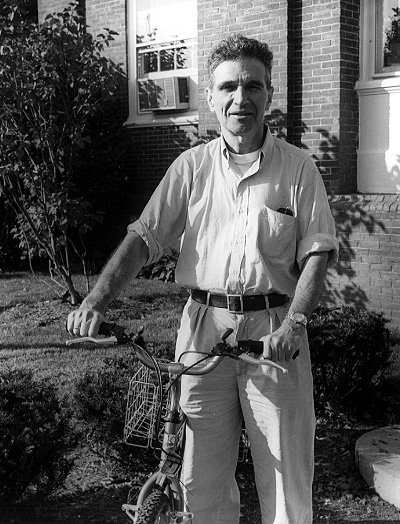

Dr. Robert Coles

Age 66

Transcription sponsored by The Federal Savings Bank of Concord, Sudbury Road

Eyewitness to History: Civil Rights Retrospect

Dr. Robert Coles, born September 1929, began his work in the South as an Air Force physician in

1958 in Mississippi at a time when the civil rights movement was gaining momentum -- a tumultuous

time, a time of important political and social change. As a child psychiatrist, he was able to study the

impact of this significant and critical period on children, and inevitably the adults who he says, "nurture

them, teach them, and on occasion, fail them miserably." A social historian, a prolific author, on the

staff at Harvard Medical School, he has given a voice to those who are often rendered invisible. The

first in his Children of Crisis series is a study of integration in the South. His series went on to win a

Pulitzer prize. We draw now from Dr. Coles' address to the graduating class of 1994 at Concord-

Carlisle High School and his retrospect of the civil rights era.

Dr. Robert Coles, born September 1929, began his work in the South as an Air Force physician in

1958 in Mississippi at a time when the civil rights movement was gaining momentum -- a tumultuous

time, a time of important political and social change. As a child psychiatrist, he was able to study the

impact of this significant and critical period on children, and inevitably the adults who he says, "nurture

them, teach them, and on occasion, fail them miserably." A social historian, a prolific author, on the

staff at Harvard Medical School, he has given a voice to those who are often rendered invisible. The

first in his Children of Crisis series is a study of integration in the South. His series went on to win a

Pulitzer prize. We draw now from Dr. Coles' address to the graduating class of 1994 at Concord-

Carlisle High School and his retrospect of the civil rights era.

I want to tell you a story that takes me back in time to the tumultuous 1960s. At the time I happened to be a young doctor and was drafted as all doctors were to go into military service for two years under a special law that took us in. I happened to be in Mississippi in charge of an Air Force psychiatric hospital when the whole civil rights movement exploded before this nation. I was then studying school desegregation as it took place in the South. I stumbled into it by suddenly before my eyes, witnessing a little girl of 6 trying to make her way into an elementary school in New Orleans. I was on my way to a medical meeting at Tulane Medical School. I never got there because the whole city of New Orleans was in an uproar. Thousands of people assembled before an American school building in order to prevent this little girl from going into that school. All because her skin color was black. They shouted and screamed, and the entire school was boycotted by the white population. I would one day find out that this little girl took it upon herself to pray hard and long for the people who wanted to kill her, calling upon words that many of you have heard in churches. The words she summoned in her prayers for those who would kill her were "Please, God, try to forgive these people because they just don't know what they are doing."

Later, I went up to Atlanta where ten high schoolers, black, integrated four high schools. I got to know those ten young men and women rather well, and particularly well, a young man who was a senior at Henry Grady High School. Henry Grady High School then was not much different from Concord-Carlisle HighSchool - a relative prosperous neighborhood of Atlanta to which came people hoping for an education and for advancement in life. This young man, Lawrence Jefferson, was one of two blacks in Henry Grady High School. This was a momentous time in Atlanta. The civil rights movement was well on its way, and young people were coming from all over the country to the South to try to work on behalf of those who could not even vote in this country. That is only thirty plus years ago -- could not even vote in the world's greatest democracy.

I went to a basketball game with Lawrence in the spring of his graduating year. It was the first athletic activity that the school committee allowed in that particular school. They were afraid of violence, and there was plenty of reason for them to be afraid of violence. We came into the gym, not unlike that gym, and sat down up front because Lawrence wanted to see a basketball game close. We sat down and soon enough spit balls started arriving in front of us and sometimes upon us. Then bottles landed, some of them breaking, and we began to hear language that wasn't particularly friendly. Paper planes descended and the language was assembled into longer and more threatening sentences. Finally I turned to this young man and I said "Let's get out of here." He looked at me and said "No." I said a moment later, "Let's get out of here." He looked at me and again said "No."

Then I thought to myself mobilizing all the psychiatric thinking that people like me have sometimes not necessarily a blessing, I thought to myself he's frightened. How can I help him to be less frightened? Then I decided that the issue was not to help him to be less frightened, but as I had already said, to get out of there particularly because a bottle or two had landed on me and on him. So I grabbed him and I said, "Lawrence, we're going." That's what they call brief psychotherapy. I pulled at him and he resisted and he said, "You go, I'm staying." I said, "Lawrence, I think we both better get out here fast" and he said, "You go." Then I thought a compromise is in order and I pointed to the exit sign way up in the back. I said, "Let's go and sit up there, Lawrence. We'll get a better view of the game." He said, "I think we'll get a better view of the game here." Then the police arrived in large numbers. They surrounded us, and we sat and watched the game.

When the game was over, I drove him home. His father worked as a janitor in an apartment house in downtown Atlanta and they lived in the basement of that building. I went inside and I thought I had better have a talk with this young man. I better find out what was happening to him. That's my job, I'm interested in this. So we started talking and I said, "Lawrence, that was quite a time we had."

He said, "We won."

I said, "I mean before the game."

He said, "Not particularly."

I said, "Pretty scary there for a while."

And again he said, "Not particularly."

I said, "Really scary there for a while."

nd he said, "Not particularly." A refrain -- not particularly.

I thought to myself I know how to get him to talk more willing and extensively about himself. I looked at him and I said, "It was very scary, Lawrence." He said nothing and then I thought in a moment of generosity, if not noblesse oblige, which is a hazard for people like me all too often. I looked at him and I said, "Lawrence, I'll tell you something. I was really scared."

He looked back at me and said, "I know you were."

I looked at him and I said, "And how about you?"

Then he repeated, "Not particularly."

I thought to myself he needs analysis. This will take time. But ever hopeful, I did what people like me do, one wonderful critic referring to Walker Percy's novel "The Movie Goer," applauded it for not resorting to what the critic called the mannerisms of the clinic. Well, I resorted to the mannerisms of the clinic. I started asking this young man whether he really was as afraid after all. And he suddenly slipped into a childhood story. He said, "You know, I remember when my mother took me to see Santa Claus at Rich's" which is the equivalent to Jordan's or Filene's.

I said, "You do?"

He said, "Yes, I remember we were standing in line trying to see Santa Claus and I guess I stepped on the toes of this girl who was in front of me, and her mother turned around and got really angry at my mother, and she warned her that if I did that again, there was going to be real trouble. That girl was white and so was her mother." He also said, "My mother took me home. I never saw Santa Claus. She took me home, and she gave me a beating and I still remember it. It was terrible pain." Then he looked at me and he said "Tonight, it was sweet pain, sweet pain."

I said, "What do you mean by sweet pain?"

He said, "Doc, tonight I wouldn't have left that place as long as I could stand up because I had something to do there and I was going to do it."

Now the interesting thing to me as I thought about that evening, and I've given it a lot of thought over the years, is that it has implications not only for Lawrence but for all of us. The interesting thing about that evening is I could have left that game, wanted to leave that game, had nothing to lose for leaving that game, and he had everything to gain by staying there and seeing that game, police or no police. What he had told me is that for me what was a moment of fear and dread and anxiety, for him was a moment of opportunity, indeed a moment of achievement. We may have been sitting side by side, we have been friends, we may have come to the game together and left the game together, but we brought to that game our different lives. And those lives had different consequences for our behavior, for our aspirations, for what we wanted to do, and that shared moment of time in a high school building located in the United States of America in the second half of the 20th century which all of us have inhabited. What for me was a mere moment of athletic observance with a friend and maybe part of a research project, for him was everything.

He would tell me about his mother's and his father's memories. They were born in a small town in South Carolina, and his mother remembered having to get off the sidewalk when other people of different color walked down in front of them. His mother remembered as Billie Holiday sings in that song, "strange fruit," his mother remembered a body dangling from a tree. I should tell you that in this century under the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt, a great American president, it was impossible to get through the United States Senate in 1937 an anti-lynching bill. In the 20th century under a progressive American president, under the New Deal even, it was impossible to get an anti-lynching bill through the United States Senate. That is the kind of history this young man Lawrence knew, not only in his head, but in his bones, in his heart, in his soul, and that was the kind of history he was teaching me, for all of my education. He was teaching me really about character and how important character is. How we live our life and what we ought to believe in, and believe in enough to live by it, and to be ready even to suffer for it.

Now let us come back to Concord, Massachusetts. One hundred fifty plus years ago, from this town, a man went into Cambridge to give an address to a lot of big shot people in a well known American university where modesty doesn't always reign. It would be known as the American Scholar address. In that address Ralph Waldo Emerson made a distinction that I want to leave you with, the distinction between character and intellect. Character, he said, matters much more, is higher, is the way he put it, than intellect.

Sure it is important to get grades, but let us remember what Walker Percy said, if I may mention him again, in his wonderful novel, "The Second Coming," he described one of the characters as "one of those people who got all A's but flunked ordinary living." Let us try for A's in ordinary living as Emerson reminded us. That is what really matters, to find some purpose in life and to live for it, to be tested by one's ideals, and the crucible of everyday experience. Sure it matters, these grades, these numbers from these SAT scores, although I'm waiting for the research project that will help us to figure out who these people are who make up those SAT questions. What kind of minds do they have, and where are the studies that tell us about this kind of thinking as a test of our worth?

Let us test ourselves and our worth by our everyday deeds and let us find those deeds and live with them. Let us step out of ourselves and into the shoes of others as Lawrence was trying to tell me I should try to do. This is a big moment in your lives -- to get out of here, to go someplace else. These exits, these entrances keep on accumulating until finally there is the last exit. It's wonderful to be alive, to have a beautiful day like this gracing us, and it's wonderful to live in a town like this under circumstances like these, in this great country flawed as it has been and as it still is, nevertheless, this great country. I pray and I hope for you that you will have the chance to make this even a greater country because it is your country, and this time is yours, and these years ahead are yours. Help us to be a better country. Help us to be more charitable and generous toward one another. Give of yourselves toward one another.

Dr. Coles began the book Children of Crisis: A Study of Courage and Fear, published in 1964, about black and white children involved in school desegration, with the story of Ruby Bridges. Thirty- five years had past since they met on November 14, 1960, while parents boycotted Frantz School in the working class ninth ward of New Orleans, and screamed threats at Ruby Bridges as federal marshals escorted her into the building.

Norman Rockwell painted this scene and John Steinbeck wrote about it in Travels With Charley. "My life has never been the same since I stumbled into her," said Coles. "I was just thunderstruck by that mob and her stoic dignity, and so I went back and watched it again and again. She is my touchstone, because if I hadn't seen her and seen what happened, I would have gone on and never gotten involved."

In June 1995 Dr. Coles was awarded an honorary degree from Connecticut College. As he did at Concord-Carlisle High School, Coles cited the moral courage of Ruby Bridges integrating her elementary school. College President Claire Gaudiani made the decision to invite them both at the beginning of the school year and awarded "just Ruby" with an honorary degree as well. Today she is Ruby Bridges Hall, with two children of her own. Though she was alone at school, she describes the strength she drew from community support. "When I integrated the school system, people were there for me, for my parents. There were neighbors and friends who dressed me and walked with me. The whole neighborhood got involved. But somewhere we lost that."

Back to the Oral History Program Collection page

Back to Finding Aids page

Back to Special Collections page

Home