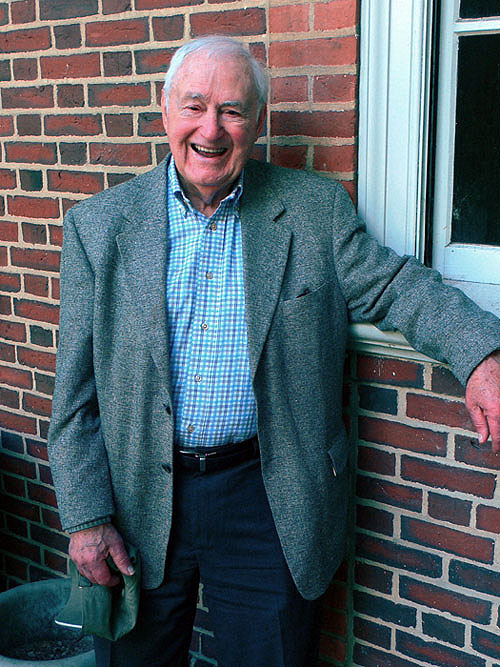

Robert Carter

"You meet a lot of people in the retail furniture business …"

Interviewer: Michael Nobel Kline

Date: 5-25-10

Place of Interview: Concord Free Public Library

Transcriptionist: Carrie N. Kline

Click here for audio, part 1

Click here for audio, part 2

Audio files are in .mp3 format.

Robert Carter: And she was also a librarian. She was the cataloger here at the library. And she worked at my business for a while. She was invited by the Antiquarian Society to speak about genealogy. And she spent a long time getting her copious notes together. And when she arrived at the museum down here on Lexington Road, she discovered she had left her notes at home. But the audience told her afterwards that it was a wonderful presentation, and she was so glad that she had left her notes at home, because it probably would've spoiled it.

Robert Carter: And she was also a librarian. She was the cataloger here at the library. And she worked at my business for a while. She was invited by the Antiquarian Society to speak about genealogy. And she spent a long time getting her copious notes together. And when she arrived at the museum down here on Lexington Road, she discovered she had left her notes at home. But the audience told her afterwards that it was a wonderful presentation, and she was so glad that she had left her notes at home, because it probably would've spoiled it.

Michael Kline: Yeah. Yup.

RC: So.

MK: Would you please say--. Well first of all, we are Michael and Carrie Kline here at the Concord Free Public Library, continuing this series of interviews. And it's the 25th of May, at 3:00 o'clock in the afternoon, a perfectly beautiful afternoon. And would you please say, "My name is," and tell us your name.

RC: Robert L. Carter.

MK: Could you say, "My name is R--?"

RC: My name is Robert L. Carter.

MK: And we never ask people their age, but perhaps you'd tell us your date of birth, so we can put--.

RC: Yeah. June 28th, 1922.

MK: Twenty-two.

RC: I'll be eighty-eight the twenty-eighth of the next month.

MK: You would've had me fooled.

RC: No.

MK: Yes.

RC: [laughs]

MK: If you don't mind, would you start off and tell us about your people and where you were raised.

RC: I was born here in Concord on June 28th, 1922 at the New England Deaconess Hospital, here in Concord, Massachusetts. It later became Emerson Hospital. And I was born to Robert W. and Winfred French Carter. And I've lived here all my life, except for three years, two months and two days that I spent with the military during World War II. So, and I've only lived in three places here in town also. When I was born my folks were living at a house that was at the rotary at Routes 2 and 2A I think it is, in Concord. The house is no longer there. And then we moved to Highland Street. And then we moved to Hayward Mill Road. And I've been there for about fifty years now. So.

2:43

I went to the Concord public schools. I thought first I might speak to, I was going to dwell on telling you about the schools, because we certainly had an accumulation of the most interesting school teachers that any town ever had—

MK: Please.

RC: --in the United States. Well. Our first grade teacher was M. Elizabeth McKenna, also known as Daisy. And she was an interesting person. Her disciplinary procedures or actions were entirely different than anybody else's. If you misbehaved you were placed in Miss. McKenna's wastebasket, under her desk. And if that didn't cure you of what you had done, then next time you were probably had to stand behind the pull-down blackboards that covered the coat hooks where we hung our coats in the winter. And you couldn't see anybody or hear anything. And it was, you know, it was like being in the dungeon. And she didn't mind using a, the foot rule to give you a good whack as she made you run around the classroom if that's what she caught you doing if she wasn't there. And she's whack you as you went by her.

4:03

And we had another teacher--.They certainly didn't follow Mr. Alcott's teachings to the core, because--. They did some things, but this particular thing about discipline they didn't follow. Mr. Alcott, you know, required his students to discipline the teacher, which was very difficult for students to do, because they liked Mr. Alcott. Well that wasn't the way it was at, in the Concord Grammar School. The teacher really punished the pupil. I can remember Marion Frances Johnson, who was the Second/Third, double grade, school teacher, shaking a child, run down the aisle and grabbed the child out of her seat, or his seat. And she would shake the child. And you would be frightened to death as you saw her coming down the aisle that it might be you.

5:02

So that's some, my recollection of disciple at the Concord schools. They did follow all the innovations that Bronson Alcott introduced. They had music, art, physical education, and recess, as he introduced to the school system years ago. And one particular thing, music, was an item that really interested me, and I at one time thought I'd pursue a career of music, but I didn't. And we had a teacher by the name of Happy Reynolds. I don't know if that was her real first name or not, but that's what they called her. And she was the music supervisor. And every Friday during the winter months, we would go to the assembly hall and sit in the chairs. And on the platform was a Atwater Kent radio, and we would listen to the Walter Damrosch concerts. And Miss Reynolds had life size plaques of the various instruments, and as they were playing in the concert, she'd walk around the room and point to them: "Violin." Or, "Viola."Or, "Cornet," you know. And she walked around. And she looked like somebody out of, what's that famous opera? Oh, gosh.

Carrie Kline: Madame Butterfly?

RC: No.

CK: [laughs]

RC: [laughs] It's about a girl that worked in the tobacco factory. You know who I mean. And--.

MK: Carmen?

6:50

RC: Carmen. She looked like she was just finished a scene from Carmen. She wore her hair the same way with curls down to one side. All she needed was a rose in her mouth, and she would look like--. I don't know. Who was the female character in Carmen? I don't remember her name, but anyway, probably singing the Habanera or some other song. Ha ha!

And then for physical education we had a Mr. Howard Hawks whose son Bob was in my class in the high school. They came down from Maine, and we used to get a kick out of hearing Bob talk about seeing "bey-ahs," up in Maine. And we had never seen a bear of course down here in Concord. And his father was the physical education direction, as I say, for the boys. And during the good weather we'd walk all the way from the Harvey Wheeler West Concord School, down through the center of West Concord, onto the playground at Percy Rideout playground. Percy Rideout's sister was a teacher in the Concord school. She taught English in the high school. Percy was a casualty of World War I. And we'd play soccer. And we'd walk back. We'd be walking along the street, Bradford Street, where the Allen Chair Company was located. And there was always a very--. Well I wouldn't call it pleasant, rather a pungent odor, smell. A kid said it was banana oil, which of course it wasn't. It was some kind of a chemical that they use in the finishing of their products at Allen Chair Company.

MK: Lacquer of some kind?

8:37

RC: Lacquer. Yeah. And it had the smell like banana oil. That's what they. We were told that's what it was, but of course it wasn't. Anyway, and the girls, their director was Miss Clark. She was there for many years, long time director of the girls' physical education. And on rainy days I can recall that between the door jams there was a slot at each end, and the teacher would slide in a pole, like a closet pole, between the two door jams. And we would raise ourselves on that bar for exercise, on a rainy day, when we couldn't go out to play in the playground. So that's my story about--.

MK: Chin ups of some kind?

RC: Yeah, chin ups sort of thing, That's right.

MK: Umm hmm.

RC: Yeah. And. But the school was an extraordinarily different school. I often wondered how if happened to become built in Concord. It was very modern. It was kind of Spanish in style. Had a tile roof. And its unique characteristic was that each classroom had an exit to the outdoors, as well as one to a central hall. And in addition, I spoke about the pull-down blackboards that also covered the coat-hanging area. And each classroom had a glass in the ceiling. What do you call those?

MK: Skylight?

10:25

RC: Skylight. Yup. Each classroom had a skylight. And it had a, didn't have a full basement, but about half the basement was very nice, clean, beautiful monolithic pour of cement to make it nicely appearing. No rocks, no rock foundation like most of the houses had in the area. And we would use that area for exercise on a rainy day. It also was a place where the children who brought their lunches, who lived a mile or beyond the school, would be able to eat their lunches. They didn't serve lunches, but they would bring their own lunches and eat it there in this new basement. Well that's my story about schools.

MK: When was the school built, and is it still standing?

11:18

RC: Yes, it is. It's a community center now, Harvey Wheeler Community Center. It was built in 1917, and I think it opened the next year, 1918. And next to it, at the corner of Church and Main Streets was another kind of, sort of a Queen Anne-style wooden school, two stories, with an attic. And that was the, that was built in--. I have a note here of when it was built. [sound of paper shuffling] I won't tell you the wrong date, because I looked it up. 1886. And it remained until the early 1950s when it was destroyed. Now there is another wooden building on it for pre-schoolers, privately--. The building is privately-owned, but it's on town land, which is kind of an odd situation. And the whole area there where these two schools are, or were, belonged to a man by the name of--. What was his name? Ralph Warner. In fact that, the village itself was originally called Warnersville. He had a factory there, a--. He made buckets, that sort of thing, and he had dammed up the Nashoba Brook to create what is now Warner's Pond. And he used the power from that brook to run the machinery to make his pails. It was called a pail factory. In fact he--. I think he built the bridge over the connection of the brook to the Assebet River. And it was called Pail Factory Bridge. Still there. Still has a plaque on it, I believe, that identifies it as the Pail Factory Bridge.

13:27

So one thing that I notice from, probably the biggest change in the town is the size of it. When I was born there were about 6,000 people in both ends of town, out of which 1,000 were prisoners at the Reformatory. So that leaves about 5,000 residents. And they, I'm just guessing, but I imagine it was divided--. There were about 3,000 in Concord Center and 2,000 in what is now West Concord. And there were a lot of industry in that end of town. And they, the ones that were there when I was a child was the Boston Harness Company, Moore & Cram Webbing Manufacturing Company, the Bluine--. That's an interesting story. Conet Machine and Steel, Allen Chair Company, Concord Woodworking, W.M. McDonaldÆ’. That was an abattoir along the railroad tracks in the far western end of the town. American Cyanamid and Chemical Company, the Lambretta Garnett Mill. It was a foundry. It made machinery for the cotton-spinning business that--. I think their main office was up in Loconia, New Hampshire. And then there was the American Woolen Company. They occupied what we know as the Damon Mill. And the Whitney Coal and Grain Company. They're all gone.

15:08

Those are the industrial people. And then there a lot of--.

MK: Was it the--? Why was so much industry located--?

RC: The railroad. In fact we had four railroads that came through the town. There was the Fitchburg Division of the Boston and Maine, and the New York, New Haven and Hartford. It was called the Framingham and Lowell Railroad originally, but it became part of the New York, New Haven and Hartford. And that went from Framingham to Lowell. There was another railroad that came out form Boston through Lexington, Bedford, into Concord Center, and finally extended to the Reformatory, and that was the southern division of the Boston and Maine Railroad. And there was another one that, it had a strange name. It was called [sounds of paper shuffling and thinking vocalizations]. Oh. Very interesting. The Concord, Acton, Nashua and Montreal Railroad. And it went from West Concord, up through to Nashua. And I guess from there on it went on, it connected to Montreal. It connected with the Maine line to Canada. And there was also--. That was the four lines of the railroad. There was also two streetcar lines; one was the Concord, Mainard and Hudson, that provided transportation from Arlington to Clinton. And when you got to Hudson you could transfer to Marlboro. And in the other direction, the easterly direction, in Concord you could transfer to the Middlesex and Boston that went down Bedford Street to Bedford, and then from there into Arlington, and eventually into Boston. And those disappeared just a year before I was born, 1921. From about 1889, somewhere in there, until 1921 they operated. And after they deceased, along came a bus line called the Lovell Bus Line, and it ran from--.

CK: Called what?

RC: L-O-V-E-L-L. Lovell. They were white buses with a red stripe around them, and they operated from Arlington to Clinton. They had, they used the car barn in Maynard as their terminus for storage of their buses. And what else did they do? And then there was the Middlesex and Boston--.When they gave up their trolley cars they substituted with buses. So that line stayed in existence for a long time, way up until I think World War II.

18:24

Well, and then in the commercial line, in my childhood there were several—[blows nose, having arrived with a cold] Excuse me.—Grocery stores in West Concord. There was the Great Atlantic and Pacific, A&P, not a big store. There was O'Keefe's that later became the First National Store. And--.

MK: The less you can rattle this paper--. We're very interested in an absolutely pristine—

RC: Okay.

MK: --recording.

RC: So I'll be--

MK: Okay.

RC: --careful not to do that. Mr. Pike's Meat Market, Adams and Bridges General Store, Prendegast Market, Bennie Benson's Grocery Store, Bartelomeo's Fruit Store, and John Condon's Grocery Store. All those have disappeared.

19:11

Then had a place called Hogan's Bar where Mr. Hogan sold penny candy. Poor man, he spent hours waiting for kids to decide which penny candy they were going to buy. And we had two department stores. We had London's Department Store and Fritz's. And I recall both of them at Christmas time would employ somebody to be Santa Claus. And they would pass out bags of candy to all the kids who came. And that was fun. There were three barbershops, Mr. Telreault's, Mr. Mazzeo's and Mr. Lombardo's. And there was--. There were two poolrooms. There was Blodgett's and Mandrioli's. And there was a hardware store by the name of R.J. Rodday's.

MK: R.J.?

20:06

RC: Rodday. R-O-D-D-A-Y.

MK: Okay.

RC: And there was another store. It was called Loring and Fowler's Furniture Store. He carried some musical instruments, and he also had, when phonographs, the hand-powered phonograph, where you wound it up, you know. Remember those? And he later sold that store to my father, and it became Carter Furniture Company. And there was also, where a store is called today, Forever Tile, there was an eatery. It--. I don't know the name of it, but the daughter of the folks who owned it later on married a man named Comeau, and they lived upstairs in the apartment over the store. And there was another little eatery too. It was in the diner, and the diner was located on Church Street, next to the railroad tracks, just a little west of the gate tender's shanty there. And it was there for most of my early years. I don't know what happened to it, but it disappeared. And then we had a hotel that also had a very nice dining room. And in the professional area we had--.

CK: What was the name of the hotel?

RC: The Elmwood. E-L-M-W-O-O-D. The Elmwood Hotel. It's now--. I don't know if it's condominiums or apartments, one or the other, but it's still there.

21:47

And in the professional area we had a lawyer, Edward F. Laughlin, a doctor, Dr. Isaiah Pickard, P-I-C-K-A-R-D, and a dentist, Dr. Davis. He had a office in what was called The Association Hall Building. It was quite a large building. It had about three floors, one two three. Yeah. And the top floor was the Independent Order Odd Fellows meeting rooms and the Rebekahs. And in the second floor there was a large auditorium. And one thing I remember about that auditorium was when I was about nine years old, the West Concord Women's Club hired a traveling theatrical troupe to put on a play, a musical; it was called The College Flapper. And I--. It burned in my memory, I guess because one of our schoolteachers had a leading part. And you know what that did it for kids. We were breathless [?] to see what he was going to do. And I remember that there were two romantic episodes taking place in the play. One was a younger couple. The man was our schoolteacher, Mr. John B. Hendershot. I even remember his middle initial.

CK: Hender--?

RC: Hendershot. H-E-N-D-E-R-S-H-O-T. Hendershot. And his beau was a Mrs. Boyd. I can't think of her first name. But she sang a song, "Whatcha Sitting Over there For." "What's a cozy armchair made for? Whatcha sitting over there for? Let's get—Come over and get friendly." And then the older couple that were falling in love, Mr. Ben Goddard, who had been a schoolteacher in town, he was proposing to Cora MacLeod, a lady who lived up on Main Street. And she says, "I don't believe it, but say it again?" And then the chorus picks up that line into a song, and the dancing beauties of West Concord appeared in the stage and did a choreographed—Is that correct? Pretty close .—routine, kicking up their legs and dancing around on the stage. And that included Priscilla Pratt, Jeanette Christian, and Clara Fenton, the three of the girls that I remember, because they were a little older than me. And you know how young boys fall in love with older girls? So! Anyway, that was an interesting production. What else do I remember? I'm going to flip--.

MK: Go ahead and look through.

25:08

RC: Okay. Let's see. [sounds of paper shuffling] Oh, I spoke about education. I could tell you every classroom, who was the teacher back in my education at the Concord Public Schools. In that wooden building on the corner of Church and Main Streets, the Queen-Anne-style schoolhouse, in the basement there was a classroom for industrial arts, and a man by the name of LaForest Robins was the teacher. And on the first floor, there was a double grade, second and third. That's where this Miss Marion Francis Johnson taught. And across the hall--. It was a big, open hallway with a staircase that went up to the second floor, and Mrs. Gale. Her name was--. Her maiden name was Bean. And she was married to the brother-in-law of Mrs. Margaret Wetherby. And it's interesting, if you're looking back, of how these people were connected with the Reformatory. Mrs. Wetherby's father, Mr. Gale, he had been the superintendent of the Reformatory at one time. And I don't know where Miss Bean came from, but anyway, they, she fell in love with her, with Mr. Gale's son. And she taught the third grade. She taught us our mathematics' table. What is it?

MK: Multiplication.

RC: Multiplication table. That's right. And then on that same floor there was a large room. It was in--. It was the industrial art, the domestic arts room. And they taught sewing and cooking, and they had stoves in there that the girls would practice cooking whatever they had made. And it was--. You could smell the food cooking throughout the building. And there was another room that Miss Susie Wood, as English lady, she conducted a special class for the children who were a little bit slow.

27:35

And on the second floor, Miss Wilson taught the fourth grade, and Miss Hemple taught the sixth grade. And another sixth grade was taught by Miss Mary G. Hartnett. And I must tell about the--. While we were in that fourth grade, we were almost ten years old. It was a cold, windy March day, and we heard the fire whistle blow, announcing that there was a fire. And all of a sudden we were told that we wouldn't be allowed to leave the school unless our parents came to pick us up, because the Fire House was on fire, with the fire engines in it. And the fire spread to a boarding house that was next door and block of stores. And for a while, adjacent to this block of stores and the Fire House was the Catholic Church, and they thought it--. "Oh, the church is going to burn down." But the wind shifted, and it took the embers across Main Street, in a southerly direction, and set two houses on fire. One burned down completely, and the other one was badly damaged. And, as I say, finally, when they thought it was safe to release it, they let us leave school. By that time, the action was over. We--. All we could see were the charred ruins of this disastrous fire. So that was maybe 1932, March of 1932.

MK: Hmmf. What a story.

29:21

RC: Yeah. . . . I guess I've told you about everything that I had written down here, that I remember as a kid. Of course the big thing that was reviewed recently on television was the 1938 Hurricane. And I remember that vividly. I was home, as I am today, recovering from a cold. And all of a sudden, the back, what was, a screen door on the house blew off. And we thought that was strange. Didn't somebody remember to fasten it? And we looked out, and the trees were bending way over, a big oak tree across the street, uprooted and landed on the house. And all--.Then all of a sudden we were without electricity. We were without electricity for about a week. And as you looked down Highland Street, there were trees all across the street. And you couldn't drive up or down it; it was impossible. And, as the town's departments got out to clear the highways, you could see the devastation that that hurricane had caused. We didn't have the water surge that they had along the coast, but we certainly had the wind.

MK: Terrifying.

CK: What was that week like?

RC: Pardon?

CK: What do you remember about that week without electricity?

30:55

RC: Ah, it was kind of enjoyable. You couldn't listen to the radio. Of course we didn't have television. The telephone, in most cases, was still operative. As soon as somebody reattached the wire in through your house it--. If you didn't lose the power from the house to the telephone pole, you were in pretty good condition, because as soon as they were able to restore--. The first thing they restored was the telephone. And then one by one they worked on the houses for electricity. So it was a whole week. I liked it. I thought it was--. I thought it was an interesting experience. Got a little boring when you couldn't listen to your favorite radio programs, but--.

MK: Which were?

31:45

RC: Amos and Andy, the Lone Ranger, Mr. Keen, Tracer of Lost Persons, the Easy Aces. Do you remember them? And, oh, there--. Oh, Orphan Annie. There were a lot of them that I used to wa—listen to.

CK: So these weren't battery radios then?

RC: No. No, they were electric. Some--.

CK: You were very modern at fifteen. Yeah. We did. We all had--. Some people still had a battery-operated. And of course they were in good condition. They had radio all through the storm. But most of us lost that connection.

MK: Was there a certain bonding in the community over this tragedy? Did people kind of pull together in any way, any kind of way?

32:47

RC: I--. Yes, they did. Yup. One thing that I remember about it was they--. Of course the grocery stores, they lost their refrigeration. And my mother went to one of them—

I won't mention the name—and bought some hamburger, which she shouldn't have done. And I got tomane poisoning. And by then we had another doctor in town. His name was Dr. Burger. He lived next store to me, on Highland Street. And he sat with me during the night, feeding me tea, and which I was, returned to him! And eventually I got over it. But that was a casualty of that storm, that things weren't really a hundred percent under government control at that time.

33:43

And anyway, yes we were--. We became much more interested in our neighbors and their security and their, made sure that they had something to eat. And if--. Luckily, it was late September, so it was still fairly warm. It was along the time of the full moon in September. And how bright it was without the streetlights when the moon would shine. It was kind of eerie, in a way, kind of like during the War when we'd have the blackouts. Remember that? And I was a warden. It was my job to make sure that everybody had their blackout curtains drawn, no lights showing anywhere. You'd knock on the door and tell them that there was light shining from their window somewhere in their house. And they were supposed to take care of the situation. And the streets were--. Oh, they were so dark, well almost as bad as they are now, with the reduction in the number of streetlights that we have.

34:55

When I lived on Highland Street there was a streetlight on every pole. Now I guess there are about two on the street, to save electricity. Now we have a different reason.

MK: You were a young warden, barely twenty?

RC: That's right. I was about nineteen, in fact.

MK: Umm hmm.

RC: Yup.

MK: My dad was an air raid warden during the—

RC: He was?

MK: --during the War. Yeah. I remember about that.

RC: Yeah. Yup. Oh yeah, they took anyone that was still there. And when I turned twenty I had to register for the drafts. And then I went in the Service soon after, in fact about six months later I went into the Service. I'm losing my voice. So, yeah. And left Concord.

MK: Can we pause a second and--?

RC: Okay.

[pause to let Mr. Carter rest; interview resumes]

MK: In the event of a fire--. You were just--.

RC: Yup. In the event of a fire, the fire whistles at both ends of town--. One was at the Allen Chair Company in West Concord. And the one in Concord was at the Fire Station on Walden Street. We would get out our fire card, look up the number that was blown, and head for the fire. And sometimes you could, if you were an adult, of course, you could be of help. You could help remove furniture from the home. And, but most likely, the place would burn down! And it was really quite exciting to see, you know, a bathtub fall from the second floor, for example. And that's sort, that kind of activity. But we'd stay until it was practically one hundred percent out. And then we'd return. And in the meantime you'd meet your friends and neighbors. And it was a wonderful opportunity to get together! But it was part of our fun, our activities here in the town.

36:59

Other activities though were more joyous. We had an organization in West Concord called the West Concord Village Improvement Association. I guess it was shortened to just the Village Improvement Association. And at the Fourth of July, the night before, they would hold a activity on the playground of the school. And sometimes they'd have a minstrel show.

MK: Minstrel show?

37:29

RC: Yeah.

MK: Can you describe one of those?

RC: Yup. There would be various instruments. And there would be people who would recall funny things, jokes. And sometimes they would be about people in the town. And they would dance, and they would play instruments. Somebody would play the bones, you know, with the sticks in your hand, that kind of activity. I don't know just what you call it. And it would last for probably an hour. And then there'd be fireworks. And there'd be things to eat. There'd be soft drinks and hot dogs and that kind of thing. And that was the way we celebrated the Fourth of July. And--.

MK: Was the minstrel show in—

RC: Outdoors.

MK: --black, black-face?

RC: Yes, black-face. That's right. Yup. And of course the men who could sing were in demand to be, perform in these minstrel shows. And they were very funny. And we had another man, whose name was Tom Blood. He was a, worked at the prison. He was, worked under the overall title of Prison Officer. I don't know exactly what he did. But in the summer, on his vacation, he would join the, a theatrical group and tour the country, with his wife. She would whistle. And he would perform these monologues. He'd have costumes. He'd change his costume right on the stage. And he'd be all kinds of people, from a old country bumpkin to a, you know, a college professor. And he had stories to go along with each of his characters. And people would laugh. I never saw much humor, because I didn't understand what he was saying, particularly, because it was a little too, above my intelligence at the time. Anyway, he was funny. Just to look at him it would make you laugh. He had a kind of a--. He looked a little bit like a--. Oh, that fellow that used to be in the movies. Ahhh. Should've rehearsed this with myself before I began to speak, but--. Who was the--?

MK: Danny Kaye?

RC: No, older.

CK: Charlie Chaplin?

40:11

RC: No.

CK: Somewhere in-between, huh!

CK: Somewhere in-between, huh!

RC: Yeah. He looked a bit like you. He had long hair like you.

MK: . . .

RC: Winn. His last name was W-I-N-N.

MK: Don't know him.

RC: Well, you--. You must have known him.

MK: No.

RC: He was in your day.

MK: No, don't know him,

RC: Well anyway. He looked a lot like him and acted a lot like that actor. So. And he would perform in, at Concord at the West Concord Union Church. Often he'd be the entertainment at a church supper. That was an interesting thing. After the supper, they usually would have a sing-along. And the minister of the church, Mr. Stone, would sing. He'd usually sing, "On the Road to Mandalay." That was one of his favorites. And he'd get the audience to sing along. And they--. Mrs. Burly Pratt, Ruth Pratt, she would play the piano. And another lady, Carrie Derby, who had a beautiful voice, she would sing. She would lead us--. She'd sing "Carry Me Back to Old Virginny," Virginia, and all those wonderful old songs she would sing for us. And she would lead us in community singing too. And that was the entertainment, after the church supper. And we had a church supper about every month, from say January up through 'til Spring. And the--. The Catholic Church group, they put on a lot of minstrel shows. That was one thing that they did that was very entertaining. They'd perform at the Association Hall. And then there--. I understand the group in Concord was very active. They'd have, had their own hall, Monument Hall at Monument Square. And a lot of talent in that group in, musical talent.

MK: Umm hmm.

42:25

RC: Yeah. Let's see. What else should I tell you, about living in Concord? Oh, going to high school was an experience, I'll tell you, because we were told that there was going to be an initiation. They might remove your clothing. So you had to be very careful that you weren't caught and be dragged off into a corner somewhere and have your trousers removed. And we lived in fear and trembling as we came for the first day of school. Of course we came down by bus from West Concord, and went home by bus too. If you stayed for extra-curricular activities, you usually had to walk home. There were no buses that would pick up students if they were in the orchestra and rehearsed after school, or in the Dramatic Club or in Athletics. You had to find your own transportation. And mostly it was walking, two miles about. Some cases it was longer.

And meeting these very, as I mentioned before, interesting schoolteachers--. There was a girl, lady who taught French. Her name was Josephine Boynton. We called her Josie, Josie Boynton. And she would--. If you did not reply to her question, she'd call you, "Silly little person with your face hiding, like an ostrich, hiding your face in the sand." And that was her expression.

CK: In French?

44:06

RC: No, English! We wouldn't have understood her if she said it in French, I'm sorry to say! We had Miss Ware. She taught French. She had very good discipline. Even the biggest, strongest football players did not disobey in Miss Ware's class. She had excellent discipline.

And Gerty Dyer, she taught Science. An interesting thing about her class, she sat behind the table, where she'd perform her experiments. And if we would get out of hand, she'd let us get very boisterous. Then all of a sudden she'd take the yardstick, and she would slam it down on the granite top table. It was such a force that it would frighten the life out of us. And then she'd gain control again. And we would probably have to stay after school for having been a, so disappointing to her, being noisy.

45:30

Well, I did cover what you and I started to talk about. No, I didn't, did I? Oh. There was an organization in the country called the--. Gone from my mind. Wilfred Grenfell, Sir Wilfred Grenfell Association. Sir Wilfred Grenfell was an Englishman. And he was invited to come to Newfoundland to help the poor fisherman who lived in little coves all around the outs—perimeter of Newfoundland and in Labrador. And he established a hospital--He was a doctor.—in Newfoundland. And people began to collect money to send to him to operate his little nursing stations that he had established in the country. And one unit was established here in West Concord. And Miss Lucy Kay Snyder, I remember, was one of the leaders in the group. And they finally became involved here in Concord Center. They would meet at the First Parish Church once a month and collect money and send it to Sir Wilfred Grenfell.

CK: Grenfell? Spelled?

RC: Grenfell. G-R-E-N-F-E-L-L. Sir Wilfred. And it still exists today, a society called the New England Grenfell Association. And they meet in conjunction with a group form New York, and one from London, and one from Newfoundland. And they have these endowments that they have accumulated over the years. And once a year they approve or disapprove requests for grants form Newfoundland and Labrador. And a committee from members of each of these groups meets together and decides which ones they're going to grant and which ones they're not. And the--. They do that once a year. And it's quite a sizable sum. I would say it's close to a half million dollars every year.

MK: Hmm.

47:59

RC: And now that Newfoundland is now part of Canada, the government of Canada is doing much more and Labrador than they did before. So the need isn't as great as it used to be. But at one time they, the people were very poor, because they depended on fishing entirely. There was very few, very little industry in Newfoundland, just the fish industry, about all. So I'm a member. And I just came from a meeting. That's where I got my cold. They met at the Marriott Hotel down on the Waterfront in Boston. [sniffs] And we had a two-day meeting. We had reports from the four different groups. And then we listened while they read off the request for money. And we helped decide which ones we would grant and which ones we wouldn't. And that's, happens once a year.

MK: Still going on.

49:12

RC: Yeah. Still going on. Yup. And imagine a lot of the money came from here in Concord.

CK: Wow.

MK: I would love to get your recollections of your Service during the Second World War, but perhaps in the interest of time, we should ask you what it was like for you returning to Concord after your service.

RC: Well, one of the things that I recall was that it was like coming back to where everything had been inactive for a period of time. The Boston and Maine Railroad really, compared to what I saw in the rest of the United States, it looked like a Toonerville Trolley railroad to me. And you could almost see that the grass growing in the streets, because there had been such little activity while we were away. I don't imagine the town had money to do much in the way of, or the people to supply the labor to do the way of repairing the roads, and bridges, and the sidewalks, and so forth. So it looked kind of like, "Hey, this place needs to be, have a good reconditioning." And that started right away. We first got a new school in Concord Center and one in West Concord. And industry began to come to Concord. General Radio was one of the big industrial plants in West Concord after World War Two. And houses began to be built. The population increased, I figured out, about three and a half times of what it was when I was born here. There are around--. There are over 17,000 people here now, and there used to be only five. So--. Or six if you count the prisoners.

51:27

And new streets began to develop. And we didn't do much in the development of our commercial shopping area. It pretty much looks the same as it did back in 1922.

MK: Could we ask how your father's business fared during the War?

RC: Well.

MK: And after?

51:53

RC: My mo--. My father died in 1935.

MK: Oh.

RC: And my mother and her nephew ran the War up until--. It was about the time that I went into the Service, he also left and began--. He had a family, and he worked in a wartime factory after that. And my mother depended on itinerants, people who perhaps worked a couple of other jobs and had a little time to help her. And she pretty much ran the place by herself. And I had a opportunity to decide whether I was going to stay in the Military or come home and run the business. And I decided I'd give it a try. So I came back in '46 and ran it for another forty years. And finally closed it and had an out of, going out of business sale. And I sold the building to the Minute Man Association for Retarded Citizens and something else. And they occupy it now. So, no longer a store.

MK: Was there anything distinctive about the business, the line of furniture that you carried?

53:24

RC: We carried mostly 18th century reproductions. Yup. And a little contemporary. That Shaker-style that came to being did very well in that store. So we sort of satisfied a little modern. But we were pretty much traditional. There's this kind of appearance that you see in these two bookcases would be the type of thing we'd carry. And we had a very good business. We had--. I'd say we had the best of the select in the customers. And they were all very good, friendly people. And I served onboard an attack transport during the War. And there was one man from Concord onboard ship. His name was Dr. Peter Thatcher Brooks. And his aunt established the Brooks School here in Concord. And I still hear from him. And I hope to see him in Sept., in October this year when we have our last ship's reunion. And he didn't come to the last one because his family planned a birthday celebration for him at the time of our reunion. But it's one thing that I recall.

54:54

We made--.Went across in June of 1943. And we made the invasion of Sicily in Italy. Then we sailed up to Ireland. We took the 82nd Airborne to Belfast Ireland, where they, I understand, stayed until the invasion of Europe. But we came back to the United States. And then we went out to the Pacific. And we were involved in two invasions there, Saipan and Guam. And then I applied for entrance into the Navy Officer Training, the Navy V-12 Program. And so I left the ship at that point. And I ended up--.

MK: What was the—What was the ship?

RC: Pardon?

MK:What was the--? Which? What was the name of the ship?

55:47

RC: U.S.S. Frederick Funston.

MK: Frederick?

RC: Funston. F-U-N-S-T-O-N. He as a General in the Army. And we had a sister ship, the James O'Hara, and I think he was a General also. They had been Army transport command ships, but they turned them over to the Navy. And they were the beginning of their amphibious fleet. This is the invasion by ship.

MK: Umm hmm.

CK: . . .

MK: Yeah. So, after--. Can you talk about how West Concord began to change after the Second World War?

RC: Yeah. I think the thing that--. We had a separate post office in West Concord. And it was a first-class post office, due to the fact that--. One of the reasons was because of the industry in that end of town. One of the great users of the post office was the Bluine. They made a product that whitened clothes. Instead of the liquid blue rinse that you put the clothes through in, before the day of the automatic washing machine, this was a piece of paper. It looked like carbon paper. And you'd--. It came in a little booklet form. You tear off a little piece and put in your set tub with the cold water for the rinse. And it would dissolve and put a blue color in the water that would whiten the clothes. Because the soap they used was very yellowing as far as the washing was concerned. And I guess a mark of a good housewife was a real white wash flopping on the clothesline. So this was one of the things that would help you have a cl—nice white wash.

And they did a great business. People would sell their products, and they would get little rewards for having sold so many packets of this material. And children, young people, sold it. They would get rewards like a BB gun, or a sled or something like that. So the post office did a great business for this Bluine. So it became a first-class post office where the one in Concord Center was not.

58:27

Another thing was that the Reformatory generated their own electricity. So in the new Commonwealth Avenue that was built out to the Reformatory had streetlights, where there were no streetlights in Concord. There were just the lanterns, the oil lanterns. So anyway, the town always kind of remained a little bit distinct, especially socially. I was thinking back to the education. It--. Concord Academy, there were--. During my school years there were only two girls from West Concord who went to Concord Academy. One was Joan Pratt, and the other was Suzanne-. Not Suzanne--. Jane Servais. And they were the only two. And all the rest were from surrounding towns and Concord.

59:25

But now the private schools in Concord have a lot of children from West Concord, as well as Concord too. And the stigma of the separation of the two towns kind of disappeared after the War, then a great deal of the land that I--. Did I mention Dr. Pickard? He had the need of having a great deal of exercise, because he only had one kidney? He had had the other one removed, because it was diseased. So he bought a farm in Sudbury, adjacent to Concord. And part of it was in Concord too. And after he died, the family sold the property to a developer. And the developer wanted to be able to advertise that the property was in Con-cord, not West Con-cord. So he was able to get the postmaster to change the name of the post office in West Concord, from West Concord to Concord. So now you could live in West Concord and get your mail stamped "Concord" when you mailed it. So that kind of--. The stigma kind of started to disappear. I'd say it's almost completely disappeared now. And--.

CK: Was it a class distinction?

1:00:42

RC: Yes.

CK: Talk about that a little bit.

RC: Well, you know, in the early days, back to our Ralph Waldo Emerson, he was establishing sort of a intellectual, literary community here in Concord. He already had Henry David Thoreau living here. He invited Amos Bronson Alcott to come and live in Concord. And then he--. Alcott sold his house to Nathaniel Hawthorne, so there was another one. And then another lady by the name of Harriet Lothrop bought Mr. Hawthorne's house. And she was a writer. She wrote under the pen name of Margaret Sidney. And do you know what she wrote? Any of her books? She wrote The Five Little Peppers and How They Grew. Well, she was another author. And then he invited a man by the name of Franklin Benjamin Sanborn, who was by profession a journalist. And he invited him to come and teach school here in Concord. And he taught the children of Emerson and Hawthorne. Didn't teach the Alcott children. Mr. Alcott taught them himself.

1:02:00

But anyway, this community began to flourish as nice place to live, both as far as the land was concerned, and also because of the people who lived here. And then, the state government opened a District Court here in Concord, and as lawyers from Boston came here to try cases at the District Court, they saw what a beautiful community it was. So they began to buy land here and build houses. So it became a very, more intellectual, higher class--. They weren't farmers. Put it that way. They were educators and professional people. So that's how the distinction came about. But nowadays intellectuals live in West Concord as well as Concord!

MK: I haven't heard you mention the library in West Concord. Could you talk about that?

RC: Oh, yes. You know at first, the library was in the West Concord School, the wooden, Queen Anne-style wooden building that's no longer there, at the corner of Main and Church Streets. And when it became--. I guess when Mr. Loring N. Fowler, the man who owned the store on Commonwealth Avenue in West Concord, who sold it to my dad, he, when he died, he left his money for the library in West Concord. And so they built a separate building. And that was--. I don't know the year, but it was back in the early '20s when that was built. And they've had one addition. Now they're in the process of a second addition and a complete remodeling. It's going to be just as beautiful as this library, I think, when they finish. It will have accommodations for the young children, for older people, meeting rooms, and it's going to be a very nice-looking library. It was designed by a local architect, and I can't think of his name. He also did a remodeling of this building back in 1935. And his name was--. Oh, isn't that awful.

MK: Oh, now it'll come to you.

CK: It would be nice to hear a little bit more about Mr. Fowler.

1:04:40

RC: Oh, yeah. Well, I didn't know too much about him, except that he ran this store in West Concord, in which he, in addition to the furniture, he had musical reproduction machinery. He had phonographs. And they were the hand-operated phonographs. You wound them up. And then came the electric phonograph, and the radio. Well, people started, kids started, stopped taking piano lessons, for example. That was the business my father was in. He had a piano store in Maynard, the next town west of here. And he had, he was a musician by profession. He was an organist, church organist, and he was an accompanist. He had an orchestra. He was a school sup—music supervisor in the Maynard public schools. And of course after he married, he discovered that you couldn't make much music, much money in the music business. So he wanted to get into something a little more rewarding. So he bought Mr. Fowler's store. And he was--. That store was in a building. As you cross the railroad tracks in West Concord, it was the first store on the left. And next to it was Adamson Bridge's General Store. And up above it was a hall, Warner's Hall. In fact I guess Mr. Warner built that building. And then beyond that was the hotel that I spoke about.

1:06:29

And so my father's first store was there in that wooden building. Then he occupied Warner's Hall upstairs. And by this time the Bluine had gone out of business, and they were renting space in their multi-storied building. And my father had a floor in that building for his warehouse. Well, Mother and Dad were down at 51 Walden Street. It wasn't called 51 Walden Street. It was called the Veteran's Building, on Walden Street, watching a movie. And somebody came to my dad and said that--. Oh, they flashed on the screen, "Mr. Carter wanted at the box office." So he got up and went out to the box office, and he sauntered back to his chair. My mother said, "What's the matter." He said, "The store is on fire." So he, they left and came home. And evidently the fire was in Adamson Bridge's. And they had a paint shop there, and evidently somebody had been careless with an oily paint cloth, and it had combusted. And it didn't do much damage, except for smoke. Well, Dad decided right then and there that he was going to have a building of his own. And there wasn't much land available at that time in 1920, '20. This was two years before I was born. There was a store across the street that he could've bought, but the woman, the man's wife wouldn't sign off on her dower rights, so he could, the husband couldn't sell the property.

1:08:15

There was a lady on Main Street opposite this Harvey Wheeler School that had a tennis court. And her children had grown, and they weren't using the tennis court anymore. So my dad asked her if she'd like to sell it, and she said, "Yes," she would. So it was sandwiched between her house and Conant Machine and Steel Company. And so dad built a brick building there. And that's what happened. We were there until I went out of business, from 1929 until 1995 I guess.

MK: Wow. Did he maintain a friendship with Mr. Fowler after the initial purchase? Were they close?

1:09:08

RC: I don't--. Well he knew his brother quite well.

CK: Whose brother?

RC: Mr. Fowler's brother. I don't know his first name. But he had a funeral business in Maynard, and he had a son by the name of Guyer, who continued that business, and it's still in operation. It's still a funeral home up there in Maynard. It's in the different location—

MK: Umm hmm.

RC: But it's still in business. So he knew the family. And I remember Guy Fowl--. Mr. Loring N. Fowler had a daughter. Her name was--. Began with "O." And she was very fond of trees. And when she died she left a fund for the preservation of trees in Concord. Street trees. And Mr. Fowler was married twice. His second wife, I know was a Christian Scientist. And she drove one of those electric, early electric cars in which, as they drove along it looked like she was sitting in the back seat with a tiller in front of her. And she would drive up to the people that lived next to our store. What were their names? Anyway, they were interested in Christian Science. And she would come up to visit them. And I always thought that she was Mary Baker Eddy! She wore a big, tall hat, you know, probably late Victorian in appearance. And here she was seated in, appeared, looked like the back seat of this Coup, and! And I thought it was Mary Baker Eddy for sure!

MK: What an image.

[coughing]

1:11:09

CK: When you reflect now, how--? Other than the changes in the distinction between the two towns, what feels different about the social, the culture here?

RC: Um. How would I describe it? There's more culture. [coughing; recorder seems to have been turned off and then back on]

CK: Sorry?

RC: There are more cultural events here in Concord than there ever were before, although there were a lot when I was a child. There were literary events and musical events. There was a school here called the Concord Summer School of Music. And its director was a Thomas Whitney Surrett. And he held it at the Concord Academy. The Carter Furniture Company involvement was my father sold pianos as well as furniture. He would rent pianos to the Concord Summer School of Music. And several people were graduates. Did you ever hear of Catherine Davis, composer? She did, "Let all things now living rejoice in thanksgiving." That was one of her tunes. And the--. I was going to say, "The Trumpet Boy." That doesn't sound right. A Christmas tune that's very famous. I'm probably not correct on the title.

CK: "The Little Drummer Boy?"

1:13:00

RC: No.

CK: Anyway, you were talking about maybe changes in the social scene.

RC: Well, I'd say that it's more integrated, you know, more involvement of everybody in town, not just a few, not just a social class. Everyone is entitled to belong to these organizations. And I think there's a good representation from all parts of town. I think we have six precincts, which doesn't necessarily mean that there are six social areas of the town, but there are kind of distinct section of the town, the southern part over towards Nine Acre Corner in West Concord, the Monument Street area, and the center of the town. But I think there's more interplay between people that live in the town than there ever was before. And--. Yeah. I think we're, shall we say we're more democratic than we were?

CK: Including the people who have moved into those very large homes?

1:14:21

RC: They've become involved, slowly. Yeah. I knew so many people in town because I was in business. Probably somebody else would say that they only knew a percentage of the people, maybe not more than twenty-five percent. But I knew most everybody in Concord. Not everyone, but I knew quite a few people, and there were all walks of life. And so I feel a little bit more integrated with them than most people do, because I knew them. That's the whole thing about--. This whole business of class is integration; it's getting to know people. And if you get on a town committee, or something at school if you have kids in school, and, you really become more involved with everyone, and you don't have this feeling of any distinction. But if you stay secluded, and you don't become involved, I think you do feel that there are little cliques, cliques.

MK: Well that's a very optimistic rendering of the progress in the town.

1:15:47

RC: That's right. Yup. Now all these houses across the street were all individually owned when I was a child. And most of them were my customers later on. And as they died they, their property became available for sale, and the Academy brought them, bought them, purchased them. There was one woman that lived across the street there. She--. Her name was Mrs. Stuart B. Murphy. But she called herself Mrs. Stuart B. MurphEYQ! I don't know if anybody's still alive besides me who remembers her or not, but!

MK: From Irish to French pronunciation? Is that?

RC: Yeah. And she had kind of a trembly voice.

MK: Who were some of the great old characters that stand out in your mind when you were a child, as Thoreau would say, when you were "the boys?" "The boys were always there ahead of me," he said. Whether it was berry picking, or a fire, or whatever, the boys were always there ahead of me. Well who--? When you were running with, in the packs of boys, who were the great old characters that stand out in your head?

RC: Well, there was a boy named Harold Gibbs, who was a year older than me. He was quite a character. I remember he had an uncle who traveled to India. And when he returned, he brought Harold an Indian costume of a fellow that--. The cloth was wrapped around him and then pulled up between his legs, and tucked underneath the last roll at the top. And then he had a turban. Well, the schoolteacher of our class decided that Harold should be able to demonstrate this to all the classes in the grammar school. So he chose me to be his pupil. And as he would put that cloth around my body, and then he's bring it up through, between my legs and up until the last roll of cloth up here by your stomach, he's give it an extra pull, and I practically could tip right over in the classroom. Of course that was the delight of the kids. They loved that. But he was a performer. Everything he did he did to get attention. And I guess there's a psychological reason for why he did it. But he was--. He had a--. Probably he was five or six years old when all of a sudden there appeared another brother. And the brother received all the attention. And then of course he felt he had to make up for it. And he performed. And—

MK: But the old, the old characters around town that you might--.

1:18:41

RC: Well, there was a gate keeper that lived on my street, Charlie Carole. And he spent his retirement in Charlie Lombardo's Barber Shop, smoking his pipe. He'd sit there all day long. And he and Charlie would exchange stories about various other characters in town. It was quite interesting. One man I know used to say it was worth the price of the haircut to hear Charlie's stories.

MK: Uh huh.

RC: And the--. There was a lady who was a character. She was a horse woman. I understand she was the only female member of the Musketaquid Sportsmen Club in Concord. And she did business with me. We used to re--. You probably never heard of repairing, remaking hair mattresses, did you? Well you know hair mattresses were the mattress to have in your home years ago. And if they were made out of white horse hair, instead of the black, they were considered very top quality. Well, they would flatten down after a while, and they would retain the impression of your body, and they needed to be re-garnetted, so to speak, reworked and put back into the ticking, and re-tufted again. And we would do that. We'd send it to a factory in Boston that would do it for us. And evidently one of the institutes that helped the blind people also did this sort of work too. It was something they could do if they were blind, or poor sight. Anyway, this lady said to me, "My cousin, Mrs. Charles Francis Adams, had her mattresses remade at much less money than you charged me." And of course she was very wealthy herself and could afford it. I just had to say, "I'm sorry, Ma'am, but that's what we charge." She did pay the bill.

MK: But she was quite an equestrian, was she?

1:20:54

RC: She was. Mary Ogden Abbott. She's gone. Her house that she lived in is still on Sudbury Road. And it was the site of the barn in which Daniel Chester French sculpted the Concord Minute Man. That was on her property. And that was later removed and became part of the Concord Museum.

MK: The barn was?

RC: Yup.

MK: Wow.

RC: Taken down board by board, and reassembled at the Museum. I don't know if it's exact replica, but it's made out of the same materials anyway.

CK: You must have really had to have such a refined style of behavior dealing with all these customers.

1:21:47

RC: We had another lady. I won't mention her name. She came from New York originally. And evidently she had had store teeth made, false teeth, dentures. And they didn't fit just properly. And when she talked they rattled, you know, back and forth. I don't think she realized it either. But she was a character. She always used to come to the store and say, "In your back room don't you have something that's damaged that I could buy cheaply?" And she lived in a very nice neighborhood!

MK: [Chuckles]

CK: And your answer?

RC: "No, I'm sorry. We don't have anything. We don't have a back room!"

MK: [laughs]

CK: [laughs]

MK: Oh, this has been wonderful. We thank you. Thank you, thank you--

RC: You're welcome.

MK: --very much for your recollections.

RC:I hope it doesn't cause somebody to sue me or something!

MK: [laughs] I don't think it will!

RC: Okay.

MK: You've been very discreet.

RC: Good. I hopefully. I don't think Mary Odgen Abbott every married, so I don't think there are any heirs in the--.

MK: No. It doesn't seem likely.

RC: No.

MK: [laughs] . . .

RC: Well, this has been fun.

CK: Thank you.

1:23:10

END OF INTERVIEW