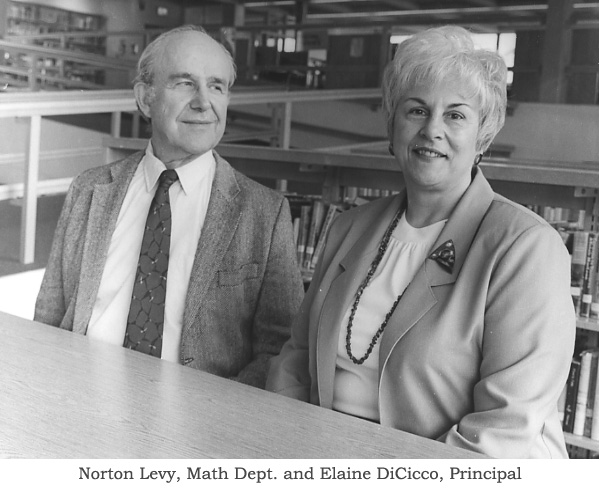

Norton Levy

Math Department, Concord-Carlisle Regional High School

Age: 63

Interviewed May 11, 1990

Concord Oral History Program

Interviewed by Renee Garrelick

Concord-Carlisle Educators Oral History sponsored by Concord-Carlisle Regional High School.

While in the Army, I was wondering what I should do in my future life. I found the

thing that disturbed me with the people that I met from all over the country is that

they had two key deficiencies; their reasoning ability was very limited - they were very

easily misled by advertisements or by people who were trying to persuade them one way or

another politically - and, they did not have the wherewithal to think too clearly

themselves. Through the subject of mathematics, I felt that I could help young people

learn to reason more clearly.

While in the Army, I was wondering what I should do in my future life. I found the

thing that disturbed me with the people that I met from all over the country is that

they had two key deficiencies; their reasoning ability was very limited - they were very

easily misled by advertisements or by people who were trying to persuade them one way or

another politically - and, they did not have the wherewithal to think too clearly

themselves. Through the subject of mathematics, I felt that I could help young people

learn to reason more clearly.

I think of math as being like one of the humanities. There are many questions in math that are not clear cut, that can't be answered as definitely as doing an arithmetic problem. Math is related to almost every other subject in school and almost everything we encounter in our everyday life, and one of the things that I wanted to do was to point up these connections as part of my teaching. In that sense it becomes a cultural experience not just a training in certain mechanical formulas and operations.

Many of the outstanding mathematicians through history were also philosophers, and many of them were concerned about the political turmoil that existed during their lives and some of them tried to do things about this to improve the situation.

I arrived at Concord-Carlisle High School in 1954. At that time, three students were brought over to the high school from the junior high for a kind of enrichment. They didn't have to be bused because the junior high was right next to the high school at that time. Two of those students stayed through high school and did exceptional work while they were in high school. But the third one seemed to be the most aggressive and inquisitive. Unfortunately I wasn't able to continue with that student because she went on to Rose Hawthorne School. Eventually as things turned out, she came back to Concord in a very big way. She came back as a French teacher then administrative assistant and now she is principal of our school and that, of course, is Elaine DiCicco.

The private school drain is a kind of social elitism that exists in Concord as in many other towns, and I feel it personally because what I try to do is to help students stand on their own feet as they go through their educational experience. This pseudo- sophistication as I sense it goes against the democratic principles that students should learn to use their own merits to make their way in this life. Even though they have supports from their parents and the teachers at school, the success or failure of the school and the survival of the school doesn't depend quite so much on how each individual student does, where at a private school, I think, their future might be in jeopardy if they couldn't entice the students to do the work at the level they would like.

I think the schools generally give a preponderance of their special effort to the slow learner, and I've attempted to provide some counterbalance for those with extra ability. These efforts often go well beyond the regular course. They often involve individual projects or individual activities on the part of the students. I have also tried to do a couple of special things that others haven't done for the slow learners. Jerome Bruner, psychologist at Harvard, had the thesis that if you figure out the right strategy, you can teach almost anything to any students. I tried this out a couple of times. At one time, I took a couple of the questions that appeared in the International Mathematical Olympiad, and I went into a so called "average" level ninth grade class and with a certain amount of direction in giving them hints by the end of the class I had the class solving two of the problems that the brighter students in the world had been expected to try. Then another time, I took all the students who had gotten D's or F's in mathematics the previous year and had them all assigned to the same class. For the first month or so of class we didn't have any textbook; we just had puzzles and games and different things which developed a good rapport between myself and the class. Then when I did start with a textbook, there was a much more comfortable attitude and the end result was that every student in the class improved significantly by the end of the year.

The late '50s and early '60s I considered my golden time in my teaching career. I was department chairman, I lived near the school, and I was able to be involved in a number of activities of the community especially in respect to education. I felt that I had a schoolwide influence as department chairman, and I was in the vanguard of change that any ideas that I had would mix in with the ideas of other department chairs or administrators or people in the community, and I felt that I was an integral part of the improvement of the school. One thing that I remember doing was introducing calculus in 1958 and being able to work this into the schedule, first experimentally and then as a regular course.

Although I have been an active member of the teachers' association all through my career, I have felt that the association and the contract that the association has developed every three years has stifled some of the efforts that I've attempted. One illustration of this is their attitude towards the merit program, when we had a merit program in the school. I was a member of the merit committee, and I know how difficult it was to evaluate one teacher versus another, but I felt that it was worth the effort. It did encourage people to do things above the minimal, to think of more creative ways to affect the students in the school. I feel with the contract and with the association there is not the same positive attitude towards the teachers doing extra things beyond what the contract seems to expect, beyond what the administration seems to expect. There has been a long term neglect in encouraging the level of excellence at the school level that I believed in. One small illustration of this is that we don't have any formal advanced placement courses at the school outside of the math department. Even though in some departments they feel that this creates a kind of academic elitism, it seems that they could still apply equal effort to all students and all their individual strengths and weaknesses and still promote the level of excellence that the advanced placement test assumes as many schools do. This is not just a cause that I've pursued; it's an enjoyable effort. It's what revitalizes teaching. It seems when occasionally I hear a student, say going on a math trip with them, saying that they are not challenged that much in some of their other courses, it hurts me in two ways. It hurts in the sense that it downgrades the overall view of the school, and it also means that some of the teachers are depriving themselves of the same pleasure that I get. I've felt frustrated through the years that when I've spoken along these lines, my words have often fallen on deaf ears.

There is experimental evidence to indicate that if a student is going to derive benefits in his or her courses that will apply to solving problems and dealing effectively with the applications of those courses in other fields or in their everyday life, some efforts towards clarifying the transfer of these skills and insights beyond the confines of the individual subject have to be realized in the teaching of the course itself. It seems that a school where interdisciplinary learning and activity is encouraged is going to be more successful in aiding the students find this kind of value in their education. The students don't have the wherewithal to transfer knowledge across discipline lines entirely on their own.

There has been a modest amount of activity in working with some members of the science department through the years in this area. I can think of one of the projects that I was involved in in the early '60s where I gathered together some of the resources of the community where people use mathematics in their occupations. I interviewed these people and in some cases got students to work with them on projects or they came into the school and gave talks. As a result, some part time employment came to some of the students with these people. It was very time-consuming. I just couldn't do that and teach my regular courses, but with some of those people now having matured and been away school for many years, I can see the connection between some of the activities they followed years ago and their present occupations.

I have been involved with various enrichment activities with students that have extended outside the classroom. I mentioned the projects. Years ago we had science and math fairs where the students worked on their own on an individual effort which was different than what the rest of the students in the class did. We also have had competitions within our school and between our students in our school and other schools in a number of leagues. This is regionally, statewide and even nationally when the students are competent enough. We had years ago a Ford Foundation grant where we were able to pursue some of these areas with some financial support so teachers were paid for their efforts during the summer. We've had connections with Lincoln Laboratory where a couple of their engineers came into the school and assisted our students over a whole semester, and the culmination of these projects involved students from our school being admitted to Lincoln Laboratory and seeing how they perform some of their activities with computers. It not only involved students from our school but students from five other high schools. We have an Olympiad at the state level and also at the national level which is sort of a comprehensive examination that seeks the outstanding efforts on the part of the student, not just with the quick answer kind of tests that are usually given, but the top-most students are actually asked to develop long arguments with proofs and discussions more akin to what a professional scientist and mathematician would do.

The students are able to see how students in other schools perform. Some of them become friendly with outstanding students in other schools, and there are many examples that that friendship has gone on at the college level and even beyond. Fortunately, some of those students continue to communicate with me so I can find out what they are doing after they leave high school, and sometimes this benefits the activity that we continue to perform at the high school.

I like to see what other schools are doing so I do some teaching at other schools. I like to share some of the things that I have gleaned through my own experience with students elsewhere. It lets me know the students elsewhere and the teachers, the schools and their program. I think this develops a community of teachers that's extended into professional associations, in my case in mathematics and also in the advanced placement that I mentioned before. We have an Advanced Placement Association of Teachers that's been functioning for 30 years now where high school and college teachers communicate with each other. We have guest speakers, we talk about some of the problems of introducing college level mathematics in the high school level, different options that are explored in this area, and we develop a fairly comfortable coordination between the high school program and the college program.

In 1958 the government developed a program which prepared new curriculum materials that leading mathematicians felt would be more useful in terms of student learning for the contemporary mathematic and scientific needs. They set up training programs for teachers, and I was involved in one of those at the 12th grade level where groups of teachers got together weekly with a university professor and were given more insight into the mathematics. After this training program, the teachers involved found it quite comfortable to modify what they had done before and incorporate the so called new mathematics, and it worked out very successfully and eventually the new materials were incorporated into new textbooks. However, on the national level when this was given favorable publicity, some schools and some states tried to get on the bandwagon without the kind of training I had and my colleagues had, and as a result they were asked to teach mathematics that they didn't fully understand and the students did not do as well in college boards, were not as well prepared in college because they were given mathematics that was sort of forced down their throats by people that didn't quite understand its justification. That's why we hear of stories about some cities and states that banned the so called new mathematics where schools that did have the right training for their teachers were able to adopt it very effectively. In fact, some of the material we even do today is very closely related to the new material that was developed in the SMSG program in the late '50s and early '60s. SMSG technically stands for School Mathematics Study Group but we have an offhand euphemism for it that is "some math and some garbage."

This year the high school team won the state meet in the medium-sized school division; in fact we've won it for the last three years. With the middle school team that I was asked to coach this year for the first time, we competed against 53 other middle schools in Massachusetts and came out highest in the Math Counts competition which is given in all 50 states, and for that reason I was invited to be the coach of the Massachusetts contingent which will consist of the top four students. One of the four is from Concord, the other three from other schools. We will be competing against the top four students from all 49 other states in Washington on May 18. It's been arranged through Senator Kennedy's office that we will be visiting the White House as part of our visit to Washington.

Most teachers when they get a sabbatical go away for R&R, rest and recuperation, by doing things that have very little or nothing to do with education. I thought I would try something that I've been wanting to do for a long time. and I received a half-year sabbatical, and I asked and was given the sabbatical where my year was split down the middle vertically, in the sense that I taught half time at the high school and had half of the day released. During that time I went to the elementary schools and worked with students and teachers on a variety of enrichment topics, and some of those experiences were progressive in the sense that I was invited to a class, and then I would do some things they were continuing and then I would go back again. With one class especially this continued for the whole year. Some of the students then continued afterwards. Their following year some sixth graders were bused up to the high school, which was very nice because the school provided transportation for them each day, three of them for one year and two of them for two years. In that way I could continue with the enrichment that they had received during my sabbatical in 1982-83. I was able to write four articles from the experience we had. In fact that sixth grade class that I visited a number of times, that group wrote a little booklet at the end of the year and gave me a copy of it.

In discussing my program with John Callahan, our department chairman last year who also happened to be on the negotiating committee, it became evident that I wasn't ready to retire completely and the needs of the department were such that they could still tolerate me another year anyway. We worked out a proposal, and it eventually appeared in the contract where I was invited back on a part time basis (called an "emeritus" status) and this year I teach formally just one course, the calculus course. It was agreed while I was here to teach that I might as well continue coaching the math team at the high school level, and when people became aware of my status in the administration in the middle school, I was also invited to coach the middle school team. That way I was able to coach both the high school and middle school team, and we won the honors that I mentioned before.

I feel the important thing is to treat young people as growing between childhood and adulthood whether they be boys or girls, and I try to treat them all equally. There has never been a problem that I've sensed between whether a math student is a boy or a girl. They definitely can achieve success equally; there is no sexual difference that way. When we had our first math team, it was about half girls and half boys, and our most recent math team was half girls and half boys. It isn't that way every year, but it just happens where the ability happens to reside. In fact the other extreme, in my calculus class this year, seven of the eight top students happen to be girls.

Focusing on Concord within the community, there has been some transfer of leadership as it applies to education over the last 30 years. I think 30 years ago the leadership viewed the cultivating of the development of the student from an educational standpoint as an end in itself. And more recently there is a little more evidence that education is a vehicle to advancement economically and socially. This perhaps is tied in with what we're well aware in terms of the breakup of the family. There isn't the degree of the family orientation of life with the growing youngsters; there isn't the same degree of family security. I think part of the explanation in my own mind about why students are sent to private schools is the commitment of parenting. By sending them off to private school they don't give the children and they don't give the family the chance to strengthen itself from the experience of dealing with the difficult problems of adolescence.

I think the marvelous thing in the public school is the benefit students get from a greater exposure to a range of people in society. The youngsters have the same opportunity to develop leadership, but they also rub shoulders with all types of other people growing up. If they're going to be leaders, they are more attuned to the entire spectrum of humanity in society. My own feeling is, and Doris Kearns Goodwin might disagree with me, I don't think Kennedy would have been president or as effective a president if he hadn't had the experience of being in the military where he met the entire spectrum of society, and perhaps the same thing might be true of President Bush.

Each year I still get a psychological high by becoming enthusiastic in a real sense as I have to deal with each new challenge. The kinds of questions the students have - not just the deficiencies they have but the insights that they have - are different each year even from the same age group. I feel it is a personal obligation to be a representative of the whole educational community in tying the adult world, the experienced world, in with these people who are becoming full citizens, becoming knowledgeable people, and I have to be the explainer or the one who encourages them to clear their own thinking in both a logical way and at times in a comprehensive way by relating what I'm teaching to what's most meaningful in their lives.

I had a formal retirement party last June even though I'm not fully retired, and that party was not the traditional retirement party; I designed it the way I wanted it. The usual way where people come and honor the person retiring seemed very passive; it's almost like a birthday, the person who has a birthday instead of that person being honored should honor those who made his life so worthwhile. I wanted to do the same thing in respect to the students that had made my career so rich. So I contacted many students that were all over the place that I had remembered who had impressed me through the years. I was able to have over a hundred of them and a number of colleagues come together from all parts of the country - in fact, some of them were outside the country - at the local rod and gun club. These were mainly people who had made their own way because of their own merits, their own motivation. In a sense it was a realization of what I was trying to do while they were students of mine. I expected too much; my planning wasn't good enough in that I wanted to say fine things about all of them and there wasn't enough time. But they gave me a chance to get to one more person who happened to have married and her name ended the alphabet, so they said why don't you pick the last person so the last person in a way epitomized the entire group. When the section of Concord called Conantum was formed after the Second World War, one of the young children there set up her own little newspaper communicating what was going on in that section of the community. When she came up to the high school, I was fortunate enough to have her, and she was very creative, made all sorts of discoveries. Once when she went out to Chicago for a summer program between her sophomore and junior years and was the top one of the program, they offered her a chance to stay there as a regular student at Chicago, she said "No, I have to go back. I haven't yet rung Mr. Levy dry." One of my great all time compliments! Her name was Joan Levinson, and after all these years when she and I came eye to eye with all the talking a teacher does and all the talking I've done now, we started speaking, and we both broke up. The words were beyond us, so we just hugged. It was just something that probably transcends anything you can describe logically about the nature of the relationship between teachers and students and probably what makes the teaching profession so meaningful in a person's life.

There were over a hundred students, and I think the effort some of them put into getting there also was a tremendous compliment to the fact that they were my students and we had developed a nice rapport, and the memories were good. Peter Webb, who is a businessman in California, managed to take a detour to his parents 50th anniversary in Wyoming by going from California to Wyoming by way of Concord. Marshall Chin who was visiting China came back a little faster than he had planned just to get to the reunion in time. Bob Paul, an anthropology professor at Emory University, managed to postpone the start of his summer program to get to the banquet. Fay Thomas was able to get someone else to cover for her at the college she teaches at for their graduation and was able to get here. Jamie Carbonelle a distinguished person in the community of computers and artificial intelligence was giving a talk the same day in Tennessee; he pushed his part of the schedule up earlier even though not as many people were able to attend in order to catch a flight from Tennessee up to the Boston area. Chris Billings who was living comfortably in the southern part of The Netherlands managed to gather all his financial resources to pay for a flight over to this country to attend. The most significant example I think came from Margaret Frerking who had trained to be an astronaut, had a PhD. in astrophysics, hadn't quite made the astronaut program although she was working on the effort at a company in California; she managed to make it from California alone even though she was seven months pregnant.

One often thinks of idealism as being the activity that goes on in an ivory tower, but I think when you can realize some of your ideals during your career, then the real world isn't that far divorced from the world of our dreams and hopes and ideals. I used to feel, and I suppose this has been an ongoing bit of my philosophy that of every twelve ideas I had, I could realize some progress in half of them, this was a good balance between living with one's head in the clouds while one's feet are tied down in the mud of reality.