I meet today—. And I've always gone with the name in that fashion, and very many Latvian people are very offended by that because they feel that it's kind of taking liberties with the name, where it's the traditional spelling should be with the Z. And I always try to explain, well, it was on my passport, and it just was easier to keep it that way. But when I'm in Latvia, they still pronounce it with the Z. So not so much in this country.

CK: And what do you—? How do you pronounce it?

IP: It's Ilse, but in the Latvian it's Ilza. So there is the difference, you know. And if one didn't know, you would think maybe it was a different person altogether, and I've many emails about it. (laughs) So it's just kind of become an interesting thing, but it's all right.

MK: Well, I guess there was a lot of that going on on Ellis Island, people's names getting shortened and changed.

IP: Yes. Well, that's right, too. That's right, too.

MK: 00:29:31 I would find that very offensive.

IP: Yeah. It is something that's very interesting though.

MK: It's like a butterfly, I guess, coming from a moth and shedding its—or coming from a caterpillar and shedding its old skin and having to re-bloom.

IP: Yes, that's right.

MK: Bloom where you're planted.

IP: Yes, yes.

MK: I always was very offended that, in talking to immigrants, that there were those name changes.

IP: Yeah, there was some interesting movie some years back about that, and I don't recollect the name of the movie, but it was talking about all the many people who came and were forced to change their names and so forth against their will, more or less. And of course, some people did it happily. They thought they—. Again, it was part of some people wanting to blend in, and the shortened version of their name, or the different name altogether, was more in keeping with their new identity. So actually, it worked both ways. Some people did not mind, but I think a major part of the people did mind.

MK: So were you an only child?

IP: I was.

MK: Okay.

CK: You were what? I'm sorry?

IP: Oh, an only child. I always wished I had brothers and sisters. And as a child, I did make up imaginary playmates, which isn't that different from most other kids growing up who were lonely in their—. And as I said, I was especially lonely in my childhood because I didn't really make friends easily. And especially after we moved to Iowa, it was difficult because there weren't that many people around. I was fortunate. There was a young girl up in my grade at school who also was from Latvia. So we at least had that in common, and I remember some of the early outings that we took with families together, like to the Latvian church and to different Latvian theatre events. So at least I did have this one comrade in arms, so to speak.

MK: Well, let's see. You had told us earlier that your interest in art continued through high school.

IP: It did.

MK: And then where did you go with—? Did you continue to study art? Or were you just a naturally-formed artist for it?

IP: 00:31:52 Yeah, you know, I did. I mean, all through high school, that was the one class I looked forward to. And whatever it was that was, whether it was some sculptural piece or whatever, I was very involved in that. Then when I went to college, I actually went to Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa, and it was not a school specifically known for the art. It was—. It had a really good art department, actually. But most people, when they think of Drake, they think of the—. It's a business college, and also it's known for the Drake Relays, which was a big sport event. But I had gotten married right after high school, and my husband at that time had a scholarship to Drake; and therefore, it was where we were centered and where we lived. And I just—. My mother, as I said—. My parents coming from this very intellectual background just were kind of horrified to think that my education would be stopping because most of the time people got married and then took care of the family and—in those times. You realize this is back when, in the prehistoric times, and people did not go to college that much after they got married. But I think because of my parents' devotion to education—especially my mother—she just thought, well, of course you have to go to college. That's just a necessary thing. And so they would—. My grandfather—. My grandmother died, but my grandfather would help me out and take care of my daughter when she was born and allow me to go to school. And I started by just taking a class here and there and finding, oh, I can really do this. I was astounded of myself. But I think without the familial support, I would not have ventured out into that realm because, as I say, back then—in the ‘60s and so forth—people weren't into that so much, especially young women who had just gotten married. So my husband and I moved to the married student housing at Drake University, and both of us were taking classes.

MK: What were some of the early courses that interested you?

IP: I started out with just taking art courses, and I think one of the first courses I took was a painting course, and I was just petrified because I had—. After all, I had taken a little bit of time off, had my daughter, and gone back to school. And here were all these young kids—seemingly Freshmen—and here I was already a mother, and I felt really awkward and insecure about my own place in that situation and found it very difficult and was very insecure about my ability to perform and was just petrified. But I took my first class, and the teacher was very helpful, and I found at the end of it that I'd gotten an A, and I thought, "Oh, wow! This is really great!" And so I continued taking other art courses.

And eventually, I think, when my daughter was maybe three or four, I found a wonderful, wonderful school, and I was just amazed at this school. It was called Miss Dell, Miss Dell's Nursery School and it was in the middle of Iowa, and you don't think of that community as being all that progressive. And most of the church or the little schools that I saw were either church schools or schools that were in somebody's basement where a couple of people got together in the neighborhood and said, well, let's have a place for our kids to go while we're doing whatever. And this was actually a certified school, and the woman who began it was this little spinster lady who had a degree in psychology and education, if you can believe it. And she was very dedicated to children, and this little place was just in the middle of the city. It had—. It was like a little gingerbread house, and it was all garden, and on the outside it had a high fence so the kids wouldn't run away or get lost in the daytime. And she had a structure to the day so the children came and they had some sort of classes in the morning where they learned the alphabet or whatever, you know, preliminary things. And she even—. This was so astounding to me now, looking back, and I hope my daughter realizes how special this was. There was even a book club. She had a book club, she ordered children's books that she had researched that were good children's books, and each child had an option to buy the book at the end of that week or something. There were new books every week, and you didn't have to buy them. Nobody forced people but that—. Each week there was a special book that she would read to the children. And of course, maybe it was somehow tied in with her plan, and I'm sure there was a financial aspect to it, obviously. But at the same time, it was such a wonderful educational tool that she was offering these children, this love of books. And then there was a certain time when everyone had juice, and then there was a nap time. Each child had a little mat, and they were able to lie down and rest in the afternoon when it was hot. And so there was a very structured, wonderful kind of school, and I felt that at that time that I could go back to school. I wasn't just dropping my daughter off just any old place. I felt like this was possible, and so I then signed up and did a regular semester's work, in other words.

00:38:01 And it was hard to cope with the homework, though, because art—. Most people don't realize how long art takes. (laughs) It's a little different than—. You know, you study math, of course, and that takes time. And then you learn your formula and your problems and so forth. And then you have the test and you're examined. Well, with art, each step of the process, whether it's something like printmaking, takes an enormous amount of time, both in class and outside of class. So you have to get all that work done, and I found that I would be—. I was a night owl in those days, and I found that I could stay up until two or three in the morning. And so my daughter and my husband would be sleeping, and I would be out in the—. We had a living room that had a—, well, part of it was a dining area. So I had a big table I could spread all my artwork on. I'd take all the dining dishes away and put all my artwork out on the table, and it was the quiet and peaceful time of day, no chatter of children and no problem solving and no talking to my ex-husband, well, now my ex-husband. So it was a peaceful time where I could get energy and work. And it was very interesting because coming from a family that loved classical music, the only station that was on in the middle of Iowa in the middle of the night was WHO, and it was a country station. And so I got familiar with Johnny Cash (laughs) and all the people that were Hank Williams and all the songs that they played. And so I actually love country music today, and it was because of those, all those nighttime hours of trying to get my art project done for the next day. (laughs) And spending time with Dolly Parton and Johnny Cash. (laughs) Can we take a break? (laughs)

MK: Yes.

IP: I guess that's silly, huh? (laughs)

MK: 00:40:00 You were describing plate—.

IP: An etching, yes.

MK: —etching. Uh-huh (affirmative).

IP: One of my favorite art forms became printmaking, which I took in college. And printmaking has many definitions and many types of artwork involved in it, and one of them is a woodcut, for example, where you cut into the wood and then ink that piece of wood and print it on a piece of paper. And the other form that's really popular is called an etching, which is done on a metal plate. And so what I brought today to show you is an etching of a picture, which I used later in one of my books called The Story of Befana, who is in Italy the Santa Claus of Italy. So instead of Santa or Saint Nick, you have a little character called La Befana, who is a Christmas spirit. In this country, they call it the Christmas witch, but I think that's actually a misnomer. I don't think that's a correct way to explain it because she's this kindly, gentle spirit that comes and brings gifts to the children at Christmas in Italy—and all over the world, I guess—and then puts coal in the stockings of the bad children. But she's certainly not a witch, and I think, as I said, I don't think it's aptly named.

But because I love printmaking so much, a lot of times when I begin a process of creating a book, I actually used to make an etching first, which then later I did a colored pencil version of that image. But in this particular image, which is the etching, you have a metal plate which you then put a ground on it. And this ground is kind of like a tar-based substance. It smells like tar. It feels like tar. And you—with a roller you—or with a brayer you gently cover the whole plate with that tar surface. And when it's dry, you take an etching tool and you draw onto the plate. And you only, of course, scrape away the part that you're drawing on. And the rest is that ground that you put on it. After you put that—. After you scrape into this plate leaving the rest of it intact, you then put the whole plate, the metal plate, into acid and the acid eats away at the part you've scraped so the line—. That's what makes the line come through. And it's a very long process, and you have to time it. You have to put it in the acid and then pull it out—kind of check it—put your fingernail on it and see if it has etched a groove in there or not, and you just keep doing this until you feel like it's—. The timing is crucial. Once you think that the plate is ready, you then have to wipe off the tar surface. You put ink on it—again with the brayer—a roller, and then you wipe the ink off with a cheesecloth. And the cheesecloth is kind of—I'm trying to think what it looks like. It—. I can't describe it. Anyway, it's just a fabric, and you roll it up and use it to wipe. You could also use paper, but it's easier with the cheesecloth. And after you wipe the plate clean, the only ink you have is in the grooves. And then you have dampened your paper. Your paper is sitting in a vat of water. Then you have to kind of dry the paper partially, put the paper on the press, run—, put the plate down. Like if this is the plate, put the paper on top of it, run it through the press, and the pressure of the press will force the ink onto the paper. So it's a very long process. But for those of us that love printmaking, it's just a fascinating way to make art—very time consuming, I have to say. And in the piece that's behind it here, which is another etching which was done in the same way, it's one step further because then I hand-colored it. So I colored it with colored pencils after—. So that if I were to color this, for example, it would take on that quality.

MK: And you call this print.

IP: 00:44:33 Well, these are etchings, and the artist proof—. Normally you number. In an etching you number it, so it's one over whatever. Like an edition would be. If you planned to make 100 of this image and this were the first print, it would be 1 over 100, meaning that that was the first of 100. Or it would be 5 out of the 100. Or it would be 22 out of the 100. An artist's proof simply indicates that you're not quite sure if you're done, and if you might want to make changes. So you call it an artist proof, and that kind of keeps it not part of the edition. And it could be either more valuable or less valuable as you see fit. And maybe you give up and you never take it anywhere so it's never an edition.

MK: And you titled it—?

IP: This—. Well, this particular one is La Befana, the first one that I showed you from this Italian folktale.

CK: Black and white.

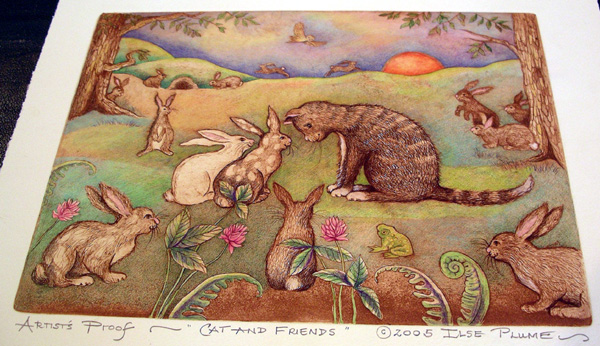

IP: Yeah, and she's feeding the chickens. And that's, as I say, an image in the book that we can find later. And this one is part of a series that I—. It did not really become a book. I have not yet written a book myself. I've used other people's words. I've used images that I've made up. And like for this book, Jane Langton—I've worked with Jane over a period of years—wrote the story. In this one, I was trying to write my own story about this cat who couldn't find a home. And then it got kind of sad and never did finish it and cat never found a home yet, but he's on his way here. So in this particular image that you're seeing, the cat goes to the rabbits here, and he says, "Gosh, you look like you're having so much fun. And I see your little rabbit hole there, and I'm just wondering if I could join you." And then the rabbit says, "Gosh, you're such a nice cat. I really like you a lot, but there's so many of us and more on the way. I just don't think there's room for you here." So cat has to move on, and so the story goes.

CK: You've got an owl at the top and sort of rainbow encirclement of it though. It's just really wonderful.

MK: Could it—could it be just a little bit autobiographical do you think—this story?

IP: Oh, you know, I think so. I think all of us try to—maybe subconsciously even—try to bring things into our lives that tie in with our backgrounds. There's a very interesting and wonderful illustrator now named Shaun Tan, and he always speaks about the fact that loneliness and being an outsider and being totally alienated from everything was what brought his art about. And one of his famous books is called The Arrival, and it's about being an immigrant and searching and moving through scary images—a lot of—part of the images are real and part of them are unreal where there are all kinds of monsters and dark things coming out of nowhere. And I do think that this also reflects on my work, and I believe that he's—. His family is from China, and he lives in Australia, and his wife is from New Zealand. And so he said he never felt like he belonged anywhere. And I think I've always felt a little bit of that. And certainly my love of Italy comes from the fact that many years ago, before Latvia became a free country and I had never seen it, and I was just at a point where I was getting—(siren sound in background)

CK: Let's wait.

IP: 00:48:34 Shall we continue?

MK: So you had never seen Latvia?

IP: No, and through my lifetime I became very lonely for wanting to have a real place. Like everyone else, like certainly here in Concord, you feel that a lot because you'll talk to somebody, and it's like it turns out their parents came over on the Mayflower. (laughs) And they've always been here. And their sense of history there, not only do they live here presently and currently and their children might go to Alcott School or something, but their grandparents grew up here and before them their great-grandparents. And it's just that history which I've always sort of lacked in my life.

And at some point before I ever went to Latvia, I just became enamored of Italy. And this was something actually that goes back to my mother again, so if I can interject that part of the story and jump up then to mine. As my mother was trying to decide what to do in life, and as I said, she had been going to the conservatory and studying piano. She was suddenly aware of a book that was popular about San Michele, and it was a story about a doctor who was on the island of Capri in Italy. And she—. The Story of San Michele, I think--. And so she absolutely loved Italy, and that came through so much in talking to her. And when her—. When she finished medical school actually, her parents had wanted to send her to Italy as a gift, as a graduation gift. And then the war came, and it never happened. But her stories later—. Because after I had left home and she took many trips to Italy and had such a love of the art, to actually see a Botticelli, a real life Botticelli piece of art or a Bellini. And so she somehow imparted all this love of art to me so that when I grew up and I just had this—I don't know—just amazing rosy picture of what Italy was without ever having been there.

So later when I did have an opportunity to go there, I just went several times, and I suddenly decided that I was Italian. I hardly look Italian, but I sort of had such a need for a country and for a place that I was from or could relate to that Italy sort of became my adopted country. And a lot of the books I found myself—and this is where we're getting back to the story of my own life—I found that I set my books in Italy. So you have The Legend of Befana, which is the story of the Christmas spirit. I set The Twelve Days of Christmas—which is certainly a madrigal English kind of song—I set that in Italy, in Florence. And so any chance I got I would move my characters to Italy. And so that filled such a huge void in my life while I was feeling not quite American enough and not feeling quite Latvian enough and—well, obviously, I'm clearly not Italian enough, but in my mind I was, in my artistic mind, so that when I went to Italy I felt at peace, and I felt that somehow it was my home. And I still partly do feel that way, and I love the opportunity to be able to go there. I usually try to go once a year because every year in the spring there is a book fair in Italy where, from all over the world, people come and partake of this wonderful exhibit. And so at least once a year I try to go there, and we can talk more about Italy later. I need a break.

MK: Now what are we looking at here? The book is—?

IP: 00:53:09 So this is just the preliminary etching that we were speaking about earlier—that I'm holding up in my hand here—which is in black and white, which I'm calling the sort of preliminary sketch. When I got this idea of the story of Befana, the Italian story--. The book is called The Story of Befana, an Italian Christmas legend. And it was first published by David Godine and actually later it was—. It came out with another company called Hyperion. And you know that's—. Speaking of regrets, I don't have that many regrets in life, but one of my big regrets was that when this book came out the second time with Hyperion, for some reason they insisted on calling it The Christmas Witch. And Hyperion is a division of Disney, which kind of explains the whole thing, I think, better. Because I think The Story of Befana is really the correct title, and I think looking back I should have stuck to my guns and said, "You know, it's an Italian story, and this is what it is. It's not The Christmas Witch." And I think people probably were put off buying it because it didn't make sense. You think of Christmas and you don't think of witch. The two words are kind of not harmonious. But in any event, whatever, this image that I first did in this format is an etching. Later in the book it became a colored pencil drawing because the book was done in colored pencils, and it's just interesting to see the difference because obviously color brings a whole different dimension to a piece. And with an etching, as you're printing it, the print was always backwards from—.So that's why it's the same image but it's flipped.

MK: Mirrored.

IP: Mirror image, yeah.

MK: Uh-huh (affirmative). Fascinating.

IP: And actually I was very fond of seeing it in this format, so I asked my editor and I said, "Well, could we just have it in black and white?" And I think because my first book came out— The Bremen Town Musicians—and that had gotten the Caldecott Honor Award, they said, "No, no, no, no. You just keep doing what you're doing." So in a sense, it kind of kept me from shifting gears and moving in a different direction because obviously if your editor tells you something—and you're new at the game—you're not going to argue with them and say, "Oh, well, no, I think it should be this." But I was, for the most part, happy with how the book looked in its final alignment.

MK: So let's back up just a little bit and review the printmaking skills you developed in your college student years.

IP: Yes.

MK: You must have had a very good print teacher.

IP: 00:56:07 I think so. And I think also as a person is going through art school, it would be just the same as any student going through some other degree preference, whether it's math or science. You gravitate towards things that you like. And printmaking, just the whole kind of labor of it, I guess—a labor of love—because it is a very time-consuming process, and some people just don't take to it, and I've had many friends—. In fact, one watercolorist that I know said, "Ew, how can you like that process? It's so messy." Because the ink and all the turpentine and all this stuff that's involved. It's a big process. You don't just jump in for half an hour. It's something that you plan to do for the day or for at least 3 or 4 hours, because otherwise it doesn't make sense to get all ready and get the ink ready and then just flit away and have lunch or something. You kind of have to be on target and be there the whole time. So I would say that out of all the processes that I learned—. And as a student in art school, in the beginning, of course, you're trying everything. So I've had some sculptural, three-dimensional things, and I've had some pottery and some jewelry making. But out of all of that, I think, probably the watercolor, the painting, and the printmaking were the things that I somehow gravitated towards.

And yet, it's interesting that when I first began children's books, I used the colored pencils. Isn't that funny? Rather than gravitating to the things that I had spent a lot of time on. And I really actually had not used colored pencils since I was a child. And part of my reason was that colored pencils are very portable. You can just take them with you. You know, you just have a box of them and shove them in your bag. And then I thought that it was something that children would use, that that was a familiar thing for children because obviously a parent would freak out if someone gave them a set of oil paints and then they ended up on the rug and the wall and the—, you know. (laughs) So I didn't think that would be very appreciated by parents. And it just seemed like a natural way. And when I first—. On my first book, which is The Bremen Town Musicians over there, that was just the first time I'd used colored pencils and the first time I put that kind of work together.

MK: And that's the book that—? Your very first one was the book that won this great award?

IP: Yeah, that was very unexpected.

MK: What was your age then?

IP: Oh, well, by that time, I had—. That's quite a story. Can we take a break?

MK: Had it not been for—?

IP: Well, had it not been for my mother's interest and her love of learning, I guess her love of education, the importance of school, and always learning. She was taking courses at the Harvard Institute for Lifelong Learning for twenty-one years. She moved here to Massachusetts when she retired, and we were so blessed. I feel very blessed to have had mom with me. She just passed away in April, so she was 98. And she was coherent and energetic and vibrant until the end so—. And her love of learning was just really amazing, and I think she passed that on to me definitely and also to my daughter. And so after I finished college, which was no small feat when you're a single parent and trying to get a college education. And then I went on to get a master's degree also in art, which gave me a teaching certificate.

MK: 01:00:11 Where was that?

IP: This was still at Drake. And then I took some courses also at the University of Minnesota. And then I studied for a year in Italy, so a lot of—. I guess a lot of school for me, too. And right now—. For a long time as I was—. I'd been teaching at the museum school here in Boston, and in the beginning years I also, at the same time that I was teaching courses I was taking printmaking courses, so I continued with my printmaking, my love of printmaking. So for about five or six years I took printmaking courses along with teaching my own course on how to do children's books. And that's something that I still do. The teaching part I—. In fact, I have a class coming up in June, from the 10th of June until the 17th of July. It's an intensive summer course. So it's meant for people who are interested in children's books, who either are artists or writers or want to combine the two and make a great children's book.

CK: It would be great to hear how you yourself got into illustrating children's books or creating children's books.

IP: While I lived in Minnesota, and that was the next step after having lived in Iowa. And this was when I was in my early years when I was married and we had moved to Minnesota. And there was a wonderful, wonderful book place on the campus at the University of Minnesota called the Kerlan Collection—K-E-R-L-A-N-- Kerlan Collection. And it was begun in honor of a man named Irwin Kerlan, and he had been a physician who was enormously interested in children's books and their creators and had started a collection. And he went on to collect artwork from all the famous people of that time and had communication with them, and I believe he resided himself in Washington, DC. But—. And sadly, he died. He was hit by a bus, I think. But he at that time had an enormous, enormous collection, which was then bequeathed to the Kerlan Collection in Minnesota. And as students at the university there, people could come and look at the collection. And I think that was what was truly inspiring for me. I think it's now called the Children's Research, Children's Literature Research Collection. It's no longer called the Kerlan. It still is at the University of Minnesota. I think it's housed in a different building.

But it really formed me as a person in children's books because I was kind of struggling with what to do with my life, and I thought, "Well, do I want to teach art? Do I want to take other courses?" I was a little bit struggling with do I want to go into journalism because I was always interested in that. And I just really didn't know what to do, so it was while I was at the University of Minnesota struggling with like what do I do next in life I found out about the Kerlan and started going there. And you could actually—. Because of this wonderful collection of children's books, you had this absolutely beautiful room with a fireplace at one end and an old wooden table and lamps and, just something that we're seeing here in Concord, but in that setting it was very special, and you could go and research all of these illustrators that I was fascinated with, whose works I loved. And I came to children's books through my daughter because I would be going to the library, bringing books home for her. And I loved looking at the children's books, and it had never occurred to me that somebody out there actually does the—. You know, you just don't think about it. You just bring the books home and look at them. And as an artist, I suddenly thought, well, why not me? I could do a book, couldn't I? And I wasn't sure, but I mean it suddenly sparked my interest in that direction, which just came out of that thought.

01:04:41 And as part of the ongoing lecture series, I guess, at the Kerlan, different people, illustrators, writers would be coming through and giving lectures each time, and so you had that ability to not only see the artwork and see the books that were generated out of that but you also had actual live people coming through that talked about their process and their work and their love of their work. And I thought, what an amazing world this is, and just to be able to step into that world seemed like such an enormous thing. And so over a number of years, I continued going there and listening to the lectures, looking at the books. So it was very interesting. You had a large table such as this, and you could write down what books you wanted to see, and they would be brought up in a cart. You had to wear gloves, white gloves, to look through the artwork so you wouldn't be touching it and putting fingerprints on it. So I got to actually look at Maurice Sendak's early drawings and look at letters he had written to his editor and she had written back to him. He had one of the great editors of all time, Ursula Nordstrom, and just the fascinating letter writing back and forth. And all of these people, Trina Schart Hyman, you know, two of these greats that we've lost in the last bunch of years. Trina Schart Hyman is gone as is Maurice Sendak. But just the ability to see countless, these and countless other illustrators' work, was just such an enormous thing to me and to read the original manuscripts of say, Marguerite Henry, all those horse books. It was just—. It was like a heaven on a tray that was like a banquet that I could go partake of anytime I wanted to, so I dropped all interest in journalism and continuing that or selling real estate or whatever else was flitting through my mind and suddenly felt that somehow this was a calling that I had to pursue this and I wasn't sure how.

01:06:54 One of the speakers that happened to come through was a wonderful illustrator/writer named Peter Spier, and he was a Dutch gentleman living in New York, and he had recently won the Caldecott for a book called Noah's Ark. So he was amazing as a person and as a mentor, and one of the people who knew that I loved children's books and was struggling and trying to figure out how to get into this world. After he came and spoke, you know, she said, "Oh, well, don't you have a portfolio here, Ilse? Can you just show Peter?" I was like so embarrassed because here was like my idol, and I'm having to show him these crummy little pieces of something that I had in my portfolio. And so I did that, and he asked me what I was thinking about doing and asked me if I was interested in doing children's books. And I said, of course, that I was very interested. And he kind of just looked at me like he couldn't figure out what the problem was. And he said, "Well, just do it." And it was before--. Now it's such a Nike commercial thing, "Just do it!" It's become blasé. But at that time, I had never heard anyone say that. And it, somehow it gave me permission. It was a funny thing. It was like something was holding me back, like I thought, okay. Maurice Sendak and Peter Spier and Trina Schart Hyman, all these famous people are out there doing this. Like what would give me the right to think that I could ever do something like this? And it was just that sweet simple way--he was a very direct, very humble guy-- and just him looking at me saying, "Well, why don't you just do it?" And so on. Really on the basis, on the strength of those words, I went back and I worked for like 4, 6 months, and I just started working on the book. And he had said, "Just do what you know and something from your past that you're familiar with," because I had no idea how to start or what to go about to do this.

X 01:09:05 And one of my favorite stories was the story of The Bremen Town Musicians, which was an old Grimm's folktale. And I think I started saying earlier that my—. I was very fortunate. My grandfather was a storyteller in the old oral tradition, and I just have always loved people who were traditionally sort of ingrained with stories from the past, and how stories pass from one generation to the next and how they might be changed or enhanced, or what happens to these oral folktale traditions in life. And so the book that he loved so much was that book. And I was somehow, again was haunted by the idea that these animals were left homeless. The grain of the story is that—in The Bremen Town Musicians is that—. Like for example, the rooster, the cat, the dog, the donkey, the donkey's too old to carry the weight he's supposed to be—you know—I guess hooked up to the cart carrying heavy weight, and he's getting kind of old and feeble, so the farmer says, "Oh, got to get rid of him." And the dog is kind of getting not able to sort of protect the land, and so he's kind of thrown out, and the cat is getting feeble and not able to catch the mice. And the farmer's wife decides, well, the chicken is ready for chicken soup. So they all get together and they go off to form a band. But again, it's that series of loneliness and abandonment. Like so what happens? And then they wander through the hillside and come across this cottage where the robbers live. And they think at first it's deserted, but then they notice there's smoke coming out of the chimney. And so they go to this cottage and peek in the windows and see the band of robbers. I guess they're dividing their loot. And so they all make their little animal noises. They kind of all stand—, which is the traditional picture that you think of when you see the Bremen town musicians. You know, the donkey is on the bottom and all the animals are standing on the back. And then they all make their sounds. The cat meows, and the dog barks, and the donkey brays, and the rooster goes cock-a-doodle-doo, and the robbers get frightened and they just leave and they never come back. So it's not a violent thing that happens. It's just that they're gone, and the animals can live there happily ever after. And to my mind, that was just the perfect solution.

01:11:39 So that's the story that I knew best from my grandfather's re-telling. And he was just such a great storyteller that, of course, he made all the sounds of all the animals. So as a kid growing up sitting on his knee, that's the one story that comes to my mind and was the strongest impression for me. And so when Peter had said just do it, I just really went home and thought, well, that has to be the story that I'm doing. So I had to think of a way to re-write it. You can't plagiarize a story, and it was certainly a story that had been around a long time. But you could also just make it a little different using your own words. So I was going to do that and just start on the pictures. And it was a fascinating thing, and that was the first time, really, I picked up the colored pencils and just started. And the very first picture I chose was the one of the animals there looking in the window, one on top of the other. And it was because I thought well, okay, so if I can draw all four of them, then I'll know what they look like for the rest of the book. Otherwise, if you start with the cat then you're sitting there wondering what the other animals are going to look like. So I had kind of that impression of how they would all look. And so I went home and I measured Peter's book. I had no idea what size to work on, (laughs) so I measured his book and I thought, well, he knows what he's doing. I'll measure his book. And that's kind of how it started. I need a break.

MK: 01:13:17 Okay, so—.

IP: Oh, I'll begin again by just explaining the end of my sort of involvement with the Kerlan and moving to New England, but I had decided pretty much that I would really love to pursue the children's books. And I decided then and there that I would just commit to that story of The Bremen Town Musicians because that was the story I grew up with that my grandfather had told so many times that I just really loved. I loved the story of, the idea of the animals all being abandoned and thought to be useless, who then got together and decided, you know, there's still life left in us. We're still going to continue on and do something. And the fact that they all banded together and made a life for themselves kind of went back to my sort of immigrant family in some way, I think. So I loved the story and worked on it, as I say, for four or five months.

And then there was a big convention in Chicago, I believe, and I went to it because being in the Midwest it was close. And Peter Spier was, I think, one of the speakers, and certainly it was just fun to see him again. And I had my little portfolio because I was just so excited. I wanted to show him all my recent things, and I hadn't realized that because of his recent sort of fame in having gotten the Caldecott Award that there would be mobs of people. So there was like a line a block long of people waiting to have him sign his book. And as I got closer to the front of the line, I felt more and more ridiculous because I had my little portfolio (laughs) here and I thought, well, this is not the time or the place or anything to do with what's going on here. But I, of course, had a book I wanted to have him sign, so I just figured well, I'll just have him sign the book and leave, and he won't know who I am anyway. And so I felt really ridiculous. And when I got to that part in the line and he was ready to take a break, too, because after being there all day they have times where they—. Somebody else like stands in for them and the person goes off to have coffee or something.

So luckily, it was approaching, and I got up to the front of the line, and he just looked at me and said, "Well, hello, Ilse. How are things going?" And I thought, well, how could this man possibly remember from all the thousands of people that he's seen. And he just said, "Well, let's see what you're doing." And I just was so amazed that he was so humble and amazing at that time in his career that he would take the time to look at my ridiculous little things. And so he took the break and looked at my stuff and said, "Great! You're doing great. Why don't you just take them in (laughs) to have someone look at them?"

01:16:14 And this was also coincidentally the time that I was going to Italy for the first time with my young daughter. And so my next step was to go to New York because that was where in those days you took the ship. And you had a big steamer trunk and lots of things that were going over there with you. And so I arrived in New York, and my mom had come to see us off, and we arrived, and I had my big steamer trunk and my daughter and my portfolio (laughs) in New York. And because there was so much going on at that time—and I was more worried about losing my passport or my daughter than I was worried about meeting publishers—that I was just very nonchalant about the whole thing, which was helpful for me, or I would have been a nervous mess and made a ridiculous impression. And so instead, when I arrived I was just fine. So I went to five different publishers and showed them my work, and luckily nobody laughed at anything I had shown them or thought that it was ridiculous, or nobody said, "Well, go back to dental school," or whatever. And so I was encouraged, and one publisher really liked the things, and they said, "Oh, well, can you leave these here?" And again, because I was so nonchalant, I said, "No, of course not. I'm not—" (laughs) I mean, here I'm going to Italy. I'm not going to leave my work. And I didn't realize that a committee—people had to actually look at it. So we kind of made a—sort of a deal where they just kept, I think, one or two, rather than the amount that I had taken.

01:17:51 Then the idea was that there would be a committee, and people would meet and talk about this and whether it was acceptable to them, you know, all the stuff in publishing, which I had no clue about. And I was just worried about, again, not losing my daughter and my passport. So I left those images there and was thinking about nice thank you letters I could write to everybody, and I went off to Italy on the boat. And it was with a group of students because the university where I had been—Drake University—was having a year abroad for the first time, and they hadn't had enough people so they opened it to people who had any connection with Drake, and I said, "Great. I can go."

So my daughter and I went, and when we got there I completely sort of got immersed in Italy and the beauty of it and just continued on with my drawings and forgot about the rest of anything. And about a month later—because back then you didn't have emails and all of that—a month later, a letter came from Doubleday. I was thinking, oh, wow, what can this be? And I was thinking, you know, if it's something that's good news, I don't want to be in an ugly place. I want to be some place that's memorable and wonderful. And if it's bad news, I certainly don't want to be in an ugly place. I need to be in a good place to cheer myself up over the bad news. So I chose to go to the Forte Belvedere, which is this wonderful place up above Florence. And at that point there was a Henry Moore exhibition, so if you're familiar at all with Henry Moore's beautiful sculptures—they're just so—they're modern and huge and these big, big sculptures. And I sat on the wall, and I looked over the city of Florence in the golden light of afternoon, and I opened my letter, and it was a contract.

01:19:57 (end of audio 1)

00:00:02 (begin audio 2B)

IP: 00:00:02 So that was how my career started. So that was pretty amazing. That's the high point of my life, I guess, almost.

MK: Great story.

IP: And it was a lovely story. And so Italy became, obviously, more dear to me than ever because of that connection.

MK: Association.

IP: Yes. Yes.

MK: So bring us to Concord now.

IP: Okay. Well, having had those experiences, I just decided that publishing, in my mind, was all happening on the East Coast. I don't know where I got this notion because, obviously, there are publishing companies all over. But in my mind, it had to be like New York or New England or something. And I had been going through a divorce, so that was why it was easier to pick up and leave at a certain point. And I just had a friend in the publishing world named Nancy Ekholm Burkert, who was an illustrator, is an illustrator. And she had said, "Well, I know a writer in Lincoln named Jane Langton. Go see her." And so I felt like I had some sort of connection, and I just on a whim decided this was the place to come. I decided because of all the disruption in our lives and the—. A good place to come would be this area.

But also I was concerned about schools for my daughter, but she'd been an amazing student so far. She went to a school named Breck School, which is an Episcopal school, a private school in Minnesota. So her grades were very good. And then she had gone to school in Italy in a Thirteenth-Century castle overlooking Florence, which was a little bit of an unusual situation as well. And so when we applied to schools—. And I think we'd applied to like Andover and Exeter, Miss Porter's, Ethel Walker—some of the schools that are in the area. I think Andover and Exeter—. She would have had to wait another semester and re-submit again. And she could—. Because of a cancellation, she was able to get into Farmington, Miss Porter's School, and so that's where she was accepted. So at that point, it became easy to move because I felt she was safe and in a good environment. And I had originally thought if she ended up going to school here, I would move to this area, Concord and Boston and Lincoln. And if she was accepted there, I would go to Hartford. And for some reason, I just couldn't deal with Hartford as a city. I just thought this is not the amazing, wonderful-looking city I had planned. (laughs) And so I thought, well, they're close enough that I could, I could still be in Boston or Concord or—. And that's why I ended up coming here.

00:03:13 And there was a place I think on Musketaquid Road here in Concord where the people needed a house sitter. I had first thought that it would be something that, at least for a month or so, I could get my bearings and figure out what to do next in my life in terms of where to live and such. And luckily for me, it turned out to be a whole year, and it was a very large estate, and there were many people in the family all squabbling over who would get what. So it was unable to be sold, I think, right away. And it gave me time, actually, to finish my second book, which was The Story of Befana. So that was kind of amazing and fun for me because I could still bring Italy along with me in my thoughts and think about Italy, even though I was having a winter in New England.

MK: 00:04:10 So that was in what year?

IP: Well, I think I came here in 1979.

MK: In '79.

IP: Yeah. Oh, do I have time for one really quick story? Or are we running out of time?

MK: Tell me a quick story. But I—. But also, if you would comment for us on the arts community here in Concord and what sort of support or affirmation that you felt from this community.

IP: Okay.

MK: If you could do that.

IP: Should I do that first and then go back to my story?

MK: Choose your own path.

IP: Yeah. Let's do that first. Yeah, when I first came to Concord—. And of course I was working at home. And after a while, I think, I don't know how it happened now exactly, but I know that at that time the Emerson Umbrella was just getting started. And that's a wonderful, wonderful center, art center, here in Concord that had been an old school. And for many years it was left alone, abandoned. A big, big thing in my life is the story of abandonment, the threads of abandonment. So here was this wonderful building that was not used, and there were many concepts, like should it be housing for elderly? Should it be condos? Should it be this or that?

And somebody had the remarkable idea that it perhaps best would suit artists in the community if it could be somehow made into an art center. And I know one of the early founders was a wonderful woman named Ellie Bemis. And her family is well known here in Lincoln and Concord. And Kay DeFord was another woman who was actually very actively interested in theater—wonderful spirit—and there were, I'm sure, others, but those were the two that stuck out in my mind as co-founders of this wonderful place. And as it was beginning and sort of worked on to be made habitable again. I guess it had been left alone all these years, so they needed a bit of cleanup to happen there and painting and what not.

But I remember I was one of the early people that saw the spaces, and I still at that time wasn't sure I wanted to be there. I thought, why would I want to be here when I could just work at home? But then they were able to convince me that it was a good place and there would be an artistic community, and other people would be there to exchange ideas and whatnot. And it indeed has turned out to be just a wonderful, thriving artistic community here in Concord that everyone loves and supports in so many ways.

But in those early days, as I said, I could walk through the many rooms and sort of decide what room I wanted, what space I wanted. Because my work is relatively small and because I didn't have a lot of money, I thought, okay, a small room with not much rent. So I chose the room that I actually have still to this day, and it's looking out over the street there—Stow Street—and I loved it because it had—. I could see the life on the street. I could see people walking their dogs. I could see children coming home from school. I was close to the library, which is such an important thing in my life, and the post office, and it just seemed like the right place. I didn't want to be looking out at the parking lot or the garbage dump or whatever, so that was, to me that was essential, like a room with a view, you know, like the Henry James book. And so it was very important to have that. And I just decided that was the place for me, and I've been there ever since, and it has grown so much and has gone through so many different directors and approaches and ideas. But it's still the wonderful place, I think, that it was spiritually and mentally--.

00:08:00 In every way it's a very supportive community. I know when my mom died that so many people came forward and came to mom's memorial service and wrote cards and letters and hugged me in the stairway. So I guess it's just been the right place for me to come. But—.

MK: And there's an active interaction amongst the artists there?

IP: There is, yeah. And we have—.

MK: And review of, reviewing each other's work? Or how does it—? I'm sure it's more informal than that.

IP: It is more informal. Like you know, you can just run downstairs and say, "What do you think of this?" Or, "How does this illustration work for you?" And I know sometimes there was—. In my new book I have a picture. It's a book called The Year Comes Round, which is a book of haiku poems. And my hardest illustration was actually the beginning illustration, which has a window frame, and I wasn't sure how to do that in colored pencils. So yeah, it's the book that's right there. If I can just show that first image. It's just—. It was a hard one because I couldn't think how to portray a window in colored pencils. So actually, I went back to my love of printmaking, and I used what's called a collograph. A collograph is just—if you can picture a wooden board, and I cut pieces of sponge, which are these images right here; and I took some yarn, which is this piece here; and I took some burlap and I—.

CK: Inside the—okay.

IP: Yeah, and I, well, I put them on a wooden board, glued them down, waited for that to dry, covered it with shellac so that little bits of it wouldn't be coming off, used blue paint and my brayer, and rolled the blue paint over this whole construction, which is called a collograph. And then printed that—put the paper—the damp paper on that, run that through the press, and that created the image. And then I just needed to make a window frame, which I did with the colored pencils. But that was—. One thing I was stuck on, too, was how to make the wooden frame and have it really look like the wooden frame. And there was a wonderful watercolor artist next door to me whom I knew because she had been one of my students in my children's book class, actually. And she said, "Well, why don't you try this," or "Why don't you do that?" So really I listened to her ideas because the first image—which now I can't remember what it was—she said, "Well, that doesn't really look like, quite like the window." And so you do get inspiration and suggestions and you obviously have the right to not choose them or not listen. But I listened, and I think it's a better book for that. And I think it came through looking more like a window than what I started with, so yeah, you do get inspiration, and you—. One of the artists might have a show somewhere, so you go to that if you can attend that, and they in turn would come to your opening. And so, like I said, it's—. We're there for each other, so it's been just a wonderful, wonderful thing to have.

MK: 00:11:06 That was a great example you gave.

IP: Oh, thanks. So just to finish up, I think I have--. My last thing was—, which is also nice because it ties us into Concord again. About a year later after I had finished my Bremen Town book and it had been published, I was still in this—at the end of the year—still at this wonderful place where I was housesitting on Musketaquid Road. And I got a call early in the morning. And you have to realize—. Like here I am in this big, empty house again, where there's nothing except me and all these burglar alarms and whatever. And in the evening if I wanted to sit and eat, like I had a huge dining room table like we have here and chandeliers and this and that. And here I'd be at the end eating my little bowl of cottage cheese or whatever. So it was again a story of loneliness in a big way, but a time where I could finish my book.

But one morning, I get this phone call like at—I don't know—4 or 5 in the morning, and I actually had not had my own phone. I think I had a mailing address and an answering service that was based in Boston. So nobody really could get in touch with me except people that I knew, and one of my friends was my friend Jane Langton. And somehow, someone must have given the number where I could be reached because I—. You know, this was not a number everybody could get hold of. So I get this call, and I'm a little irritated because it's early. (laughs) And it's also a voice that I don't know who this is, and not many people, as I said, could reach me. And so at the end of my—. It was like from Chicago or someplace, and I said, "Well, I'm not sure I know who this is." And they wanted to determine that I, that they were speaking to me. So I determined that, yes, they were speaking to me. And the woman said, "Oh, my dear. You've just won the Caldecott Honor." And it was just so amazing to me that the library—. You know, somebody that was one of the judges from the Caldecott committee had tracked me down and spoken to me about getting this award. And subsequently, I found out that that's the way it always happens. I guess it's the way it happens for the Academy Awards or something. You get this phone call in the middle of the night or something.

And the next wonderful part of the story is that, of course, I called my best friend Jane right away, who had actually written this story after I had told it to her, re-written it, and I said, "Jane, you won't believe this, but someone just called me and they said I had gotten the Caldecott Honor. Do you think that's for real?" (laughs) And she said, "Oh, well, guess what. I just won the Newbery." And that's the equivalent, of course, of the Caldecott. It's the award that you get for writing, and I had gotten the award for illustrating. So it was just such a totally serendipitous and unbelievable story in a way. So I think we went and had tea. We were known for getting together and having tea in the afternoon and it was a lovely thing.