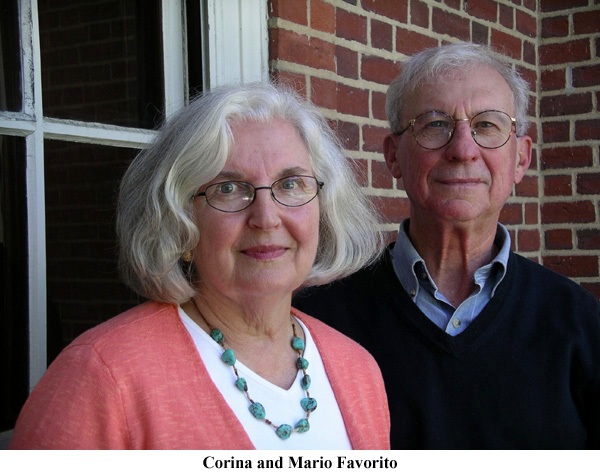

Mario Favorito

Interviewer: Michael Kline

Date: June 4, 2013

Place of Interview: Staff quarters of the lower library

Transcriptionist: Adept Word Management

Click here for audio. Audio file is in .mp3 format.

Michael Nobel Kline: 00:00:00.0 Hello, this is Michael Kline. I am here with Carrie Kline in the staff quarters of the lower library on the afternoon of June 4. Would you say your name for us?

Michael Nobel Kline: 00:00:00.0 Hello, this is Michael Kline. I am here with Carrie Kline in the staff quarters of the lower library on the afternoon of June 4. Would you say your name for us?

Mario Favorito: Okay, Mario Favorito.

MK: Would you say my name is…?

MF: My name is Mario Favorito.

MK: We never ask people their ages but maybe you could tell us your date of birth?

MF: April 16, 1938.

MK: Ok, tell us a little about your people and where you were raised.

MF: I was born in Brooklyn, New York. My mother was born in Brooklyn in 1909. Her father, my grandfather, arrived sometime in 1898 or thereabouts in Brooklyn. I spent my childhood and all of my years during which I was educated in Brooklyn. We did go across to Manhattan periodically but that was the city. I have to say I was pretty parochial because I didn't realize there was a world outside of Brooklyn until I graduated from law school and decided to leave New York. There was, you know, everything that we needed was in Brooklyn. I did, as a child, when you could travel all over the city for 5 cents, travel to museums in Manhattan. I learned how to ride in the saddle in Prospect Park in Brooklyn. I did travel far to Staten Island to ride horses every once in awhile or in Central Park. Essentially, I would say was Brooklyn-centric. When I graduated from law school, I decided to leave the city and go to Washington D.C.

MK: Well, wait a minute, before you leave—if I was--. If someone lowered in a helicopter in the middle of the night onto the streets of Brooklyn in the late 1930s, how would I have known I was there?

MF: It had no tall buildings except the Williamsburg Savings Bank. There were lots of trees and neighborhoods. It was quite different from the metropolis of Manhattan.

MK: Neighborhoods?

MF: Neighborhoods. I grew up in an Italian neighborhood. There were German oriented neighborhoods, Irish, Jewish in various places around.

MK: 00:03:11.4 And the Italian neighborhood was called?

MF: It was called South Brooklyn but today it has very fancy names. It has names like Carol Gardens, Cobble Hill, and it was essentially in an area that was close to the part of Brooklyn that overlooks Manhattan. It today is very, very fashionable. When I was growing up it was also fashionable but at a lower level. It was an area of brownstones. The brownstones were built in the late 1800s and were built by people with means who had come across from Manhattan on the Brooklyn Bridge. There were the Pierreponts and people like that. One of my neighbors—. Well he wasn't a neighbor at the time, but one of the houses was built by a person who was named Concella who was an editor and publisher of the Brooklyn Eagle, which was a wonderful newspaper which went out of business in, I think, the 70s.

MK: What sort of paper?

MF: I guess you would say progressive. When I was reading it, I was mostly interested in whatever local issues might arise but also the baseball. I really didn't have a focus so much on the editorial page at the time. But it was a great newspaper. The area that I grew up in was made up of lots of wonderful brownstones. They were mostly family owned. They hadn't been carved up into condos and whatever. Today, they're very, very expensive and people are carving them up into very expensive condos. My brother just sold his house there because he wanted to downsize and move closer to his family. We don't—I have a nephew who still lives in that neighborhood but not too many more people live there.

It's kind of odd, or interesting I should say that when both of my children were working in Manhattan, they ended up living in the same neighborhood where I grew up because that's where their grandmother and grandfather were. When they were little kids, we would visit and so they gravitated back there. It was kind of interesting that they basically went back to the old neighborhood. My daughter, my younger daughter Laura mentioned to me that after my mother and father had passed away and she went down to register to vote, the registrar said, "Oh, you are one of the Favoritos. You're okay. It's okay. You can vote." We chuckled about it. It was a very nice neighborhood when I was growing up there and it is still a very nice neighborhood.

MK: Did you have—were there neighborhood gangs, would be too strong a word but—

MF: We had a few toughs but there weren't really street gangs where we were. There were basically some wise kids and I, of course, I held my ground. I remember a couple of times where close by there was a police station that had a Police Athletic League group where children could play basketball or whatever. I remember there was a pool table that we would all gravitate to and play at. I was dutifully in line, waiting to play my turn and I remember this fellow sort of bullied himself in front of me. I was very polite, saying that, "I was here first. You have to get in line." He started to push me so I turned around and I whacked him in the nose so he got back there. I stayed in line. There was just that kind of stuff. There wasn't anything that you hear about today or in other neighborhoods. It was just—the usual stuff. We had a couple of boys but that was about it.

I have to say there are a couple of instances where—. I used to walk. That is one thing you did in the city. You walked everywhere. I walked to grammar school. I walked to high school. I walked to college. I walked to law school. It was all within walking distance of my house. Some of the walks were a mile and a half, maybe 2. It wasn't a big problem. I would walk all the way to Prospect Park. You would walk all over the place. I enjoyed it. I walked over the Brooklyn Bridge. It was very enjoyable. Every once in a while when you were walking to a certain neighborhood, you could get harassed a little bit but it wasn't—nothing to worry about.

MK: 00:08:52.9 So the law school was—?

MF: St. John's University School of Law. At the time, the law school was in downtown Brooklyn. Since—. I guess the year I graduated they moved out to a campus out in Queens at the Hillcrest Campus. Everything now is out in Queens County. When I was growing up everything was within walking distance of my house. My mother was a seamstress, my father worked for the telephone company, we didn't have a lot of means but as Carina mentioned with her family, my parents said, "You will get an education." It was an expectation and that's what you did. My brother became a lawyer as well. People in my apartment house—. We lived in an apartment house, we had several physicians that grew up in the apartment house. We just, you know, you would go to school. We had a couple of bad apples too but the expectation was there. You will get an education.

That education was in a sense, generic. College was generic. It wasn't Harvard or Yale it was, "You're going to go to college." That is what we did. Good people with good expectations and all hard working. It was not unusual. It's a common story. I do recall that I always had a part time job. It was always an expectation that we would also earn a little money to take care of our needs, so I always did that. I worked for Liberty Mutual Insurance Company. I worked for White Weld, which was a securities firm in lower Manhattan. I actually learned how to fill out tax returns for people because my father had a friend who was a person who had a travel agency and was an accountant. He needed help so I learned how to make out people's tax returns and made a few dollars doing that as well. I was sort of a. Whatever needed to be done, I was a good learner. It was—. I didn't think I was doing anything special, it was just what you did.

I went ahead—. And I always had activities, whether it was working or playing stickball or any of the other games in the neighborhood. We had lots of friends. Some of them we went horseback riding with and others we went to the beach. It was quite a network. I have to say, they were pretty much all male. (laughs) It was a little segregated in a lot of ways.

MK: This was an Italian immigrant neighborhood?

MF: Yes, if I remember the history, the neighborhood—. This south Brooklyn neighborhood at one point was the largest Italian immigrant community in the United States. It was huge. I am not sure what it is today but—. And so, families looked out for one another. There was always someone at the window, watching where you went, when you came home, what you did. (laughs) It was kind of like one big, extended family. The local church, there were lots of churches.

Carina Favorito: 00:13:03.3 Did you go to parochial school?

MF: I did go to parochial school. In fact, I have to say all my education was Catholic based. It was the grammar school, the high school, St Francis College, and St John's University. Although—it was kind of interesting—although it was also very open. When you were a small kid in grammer school, everyone had a catechism class, but beyond that it was just what I would describe as a professional education. We went through all the subjects and I don't recall being limited in any way.

CF: So it included religious education?

MF: It did. Certainly in grammar school it did. In high school, I think once a month you were required to go to Mass, go to church. In college, I don't think there was that much pressure and certainly not in law school. The law school that I went into, which was St John's University School of Law, originally started out as a law school that was an independent law school. My memory of the history is that in the late 1920s, somewhere in there, there was a group of lawyers who lamented the fact that lawyers, that law schools of the day were not admitting people who were women, Jewish, Italian, whatever and they really wanted to open that up. They started St John's University School of—well, St. John's Law school at the time--for the purpose of providing for legal education to those people from families who were basically, in their view, excluded from legal education. They established the law school and then sought affiliation with St. John's University, which was a Catholic university and still is, with the idea that they would run it affiliated with the law school but basically be independent within that structure. That went on for 30 years, maybe 20 years, and then it was finally integrated into the University. But it's fairly independent, in any event. It was interesting start to the law school. We had philosophy—. There was a philosophy class, but that was—that's what I remember.

CF: Did you have extracurricular activities there? Sports and things like that?

MF: Well, my extracurricular activity was the law review. I was—. When I got admitted to the law school—. It was kind of interesting, I got admitted by the skin of my teeth. I wasn't that great on some of these tests, but lo and behold, the first semester I ended up being 6th in the class and got an offer to join the Law Review on a scholarship. So I marched on from there.

CF: When you were in high school, you ran track.

MF: Oh, well in high school? I got my varsity track letter in my sophomore year. I was editor of the high school newspaper. It's where I decided, for no particular reason, to become a lawyer. I thought I was either going to become an architect or an engineer, electrical engineer, and then I ran into trigonometry and got the first C in my life. It was sort of a harbinger that maybe engineering wasn't going to be cut out for me. This was in high school. I did the sports and whatever and then we had public speaking—. To make a long story short, I won couple of awards, a couple of oratorical contests. Someone said, "Yeah, you ought to be a lawyer." Guess what? (laughs) I'm a lawyer.

CF: Don't forget about Jackie Robinson.

MF: Jackie Robinson, yes. My uncle was a butcher. He was a New York Giants fan. Butchers in those days were—had access to tickets to baseball games and other things. Even though my uncle was a fan of the New York Giants, whose home base was up in Manhattan on Coogan's Bluff, one day he called my mother and said, "I want to take Mario to a baseball game. It's at night, but don't worry, I will take care of him. It's important." My mother said, "Sure, you can take him." So we went. It was 1947 and Jackie Robinson was playing first base. It was his first season, and it was the spring. They were playing the Pirates. I was one of the few kids at 9-years-old to see Jackie Robinson and the whole team. He—I remember him saying, "It's important. This is important." So we went. Brooklyn was a wonderful place and probably still is.

MK: Would you have known you were in an Italian neighborhood if you had been dropped in there?

MF: Oh, yes. There were Italian pastry shops. There were Italian restaurants. The answer is yes. You would. You would have known. That was—. Because there were many different neighborhoods. You would go from one neighborhood to another and it was nothing—. When you were growing up, it didn't seem remarkable at all. You knew, if you were coming from Manhattan that this was an Italian neighborhood.

For example, there were religious feasts, especially in the Fall. Streets would get blocked off for block parties. There would be stages that would be up on stilts above the sidewalks where bands would be playing, singers would be singing, and it was just one big festival. We had several of those a year. Kids had fun. We had fun. People ate sausages and whatever. The music went on until midnight and then everything sort of stopped. It was usually a 3-day affair. These were run by the religious societies of the various churches. It was part of growing up in that neighborhood. Of course, being part of the community, it didn't seem odd to me at all. It was just what you did.

Everybody—. It was extended family. Everybody was friendly. People went in and out of one's houses with not a care. It was just everybody was welcomed. When I was a kid, one of my neighbors had the first TV sets and guess where all the kids went. (laughs) We were sitting there watching, I forget what it was, Howdy Doody or whatever.

MK: 00:21:17.2 Followed by Dragnet.

MF: Dragnet, that's right! (laughs) I enjoyed watching the early television, mostly the news programs of 19—I think it was the '52 convention when Eisenhower/Stevenson— . I forget, but I remember watching those conventions that first came on. It was very interesting to me. I didn't watch a whole lot of other stuff, but I like news.

MK: So what was your path to Concord?

MF: Well, it was kind of easy in a sense. When I met Corina in Washington, we decided that we wanted to move back—. She wanted to move back to New England. She didn't particularly think it was a good idea to move back to New York City so I said, "New England sounds okay."

CF: Where were you working?

MF: I ended up in the Austin Navy General Counsel in Washington. I went from there to United Aircraft Corporation in Hartford. Then I decided to look around for another position, and Corina helped me find an ad that brought me to a job as counsel for W.R. Grace & Co. which was headquartered in Cambridge. So we moved and we needed to find a place to stay, to call home, and I made, I guess, an executive decision. I wasn't—. From what I had heard, I was never going to drive on 128, and since I was in Cambridge, I was going to go out Route 2 and we were going to live either in Arlington, Lexington, Lincoln, Concord, or maybe Acton, but that was it. I had some friends at the office who lived in Concord. We came out. We looked for places in the snow. It was February. It was just unbelievable. We found a house in Concord and also I understood that the schools were superb. So, location, superb schools—here we are. Very simple.

CF: We skipped the Cuban Missile Crisis.

MF: Well, I was in the middle of the Cuban Missile Crisis in Washington D.C. at the time. This was before that, in October. My memory as a Navy lawyer at the Austin Navy General Counsel was that—. I was because of my civilian rank, I was a civilian lawyer. I was given a military rank of Lieutenant Commander just in case. Then I would be made an instant Lieutenant Commander, which was kind of odd because at the time I don't think I was more than 26. The plan was that if things were really bad, I would be airlifted out to Southern Virginia and help the troops requisition whatever they needed to requisition and they needed a lawyer so that was going to be my duty station. I remember having a briefing during the Cuban Missile Crisis by the officer in charge. He very well explained to us that, in case of nuclear attack, what would happen is that there were a group of people—the higher ups would be airlifted out and we would be in the second wave of exodus from Washington D.C. I remember one of my lawyer friends saying to this officer, "And pray tell, how many of us do you think will still be here when you are ready for the second exodus?" (laughs)

It never happened but it was an interesting time. Corina had, was living in an apartment house with children and families from the Russian Embassy and she was convinced there was going to be no attack because the children--. The women were still washing clothes in the laundromat in the basement and the children were still going to school. Given that, she figured out there was never going to be an attack because otherwise the kids wouldn't be here. (laughs)

CF: 00:26:08.9 I was in the elevator with the Russian Diplomats that morning of the President's speech and I didn't realize that they were Russian. The car from the Embassy came to pick them up, they all shook hands, and then after they got into a car, all these little children with red bows on their arms came out and got into another car. As they went down Connecticut Avenue, I saw them all going into the Russian Embassy. This was the morning after President Kennedy's speech about the blockade. Everyone at the office was very frightened. One man left and said he was taking his children and going to Maine. I kept saying, "But the children are still there. I can't believe that Christoff would bomb Washington if all the children are still there, going to school at the Embassy. That was my big—. The whole country was frightened and I am still saying, "But the children are still here!" I guess I was the calmest person around because I was convinced that everything was going to be all right. Maybe that was very naïve of me but—.

MK: It may have been but you had good instincts.

MF: Yes, for sure. At any rate, we lived through that and it was still a very good time. Obviously, I was there when President Kennedy was shot and I was in the main Navy building, which is where my office was. After the news came in, in the main Navy building, you could hear a pin drop. It was total silence. I remember walking the halls and hardly anyone spoke. It was just a somber moment, a somber moment. So, where am I?

MK: We are trying to get you up here to Concord and you have looked around and decided where you want to live.

CF: It's snowy.

MF: It's snowy. Well, here I am. Again, the reason we came here was because of the reputation of the town, the education, and its proximity to my job. It was kind of interesting, when we got here, having grown up in the city, I found that the town meeting form of government, the volunteerism was all very interesting. I said, "Gee, this is unbelievable." We had a system, and we still have a system where if you are interested in serving on town government, you can make out a green card with your name and what you would like to do. You put the green card in, so I did. I couldn't believe as a kid from Brooklyn that you actually could have—. There actually was a way in which you could actually participate in your local government to make things happen. I found that was very unique. So I put my green card in.

CF: 00:29:07.4 (???) (inaudible)

MF: 00:29:10.8 Oh, that was later on. At any rate, in 19—let's see—we were here in 72 or 73, I got a call from the town manager, Paul Flynn. He said, "I'm looking at your green card and it says here you have some background in transportation." I said, "Yeah, I do." Because when I was at United Aircraft, one of my legal projects was to be involved in the program to develop high-speed rail along the corridor from Boston to Washington. They were doing that in the 60s what they're still trying to do today. That is another story. He said, "We have this new committee that we are going to have to populate called the Bus Transportation Committee. Would you be interested?" I said, "Sure." I went down and talked with Paul. I talked with Phoebe Hamm who was the chair of the committee, and a few other people. My job was to establish the Bus Transportation Committee. I did some research and—.

MK: Did he ask you to chair it?

MF: No, I think Phebe Hamm chaired it. I don't like to chair things. I am a doer. So, Phebe chaired it. What I found out was, ok, the town—. The school department has the buses, the town has a need, and so we decided we would use the buses during the time they weren't bussing kids, which would be between 10:00 a.m. and 2:00. So I drafted a contract between the town and the school committee to allow the town to use the buses because we needed to have a contractual document. I hauled myself down to the Massachusetts Transportation Authority to learn a little bit about what you had to do to run a bus service. They immediately told me that if it was service where you charge money then the bus drivers had to be of a certain salary range. There were all these rules and regulations and it just looked like it would take it forever to get it done. I went back and I said, "My recommendation is that we do it as a free bus service. That way we avoid these regulations. The town said, "That's fine."

The town had a budget authorized by town meeting, which paid for the use of the buses and the drivers. We established routes. It was Monday, Wednesday, and Friday to do what Corina had indicated. And we were off to the races. It worked very, very well and went on for quite a number of years. When we—and we had a few issues. I think one of the years there was a fuel crisis. I don't know if it was '73 or '74 we had—. We found a way to—. The town had fuel so we used the town's fuel and reimbursed the town for the fuel. Once the program and the project got going—it was—I said, "Okay, there is nothing more that I can do. The people can run it now that it's established." So I said, "Goodbye." Phebe said, "How about Corina fill in where you—." (laughs) So Corina became one of my successors in the bus transportation committee.

When the bicentennial of 1975 came, we were planning for that. Because I had been on the Bus Transportation Committee and knew something about transportation, I was asked to join the Transportation Subcommittee of the Bicentennial Committee. It's a mouthful. The purpose there was to organize routes for people to come into town, to get out of town, make sure we knew where all of the marchers from Sudberry where their uniforms could come in, where we would park the cars. Because there was a Presidential visit that was going to happen, we had to also plan for where the Presidential motorcade was going to come, where they were going to park, where the buses were going to park. The most direct route to the operating room at Emerson hospital, God forbid something would happen, so we had to deal with that. I remember that we had a visitation from the representative of the Secret Service, in which we informed them that all those people dressed up in the colonial clothes actually had guns and were going to shoot them off. They said, "They are?" (laughs) But we got through that. So it took a couple of years of planning. It was all fun. I met a lot of interesting people and did that job and it was good.

CF: 00:34:51.2 You did other things.

MF: Huh?

CF: You did more important things.

MF: Well, subsequent to that, someone thought that maybe I might be useful on the Planning Board so I was asked to become a member of the Planning Board. I said, "Sure," so that was 6 years on planning. Subsequent to that, someone said, "You know all about zoning. How about being a member of the Board of Zoning Appeals?" I said, "Sure, I'll do that." That is one of my troubles. I don't know how to say no. I love the town. It's a wonderful town. You go around the country and you compare it to what we have here and it just—. What I want to do is to help out any way that I can. It's just a great community with lots of good, talented people. It's—. In a lot of ways it's a meritocracy at its finest form. It doesn't make any difference where you have come from. If you come from Brooklyn or whatever, if you want to help and you have some talent, you have a job. It's all volunteer. Nobody gets paid. The town could not run without volunteers.

I have been asked to do some other things. I was on an ad hoc committee to select the Town Manager, an ad hoc committee to select the Town Council. Then I was appointed in 1995, someone asked me if—They took me to breakfast and I should have known that was a bad sign. They asked me if—would I like to be a trustee and I—

MK: Of the--?

MF: Of the library. The Concord Free Public Library Corporation. I said, "Yes." In the library, the way things work in Concord is that the corporation, which is a nonprofit corporation, established by act of the legislature in 1873 actually owns the library. The buildings and whatever—then there's a partnership with the town. The town funds all of the staff and pays for the utilities. It's really a classic partnership between a private group and the town. We—. People love the library in this town and they contribute untold amount of funds to the library by contributions, bequests, and whatever. We are able with the endowment to pay for all the costs involved in renovating the structures, making sure they stay in good repair, the plantings, the groundkeeping, and all of that.

I did a back of the envelope calculation sometime ago and if you say the library is a joint partnership between the town and the independent library corporation, there's a total expense involved in providing the library to the Concord community. The library corporation through the munificence of its citizens actually provides 40% of the support of the library. But we couldn't do it without people who love the library. The story that I tell about myself is that when I was in high school, my high school teacher required that we read a lot of—not a lot but a good bit of-- Emerson's work and also of Thoreau's work. He was really a super guy. I have to say this—this is sacrilegious but I hated Emerson. My reward was to become a trustee of the Concord Free Public Library who has to manage all of Emerson's works. (laughs) So I am learning to like Emerson.

My story is not complicated at all. I liked the idea of volunteering. It's a great town. It's wonderful to be able to contribute in whatever way you can and I keep doing it.

MK: 00:39:38.4 Well your spirit of volunteerism is exceeded only by your humility about your own accomplishments. I can tell that right off the bat.

MF: I just—

MK: And I know how much this—I have already heard how much this town appreciates both of you and the amazing contributions that you have made. You certainly got the gist of the place quickly and jumped right into it.

MF: You mean I actually can affect what goes on here? (laughs)

MK: I thank you both very, very much.

CF: It was our pleasure.

00:40:10.3 (end of audio)

Back to the Oral History Program Collection page

Back to Finding Aids page

Back to Special Collections page

Home