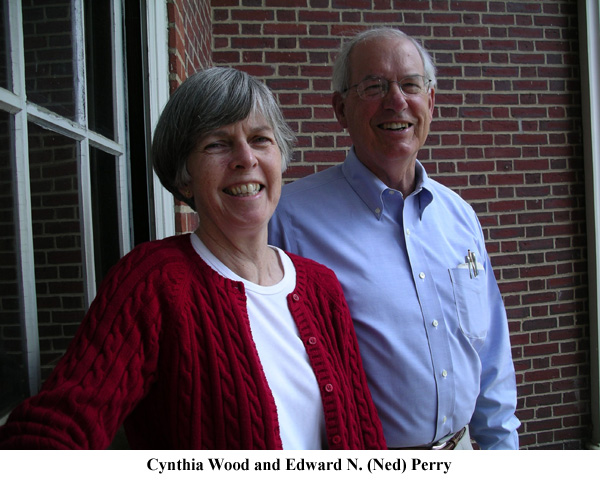

Edward N. (Ned) Perry

Interviewer: Michael Kline

Date: June 5, 2013

Place of Interview: Staff quarters in the lower library in Concord, Mass.

Transcriptionist: Adept Word Management

Click here for audio. Audio file is in .mp3 format.

Michael Nobel Kline: Today is June 5th. We are in the staff quarters in the lower library in Concord, Massachusetts. I am Michael Kline and here with Carrie Kline, interviewing for the Special Collections. Would you say, "My name is," and introduce yourself please?

Michael Nobel Kline: Today is June 5th. We are in the staff quarters in the lower library in Concord, Massachusetts. I am Michael Kline and here with Carrie Kline, interviewing for the Special Collections. Would you say, "My name is," and introduce yourself please?

Edward Needham Perry: My name is Edward Needham Perry and I come from Concord, Massachusetts.

MK: And your date of birth?

EP: My date of birth is October 16, 1946.

MK: Okay, so would you again say "My name is?"

EP: My name is Edward Needham Perry from Concord, Massachusetts and my date of birth is October 16, 1946.

MK: '46. Why don't you start out and tell us about your people and where you were raised.

EP: Well, unlike my wife, I was raised here in Concord, Massachusetts. I moved here when I was 3 days old from the Mount Auburn Hospital in Cambridge, and have lived the majority of my life right here in Concord. My parents moved here from Providence. My mother grew up in Boston, as did my father. I have an older sister and brother who were born in Providence and then I was born in Cambridge, Mass. I have a younger brother and sister and an even younger brother. As I say, I have lived most of my days here in Concord, Massachusetts.

MK: Do you want to talk about the house you lived in, the neighborhood, your family, or some of those things?

EP: We started out on 8 Wood Street, which is in the Y between Elm Street and Main Street, right next to the Concord River. I guess at that point it is the Assabet River. I can remember my father mowing the lawn between the house and the river with a push mower, a push wheel mower that the wheel turned from the activity at the wheels. My mother had golden retrievers and trained goldens in the backyard. We played in that same area between the house and the river. We were fortunate enough to have a school right on Wood Street called Brooks School. My older sister, brother, and I all were able to walk across the street and attend Brooks School before going on to middle school and further education.

MK: Middle school?

EP: Well, middle school would be after the elementary school where we went to Brooks. I went to Alcott School for the 4th grade, which is considered a middle school here in Concord. Actually, that's an elementary school. A middle school is I guess 5, 6, 7. I went to Fenn School in the 5th grade. Fenn School was a private school on Monument Street here. It was a boy's school. My sisters went to Nashoba and then to Concord Academy.

MK: Tell us your recollections of Albright School—.

Carrie N. Kline: Alcott?

MK: Yes, Alcott School. I'm sorry.

EP: Alcott School had been recently built. This would have been in 1956, I think. It was one of the early schools in Concord that had a flat roof. Some people questioned whether flat roofs were good for New England with the snow in the wintertime. It was a single-story, flat roofed school in the shape of a Y, or V, I guess it was. At that time, I believe it went from 1st through 4th or 5th grade. I was there for a year. Fun classmates, all from Concord, still in touch with some of them. Some of them still live here in Concord.

MK: What about the sort of culture of the school? Did you have men teachers, women teachers? Did you go on field trips?

EP: I believe the teachers at Alcott School were mostly women at the time. Over the course of the last 50 years there had been men—good men—male teachers as well as women teachers. Both of our daughters went to Alcott School, so I am familiar with it back when I was there as well as more recent times. I think the first time that I realized the history of our town was when our 4th grade class went on a field trip. We were able to walk, not go by bus, to the Orchard House where Louisa May Alcott wrote. We went by the then called Antiquarian Society, which is now called the Concord Museum. On the same trip, we walked past the Old Manse out on Monument Street to the Old North Bridge and we realized that we were living in a town with a very special history.

MK: You had heard this history through your family but had never--?

EP: Well I don't think—by the 4th grade I am sure I had been to the places with my family, but by the 4th grade you are beginning to learn what history is. The teacher was able to teach us what history was by showing us where history had taken place.

MK: So talk more about your educational development in Concord.

EP: After going to Alcott School for a year, I went to Fenn School, which was started by Roger Fenn, a private school for boys. He believed that a boy's education should very much be part of the environment and a natural education as well as books and learning. I certainly blossomed in that environment where I enjoyed the natural environment of Concord as much as I did, perhaps more than the classroom.

CK: Natural?

EP: Natural history being the natural environment. The streams and the woods, and I loved to run. I would go out on runs through the Concord Woods through the Estabrook Woods. Once in awhile, I had a teacher who would go out there with me and keep me company. I also was growing up and fortunate enough to have a mentor named John Park who was a naturalist who worked at the National Wildlife Sanctuary in between Bedford Street and the Concord River. He had a trapping line. He was trapping muskrat and mink at Spencer Brook which he allowed me to—. Its called running the trapping line, so that he wouldn't have to drive out to that area of town everyday. So I learned about the natural habitat of our local community by being intimately involved in it. Fenn School encouraged that type of learning process outside the classroom.

MK: Were there Thoreau diaries? Did they become texts?

EP: Not at that time, but certainly many students in Concord are encouraged to read them.

MK: But they weren't part of the school curriculum at Fenn?

EP: Not that I can remember here 20—50 years later.

CK: I'd like to hear about trapping. What animals were entrapped by what? What were their natures?

EP: Well at that time, the clamp leg traps were still allowed and I was—. John Park taught me how to set them near deep water. One of the difficulties with leg traps is that animals can—. If they are in a trap a long time and they don't die, they are thought to suffer for a long time. If you trap the animal in deep water, it's more likely—or near deep water--it's more likely for them to die relatively quickly. We did that and because I ran the line every 24 hours an animal was never in a trap for longer than that. Most times the animal—. I would find an animal dead in the water. The animals were from muskrat to mink to raccoons. Raccoons were a little more troublesome than mink and muskrat because they sometimes would be able to avoid the deep water and—. But you set the trap where you would be expecting a mink and a muskrat and not a raccoon to come by. So that's what we caught mostly. You would look for paths along the brook banks where animals were slithering into the water. That's where you would learn to read the streambed and the stream banks to know where the animals were going.

CK: You said read?

EP: Read it like reading a book you would read the forest, read the brook banks. There are all sorts of ways of reading in our natural environment.

MK: Was this trapping done in an effort to control overpopulated species or did he have other reasons for the trapping?

EP: The trapping was done for pelts. We would skin the animal and the skins would be sent to New York for curing and use.

MK: That's great. More about your—. I am interested in the development of the ideas that sort of guided your life.

CK: We haven't heard a whole lot about your parents. Maybe they played a role in that or—. We know that Dad ran a push mower.

EP: Well my father was a stockbroker. My mother was a horseback rider and dog trainer. Both great parents, very family oriented. We always had dinner together at the dinner table. My father would come back from Boston on the train, sit down at the dinner table, and ask each one of us what we had done during the day. Oftentimes my mother would have asked us that question before so oftentimes my mother would pipe up and not let us answer. "Oh Ned did this or did that." So we all got used to having my mother speak for us. It was certainly a family unit. My mother became involved with the 4-H and the Pony Club in Concord, which is all to do with horses and then started something called the Old North Bridge Hounds, which was a hunt club. My father and I never rode horses for one reason or another. I had always found it uncomfortable and found the tractor to be more reliable. My father and I ended up parking a lot of cars in parking lots during horse shows or Pony Club events, and that's just the way we found as a family to work that we all did things together pretty much. Concord was a great environment for it because of the openness and the open space of Concord. The horses had—. Horses and their riders had lots of trails to ride on. Also, there were lots of hay fields to be mowed and hay baled for the horses during the wintertime.

MK: So this must have been a real passion for your mother.

EP: Horses were certainly a passion for my mother. She was also an artist and did some sculpting and some wood block cutting. A lot of the time the topics were horses or dogs, particularly goldens. There was a woman in Carlisle named Pagey Elliot who wrote books about goldens and my mother was asked to illustrate some of those, and she did. She was a good artist, as well as a good mother.

MK: Is she still living?

EP: No, she died in 2004 and my father died in 2007.

MK: So we're getting there, trying to picture you now in your pre-college years moving toward developing your intellectual and other skills, but I've to get you to the moderator place now. You will have to—.

EP: It's a fairly easy transition. In Fenn School, I had two friends named Bill and Sam Newbury and we rode to school together. Their father was Bert Newbury. And Bert Newbury, I learned from my father, was the town moderator. My father and my mother both served on many committees in town but my father served when I was at Fenn on something called the Retirement Board, using his investment skills. The Retirement Board oversaw the retirement funds of the employees of the town. One Saturday my father disappeared off to a meeting and at lunchtime that Saturday, I can remember asking him where he had been. He said, "Oh, I went off to a meeting, preparing for a town meeting." "Oh really? What was that about?" He said, "Well, it was at Bert Newbury's house. We went over the agenda for town meeting." And I said, "What does Bert Newbury's house have to do with it?" He said, "Well, Bert Newbury is the moderator." "Well, what does the moderator do?" Dad said, "Well, he sort of pulls people together and moderates town meeting." I either thought to myself or expressed the idea that that's an interesting position.

My parents were both very loyal town meeting-goers. Concord is run by an open town meeting as compared to a representative town meeting. About 47 towns in Massachusetts are representative town meetings where people are elected to be a town meeting member. The rest of the towns in Massachusetts are largely run by open town meetings where all citizens can walk in and express their opinions and vote. My parents did that. In fact, I have some pictures of them going into the Concord Armory. It must have been early in the 1950s. Town meeting in New England for decades, if not centuries, was a social gathering in the Spring. The women would dress up and the men would dress up. It was sort of a rite of passage into the Spring and Summertime where people would come out from their houses from the cold winter weather and come and talk about the future of the town. Clearly, that's what my parents were doing in these pictures from the 1950s.

We would talk about town meeting at the dinner table. We all were trained to be public participants in one way or another. When I became old enough to vote, I started going to town meeting. I was probably one of the few people in Massachusetts who took a date to town meeting. There was a woman from New York who wanted to see a town meeting and I said, "Well sure, let's have a date and come to town meeting." So she sat on the visitor's section. I think I sat there part of the time and then when it came to vote you would move out of the visitor's section and vote and then come back. I am one of the few people, as I say, that has probably taken a date to a big, public town meeting. It was an education for her. She's moved on to be a good public administrator. Maybe it had some impact on her.

MK: Anybody who would take a date to a town meeting must certainly remember his first town meeting.

EP: Well I have lots of stories about first town meetings but I am not sure which was the first one.

MK: Well try a few of them and maybe we can—.

EP: Well I think the date is an early one. We had a town manager who was very proud to have worked his way up to be town manager of Concord. The Board of Selectmen asked him to handle the warrant article.

CK: The what?

EP: A warrant article. The agenda for a town meeting is called a warrant and there are articles 1-50 or 1-72, however many articles there are in the warrant. And those were all handled by the proponent of the article, whether it be a town committee, a citizen petitioner, or some other enterprise. The majority of the town-sponsored articles come from the board of selectmen. The board of selectmen introduce the article to the town meeting. Ted Nelson was asked in his first year to handle this article. So he squared his shoulders and says, "This is an honor and I am glad they recognize the fact that I am a capable administrator. I will be glad to do that." What it happened to be was changing the parking setup on our Mill Dam, which is our main street through town from slanted parking to parallel parking. Ted Nelson stood up and gave a great presentation. The moderator says are there any questions. There wasn't a question in the house. I mean, there are 300 or 350 people out there and not a question. So Ted said, "Great presentation! I must have answered all those questions," and he sat down. The moderator asked for a vote all those in favor and about three hands went up. All those opposed, and 347 hands went up. The article was defeated. Ted realized that the board of selectmen understood that this concept was not going to go over well in town and so none of the selectmen wanted to handle the article and be defeated, be seen as being defeated. So they handed it to Ted. Ted said that was a pretty good education in itself. As I say, I could go on for a long time with stories about town meetings but that's one of them.

MK: Please do, please do. At least 2 or 3 more.

EP: That would be—that—.

MK: That's a great one. The reason I want you to explore it further is that this whole idea of the town meeting is certainly an enigma to us coming from West Virginia and I think to most parts of the country. We just have no experience in this level of democracy and so that's why it fires my imagination to hear you talk about it. If you want to tell a couple more—

CK: These stories really help, whether they are from the early years or your years or in between.

EP: I am interested that you use the word enigma. Town meeting came out of the Celts in England, and the British actually had village meetings. They came across the ocean and New England started using the town meetings well before the Revolutionary War. It was a Concord town meeting that empowered some of our representatives to go support the dumping of the tea in Boston Harbor. There are records of Concord town meetings really going way back to the start of Concord. The original ones were church records because that's where the meetings would be held. I have used some of the statements from those early records in my term as moderator. I have actually used the oral history collection of the Concord Library to go back and listen to narrators talking about town meeting issues to help me moderate those issues in subsequent meetings.

Annabel Kellogg, for instance, one of the narrators of the oral history tape. She came up with a concept of extending Baker Avenue off of Main Street, which at the time was going to a fairly large building complex, office building complex and Baker Avenue was putting a lot of traffic onto Main Street in the morning and evening rush hours. She said if we just extend Baker Avenue over to Loop 2, which is one of the main thoroughfares through Concord, all that traffic can go out onto Route 2 instead of onto Main Street. So she brought an article to town meeting and is credited for having this relatively simple idea solve a major traffic problem in town. That's what town meetings are all about and that's what the citizen input is all about. That is one of the beauties of the democratic form of government that the town meeting provides to our New England towns. When we travel across the United States, we hear that people are disenfranchised from their government, and I often wonder why the town meeting form of government didn't travel across our country with the development of governments. Some of the southern concepts must have been contrary to the town meeting forum so it didn't get past New York State.

MK: Western Virginia had fewer English people in it. They tended to stay closer to the seaboard and the more tillable land. There were a lot of Scots-Irish and German people who came. There's very little—. I mean we have town councils, which is a kind of representative town meeting I guess you could categorize it that way. An open town meeting with all the traditions of how you bring things before it and how you discuss it and how it's moderated, we don't know about that. It's a stranger to us.

EP: It's a really good form of government.

CK: Let's pause for a minute.

MK: So this open meeting has deep roots in Concord?

EP: Very deep roots, and hopefully it will go on for many years. There are lots of different parts of town that have been created by the citizens. In addition to the Baker Avenue extension, in that same area of town there was a street called Assabet Avenue, which probably had 15 or 20 houses on it and young children in the families. The school bus would both have to go to Assabet Avenue on Route 2, a busy high speed road, as well as coming back out onto Route 2 coming out of Assabet Avenue. As Route 2 became more of a high-speed highway, state highway, some of the citizens thought that it would be better if the Assabet Avenue could be re-transfigured so that it went out on Barrett's Mill Road rather than dumped out on Route 2. The citizen came to me with the idea and I as town moderator guided him to the public works commission, police department, fire department, and the school committee, all of whom had ideas about how the road should be changed. Eventually he came back to town meeting with the support of all these groups with a warrant article to change the street so that it didn't dump out on Route 2 anymore, but came off Barrett's Mill Road. We moved it through town meeting and the citizens were very happy that they have a much quieter neighborhood and a much safer neighborhood for the school buses to go in and out of. All because of the citizens coming up with an idea and pushing it through this town meeting process.

Could that work through a city counsel? Could that work through a state legislature? Sure. There are lots of different ways. In Concord's open town meeting process, the citizen can collect 10 signatures on a petition to put an article on the warrant every Spring. There is also something called the special town meeting where citizens can themselves ask for a special town meeting. That would take 100 signatures on a petition article to get an article on a special town meeting. Those can be held anytime during the year. We are required by—.

MK: You have moderated some of those?

EP: I have moderated special town meetings as well as annual town meetings. Some people know me as a town meeting junkie because as I—. Shortly after becoming town moderator I was asked to join the Massachusetts Moderators Association and became involved with the administration of that organization and eventually became president of that organization. I have probably gone to 50 other towns to watch their town meetings, help the town moderator through difficult issues, or just provide him or her feedback on their moderator style.

The special town meetings that I recall, I was fortunate to have an early one in my tenure. It must have been 2001, or could have even been 2000 when the town was buying a property, which was owned by the Benson family. The Benson family either had gotten the land from the King 300 years ago or was the second family to own it. They were very private brothers who had ended up owning this. One I think had died and the other one I think had moved to Maine. The town was interested in buying the land for future water sources. Concord, I think, has six or seven different wells, or water sources. The Benson property is near the Concord River and was thought to be a good future source, not that we needed the water right away. The Concord government and the board of selectmen are both known for being forward thinking and forward planners and looking ahead. The board of selectmen brought a warrant article to this special town meeting to buy this land. What I remember about that town meeting was that the Benson brother who was still alive, I was told, would come down from Maine and want to speak.

Well, in town meetings in Massachusetts, generally, only citizens who are registered voters are allowed to speak at town meetings, or the moderator gets permission of the town meeting for outsiders to speak. But in Concord's town meeting, we do that very rarely because we think the town government and the town should be run by the citizens. I was told Mr. Benson, I was told, wanted to speak and would approach the microphone. Then the town clerk and I had an agreement that we would let him do this without interrupting the flow of town meeting by asking permission because this family had owned this land for so long.

This bearded, gruff looking gentleman, it was clear to me who he was when he was approaching the microphone. I said I would like to go to microphone number 4. He was up there and the mike was turned on and he spoke probably about 10 minutes about the—. Ordinarily the moderator in Concord at this time was allowing people to speak for 5 minutes. I subsequently shortened that to 3 minutes, but Mr Benson spoke from the microphone for 10 or 12 minutes. You could hear a pin drop in the hall. People were so tuned in to what he had to say about his family, love for the property, and how it had come down through the generations. They were thrilled that the town was buying this so that it would be preserved in perpetuity for the future generations of Concordians to walk on but also to get the water from the wells that someday would be drilled in it. That's one of the special town meetings.

Another special town meeting was on an issue with playing fields, synthetic playing fields at the high school. In the annual town meeting, we had had a long and somewhat contentious debate by different groups in town. A vote had been taken. A very unusual procedure of a motion to reconsider had been made. I had made a ruling on the motion to reconsider that allowed the issue to be reconsidered. The vote was subsequently reversed. The original vote was subsequently reversed, allowing the schools to build the 2 playing fields on an area where some people in town considered it to be "Henry David Thoreau's Woods." When I was growing up, some of that same territory had been the town dump so I knew that Henry David hadn't walked over the land where they wanted to play—that was some of the playing fields. So anyway, the vote was reversed late in the evening and there were a lot of citizens in town who were upset by the vote and probably upset by the moderator.

They asked for a special town meeting. The special town meeting took place at the end of June and we had the largest town meeting. I think the largest town meeting that Concord has ever had, which was about 1,800 voters coming out. The moderator is responsible for making sure that everybody is connected by, at least voice so that everybody at a meeting can hear the speaker and can react. In Concord's town meeting, we actually try to connect people visually also. We have television cameras and screens in as many rooms as we can. That meeting—. We ordinarily have town meeting in the auditorium and in the cafeteria at the high school. When we are expecting a large town meeting, we also set up the gymnasium, which gets us to about 1,400 people. That night I actually had classrooms also set up with sound and we went into at least two additional classrooms, maybe three to house everybody. The meeting went exceptionally well. The speakers were as eloquent as my wife has previously said. A vote was taken mid-evening, which supported the playing fields being built.

There were three or four subsequent articles on the warrant that were sort of contingent on that vote. All the petitioners of the subsequent articles withdrew their motions for those petitions, so the meeting came to a relatively early evening end, by 10:00 or 10:30. Luckily, the feeling going out of that town meeting was that the town had met, we had all come together, we had discussed the issues very civilly, the town had made a decision, and we would go forward. That's what happened. It was fun to be part of it. So that's what town meetings are like. There are so many different aspects of town meeting, but it is a wonderful form of government. I think the open town meeting process allows every citizen, from all walks of life, from all forms of education, equal right and access to ideas and to the government of his or her town. I hope that it will continue for many years in Concord.

MK: Well, this is a fantastic testimonial. I wonder if through your association with other moderators if you know of anybody else with your level of passion for this whole process. Someone who would go back and listen to an oral history interview of a previous moderator to try and learn more about the traditions of moderating and the—. I just think it's remarkable level of interest that you have in all this.

CK: The commitment.

MK: It probably played a very big role during that period for keeping the focus where it needed to be because you were so focused yourself. Do you know of other people who have pursued it at the levels that you have?

EP: I—

MK: Has anyone written about it?

EP: I have been written about.

MK: Have you written some of these ideas you have just told us in this interview, about the importance of it?

EP: I actually developed a CD, a DVD, on the town meeting form of government for the Mass. Moderators Association. Your predecessor Renee Gerrelick, who did so many oral histories, I was extremely pleased to have her participate in it, because I captured her and her love for town meeting shortly before she died. I just felt that she had preserved so many stories about Concord in her oral history that I was honored to have her participate in this DVD. To the development of that, we had—I guess—five moderators, talking heads, interviewed, and professionally filmed. We understood having watched the draft of that tape if you will that no one would get past the first moderator if anybody even attempted to watch it. We then got a professional broadcaster to come and narrate the DVD, the stories about town meeting by the different moderators. We interspersed him and let him do the lead in and fade to the next moderator. That improved it thirty to forty percent, but we said we are really missing something here. So we asked three or four voters from each of the towns where the five moderators came from to come to Concord's town house and be interviewed and talk about their passion for town meeting. And Renee was one of them, as I have mentioned. The DVD was a hundred percent improved by having the citizens' input and it livened it up a lot. It was actually a popular DVD in Massachusetts for at least a day, maybe three.

(All laugh)

EP: It's available in the library here. The idea was to use it as an educational tool for introducing citizens to their town meetings.

MK: So Special Collections knows all about this and the raw footage for it?

EP: No, the raw footage never got—. This was a Mass. Moderator's project, not a Concord project so it was done by the Mass. Moderators.

MK: But you were in it so it would qualify.

EP: I don't even know if the DVD is still in the library. I don't think the DVD was in Special Collections. I think it was available to the public on a shelf about town meeting. Mass. Moderators Association puts together a book called Town Meeting Time, which is the rules and regulations for open town meeting and representative town meeting. Each town's library in Massachusetts generally has a section about town meeting and I think that's where the DVD would be if it still were here. I have copies if you ever were interested in seeing a copy or having a copy.

CK: Yes.

MK: By all means, we would be interested. I wonder if the local school boards wouldn't want to consider it as a part of their civics.

EP: We would hope that they would. There is a class in Concord at one of the middle schools that does a town meeting section as part of their curriculum, and the students are given different roles for town meeting. I went to a daycare center to try to talk about town meetings so that the kids would go back to their parents and say, "What is there about town meetings that I should know?" I had a choice between a cookie and a bowl of ice cream as to what the kids would vote for. The next day one of the daycare center administrators said that one of the students came in and said, "How come the moderator gave us an unhealthy choice?" I am not sure which was the unhealthy choice but it may have been the ice cream. (laughs) You can get into trouble doing all sorts of things, but do try to teach kids about town meeting in the Concord schools. There are lots of different ways of doing it.

MK: Well, that was a very informative view on being a moderator the town meeting. Did you have your own practice and so on that—?

EP: Oh yes. The town moderator is only a volunteer job. It's unpaid. My profession is an employment relations lawyer, trying to keep people working together and the subspecialty of that was glass-ceiling work where I tried to make sure that women were treated as well as men in the employment world. I started out with the U.S. Department of Labor in 1975 and went through 1982. I was fortunate enough to be in the right place at the right time when people came looking for people to do things. I ended up with two or three Solicitor Labor Awards for the work that I did. I came up to Boston in 1982 and worked with several different law firms in the employment relations world, always trying to make sure that discussions between employees and employers were conducted civilly and productively for both the organization as well as the individual.

I enjoyed that practice and was blessed to have a terrific supportive wife and two wonderful daughters, both of whom have followed their mother rather than their father on in their professions. Our oldest daughter is a physician's assistant down in Atlanta. Our younger daughter is working on a PhD in physics at Harvard in her 4th or 5th year. We think we've—. I know I've been blessed with a great family. The practice enabled me to both support the family, as well as having partners who allowed me to do volunteer work both for the town of Concord and as well as being on a number of different boards and committees. There were two long ones. I was a trustee at Mount Hermon School, which is out on the Connecticut River for 18 years. I guess I have now been a director of a public company for 22 years, so I guess two longstanding boards have kept me around for awhile.

MK: Sounds like it.

EP: I have been—. I've had a wonderful professional career. I retired as of December 2012, and someone asked me last night how retirement was going. He referenced that one of my other partners who has retired said, "Now I am just beginning to live." I don't feel that. I have been living for a long time and I certainly am enjoying the opportunity to do more for the community in which I live. I have been on town committees both up in Harpswell, Maine where we have a second house, as well as having just been asked to be part of a town government study committee here in Concord. It's sort of a fast-track committee focused on how town government could be improved beyond what it is. Two days ago, I sat in this library and we discussed how the Library Committee along with the Library Board of Trustees as well as the Friends of the Library provide services to the citizens, and whether that process could be improved. Citizens are continuing to look at the Concord government and see if services can be provided in a different way or in a better way. It's all about citizen involvement.

MK: Did you at some point study mediation or do you have to be a natural mediator to be a good moderator? Because you were doing a lot of mediation between employees and employers. Did that just come naturally to you? Because there are study groups on that now and people who really try to learn mediation. You took a—. Carrie took a mediation course at one point. Is that part of your background?

EP: Moderators in Massachusetts come from all professions. Close to the majority of them have been attorneys that I know of through the Mass. Moderators Association. In addition to needing to be an okay mediator, I think a moderator's greatest skill is the ability to listen. I think it's probably a necessary skill for a mediator also. But to be a good moderator in the Massachusetts town meeting process, you really need to know the citizens who make up your town. You need to listen to citizens in addition to the boards and committees in the town so that you are able to bring people together. As moderator, I would meet with people on all sides of any issue separately to try and make sure that their presentations were as good as possible so that the citizens in the town meeting would understand their perspective, irregardless of where my personal opinion was on any particular issue. I think it's important for a moderator not to display personal biases in any respect as they are moderating a town meeting.

Early in my moderatorship, I was trying to compliment people when they made a good presentation during the town meeting. Sometimes I would compliment people even if I didn't agree with their position, but I wasn't consistent in my complimenting and people thought that I was showing a bias by complimenting people's presentations. So I stopped that practice during town meeting but I would write notes after the town meeting thanking them for their presentation. It's just a sort of little fine-tuning that you learn through the process of being a moderator. That's the type of thing that I needed to listen to, have someone comment to me, and then say, "Oh yeah! I understand that. That's showing a bias or could be seen as showing a bias."

I also had four people at a coffee shop in town. I didn't know the four people but after a town meeting session I would go by them and say, "How did I do?" They would be very candid with how I had done early on. In later years now that I have stepped down, a couple of them have approached me and said, "That was a really great idea for you to come by. We didn't know you. You didn't know us but we were more than glad to help you become a better moderator. You were a good moderator for doing that." It's a process and I think you need to be a good listener to be a good moderator.

CK: So you would just walk into a coffee shop, and ask the general—?

EP: I recognized these four men as people who were long time town meeting goers. I knew they were part of the process, but I was at, I was learning. Every moderator—. It's very hard to step up to a podium and be a great moderator from the start. Every moderator starts—. And these four men were more than willing to comment on what I was doing. One day one of them said, "You know, you really cut that person off inappropriately. You should apologize." I went and apologized to that person, because if that was the perception in the town meeting that the moderator had been unfair—. I eventually started putting a clock on the screen so that everyone in the meeting would know how much time the speaker had. The first time limit was probably four minutes, maybe three minutes. The first speaker that went up against the clock was a chairman of the board of selectmen. When the bell rang, I said, "You're through." The chairman looked up at me and said, "If I had known you were going to be serious, I would have asked for more time." I said, "I am sorry. You didn't so we are through." She had to sit down. It was--. Without being staged, it was a good message to the town meeting that that clock meant business and the moderator meant business with the clock. People—This was a fairly inovative thing in Massachusetts and a number of towns now have the same clock up on the screen.

I asked a scientist in town named Cline Frasier to find me a clock that could go on the screen. He had been with NASA and had helped put people on the moon so I figured he could find a clock for the screen. He came back and he said, "I have three versions. I have an expensive one at $28.50. I have a cheap one at $18.50, or you can get a moderate priced one at $22.00." I said, "Well, let's go with the $22.00." That's what has worked for the town. I don't know if that version is still used but it was a wonderful solution to an issue where the moderator can be seen as being pretty harsh if you gavel a speaker closed at the end of their time, particularly if the town meeting wants that speaker to keep speaking, if they want to hear from that speaker. But by putting the time frame in and encouraging speakers to practice their talks before the mirror at home before they come to town meeting, we actually think it has improved the quality even further than it was originally. The present moderator I think for some of the articles actually has moved the time down to two minutes on the clock. I think you can barely clear your throat in two minutes but it works.

CK: You did three?

EP: I probably started at four and I may have reduced it to three. Sometimes, you know, a lot of people want to speak about an article and so you try to get as many people—. My position was you try and get as many people to the microphone and speaking to their fellow citizens as possible. Sometimes you know that, like the special town meeting about the buying of the Benson land for water, which was largely a one-article evening so you know that Mr Benson—. You can allow him to go on for 10 minutes. No noise in the hall so everybody is paying attention. No one is restless. A moderator can—. I am sure you can tell from [the participants] when they are getting uncomfortable and fidgeting. A moderator can take a look at the town meeting and know if people are tired of the speaker and want to move on or have rapt attention and are listening to every word. So special town meetings have fewer articles. You have a little bit more leniency on the time frame. Annual town meetings may have 72 articles and in Concord that means two or three nights of town meeting. The moderator is generally pushing to get things organized so that you have it completed in three nights. If you have to go to a fourth and fifth, that means a second week and that means tearing down the hall, all the electronics, and $7,000 more to set it up the next week. It behooves the town and everybody to be cooperative and get it done in two or three nights and generally, we do.

CK: If you are comparing, I can look at my narrator and you have people in all different rooms. It's a two-way camera and you are catching the vibe of people say throughout the school? Is that how that works? In terms of—

EP: We have cameras in all three of the major halls. So even if it's focused on a speaker at a microphone—the moderator in the auditorium controls who is speaking and when. The auditorium has four microphones in it so the moderator has control over those four mikes, with the electronic specialist who is working these mikes. There are generally two in the cafeteria and one or two in the gymnasium. If the moderator wants to hear from the cafeteria and the people in the cafeteria, of course, it's wise to spread the microphone around so that you hear from all forums. When a person is speaking in the cafeteria the camera is on that person, but you can see the people behind that speaker in the cafeteria. At the same time you are watching the auditorium, the people in the auditorium. So you get a fairly good sense—. A good moderator doing it right gets a fairly good sense—. Also in Concord, the moderator has a phone link with a moderator in the cafeteria and a moderator—. They are assistant moderators in these other rooms. Through that phone link while someone is speaking in front of me and I have one ear towards them, I could also pick up the phone and say, "Carrie, do you have any speakers and what's the attitude over there?" I even sometimes ask procedural questions. The moderator is the ultimate judge and ruler of the town meeting, but if I am unsure of something that's going on, I had no problem asking an assistant moderator, "What did that person say in the cafeteria while I was asking a question in the auditorium?"

So it's very fluid. You have to be quick on your feet. You have to carry the persona of a moderator. I have seen a number of town meetings get way out of control because the moderator loses the control of the meeting and the citizens. And so you have to be fair and equitable to all the speakers. Citizens have to have ultimate trust that you are being fair. I suspect it's similar in Elkins and other communities across the country that we hope our public, collective representatives are listening to everybody.

CK: Is this generally a man's role?

EP: More men have been moderators than women have, but women are very good at moderating. Some of my very best friends in the Mass. Moderators Association are women. I heard from one this morning who sent me an email saying she would like to talk to be about some issues in her town. It's—. I think women are often more detail oriented and better listeners. I think if you are a good listener you can be a good moderator whatever gender you are.

CK: I just asked because I was thinking about your comment on the persona, it's how you are regarded by the crowd too, isn't it?

EP: It is. We had a nurse named Pat Snow who worked her way up in Emerson Hospital, which is the hospital here in town. It's a major employer, the largest employer in town. Pat Snow had a persona that let you know that she was in charge. We had a high school superintendent named Elaine Dicicco who marched into graduation every year at the head of the procession. You knew that Elaine Dicicco was in charge. There are women who can do this as well as men. Some people do it and some people shy away from it. I didn't want to put up my hand the first year of law school class. Some people still wonder—. I believe that I'm a fairly shy, retiring individual. Somehow having watched Bert Newbury, having watched Arthur Stevenson be a moderator of the town, I was able to get up to the podium and carry that persona off well enough so that I was elected. A moderator is elected every year on an annual term. The town can get rid of the moderator and the moderator can say, "I don't want to do it." Concord's moderator generally serves from eight to twelve years. After ten years, I thought that the town probably needed a new face up at the podium so I said that I wasn't going to run again and stepped down.

CK: It sounds extremely stressful.

EP: I think it was as stressful for my wife as it was for me with all the phone calls that we received during the buildup to town meeting.

CK: So much frustration is, I imagine, directed at the person they can see or the name they are familiar with.

EP: I think if the moderator listens and treats everybody equally, there is little frustration focused at the moderator. The best moderators don't want to see their names in the press. You want the town meeting participants to leave the town meeting discussing the issues. Discussing whether that water main should go down Main Street or whether that school should be built over here or whether parking lot should go into Walden Woods or playing fields. You certainly don't want them leaving saying, "Gee, the moderator cut that person off. The moderator didn't allow time. That procedure was a little bit—." So you really want them talking about the issues. If a moderator does the job well, that's what will happen. I hope the majority of the time people left talking about the issues.

MK: Thank you. That's a wonderful explanation.

CK: So inspiring to think we could live in a democracy.

EP: It works. It works, and as I say, I hope it will work in Concord for many years to come. It's a great town. This is a great library. These oral history tapes I think will be—I don't know about mine-- but I think there are many that have a very significant interest to other Concordians on what has gone on in the past in Concord and how we should continue to interact as citizens of Concord. I thank you both for carrying on Renee's tradition of building this oral history library.

MK: It's been a great pleasure and an honor for us.

END OF RECORDING

01:08:29.0 (end of audio)

Back to the Oral History Program Collection page

Back to Finding Aids page

Back to Special Collections page

Home