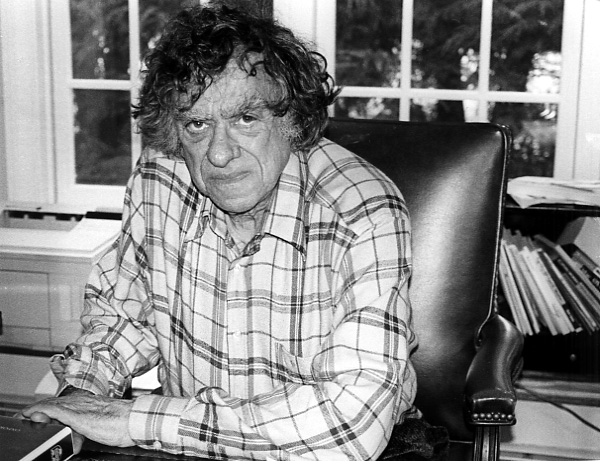

Richard Goodwin

Presidential Advisor and Speechwriter for John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson

Interviewed February 2, 1999

Year of birth 1931

Concord Oral History Program

Renee Garrelick, Interviewer.

Richard Goodwin offers us a special insider's look at the decade of the 1960s through his active participation in national politics as advisor and speechwriter in the administrations of John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson and through the presidential campaign of Robert Kennedy and Eugene McCarthy.

The significance of the Civil Rights movement was realized in a speech that you wrote for Lyndon Johnson considered the most important speech of his political career. You wrote, "At times history and fate meet at a single time in a single place ... "

" ... So it was at Lexington and Concord, so it was at Appomattox and so it was last week in

Selma, Alabama." At that time blacks were effectively denied the right to vote in the South. There were

all sorts of rules, registrars wouldn't register them, and so in order to protest lack of voting rights Martin

Luther King led a march from Selma, Alabama, and he was set upon by units of the Alabama state police.

There were serious beatings shown on national television and the country was outraged by George

Wallace's behavior as the then Governor of Alabama. Then of course Johnson was getting a lot of

pressure to send in troops, but he didn't want to do that right away. He thought that would be imposing

reconstruction on the South all over again but finally he managed to convince Wallace that he couldn't

protect the marchers. He really meant he didn't want to protect the marchers, and he was using that

pretext to send in the national guard. But his response was not simply to protect the marchers and the

protesters, but to send a bill to Congress which would effectively grant voting rights to Black America.

He summoned a joint session of Congress as a national emergency, and he stood there that night before

the joint session of Congress and announced his bill to ensure, through Federal registration, voting rights

to blacks in the South. Of course, from that day forth blacks in the South have voted and they've become

an important force in politics.

" ... So it was at Lexington and Concord, so it was at Appomattox and so it was last week in

Selma, Alabama." At that time blacks were effectively denied the right to vote in the South. There were

all sorts of rules, registrars wouldn't register them, and so in order to protest lack of voting rights Martin

Luther King led a march from Selma, Alabama, and he was set upon by units of the Alabama state police.

There were serious beatings shown on national television and the country was outraged by George

Wallace's behavior as the then Governor of Alabama. Then of course Johnson was getting a lot of

pressure to send in troops, but he didn't want to do that right away. He thought that would be imposing

reconstruction on the South all over again but finally he managed to convince Wallace that he couldn't

protect the marchers. He really meant he didn't want to protect the marchers, and he was using that

pretext to send in the national guard. But his response was not simply to protect the marchers and the

protesters, but to send a bill to Congress which would effectively grant voting rights to Black America.

He summoned a joint session of Congress as a national emergency, and he stood there that night before

the joint session of Congress and announced his bill to ensure, through Federal registration, voting rights

to blacks in the South. Of course, from that day forth blacks in the South have voted and they've become

an important force in politics.

Johnson was very committed to civil rights. He grew up in an area of Texas which is not particularly racist. His father was attacked by the Ku Klux Klan and he was very anti-Klan. He taught young Mexicans when he was a young teacher down in Johnson County. In fact, he mentioned that in his speech, I remember. As he said, while he was a Senator from Texas he felt very strained in what he could do in terms of civil rights, although he had done some things. Once he got to be President he really moved forward. In fact, the year before this bill he passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 which was originally sent to Congress by Kennedy but didn't seem to have much hope getting through and he really rammed it through Congress. That was the bill that ended legalized apartheid in the South. Segregation was then legal in restaurants, hotels, restrooms, and this bill made it illegal. In two years blacks probably took the greatest strides forward under Johnson than they had since the Civil War.

Going back to that speech, I had done most of Johnson's major speeches, the big ones. I was actually having dinner at a friend's house in Georgetown and somebody came in and said Johnson just had a meeting at the White House, but no one was there except one of his assistants Jack Valenti. He announced he was going to address a joint session of Congress the next night. So I went home that night and picked up my White House phone and had no messages and I thought "Thank God, that means someone else is writing it," and I went to sleep. I got to the White House the next day and Jack Valenti was jumping up and down because he had woken Johnson up in the morning as he usually did, and Johnson turned to him and asked, "How's Dick coming with the speech?" Valenti said, "Well, I didn't ask Dick to write it." He said he asked Horace Busby who was a fellow from Texas. Johnson turned him and said, "You asked Horace Busby to write that speech? Don't you know a liberal Jew has his hands on the pulsebeat of America and you asked a Texas public relations man to do it?" So Valenti came running over to me and said, "Get to work." So I started at about 8:00 in the morning and I sent it over page by page. I never got a chance to read it over, and the last page came out of the typewriter about 5:30 or 6:00 in the evening just in time to go on the TelePrompTer for the 8:00 delivery on the three networks. I stood there in the well of the House of Representatives while he delivered it, which is the same place where the talk about impeachment and Monica Lewinsky is happening today, and the reaction was just overwhelming. In the middle of the speech he was interrupted by applause 30 or 40 times, several times there were standing ovations from the entire Congress. I remember at one point he said, "It's not just blacks but all of us who must overcome the heritage of bigotry and justice and we shall overcome" which was then the anthem of the civil rights movement. There were Senators in tears, Martin Luther King cried when he heard it. It was an extraordinarily emotional moment. And the bill passed. They went to work and started registering blacks, and of course, that changed the face of American politics.

A speechwriter at that time was part of national policy, part of the inner circle from the time of Roosevelt on. You had almost daily contact with the President, you were at Cabinet meetings and National Security Council meetings. It was enormously helpful in terms of writing speeches. Firstly, you got involved in other things besides writing speeches. Secondly, you knew what the policy considerations were, you knew how the President was thinking and how he thought about certain things so you were able to do a much more effective job. You didn't have a lot of intermediaries between you and the President. Today there are the Dick Morrises of the world and the result of course is the quality. That was true of Sam Rosenman in Roosevelt's time, Emmet Hughes in Eisenhower's administration, Clark Clifford with Harry Truman, and I was during Kennedy and Johnson. In fact I belong to a group called The Lemuel Lowell Society. Lemuel Lowell was Calvin Coolidge's speechwriter. So only former presidential speechwriters can belong to the group. We have a dinner about every two years in Washington. You can't get into the group officially until your President is out of office. We still have a member that worked for President Truman and on up through certainly Clinton.

It was almost accidental that I coined the phrase "The Great Society." Johnson was looking for some kind of slogan that might appeal and focus on some of his domestic aims. Just in the course of writing a speech I wrote something like "in our time we have the opportunity to move not just toward the rich society or the powerful society but toward the great society." And the phrase stuck. The press began to pick it up. Johnson liked it, and so then we decided to do a full-dress speech which we did out at Ann Arbor, Michigan. The content was mapped out and dictated by the problems at the time, most of which remain problems whether it is poverty or urban decay or education or what we now call environment but what we called natural beauty. These things were all part of it.

There was a new cabinet position developed called the Department of Housing and Urban Development. We wanted to name it the Department of the Cities but the construction union didn't want us to do that. The War on Poverty itself was a separate unit headed by Sargent Shriver who was John Kennedy's brother-in-law. So we launched all of that. Then the war in Vietnam came in and froze all of that and we lost the war on poverty. It's sad that just three years after this speech, Johnson couldn't even attend the Democratic convention. The war immobilized all the energies of government and sucked up all the money. It was a great tragedy, the war. It was an enormous error by Johnson to keep people there and he was vilified. He would have been booed at the Democratic convention.

Johnson had the capability of getting legislation passed through Congress. He passed the poverty program, food stamps, civil rights. He was passing legislation so fast that I remember some time in 1965 I sat down with Bill Moyer and said, "We've got to get some new laws, he's getting them all through." He was a master at dealing with the legislature. Again until the war, then it became impossible. He knew every member of congress. He had a whole file cabinet full and he knew all their habits, what they wanted and what their districts were like, and he would use all of that. He would sweet talk them, push them, promise, whatever worked. He spent a lot of time at it. Clinton has none of that. I don't think he has a friend in Congress. He doesn't know much about them and it shows up in the fact that almost nothing that he said he wanted is getting through. It's easy for the Republicans; they don't want anything. So they don't have a problem. Reagan never wanted to pass anything much.

There was a lot of energy in Johnson's administration. Bobby Kennedy didn't like Johnson but he said he thought Lyndon Johnson was the most formidable individual he had ever met. And it is true. He just dominated people. He had a lot of stories. He was an impressive man. He was overwhelming. When you talked to him, he would stand right next to you, and he was six feet four and I'm only six feet and he would get right up to you. When somebody gets that close to you and they're huge, it's very disconcerting.

It was very difficult to break with him. When the war came in 1965, it effectively froze everything that I was working on -- the great society, civil rights. But I will say, even at that point, I was convinced he would get out of the war because it was an unwinnable war, do a face-saving retreat and get out of there. When I left I stayed on friendly terms with him for a few months, but then finally I felt compelled to break away. The issue of the war ended our relationship forever. I left at the very end of 1965. He decided to send in combat troops which really made it an American war. It was no longer a Vietnamese war and just pretending to help. At that point there was no great society or war on poverty or anything else for that matter so I left then. I finally broke with him on the issue of the war and I became part of the anti-war movement on the political side of it anyway and went with McCarthy to New Hampshire and with Bobby Kennedy.

Bobby Kennedy was my last political friend. I was very close to Bobby. After I left the White House, I'd see him two or three times a week. We went to Latin America together. I felt very close to him personally. I had worked with him through the Kennedy administration somewhat. He and I were on the same side of issues in Latin America then. We became good friends. Finally when he got into the race, I was with Gene McCarthy at the time and I stayed with Gene McCarthy because I had committed myself to him. Then when Lyndon Johnson got out and the whole reason for wanting McCarthy was to beat Johnson, and that reason was gone, then I went over and joined Bobby. I was with him through the campaign until he was killed.

He had a 50/50 chance of getting the nomination. Then most of the delegates were not chosen at the primaries. The majority of the delegates were under the control of local or county or statewide bosses. Johnson really wanted to keep Bobby from being nominated. I think that is one of the reasons he got out. We were winning in the primaries but that might not have been enough. We'll never know. He and I were discussing that the night he was killed, what he ought to do and whether McCarthy would now drop out. I think McCarthy's supporters would have put a lot of pressure on him to drop out. They were beaten in California and the next primary was New York.

I was working with John Frankenheimer in Malibu on Bobby's campaign and we went in to the Ambassador for a victory party for the returns. He had lost in Oregon and it was the first time any Kennedy had ever lost an election. So we were there and we talked and we were going to go down with him to the ballroom. I got a call from a key McCarthy guy at that time and we were talking and the last thing I knew, he tapped me on the shoulder and said, "I'll see you afterwards at the Factory which is a Los Angeles discotheque." He went downstairs, and I suddenly heard the shouting on the television. We went to the hospital and spent all night at the hospital in case he regained consciousness. They said he's going to die and they turned off the machines. I was there in the room when they turned off the machines.

Backing up to John Kennedy and the first time I met him. I met him when I was in law school. He had a little apartment up on Bowdoin Street in Boston and a friend of mine who was in the state legislature from Brookline wanted me to meet Kennedy who was then Senator. So I went up to his apartment. All these people were hanging around. Frank Morrissey took our coats. So I was ushered in to see him. There were a lot of people waiting to see him. He was always looking for fresh young people so he said, "Well, look me up when you're in Washington." I was going down to clerk for Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter. So that was it. I dashed out and got back on the subway to go get ready for exams for law school. I didn't want to waste any more time. Then when I was down on the Supreme Court, I did stop over to see him once. After that I just said if there is anything I can help with in his campaign, let me know. And I went off and did something else, I did the investigation on the TV quiz shows. About half way through that, I got a call from Ted Sorenson who asked me if I would like to try my hand at writing a speech. I had never written a speech, but I did a draft and then another and they hired me. I would work up in the Senate office with Sorenson. What I hadn't known is they needed another speechwriter, at least another writer, because Sorenson was trying to handle everything himself which is impossible. I didn't know there were lots of people looking for this job so I guess I won the competition. But those two five-minute visits with Kennedy were the only times I had seen him before.

The campaign was fantastic. First of all, it's exhausting. We were the only two who traveled with him. We had a whole writing team in Washington for the amount of volume of stuff you have to turn out, but Sorenson and I were the only ones who traveled with him. We spent 60 days on the Caroline which was a twin-engine propeller-driven plane, bouncing around the country. It used to take us 22 hours to cross the country. Nixon had a jet of course. This was a family plane. It was terrible. It's hard to write on a plane that bouncing. So ultimately it is very exhausting. You get up in the morning and the phone would ring in the hotel room. You had to stumble to the window and see what state you were in looking for a sign, Chicago National Bank or the Idaho Farmers Cooperative. Oh, we're in Idaho now. It was 60 straight days, unremitting, sleepless nights. We always thought he would win. But at the end you can tell it was getting closer. Nixon was gaining. Another week and he would have won. Kennedy felt that too. You could tell. He didn't say it but you could tell. We came up here to Boston and then went to the Cape and waited for the results like the rest of the country.

Kennedy was romance and Nixon was safe. That's what it was really. But he also was Catholic which hurt him a lot in the election. It's hard to imagine that today, but his election sort of eliminated that issue but there still are parts of the country where that is an issue. He was young and a different kind of guy. He could talk to people. Whatever you say about Kennedy he was killed only after three years. If Roosevelt had been killed after three years, he couldn't get us out of the depression, he didn't prepare us for World War II or Lincoln after three, we would have lost the Union. It's very hard to tell what Kennedy might have accomplished. He had a capacity to generate energy. He made people feel that everything could be accomplished. Even those who were against him. Look at all the big social movements that sprang up then, the women's movement, the civil rights movement, that was the atmosphere of the country. He made people feel somehow that they were better than they thought they had been. Even the people who fought him or protested him, they felt it made a difference with him in office. He was moving things in a good direction.

Roosevelt had the good neighbor policy and we had very good relations with Latin American. But after that we didn't have good relations with them and we began to support every tin horn dictator down there as long as they were protecting our companies and with the cold war as long as they were anti-Communist. So the result was when Nixon as vice president took a trip there at the end of the '50s, his car with the American flag on it was spat on and he was almost killed in a riot. Then Castro came in in 1959 and all of a sudden we had communists 90 miles off shore. So there was a serious deterioration in a part of the world that in cold war terms became increasingly important. We had a historical relationship. So Kennedy's Alliance for Progress was really a break from those past policies. We extended aid, a lot of money for development, increased trade, but more importantly he insisted a condition to all of that was that each country make democratic reform a political goal. We took three trips to Latin America. There were huge crowds cheering. I remember one night we were in Columbia at the Presidential palace and he was going to give a speech that night. I was sitting with him and the President of Columbia, a very distinguished oligarch. Kennedy says, "You know, Al, why those people are out there cheering you today?" He said, "No, why?" Kennedy said, "They think you're on their side against the oligarchs" meaning himself. But they had a personal relationship and the people felt up here that he was on their side. I remember many years later I went to a plateau on the other side of the Andes and you go to these dirt huts and mud huts where the people live and you go inside, there were would be two pictures on the wall torn out of old newspaper, Pope John and John Kennedy. And Bobby had the same kind of reception when he went down there. And the same people hated him too. Bobby was a sharper personality, controversial. People who really disliked Jack Kennedy never would be able to say it, but with Bobby they wouldn't hesitate. Bobby was much more emotional and much more involved. Someone once said John Kennedy was a pragmatist masquerading as a romantic and Bobby Kennedy was a romantic masquerading as a pragmatist and that's not bad actually.

On the day that John F. Kennedy was inaugurated I was appointed Assistant Special Counsel. I never practiced a day of law in my life and haven't since. My very first task was to integrate the Coast Guard. We had been to the inaugural parade which went on forever. And as soon as it was over I rushed up to see my new office in the West Wing of the White House. I was coming down and I saw Kennedy coming down the corridor toward me. He said, "Dick, did you notice the Coast Guard detachment?" That was about an hour and a half ago and I had to search my memory. He said, "There wasn't a single black face. You've got to do something about that." So I went back up to my office. I didn't even know who ran the Coast Guard. I thought it was part of the Defense Department but it was part of the Treasury Department. So I called the Secretary of the Treasury Doug Dillon and told him what Kennedy had said. He said, "I'll get right on it" and within months we had integrated the Coast Guard. We actually did something. You don't often get that feeling even in the White House, you're passing these great laws but what happens on the ground with them, you're talking a very different thing.

You think of the '60s as the civil rights era and with Kennedy it started, slowly it started. By 1963 there were riots down in Alabama. The civil rights act of 1963 which ended segregation, legalized integration. There was real apartheid in parts of the South. It was not quite as maintained as South Africa. I went years later down in Mississippi with Jesse Jackson to campaign and we got into a fairly small town. We got to this small motel where we staying and there was a press corps with us. We walked in there and it struck me that only 10 years earlier if that same group had walked in there, there would have been riots. They would have surrounded the place with vigilantes. Now there wasn't anything.

The decade of the '60s starts with the defeat of Nixon and it ends with his being elected President. I didn't know him very well. I campaigned against him the whole time. He was a indefatigable worker. I remember once I was campaigning out in Minneapolis and he was there too. This was in the primary. I just saw him and I walked in to watch him. He sat there hours campaigning down to the last person. That was his whole life, he kept plugging away. He was a guy of single-minded determination. There were a lot of people just as talented as he was. But you always sensed there was a bad streak. I remember after Kennedy was elected we flew down to Palm Beach and Kennedy stopped to pay a courtesy call to Nixon somewhere. He came back about an hour or so later and he said, "Boy, I think we were lucky I won." Meaning boy, this was a bad guy. And he felt that. And Nixon demonstrated that when he got into office. He was probably the single most evil president we've ever had.

I was at the 1968 Democratic convention as part of the Massachusetts delegation pledged to Senator Eugene McCarthy. I had drafted a peace plank for Vietnam for the party platform until Johnson stepped in and prohibited the country from letting the people vote for it. Out on the streets of course it was later described as police riots, but all these young people were protesting and the police were forcibly arresting them. It was a terrible thing and the whole country saw that convention on national television. The convention itself was a political disaster and it just turned a lot of people off politics and it's never been turned back on since.

I was at the convention because at that point we weren't sure if Humphrey would get the nomination and very probably Nixon would get the nomination. I think Humphrey would have been better for us than Nixon. He was not in the Kennedy mold but not even the early Johnson. I did not feel at the time that I would hold on forever. I left politics soon after because I wanted to write but the promise and idealism hasn't come back. The '60s decade was sort of like the '30s. We were fighting the depression from the mid-30s up until '41 through '44. It was an era of people willing to sacrifice and idealism as well, and the '60s were like that. That kind of thing may come back but not under the present circumstances. You know we have this false prosperity. We think we're prosperous and the fact is, it is 20% of the people. The median family income in America hasn't gone up for a quarter of a century. Most people are not doing any better and haven't gotten any share in this national wealth. But, you know, they're eating. The fact is a big chunk of the middle class are totally left out. They're poorer than ever. When you say the median family income hasn't gone up that includes the fact that a hell of a lot more families are working longer hours and still they are not making any more. A male's salary has actually gone down so now you have to have two people working.

In the '60s we were trying to address these problems. What Clinton does is he says something about education and he wants more teachers and to combat crime he wants more cops out there, it sounds as if he is addressing the problem, but he is not addressing the problem that he hopes to solve. There is nothing done in any kind of magnitude. Most of the things we did was in various stages of the process which led to solve the problem, such as to eliminate poverty. This is certainly doable in a country as wealthy as this one. We tried to solve those problems and maybe we couldn't have. Maybe it was arrogant to even think it, but on the other hand, if you don't believe you can do something, you don't do anything. If you don't believe you can do something about the problems in the cities, nothing gets done. That arrogance is an absolutely essential ingredient of any progress at all.

I clerked for Felix Frankfurter. He took a really deep personal interest in me. He had no children of his own. He would stay around and talk with his law clerks. Once he asked me what I thought and I said I agreed with him. He said, "I don't get the best Harvard law clerks and pay them to come down here and agree with me. Tell me what's wrong with it." So I immediately, as all lawyers can, said what was wrong about it. He took me around Georgetown once when I first got there. He showed me where the cheap restaurants were where you could eat on a law clerk's salary. When I got home I realized this guy hadn't eaten in a cheap restaurant in 25 years. It was great working for him.

I did investigatory work on the quiz shows in the '60s. The movie ("Quiz Show") was based on the chapter in my book. I used to watch the quiz shows when I was in school. Everyone would gather around and watch these masterminds of the world answer these enormously complex questions. People won a lot of money. Several contestants won over $100,000. Now in today's dollars you have to use a multiple of 7 or 8 to find out what that would be, $700,000 or $800,000, and that was big money then. But it turned out I went to work for a House committee right after I left Frankfurter. You knew that something suspicious was going on. This committee discovered that a lot of these contestants had been rigged; they were given the answers. There was a huge fraud on the public. We held public hearings and they were rather spectacular. But it was interesting when I was working on the movie, we had a young scriptwriter. He said to me, "You mean people actually believed in these shows. I can't identify with that." I suddenly realized that this young guy was a child during Nixon and Watergate, he couldn't believe that people would find it so incredible. I was trying to think of something to compare it with, and I said, "Suppose you found out the Superbowl was fixed." He says, "Yea, I can see that."

I had a very good rapport with Charles Van Doren. I liked him. We got along well and I even understood why he lied to me all the time. In a sense he was kind of trapped. You get on one of these shows and they give you the answers and it looks like easy money, and the next thing you know, you're the most famous man in America. He was on the cover of Time magazine. How do you get out? It's not so easy to get out of that. But he could have gotten out quietly. Then afterwards he exploited it by going on television shows about it. You know we'd been through the McCarthy period. My feeling was that I had enough people willing to say they were rigged and bring out the facts about the quiz show. The real villains, the ones that made big money, were not the contestants but the sponsors and the network. I had no desire to get the contestants exposed. A lot of them went unknown since then. Especially having gone through the McCarthy period where people were killed by exposure. So I didn't want to call Van Doren either, partly for that reason, but on the other hand, circumstances changed that. But I liked him and I was sorry that happened. I went to Frankfurter during that period. As soon as the investigation started that effectively ended all the quiz shows.

I wrote this speech for Bobby Kennedy who gave it in South Africa. "Each time a man stands up for an ideal, or acts to improve the lot of others, or strikes out against injustice, he sends forth a tiny ripple of hope and crossing each other from a million different centers of energy and daring, those ripples build a current that can sweep down the mightiest walls of oppression and injustice." This was in South Africa at the height of apartheid. The year was 1966.