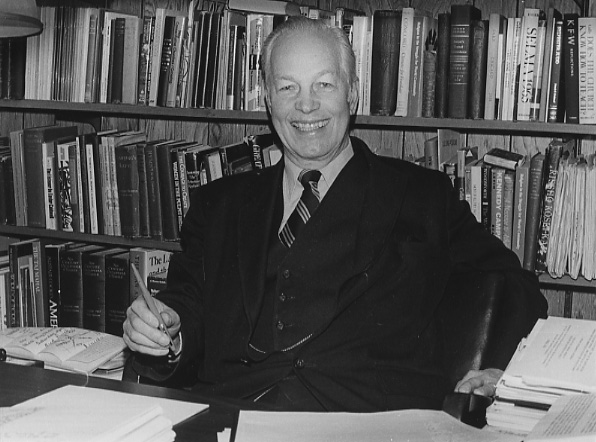

Reverend Dana McLean Greeley

First Parish Church

Age 73

Interviewed March 17, 1982

Concord Oral History Program

Renee Garrelick, Interviewer.

The First Parish Church was the only church in Concord for

the first 200 years and the Church and the town were essentially

one. The Church was always a very small body of people,

communicants who were the full members but the parish was the

whole town, and they all looked to the church for leadership and

for their moral standards as well as for their worship.

The First Parish Church was the only church in Concord for

the first 200 years and the Church and the town were essentially

one. The Church was always a very small body of people,

communicants who were the full members but the parish was the

whole town, and they all looked to the church for leadership and

for their moral standards as well as for their worship.

The town was founded by legislative action in 1635, the church was organized in 1636 which was before the people came out here, it was organized in Cambridge in the church that had just been gathered in Cambridge. And from that time when they settled Concord in 1636 until literally 200 years later or 190 years later, 1826, it was the only church. I have to say with a couple of exceptions because two very small groups, dissident groups, organized but existed for a few years and then went out of existence again. The Congregational Church, the Trinitarian, was established in 1826.

The town and the parish were one, the church was the only church in town practically speaking until 1826 and interestingly enough it wasn't until 1855 that the First Parish and the town were separated which was about twenty years after the state legislature had voted to separate church and state.

The Unitarian and the Universalist denominations both go back to the end of the 18th century and both were more formally organized in the beginning of the 19th century in this country. There were Unitarians and Universalists in Europe earlier but in this country the Universalist denomination was in one very important respect the reaction against the Calvinism that was the dominant religion of the time particularly in New England. The Calvinism of that day regarded all people as born in a state of sin, human depravity was one of their principle beliefs and they believed of course that God was a God of anger and rath, and although Christ had been crucified for man's redemption nevertheless only a certain segment of the people would be saved. Others damned eternally would be suffering hell fire forever.

The Universalists were born really to proclaim a God of love and what they call universal salvation thus the name Universalist not partial salvation but universal salvation, and for a very long time, the principle thesis or belief of the Universalist denomination was the ultimate reconciliation of all souls with God. That was even before Unitarianism was extant or prevalent in Boston or New England. The Unitarians reacted against the same Calvinism but their emphasis was with respect to human nature rather than as much with respect to the nature of God.

The Unitarians felt that they could not believe in a God who would condemn people to eternal torment but they also believed that people were essentially good or certainly they hadn't been born in a state of depravity, they were not primarily sinful. Although the Unitarians believed in a God of love they also more emphatically accentuated the dignity of human nature and the divine possibilities of all people.

The Universalist became Unitarian in that sense in about the second generation. They affirmed their belief in a God of love but they also after the first generation rejected the trinity, the idea that Christ was a God, that his sacrifice had atoned for the sin of Adam, they became Unitarians in the sense that they gradually adopted the idea of the oneness of God, the humanity of Jesus and the dignity of human nature. So the two denominations grew closer and closer together all through the 19th century and though at the beginning of the 20th they really talked about merger, it wasn't until 1961 that they became one denomination.

At that time I had been in young people's work and the two continental young peoples groups joined before the two denominations did. I had been for merger and was the last president of the American Unitarian Association and it so happened the first president of the merged group, which was the Unitarian Universalist Association of North America.

I have been in the ministry since the early '30s. You mentioned my age as 73 and I was in the ministry at the age of 23 therefore. I started my ministry in Lincoln in February 1932, while I was still in divinity school. I was there for two years and then went to Concord, New Hampshire. I was there less than two years when I received a call to the Arlington Street Church in Boston which was a kind of mother church for the Unitarian denomination and had been for 150 years, and I couldn't really turn that down although I wrestled over it for some time before deciding to go to Boston. I had, for me, a very wonderful twenty- three year ministry there. I left Arlington Street Church in 1958 for denominational work.

William Ellery Channing was the minister there, the greatest preacher and minister in our history if you consider people who devoted their life to the formal ministry of the church and he was the spiritual father of both Unitarianism and they say of the flowering of New England. When I went to the Arlington Street Church, I held some services for people who had been there in Channing's ministry. That was amazing to me, the continuity, it seemed to me that it was a long time between the early part of the 19th century and my time in the 20th century but one year after I went I had the funeral for a man named Henry Monroe Rogers. He was 98 at the time, a very distinguished Bostonian and musician, I had his funeral and he had been christened during Channing's ministry, that surprised me. But there was a lot of continuity still in those days in that church and in the denomination. It has always been a small denomination and the number of interrelationships and even the continuity through those relationships is normally quite impressive.

This year we are celebrating 100 years since Emerson's death. I was still at Arlington Street Church in 1953 which was the 100th anniversary of Emerson's birth and I happened to chair the committee for the American Unitarian Association. So we came out here, one of our celebrations was in May 1953 a large gathering in this church which was the principal gathering really at that time for the observance of his 100th birthday. I'm rather interested now coincidentally to find myself chairman of the 100th anniversary committee continentally that is observing memorially his death, April 27, 1882, and we will call the week between April 25 and May 2 all over the country, Emerson week, and we are having the selectmen in our town here issue a proclamation to observe Emerson week and Emerson day the exact anniversary of the death April 27 here in Concord.

Emerson was, of course, as great an influence as Channing. There were differences between their lives and their influences and I spoke of Channing as being the greatest unquestionably who remained in the parish ministry all his life. Emerson in a sense was a minister all his life. He was installed and settled only in one church, The Second Church in Boston, for many reasons he left that church, understandable reasons, he preached in East Lexington for nearly a couple of years but never was officially settled there but his daughter Ellen at the end of his life said again and again that his essays and his addresses were his sermons. I believe he thought he was always in the ministry, he never gave up the ministry but the Lyceum platform was his pulpit rather than within the church.

A high percentage of feminists of the 19th century were both Unitarians and Universalists. Actually the Universalists had many more women ministers even than the Unitarians. At the end of the 19th century, in the 1880s, there were a large number of women Universalists ministers and in the state of Iowa the majority of the Universalists ministers for twenty or thirty years back then were women. Among the actual leading reformers for women's suffrage and women's rights, a majority of them were Unitarians, I think of Susan B. Anthony, Julia Ward Howe, Mary Livermore, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, a lot of names that you think of in addition to those which were well known right around here such as Margaret Fuller and nobody was more brilliant than she or more extreme in her influence, and Elizabeth Peabody and Elizabeth Hoar even, a lot of them were strong suffragette or women's rights people in those days. And Louisa Alcott by all means must never be forgotten!

If you are making a record here of a rather personal nature for posterity's sake or what little segment of it is ever interested in reading our library's archival documents, I think from the earliest days in my own ministry, I had a real concern for social action and social questions. I remember when I first went to Arlington Street Church, I had just been advocating a resolution in the denomination with regard to conscientious objection, to recognize conscientious objection and that was splitting the denomination to some degree in those days, I became very early, almost too young, a member of the Planned Parenthood Federation in Massachusetts, and in those days rather active on the question of parochial school transportation.

I was opposed to it, I'm afraid I was a little bit narrow perhaps although I would still take the same stand with regard to separation of church and state, but on several of those issues which seemed to be in those days too much protestant/catholic issues but the Jews were lined up with the protestants by and large. It wouldn't be quite the same today. On many of those issues I did speak my mind quite frequently and always on the question of world peace or peace questions. I remember that my church in those days partly as a result of my positions I guess, my church in Boston, Arlington Street Church, I think somewhat unjustly got the reputation of being a little anti catholic. I think the last twenty-five years of my life I've been more concerned about interfaith work and so forth but in those days, the issues did seem to divide us.

When Adlai Stevenson was campaigning over the weekend before the election in his second attempt at the presidency, he was staying at the Statler Hotel within a hundred yards of my church and I thought he might come to Arlington Street Church Sunday morning, but I learned some days later that the leading democratic advisors in Massachusetts had asked him not to go to Arlington Street Church. So he went out of the city and went to church in Cambridge but he was a Unitarian and would have come to my church. That bothered me a little but I know it was because we had taken some real stands that perhaps politically didn't play into his interests. That was a little ironical because I was called upon to give the eulogy at his funeral when he died in his home church in Bloomington, Illinois. Well, I was fairly outspoken I guess in those days. I guess the most distinguished occupant of a pew in my church there was Martin Luther King. He and some of his classmates used to come to church at Arlington Street Church when he was in Boston University School of Theology, but I did admire Bishop Austin very much who was then bishop of the Methodist church in the New England area and who later I think contributed very significantly to the undoing of Senator McCarthy. Mr. Welch of legal fame perhaps was the greatest single factor but I think maybe Bishop Austin was the next most important person in getting at the facts about Senator McCarthy.

I was on the American-Soviet Friendship Committee way back in the '40s. That was a fairly unpopular position, I may have been a little naive in those days but I would rather err in that direction. I have friends on both extremes and I think I prefer to err if in any direction in the direction of naivety and of friendship or reconciliation but for a period of time that was a difficult position to take. I think I would feel the same way today in spite of all the paranoia and panic and possible real legitimate friction between the two countries, I would much rather strive for understanding and detente or peaceful relations at almost any cost.

Within the last three or four years the women's movement has had a greater impact on religion maybe than it's ever had before. To be sure in the women's rights movement in the 19th century it had a direct relationship to religion and of course it did also at the time of the women suffrage movement in this century. But in the last few years I think it has really become far more articulate. The women's movement with regard to the actual semantics problems in relation to deep rooted concepts that of course made woman inferior to man, and those date from early Christian history and even from St. Paul who said women should remain silent in the churches. There are no women priests, there are some in the world but they are not recognized yet in the catholic church the largest Christian body by far, and many other denominations have not recognized them yet. Now I don't quite feel like dismissing the tradition of which that is a part. There is a lot of good in all those traditions but humanity as a whole has got to think much more about that problem. I would say that the black rights movement was very important in our history, the whole question of the third world and developing nations has been a major revolution, the industrial revolution was a tremendous factor in our society but I think maybe the women's revolution from the historian's point of view 500 years from now may be recognized as the greatest of all of the transformations in human society in the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries.