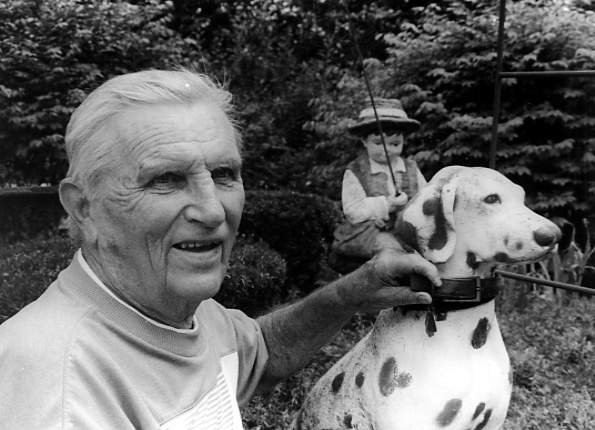

Tom Hayes

155 Williams Road

Age: 81

Interviewed August 22, 2005

Concord Oral History Program

Renee Garrelick, Interviewer.

My mother and father, Bridget and John Hayes, were both Irish immigrants. My mother

came from Galway and my father came from Limerick. They settled in this country sometime in

the late 1800s, but I'm not exactly sure of the date. My father ran a farm in Lincoln. Then my

father got a job with the railroad, and he bought a house on Cottage Lane which my brother still

owns today. It is a duplex now, but it's still owned in the family. They were hard-working

people. My father liked his beer. He made his home brew during prohibition. I remember my

mother yelling because the bottles were exploding in the cellar. Those were happy times.

My mother and father, Bridget and John Hayes, were both Irish immigrants. My mother

came from Galway and my father came from Limerick. They settled in this country sometime in

the late 1800s, but I'm not exactly sure of the date. My father ran a farm in Lincoln. Then my

father got a job with the railroad, and he bought a house on Cottage Lane which my brother still

owns today. It is a duplex now, but it's still owned in the family. They were hard-working

people. My father liked his beer. He made his home brew during prohibition. I remember my

mother yelling because the bottles were exploding in the cellar. Those were happy times.

I was born on the dining room table. Old Doc Sheehan was the old town doctor at that time along with Doc Pickard. Doc Sheehan said to my mother, "Ma, you're not going to make the hospital, get the dining room ready." My other brothers and sisters were there because I was the youngest. I was a mistake, I think. There were eight of us, six boys and two girls. There are three of us left. My older brother Edmund is now 91. My sister Eleanor lives in Waltham. My mother died when I was 13 so my brothers and sisters brought me up. They did a good job. I was well taken care of, well fed, well clothed; I had no problems at all. They still think of me as the family kid at my age.

We lived close to the depot area and there were an awful lot of Italians in that neighborhood. The neighborhood was all either Italian or Irish. Every year the Italians had what they called a street festival. They still have it in the North End in Boston. At the end of the street, they would have all kinds of Italian food and Italian music. A man by the name of Secundo Sabloni, who still lives in Concord in the senior citizens housing, used to play the accordion and Sully the barber always played the mandolin. It was absolutely beautiful. We loved it. As kids, we loved it.

Then every year the Hiberians put on a show at Monument Hall. They were mainly the McHugh brothers, Joe McGann, and McGraths, and Woodlocks. I was only a small kid at the time, but Joe McGann had a beautiful voice. He'd sing solo without any accompaniment. He'd sing "Mother McCree", "My Wild Irish Rose", and songs of that nature. Everybody loved him. The McHugh's were all clever musically. They were all talented.

The cattle show grounds was where we played baseball part of the time. The cattle show goes back to Thoreau times. As a matter of fact, in Thoreau's time, it was called the Agricultural Hall in the cattle show. It eventually burned down, but Thoreau mentions in his journals about everybody getting dressed up good and going to the cattle show for the fairs. The farmers are all hiding out back and drinking rum. We used to practice baseball at the cattle show grounds, but we played our baseball at Emerson Field in what they called the Asparagus League. Concord was all asparagus in those days, and we all worked at the asparagus farms. When we would get done working at night, we would all head down to Emerson Playground to play baseball in the Asparagus League. That league was established in about 1930, and it quit in about 1950 when television came in. We were hurting for money one year for equipment, and John Finigan went to the Town Meeting and asked for $200 to buy baseball bats and equipment. And they gave it to us. We were happier than the devil. It was the happiest time in my life in the Asparagus League. There's very few of us left that played in the Asparagus League. My brother did and he's 91.

The different neighborhoods were part of that league. The depot was one team; Hubbardville, which is Fairhaven Road section of town, was another; Herringville, which was down by Emerson Playground where most of the people came from Nova Scotia or Prince Edward Island so we called them "herrings", was another; then the East Quarter was another and they were all farmers - the Burkes, McHughs, McGraths, Kenneys and Algeos; and then Bedford Street was the other, which was mainly the Dees and the McGraths. So there were five teams. We were dead serious. People would show up at night and be yelling for their section of town. It was a wonderful time. Originally in the 1930s, there was a West Concord team but they dropped out. There were some damn good ball players. In fact, Concord won the state tournament in 1937, and a number of baseball players from our league went out to Kansas to play in national amateur baseball. The people really turned out to watch baseball. There was no entertainment in those days in town. We were all a clannish bunch of people. But we were all together when needed.

Trapping muskrats was a big thing for me when I was a boy. There was very little money around during the Depression. So there were about 20 of us who used to trap the rivers and ponds in Concord. We would trap before school and after school. The man from the Lowell Rendering Company came around every single week to buy the muskrats and he paid an average of about 65 cents. So if I was to catch 10 muskrats in a week, that gave me $6.50. Well, we'd hitchhike to Maynard to the movies, and the movie was only 15 cents and an ice cream bar was a nickel, so we really had entertainment. Well, a few years ago they changed that damn Question 1 and banned all trapping, and now we have a very, very serious beaver problem in Concord. All the brooks in Concord have been inundated with beavers. This brook down here is ruined on both sides of the road. We're trying to get the conibear trap back. The conibear trap is your main trap. In most times, it kills instantly. I have not taken an animal alive out of a conibear trap. They were always killed on the spot. The conibear trap is called that because the man who invented it was Frank Conibear. That was his name. So people got the wrong impression. They think the conibear trap is for trapping bears. It's not; it's a trap that a man by the name of Conibear invented.

A lot of beaver that I caught weighed as much as 60 pounds, and we'd get good money for the beaver in the winter time. Now this time of year they're trapping and just throwing them away. You're not allowed to use the meat or the fur. If we could trap them in December, January and February, the fir is prime. It is the best fir especially made for good coats. The meat is delicious. Of course, the beaver is a vegetarian so the meat should be delicious. I love the beaver meat. I take it to the gun club and they can't get enough.

I joined the Rod and Gun Club in 1939 for $2.00. That was a lot of money in those days. So I had a job with a man named Nick Jacobson who was a landscape gardener in Concord. He worked for many of the rich people, what few rich people were in town because not many of them were real rich but they were richer than we were. So I would get 25 cents an hour for cutting lawns with Nick Jacobson. As soon as I got $2.00 saved up, I went and joined the Concord Rod & Gun Club. I believe if I'm not the oldest now, I'm pretty near the oldest member in the club. Jimmy Powers was quite active in the club.

The club was on land owned by John Forbes of the Concord Ice Company. He was very generous. We didn't have any money, but he let us use the club in the off season and he let us use the land all the time. He finally made an agreement with us and we bought it. We didn't pay very much, and now it's probably worth millions - 46 acres of land that goes back to Barrett's Mill Road. There is a road from Barrett's Mill Road that goes into the Rod & Gun Club if we want to use it. It's a right of way, and all that back land is high and dry so it's worth a lot of money. It's beautiful land. Some people don't like us shooting up there. But our argument is well if you don't like the shooting, we can always sell it for low cost housing. They put up with our shooting pretty quick. The members were just men for years. About 15 years ago, they voted to let women in, and my wife was the first member. My wife is a hunter and a fly fisherman. She loves to fish, hunt, and trap. So she became the first woman president of the club. Her name is Irene Hayes. She was president for four years and she did a damn good job, if I must say. She put on good functions and all. Since then there have been a number of new presidents.

Fourth of July was the big event for years, but the trouble with 4th of July was it was so hard to get workers to put it on. All the old timers that had put it on had all died off, and the young people just had too many other ideas for the 4 of July. So it kind of faded away. We have talked about bringing it back but I don't know if we will or not. Now yesterday for instance, we had a buffet breakfast there for $6.00 a piece and they had everything under the sun for breakfast - all you wanted to eat. It was beautiful. The place was mobbed. That's a good function. They made a little money. The club is still functioning damn good.

At the end of Belknap Street, there is a dirt road that went down to the river and it curved over toward the railroad tracks. Well, we made a tremendous big swimming hole there. We made a beach and dug out the bank and we put up a split rail fence. The boys would camp there sometimes over night with our little pup tents and make little fires and cook out. It was great times. Down by the tracks was where the hobos would always come. We would watch the hobos and they discovered our swimming hole. So they would come up and just live there for three or four days, and they'd play horseshoes with us. They'd go around begging for food of course. They used to come to my house and my mother would always answer the door and tell them to stay outside and she would get them something to eat, but first she wanted them to work. So she'd make them cut firewood. My mother always cooked on a wood stove. My mother was an excellent cook. I remember as a kid the old-fashioned oatmeal, not the stuff they have today. So she'd make them work. I remember asking her one day why she made them work. Well, Tommy, she said, people have pride so if I give them something to do they feel they worked for the food rather than beg for it. When they left, she would always make them four or five sandwiches and she'd wrap them in waxed paper. I can still remember just as plain as day, she'd say "I made you some pressed ham sandwiches." Did you ever hear that expression, pressed ham? I never did either except my mother used it. So for years and years I wondered what was pressed ham. So pressed ham was, believe it or not, what we call baloney today. So they would go off with the sandwiches and they were happy. They were good people, the hobos. Some of them were very well educated and they came from everywhere.

Then over in the railroad sidings, they had cars parked for the railroad workers and they had a cook there and they had a big place for them to eat. They had a parrot there and he could swear to beat the devil. The workers would teach him swear words. Those were fun times. They called them section gangs but that all faded away of course. They'd work different sections of the railroad.

Those sidings that were down at the railroad station would have cars with deliveries of various things. John Forbes would get his ice delivered there sometimes when he didn't have enough. He generally cut his own ice. Then Floyd Verrill would have cattle come in. And then there was lumber that would go to Wilson Lumber. And coal would come in. So all those things were unloaded there. That's how Concord was in those days. As boys, we loved to hang out there. The hobos had the best stories of riding the rails. But the hobos were always looking for the police because the police would always drive them off.

Down on Sudbury Road near where the Stop & Shop used to be was Johnny Moreau's blacksmith shop. Johnny was a big strong blacksmith. We'd go down and hang out when we were kids. But he was a real grouch. He was a real curmudgeon but he was spotless. He had the most spotless blacksmith shop I think in the country. He had a place for everything and everything was in its place. For 25 cents he would sharpen our skates for us. Then up Grant Street was Tom McGann's blacksmith shop. They were kind of crude. There was a man by the name of George Dingle, a big fat man, who worked for Tom McGann. He'd take a paper bag and make a hat out of it and put it on his head. He had a big, big apron and he'd wear a belt around his apron. He reminded me of Wallace Beery in the movies. They used to do a lot of wheel work. They were wheelwrights. In those days there were still a lot of wagons pulled by horses, and they'd fix the wagon wheels.

In the winter time, the town used to hire people to shovel snow. We had plows but a lot of the plowing was done with horses. Around the depot they'd shovel snow by hand. They'd get a gang of 15 or 20 workers to clean off the business section of the depot. Old Deignan Curran used to haul the snow. I think a lot of it was hauled to Emerson Playground. They hauled it in what we called pungs. They had big runners on the pung. And they'd fill the pung with snow and get the horse going, and we as kids would run along and jump on top of the pung and get a free ride.

I was wild about that the town didn't keep Johnny Moreau's blacksmith shop as a historical site so the children today in Concord could see what it was like in rural times in Concord. I think Johnny would have given the shop to Concord because he loved it so much. I think the blacksmith shop stayed until the 1950s. Johnny made a lot of money when there wasn't much money around. I used to get a kick out of him when he'd shoe a horse, he'd tie up one hind leg so the horse couldn't kick. He was a real grouch but a nice guy. He was good with us kids but he was grouchy with us. He'd never chase us away. He always let us hang around. We were fascinated.

All the boys in town seemed to make their own kayak and I made my own kayak. We'd go along the river and pick water lilies and we sell them in bunches to people in Nashawtuc Hill for 15 or 20 cents a bunch. I think the people up there felt sorry for us so they'd buy them. That was a good income for us too. Between cutting lawns in town for 25 cents an hour, trapping muskrats in the fall and winter, and picking water lilies, we always seemed to have pocket change. Then we'd hitchhike to Maynard to the movies which were 15 cents.

Where Arena Farms is now there was no Route 2 and there was a great big mud hole there. We loved it because we used to go there fishing believe it or not. And we'd go there skating in winter time especially at night. It was good. Then about 1933 or 1934 Route 2 was built and they cut the mud hole right in half In fact, they filled half of it in.

Jimmy Powers on most Sundays at 1:00 would gather everybody together and hike up to Fairhaven Bay. He led the group and would tell us about the history of the area. We would go hike from Fairhaven Bay to Farrar's Pond on Route 117 in Lincoln, hike past that and cut back into Fairhaven Bay by what we called Wheeler's camp. Wheelers and Wrights lived in those camps there for years. I don't know if they still own that property. Then we'd hike back to Jimmy's and that was our day. It was really fun. We made our own entertainment.

I was a mailman for 30 years, and I loved it. My route was about 12 miles long. I used to walk it. The route was in the Hubbardville section, Fairhaven Road, Arena Terrace, all that area. The dogs would go with me. I looked like the pied piper because the dogs followed me. I got to giving them yummies. When they knew I was going to give them yummies, they wouldn't leave. They'd go with me the whole route. Some of the dogs were kind of mean but once I tossed yummies to them, they got used to me.

I really got a close look at that section of town. There were still a lot of old-timers there like Bob Issennee. His parents came from Russia and he didn't like our tomatoes in this country, so he sent back to Russia and got tomato seeds. Bob Issennee went to Florida every winter and I would raise his seeds for him in flats. I still have them in my garden today. He had a Colt 45 pistol, and he told me his father's father came to the '49 gold rush in this country. Somehow he got this 45, and when Bob died, it was still in the Issennee family.

Toward the end before my retirement, I rode in a mail truck on my route. I gave a ride to one dog named Muffy that lived on Adin Drive with another Hayes family. She'd wait at the end of the street and when I would pull up, she'd jump in and lick my face. So I'd drive my route with her and after the route was all done, I'd stop at the end of the street and tell Muffy to go home and she'd jump out of the truck and go home, but the next day she would be waiting for me. I loved that dog so much. I was a mailman from 1955 to about 1986.

I built this house myself starting in 1954 and I moved in the following July. I had no money so I had to do everything myself so it took me nine months to build it. This neighborhood was called Easy Money farm. The reason it got that name was that all the old-timers always called it easy money. They claim at that time in the 1920s there were all kinds of farms in Concord. Farms weren't worth anything so a lot of farms changed hands in poker games. Some of the camps at White Pond exchanged in poker games. So at this camp here, there was an asparagus shed down the road here and I think the guy that owned the farm at that time was named Art Saunders. They used to have poker games down there every Friday and Saturday nights, big poker games. One of the farmers put this farm up in the poker game. Another farmer won it and from then on it was always called easy money. I have a nice garden out back.

I did a lot of hunting here because I had this all to myself then. I shot pheasants and partridge and rabbits. Everything I shot we ate. Nothing was wasted. Of course now, it's all grown up. It's still nice, but it is not as nice as it was.

Williams Road was named after Frank Williams. The Williams family settled here in the late 1700s. I used to laugh because they were an old couple then and every Sunday morning they'd hike to church all the way down in West Concord and hike all the way back without fail. The only trouble with Frank was if you saw him when you were hunting, he'd keep you talking all day, so I could never go hunting. They lived back in the woods there and wouldn't see people often. That land now is all conservation land that the town owns. That was good farmland back then. Up around Sanborn School was all asparagus growing.

I went into the 454th Bomb Group, 15th Air Force, 737 Bomb Squadron. I didn't know when I got there, but Humphrey Hosmer from the Hosmers on Elm Street was there at the same time. I didn't know Caleb Wheeler was there at the time either. It was the same Air Force, but a different group. Humphrey and I were together. That family goes back to colonial times in Concord. Mrs. Hosmer was a Buttrick, and they go back to the battle of the bridge. I met Humphrey one day when other crew members and I were drinking wine outside the base because we thought the base was too noisy. Well, Humphrey was officer of the day. We were drinking out in this field and along come this officer and he saw us. Humphrey looked and said, "I think I know you." I said, "I think I know you too." So he told us to get our drinking done and get the hell back on base. Humphrey asked if I got the Concord Journal and I did, so I gave it to him. Humphrey and I flew a lot of missions together. Humphrey was lead navigator. He was a smart man and a good navigator. Everybody thought the world of Humphrey. If he was leading the group in the squadrons, we were pretty sure of not getting lost. Some of the runs were over 600 miles and they were small targets and you had to be pretty accurate. And Humphrey was good. He was a damn good man.

Our mission was to damage German industry like the Ploesti oil fields. They felt if we could knock out the Ploesti oil fields that would cut down their war machine because 90% of the German oil came from Ploesti. Even after we got done bombing the oil fields, the Germans came up with synthetic oil. They had places like Aschaffenburg, Germany, that was a synthetic gasoline plant and they had places called Brux. They were making synthetic fuel. Although synthetic fuel was not as good as ours, we had 100% octane gasoline. As good as their synthetic fuel was, it could never come anywhere near our octane. So as a result the German fighters were nowhere near as good as our fighters in flying. In getting Budapest, I was on that mission and it was supposed to be an easy mission. As far as I was concerned, it was a milk run. A few weeks later I got a letter from Mrs. Caleb Wheeler telling me her son went down on the mission to Budapest on July 2. Well, hell, I was on that raid. So she wanted to know if I could find out anything.

So the kid called Okie because he came from Oklahoma, who was killed a few weeks later and I hitchhiked up to Caleb's group near Foggia, Italy. I went in to his commanding officer and told him who I was and where I was from and I had a letter from his mother and she wanted to know if I could find out any information. The commanding officer said he would like to tell me but he couldn't tell me a damn thing. I asked why and he said because the information has already gone out. If I tell you anything, it will probably be conflicting. I'd rather not tell you anything other than what Mrs. Wheeler has already got. I asked to talk to others that went on that mission and he said, "Oh, no, I can't let you do that either." But in all fairness they were probably a half mile behind us in another group, I did see a B24 pull out of formation and I told my pilot about it and he said to keep my eye on it and then all of a sudden, bang, bang, and then the parachutes opening up. So I wrote to Mrs. Wheeler that it was an easy mission but I did see an airplane that apparently got hit by flack and I counted eight parachutes getting out of that plane. I wish I never said that because I think I may have given her hope. We only lost one or two planes in that mission but none in our group at all. We landed and I didn't know Caleb was on that mission. Humphrey had come home and Mrs. Hosmer had told Mrs. Wheeler to write to Tommy Hayes who's in the 454 to find out what he can.

I came home a while later, and I was shopping at the First National Store in Concord and I had the 15th Air Force patch on my jacket and she came up to me and asked who I was and I told her. So she introduced herself He was missing in action first. I can understand why they wouldn't tell me something. If I told Mrs. Wheeler something, it might have conflicted with what they had told her. They had told Mrs. Wheeler that he was missing in action and more news would follow. But he was killed.

Recently I met his brother, Joe Wheeler. After all these years I was always going to go see Joe, and I went to see him on July 2 of this year which was the anniversary date that Caleb was shot down. He got shot down on July 2, 1944. We were hitting railroad yards in Budapest and Joe didn't know that. The Germans were packing up at that time and they were evacuating. We hit the main railroad yard where all the train tracks meet. We went in and bombed them of course and we did raise hell with the tracks. Lots of times we missed though. In fact, I said to my bombardier one time in a joking manner, you know if it wasn't for gravity I don't think you could hit the ground.

There was a Jewish boy named Rudy Haase. When Hitler took over in the 1930s, his family had a lot of money. The Jewish people with money had a chance to get out. They saw the writing on the wall, but they were only allowed to take so much money and so much baggage and everything else had to be left. The Germans took everything from them. So they went to England in 1934, and then from England they came to this country and they settled in New Jersey. Rudy enrolled at Princeton. Then he left college and joined the Air Force. All my four officers in my crew, co-pilot, pilot, navigator and bombardier were all college men. The rest of us were all high school men. Rudy was always talking to me about when the invasion was coming, when was it coming? Well, he was killed two days before Normandy and Angio Beachhead. It was sad. He had more damn courage than any man I had very met. He was very proud of his faith. I said, "You know Rudy, if we should go down or get hit and bail out over Germany, the Germans are going to give us a hard time, but you being Jewish they're really going to give you a hard time." He said, "After what the Nazis did to my people what more can they do to me?" And he was so right. So we would turn the German news on, and Rudy would interpret for us.

I was called Sparks because I was radio operator too. You had two jobs and I was radio operator and gunner. In combat you never touch the radios. You always maintained radio silence because the Germans could put a fix on it and tell where we were. On one mission somebody says, "Sparks, get some music on." It was so cold when we were up about 20,000 feet, it was about 40 below zero even though we had electric suits. I got the BBC from England and they were playing "Danny Boy". One of the crew had a beautiful voice and started singing along over the loud speaker. We loved it. I never forgot that. A week or two later, he got killed.

The sad thing about Okie, the Major said he needed two gunners for tomorrow. I had 49 missions and Okie had 49. Okie said he wasn't volunteering for nothing. So the Major asked me and I said I wasn't going if Okie wasn't going. That's how I felt. I loved Okie; I admired him. Anyway we were leaving the tent and I said, "Well, tell me sir, find out where the mission is and I'll think about it." The Major came back about an hour later and told us the mission was up to Bologna, Italy, and it should be a milk run because the Germans were pulling out. We were going to hit the marshling yards again. So Okie wouldn't go but I said I would go. That was my last mission. The next day he told Okie he was flying tomorrow, and Okie was killed the next day over Gyor, Hungary. I went to town that morning because I was getting ready to come home, and I walked into my tent and everybody looked at me. I said, "Okie bought the farm" which meant you got killed, and they said yes. He was a nice guy. I've never gotten over Okie being killed. If only he would have listened and came with me that day, we would have made it, or if I had listened to Okie which I always did, I'd be dead too.

So when I got back after my last mission and I got off the plane, I grabbed a hunk of the dirt and I kissed it. They always give you a shot of whiskey after the missions. The priest was there and he gave me a double shot and I said I wasn't going to take it today. I gave it one of the other gunners.