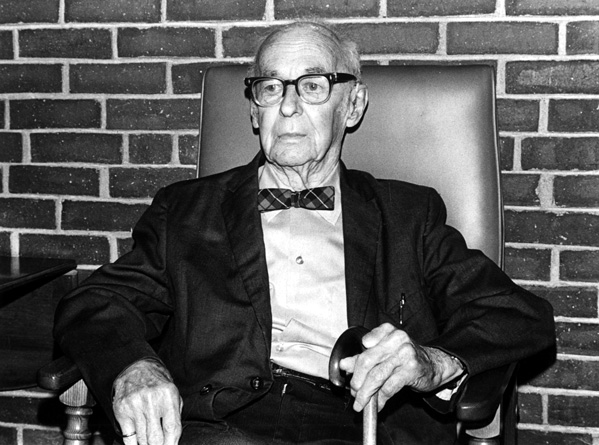

Elmer Joslin

20 Bow Street

Age: 86

Interviewed September 28, 1977

Concord Oral History Program

Interviewed by Renee Garrelick.

The primary responsibility of Concord roads was in the hands

of three road commissioners. At that time the department, which

is now the Department of Public Works, was called the Department

of Roads and Bridges. I was appointed by the road commissioner

and the superintendent of streets and my salary was set by them.

We had charge of all roads excepting parts of Lexington Road,

Main Street and Elm Street, those parts being state highways. We

had charge of all the bridges in town excepting the Elm Street

bridge, which was a state highway bridge. We also had charge of

all playgrounds and parks including the Minuteman and other small

areas which were not considered state highways.

The primary responsibility of Concord roads was in the hands

of three road commissioners. At that time the department, which

is now the Department of Public Works, was called the Department

of Roads and Bridges. I was appointed by the road commissioner

and the superintendent of streets and my salary was set by them.

We had charge of all roads excepting parts of Lexington Road,

Main Street and Elm Street, those parts being state highways. We

had charge of all the bridges in town excepting the Elm Street

bridge, which was a state highway bridge. We also had charge of

all playgrounds and parks including the Minuteman and other small

areas which were not considered state highways.

I first started with the Department of Roads and Bridges in 1916 as assistant to the superintendent. All the roads in Concord at that time were gravel except parts of Main Street and one or two other main arteries. They were called at that time water-bound macadam. Of course, at that time all traffic was horse-drawn buggies or wagons with steel-rimmed tires. Very few automobiles were in existence at that time.

We watered the gravel roads with a watering cart mainly in the two town centers, Concord and West Concord. The watering cart held about 700 gallons of water with two sprinklers at the rear of the cart. This was simply a dust-laying operation.

The difficulty came with the automobiles causing the surface of the roads to disintegrate, blowing away in dust. Concord, as well as other towns and including the state, were experimenting with various kinds of dust-laying. We tried everything possible but what would work in one town might not work in another town due to the consistency of the gravel surface. We went to water-bound macadam, which was just a layer three or four inches thick of fresh stone bound with its own natural dust, which formed more or less of a natural cement. But it was not by any manner or means a permanent cure. The fast traffic of the rubber tires on the automobiles pushed that dust out of the crevices of the stone. Gradually a more permanent surface was obtained by using various kinds of oil and asphalt, which developed eventually into the asphalt-bound macadam.

This type of road was built by laying two layers of stone, one about four inches thick bound together with sand and rolled until that formed a hard surface, and then another layer of fresh stone about two inches thick bound with a hot asphalt or hot tar, and finally a smaller half inch stone was spread on that. This form of road was developed by a Scotsman named Macadam. The base was built with sand of either cobblestones about three or four inches in diameter or crushed stone. The cobblestones were given up after it became more difficult to obtain them. Crushed stone is used today for all secondary roads, and more heavily traveled roads like interstate roads are of concrete.

Prior to the building of macadam roads, the oiling of the gravel roads mainly consisted of dragging done by horses and farmers in the various sections of town, who were responsible to a certain extent for the gravel roads in their vicinity. The drag was used in the spring after the frost left the roads and in the fall just before the roads froze. It wasn't a satisfactory proposition but at least it did level off the ruts formed by mud.

Prior to the oiling of roads, calcium chloride crystals were sprayed, which had a great affinity to attract moisture from the air holding the gravel together similar to oiling. It was more effective and lasted somewhat longer.

In the winter when the snow fell, no real attempts were made to plow the roads until 1917 when I bought a steel plow that attached to the front end of a truck. The only trouble was getting traction for the truck's rear tires. Chains hadn't been developed yet. We even tried two trucks, tandem style, in the hope of getting more traction, but that didn't prove to be satisfactory. The only roads we plowed were the main arteries. Prior to 1926 or 1927 most people that owned automobiles put them up on jacks in the fall and left them there for the winter.

Prior to plowing, the same farmers that did the dragging "broke out", as we called it, the roads in their vicinity by putting a 6 x 6 timber just ahead of the rear runners of a two-runner sled with either two or four horses. All this did was break out a path and level the snow, it didn't remove the snow. This was only done when we had a six- or eight-inch snowfall.

As more snow plows were used, they were improved by curling the blade of the plow so that the snow was pushed and slid along the blade to the side of the road.

We had three what you might call major storms. In 1921 we had a series of rain and freezing forming ice on trees and bushes knocking down branches and whole trees blocking roads. When the trees came down, wires came down as well. As I remember, I think there were three or four days when the entire town or a large part of the town was without electricity.

In March of 1936, we had a period of heavy rain lasting nearly a week causing severe flooding not only in Concord but all over the area washing away houses and bridges. We didn't lose any bridges but we did have one wooden bridge on Pine Street that we thought was going to go with the advancing water.

Then the third catastrophe was the hurricane of 1938 on September 21. It had rained for several days before that day. As the men of the road department were coming in from their jobs, I had a call that a tree had fallen across Pine Street. Just as I hung up from that call, two or three other calls came in. I sent out a foreman and a crew of men to clear the trees which were all in West Concord. At that time, I didn't know and nobody knew that we were having a hurricane. The weather forecasting in those days didn't amount to much, there was no advance information whatever. More and more trees were reported down and the men continued on the job, and about midnight we finally realized we were having a hurricane.

We had at that time a man, who was a cooperative observer for the U.S. Weather Bureau and his wind gauge blew off, went out of commission. The last measure we had was at 125 miles an hour.

We worked all through the night and about 3:00 in the morning on the next night, the selectmen called a meeting at the town hall of all the town departments. We were all working on our own areas and the selectmen felt there should be a single coordinator. After much discussion, I was appointed to coordinate all the departments in the clean up and we all worked well together.

After several serious accidents untangling wires from trees, wires that my men couldn't tell if they were live or not, all power was shut off at the power house. As I would get the word from the manager of the light plant that wires were clear, then we could go to work on the trees. So as fast as we could we opened the streets.

We didn't worry about the tree stumps, we just removed the debris from the trees. Fortunately, we found an old gravel pit, quite deep, at the corner of Sandy Pond Road and the Concord bypass. The owner, a contractor, allowed us to dump all the debris there as we couldn't use our own town dump or we would have filled it up in no time. We had 750 stumps all over town that were removed after the debris was picked up and the streets opened. Some of trees that blew over were leaning against houses, which made the removal of limbs and the tree difficult without damaging the house further. This was particularly true of the Colonial Inn annex, which is now The Wool Shop.

One instance of potential damage done to people was when a section of a metal roof blew off of the area where Snow's Pharmacy is now and went sailing through the air narrowly missing several people including my son.

Many of Concord's beautiful elm trees were damaged in the hurricane including four huge trees on Main Street at the library. Some of them were nearly 48 inches in diameter and they formed an arch across Main Street.

Of course, we didn't have enough tools to clear away all the trees so about 6:00 in the morning after the storm, I called a wholesaler in Boston that I did business with to see if they were in business and they were. And I sent a truck to get two dozen two-man, crosscut saws and six dozen axes, in fact I took all they could spare. We were pretty well equipped then with the crosscut saws. It would take two men about three-quarters of an hour to cut up a tree. Of course, now with the chain saws a tree can be cut up in a much shorter time. I couldn't believe my eyes the first time I saw a man use a chain saw to cut up a tree. When I think how we struggled in those days.

Even though I was born and raised in Concord, I never thought about if I was a Concordian. I asked a friend of mine years ago, whose ancestors helped settle Concord, if he was a Concordian, and his reply was "Lord, no, Elmer, you never know if you're a Concordian or not. You have to be born and die here, so you never know if you are or not."

When I was growing up, Concord was a small town of approximately 6000 population. I suppose it was considered a rural town. Practically everybody knew everybody else. Today you go downtown and you're lucky if you meet one or two people that you actually know. You might recognize their faces but you don't know their names.

In the period of my growing up, it was entirely different. At that time West Concord was known as Concord Junction because it was the junction of the Boston & Maine Railroad and the New York-New Haven Railroad. It was largely a manufacturing town and also had the Massachusetts Reformatory. At that time the Reformatory had about 1000-1500 men there. I think they eventually got that down to about 600.

Concord was a quiet, neighborly town. The trolleys came in about 1899. Electric lights came in about 1898, as I remember it. Streetlights were kerosene lanterns similar to the ones used as railroad lanterns at the present time. A lamplighter came around every morning and cleaned the lamps and filled them with kerosene. He then came back in the late afternoon and lighted them.

Things that we used to do for recreation were coasting, on Nashawtuc Hill for instance, and swimming at Lake Walden and at a swimming hole we had on the Concord River. We had to make our own fun. We did play football and baseball and hockey. We used to play hockey on the various ponds with two rocks as goals. Of course, we had neighborhood gatherings or parties.

Fourth of July was a big day particularly on the river at the Concord Canoe Club at the Monument Street bridge. They had canoe races, tub races using washtubs, tilting matches, where two people in a canoe, one standing up with a pole about eight or ten feet long padded at the end, poking at the person standing up in the opposite canoe trying to push each other over, and a parade of canoes from the Main Street bridge to the Monument Street bridge.

Our swimming at Lake Walden was at what we used to call "the beach", which is now where the public bathhouses are. With the advent of tourists and the devastation the gypsy moths caused to the foliage on the trees, we had to move our swimming spot to South Point. There we built a pier at the end of which the water was about 18 feet deep. Of course, this was after the time the picnic grounds had been given up.

The picnic grounds included a dance hall and a railroad station and was at the opposite end of the lake from the beach along the railroad tracks. They had bathhouses constructed over the water so that the people went into the bathhouse to enter the water. There was a ladies bathhouse and a men's bathhouse. This recreation area was used until forest fires destroyed the railroad station and the dance hall, and gradually the picnic grounds were given up. Huge crowds used to come out from Boston on special trains to spend the day at Walden. There was a refreshment stand but people had to bring their own liquor.

And of course, there were some drownings, and there were several instances where they didn't find the body of the drowned person. One of the guns from the Independent Battery would be taken to the water's edge and they would fire several charges. As I understand it, this blast would jolt the body to float to the surface. I remember distinctly seeing that down two or three different times. I was only about 10 or 12 years old when the picnic grounds were given up but I do remember that.

There was also a race track on the other side of the railroad tracks from the lake. As I remember, it was a bicycle track.

One particular event I recall when I was growing up was the First Parish Meetinghouse fire on April 12, 1900. It was burned completely flat. The cause was some oily rags in a closet that caught fire. They thought they had the fire out at one point but it continued and totally destroyed the building. That was one of the saddest experiences I ever went through outside of death. Of course, all they had to fight the fire with was a hand pump which was attached to a hydrant with about six men on each side pushing the handle up and down to create a pressure to pump the water onto the fire.

Willard T. Farrar, who was the sexton of the Trinitarian Church and the only undertaker in town, went into the vestibule of the burning church and tolled the bell. My brother held the ladder for him, and they escaped just minutes before the bell came crashing down. There was the custom of tolling the bell when a member of the parish passed away. The family would contact the minister and he would have the sexton toll the bell the number of times as the person's age. So Mr. Farrar tolled the bell for the meetinghouse.

There was an incendiary period of time in Concord in the early 1920s, in which no one could accuse someone else about the origin of a fire when there was a lack of clues. In 1923 or 1924 the Trinitarian Church burned of an unknown origin, so presumably incendiary. Then several ice houses were burned and one or two houses set afire, but I don't remember that they were destroyed. The fire department and the police felt they knew who the person was but couldn't actually accuse him of it because they didn't have enough information or clues. He shortly left town and the frequency of fires lessened measurably.