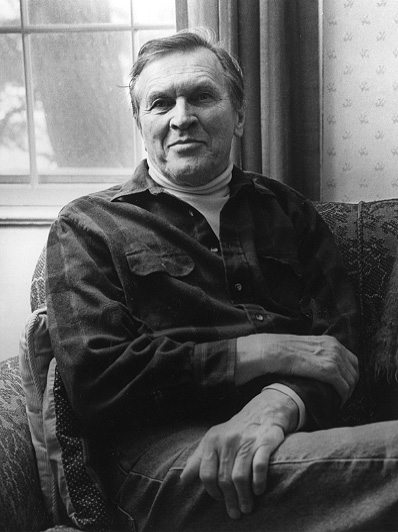

Dr. Donnell Boardman, Internist

Acton Common

Age 75

Interviewed November 9, 1988

Concord Oral History Program

Renee Garrelick, Interviewer.

Perspective on Primary Care Medicine.

Click here for audio in .mp3 format.

-- Efforts to begin prepaid group practice

-- Efforts to begin prepaid group practice -- House calls

-- Impact of technology on patient-doctor relationship; medical malpractice

-- Formation of the Acton Medical Associates

-- Introduction of Boston University School of Medicine preceptorship at Emerson Hospital

-- Emerson Hospital staff

-- Pacifism, medical service during World War II in Japanese Relocation Camps. Atomic bomb explosion

-- Quaker Mission Hospital in Kenya

-- Physicians for Social Responsibility

-- Study of human effects of ionizing radiation

-- Teenage drug problem, late 1960s

At the end of World War II, my wife and I had thought to move

into the Boston area rather than the New York area where we had

both grown up because academically it was more favorable and

because you could live in the country and still be close enough to

the metropolitan center and the academic center. We came with

four small children. I came first with two run-about children,

and we slept our first night here in the old homestead across from

the library. When there was no fire in October, we slept on the

floor in the dining room of a house that I bought before the

family ever saw it. The two children and I had breakfast at

Howard Johnson's, a new restaurant in Concord. It had just

started up at that time. Mother and months-old twins arrived

later the next day.

We came to Acton because it was in the country but within

striking distance of Boston's medical, academic, and cultural

centers. There were only 3200 people in Acton at that time. It

was a nice country village with apple orchards, dairy farmers, and

truck farmers. A few people worked in Boston, but not very many.

It was our intent to become a small group practicing medicine

hopefully with a patient-consumer cooperative prepaid medical

plan. As time developed it turned out that it was a group of two

offices, one in Maynard and one in Littleton, and two hospitals --

Emerson Hospital in Concord and the other what was known as the

Mass. Memorial Hospital in Boston, part of Boston University. I

was running between two offices and two hospitals. About four

years later Dr. Henry Stimpson Harvey joined me because he was

also looking for a country practice near a metropolitan center,

and we had other similar interests.

The United Cooperative Society was a consumer cooperative of

groceries, hardware, coal, and oil started by the Finns who lived

in Maynard while they worked at the American Woolen Company. That

cooperative started really because the mill workers found that

most of their paycheck provided by the American Woolen Company

went back to the American Woolen Company because they had to get

all things at the company store and other places that took

advantage of their sort-of isolation. They got together to

develop the cooperative endeavor so that they could control the

prices that they had to pay for food and the common household

needs. Indeed, they found it made an enormous difference, and the

Cooperative Society was extremely successful for at least 10 or 20

years after we came in the 1940's. It really died when most of

the younger generation of Finns who had any get-up-and-go got up

and left. That left the older people, the diminishing number of

Finns and the diminishing number of mill workers as a central

core. A lot of people who moved into the area, which included all

the towns around Maynard, had an intellectual and ideological

interest in cooperatives, but they didn't have the tight-knit

cohesiveness provided by the American Woolen Company and by the

Finns. So it gradually became less and less loyally supported.

At the same time the Stop & Shop, the supermarkets, began to move

in, and I think the first one was the A & P and its prices in

Maynard were substantially lower than they were in Concord because

they were trying to out-compete the cooperative. Well, with one

thing or another, competition did prove to be too much for the

Cooperative Society, and it succumbed. One of the reasons we came

was not only the Cooperative Society but at that time we were

looking into seriously and hard at getting pre-paid medical care,

but their whole idea of medical economics was very different than

even mine as an emerging idealistic dreamer. With four small

children, even in 1946, I thought that $8000 a year was pretty

meager for a well-trained physician; but the salary of the general

manager of the cooperative, which I think by that time was a

million dollar a year proposition, was only $5000. They couldn't

see paying a young man anything like that figure, so we never came

to any kind of an agreement, and the prepayment never materialized

until some 30 years later.

There were about five doctors in Maynard when I arrived and

most of them with one exception were significantly older than I.

Only one of them had any access to Emerson Hospital, and he did

not make use of it, so that the medical care provided in Maynard

particularly was, should we say, limited. For serious illnesses

patients found that they went even beyond Emerson Hospital. They

went into Boston because the local physicians, if they referred

them to Emerson Hospital, were likely to lose their patients to

Emerson Hospital based physicians. Even at that time though

Concord and other towns used Boston at least as much as they used

Emerson Hospital. Emerson Hospital itself had an ambiguous

reputation with the population. There were some who felt that the

patients went there only to die or to prepare to die. I don't

think that was fair, but it was understandable because since it

was limited, people usually got there too late. It seemed to me

it was very obvious that Emerson Hospital had tremendous

potential. Charlie Duston was a very competent technician and a

very competent businessman, and really did a lot to improve the

image of Emerson Hospital.

When I first started, my office was on Nason Street in

Maynard over the A & P. We came to the area, as I said, because

of the possibility of cooperative prepaid medicine. My interest

had led me up to the Boston area because I had some medical school

training in Boston under Paul Dudley White, the cardiologist, and

a number of others; but I had also known several other MGH doctors

who had been interested in the White Cross, which was the first

prepaid group practice started just before World War II. Dr.

Edward Young thought that the White Cross itself was a war

casualty, that all the doctors who were participating were

eligible for the service; and they got pulled out, and there was

no one to provide the service. Therefore, it fell apart. Interestingly enough, he, Alan Butler, Hugh Cabot and several others

were called up before the medical society in the early 1940's and

were asked why they shouldn't be thrown out of the medical society

because they were practicing a socialized, almost communist

concept of medical practice. They weathered that, but the drain

on the doctor participants yielded to World War II. They were

quite interested in my coming into the area with this interest,

and so they were very nice. Robert DeNormandie was an obstetrician who lived in Lincoln and was probably the dean of clinical

obstetrics in the greater Boston area at that time. He did a lot

to help introduce me and my credentials to a blue-stocking

population in Concord and Lincoln, so that I garnered a number of

families of the cultured, educated, and sophisticated population

of those towns. At the same time, it was well known among Finnish

mill workers that I was coming equally well-approved, so that I

got started fairly promptly. My wife and I celebrated when I had

a day that grossed $30 -- that was a big event!

Night calls, it always seemed to me, were extremely

profitable to physicians. I sort of deplore the loss of house

calls in the present day because it seems that doctors really

never get to know their patients if they never go into their

homes. In a period of high tech and computerized billing, this

separates the doctor from the real essence of medical practice.

What we were saying about how sick we are between the ears is ever

so manifest. I remember getting called to see a man who had a

fever just outside the center of town. He was desperately sick,

103.6 degree temperature and his whole body flaming red and

beginning to pustulate. He was a man in his late twenties with

chicken pox. He survived, but I learned not only about that but

about his children and about his wife, who turned out to be at

that time in and out of a sort-of schizophrenic behavior. I

learned about how that family lived. It was extraordinary. You

go and see people in their homes and they are very different than

they are in the office. Night calls were particularly revealing

in that way.

I think that medicine has lost a lot because doctors have

gotten caught up so much, necessarily perhaps, with high

technology which has been developed by the electronics industries,

but to the detriment of their relationship with people and the

people's family constellation -- all of which contributes to the

illness. Yes, I think house calls and night calls were

fascinating. It got a little irksome when you got called by the

police to make a house call and then as happened to be on one

occasion in response to the police having called me, I was

hurrying to the house and had one of the town police cars stop me

for speeding. That was really annoying, but usually it was a very

interesting thing.

There is a very famous caricature cartoon that shows the

patient lying in bed with his head swathed in bandages, the doctor

standing by the bedside, his doctor's bag opened, the stethoscope

drooping out, and the doctor holding a pen and wetting it to his

lips as he writes on the white wall behind the patient his bill

for his services. He has got a whole lot of things itemized. The

point being that the doctor makes his living at the cost of the

patient's discomfort. On the other hand, there is no question

that an eye-to-eye and face-to-face confrontation of patient and

doctor has a disciplinary effect on the doctor's charges and his

compassion. If he really finds that what he is asking for hurts

the patient because he sees it on his face, then he is able to

modify it. The introduction of third-party payments has removed

all that. Most people, including the doctors, don't have any idea

what the costs are that are being generated in a doctor-patient

relationship in the HMO-type of practice.

On the other hand, the fact that big business has moved in

and complicated medical care, there is an enormous overhead you

have to pay for the business administrators. The high-tech, as I

have indicated before, has gotten to be so expensive. If you have

an expensive diagnostic test machine in your office, you have to

use that machine to pay for that machine, and you have to charge

the patient for it. You use it -- sometimes it helps and

sometimes it confirms. Usually it does no more than to confirm

the doctor's decision on whether the patient does or indeed does

not have what the test is supposed to show. It all separates the

doctor from the patient. To my mind, that is the essence of

medical care and indeed in human relations -- one-to-one sharing

of the responsibility of the patient's malady. If the doctor

doesn't encourage the patient to meet his misfortune and meet his

disease with him, then he is going to have less success and

perhaps be another failure. It seems to me if you would list the

patient's help in his cure, then you have pretty well insured that

patient as a colleague and as a friend and not an adversary that

you are going to meet in court over a medical legal practice.

I have always felt that generally speaking a patient that

develops medical malpractice has got a basis. It usually is a misadventure in the medical management, irrespective of the fact

that the patient also may or may not have had a fatal or a

crippling disease; but usually there is a mistake of one sort of

another. The reason it gets to court is because there has also

been an alienation between doctor and patient. This is particularly true in a complex system whereby the disease is treated by a

team of doctors, none of whom address themselves to the care of

the patient. They are only treating the disease, and the patient

and the family very often feel left out and then they begin to

have doubts. Then they begin to ask questions, and there is

always somebody to go to and they'll say, "Yes, you have gotten a

rough deal." That is what seems to me a major disaster. This is

after all the common phenomenon in our socio-economic society

anyhow. There is very little trust now. You have to have a

credit card. The idea of going in and saying, "I am me, I've been

around and you've been around for 20 years, we know each other, we

trust each other," is a thing of the past. There is just no more

of a warm vibrant community, unity, and confidence, and it is very

sad because it lends to the climate of distrust in every aspect of

our human relations.

As you know the Acton Medical Associates now has 14 or 15

doctors. While I was there we never got bigger than six or seven.

Acton Medical Associates began in 1957 but it was really formed

when Ed Bell joined us in 1954. Henry Harvey came in 1952. Two

was a partnership and three qualified for a group or an

association. We paid $3,000 for the land, it was too much for

that piece of property, but I think it is fair to say that it is

probably valued at 50 to 100 times what we paid for it now. The

building has been expanded, I should say doubled and then

quadrupled in size, so I guess it was a pretty frugal and

worthwhile business venture.

We felt that group practice was very important. There

should be a free interplay between covering for one another. As

the group developed the group was interested, even as I had been

interested, in having a personal one-to-one relationship, so we

always asked patients to choose one of the doctors to be their

personal physician, or for the family there would be a family physician. If they, over a period of time, wanted to change that,

they should feel perfectly free to do so, but there should be a

one-to-one relationship. That survived pretty well even when

there were five and six members of the group. We all had our own

loyal following, all of whom were perfectly willing to accept one

of the others as a replacement for on-call, vacations, holidays,

or things of that sort. There was always a one-to-one relationship, and that as I said survived as long as I was there.

I joined the staff at Boston University and in 1948 and did

some outpatient teaching three times a week throughout the school

year. Then some six or seven years later, since I was a great

advocate of country practice and the practicing physician in a

semi-rural area having at least a toe-hold in an academic

situation, I wanted to promulgate that. So I went and talked to

Dean Jim Faulker at B.U. School of Medicine, and he was very

helpful encouraging me to start what was called a "preceptorship,"

which got fourth-year medical students to use one of their elected

periods to come out and work with me as preceptor to learn about

the clinical practice of medicine in a community that included

industrial medicine, school physician, sports medicine, as well as

clinical practice in office, house calls, and hospital. The first

year I tried to introduce this at the Emerson Hospital there was

one member of the staff who was outraged at the damn thing and

then talked to all the doctors about the ill-advisability of doing

this and suggested that I was just using medical students to spy

out my colleagues so I could get the advantage of them. When it

came to a vote, the vote turned out to be, I think, thirteen to

one. Within weeks the doctors in Boston and in the teaching

hospitals all around who had any contact with the Emerson Hospital

staff members were asking questions -- "What happened to Emerson

Hospital? Why did you lose such a wonderful opportunity?" The

next year it got started, and it went for a good 10 years from

1953-1963 as long as I was at B.U., and we really had a

fascinating time. Students were very enthusiastic. They proved to

be good learners, and they kept not only the members of the Acton

Medical Associates, which was growing at the same time, but also

members of the staff at Emerson Hospital on their toes. Witness to the fact that even though that preceptorship came to an end, it

has since been re-established by younger members of the Emerson

Hospital staff so that I felt it was a good thing well worth

starting. It was lots of fun -- just lots of fun.

I served on the Emerson staff essentially from 1946 to 1986.

I went away for a couple of years in 1978 to 1980 and then came

back and practiced more or less on my own but under the roof of

and with all the office and nursing support of the Acton Medical

Associates, but I did not rejoin the Associates. So I was there

for 40 years.

I had a very clear idea, at least I thought it was a very

clear idea, of what practice could be when I came to Emerson. I

came to Emerson because it was in the country and close enough to

be associated with teaching and academic medicine in the city. I

came, as I look back at it, with a good deal of self-assurance and

confidence in the idea and I made it very clear -- there wasn't

any question in my mind. Older men who had been themselves

well-trained, many of them at Harvard, took some exception to my

being outspoken and my being ambitious in this way. Yes, I was

quite outspoken. The laboratory at Emerson consisted of a

part-time technician who stopped on his way back home from another

hospital laboratory and did the laboratory work for the hospital

between 5:00 and 6:30 in the evening. My immediate reaction was,

"That's not enough!" I said so. Well, I made a number of other

comments which may have touched closer to home. At the end of the

year the chairman of the board of trustees caught me in the car at

the hospital and asked me whether I thought there was any reason

why the board of trustees should reappoint me to the staff. I

just stopped in the car and said, "Can you give me a reason why

they shouldn't?" He didn't answer, and I don't know what he was

looking for when he asked the question. The question or the

appointment never came up again.

It is interesting, you know, I never did raise questions that

were totally unacceptable or unthinkable by my colleagues.

Usually when I raised an issue, there sort of was a startled,

electric silence after I asked the question but people would come

up to me after the meeting broke up and as we walked down the corridor said, "Don, I am so glad you brought that up ..." I

said, "Where were you? I didn't hear you speak up and defend ...

"Well, you know ......" And this happened over and over again,

but it was a good relationship. Once the Acton Medical Associates

got established, just the fact that they were there, my partners

really didn't have to speak up because it was known that they were

my partners, you see. I almost never asked any questions at staff

meetings without having sort of fielded a sense on this subject

with my partners and with one or two other people. The staff

really did get to be a lot more liberal and a lot more open as

years went by. Within the next ten years, not only Acton Medical

Associates but lots of new doctors came who were much more

receptive to new ideas. Witness to the fact that Emerson is now a

very impressive, almost top-flight care at a time when hospitals

are having a rough time.

I have gotten in and out of jail I might say on social

issues. Yes, I spent a night in jail in Washington, D.C. I was

sitting on the sidewalk in front of Mr. Nixon holding him in the

light as the Quakers say. That just so happened to have been the

weekend before Washington D.C. law and order was expecting the big

demonstration in Washington which took place, and so I have always

felt that when they picked up something like 100 Quakers that

Sunday they did so to serve as a warning to those who were going

to come the next week.

If World War II had come much earlier, I wouldn't have been

as well prepared to provide service to my fellow man because I

wouldn't have completed my formal medical training. If it had

come a little bit later, I wouldn't have had the same opportunity

to take a position. Most particularly, the fact that I had had my

post-graduate training in medicine, so that I was fully prepared

to take on a job that the government could use. They could see

that they were going to need doctors, whether it was in the

military or out of the military. So they made good use of the

fact that I was a qualified doctor. When I found out that the

American Friends Service Committee were helping conscientious

objectors, I got in touch with them and they said, "Go and ask the

Civil Service Commission about the Japanese Relocation Camps." They were delighted. Most of the doctors they had were really

marginal at best. I said I am a young man and I recognize the

word in an emergency and I am ready to go anywhere, do anything

and be moved around, and my wife is quite understanding and is

willing to cooperate." We went to be troubleshooters for the War

Relocation Authority, which was designed under the Department of

the Interior, under Harold Ickes who was just a delightful person

to work under. He had a vision -- you could feel it even in the

ranks way down where we were in the mud of Arkansas, in the desert

of Arizona, to provide the necessaries of medical care to the

Japanese Americans and the Japanese who had no citizenship that

were moved out to the West Coast war zones and were put into these

camps.

The physical insult and hurt was far less than the

psychological, the economic, and the social isolation -- focusing

on them just because they were of Japanese heritage. It was

devistating to a self-respecting people who had really made their

mark and contributed enormously to the wealth of California

particularly as farmers. They were just very good industrious

people. Well, in the end it turned out there were ten camps, and

I served in seven or eight of them. There was one time I thought

I knew more Japanese-Americans on first-name basis than most of

the Japanese-Americans in the country and wherever I went it was

to go to a place of greater urgency and greater need than where I

already was, so it was a great experience. I always felt it was

by far the most creative way to spend war years for young men that

could be done. By and large almost every young man who lives in

the country through an era of war is a war victim. They are

scarred for life by the experience they had closely associated

with the war, whether they served in the military or not. The

compromises, the attitudes of mind are so disforming and so

warping from a creative, positive way of life, that it is

devastating. I felt by far that this was the least injurious way.

As I said, I always felt that I was particularly favored.

I went off to the first assignment leaving Elizabeth and the

new baby, a year-old baby behind, and she joined me about three or

four months later. We were discussing this the other day with this chap and his boy visiting us today, we were talking about how

many of the camps she had been to. And it turned out that she

also had been in six. She did one stretch of teaching in the high

school, teaching English to the students, one of whom later was a

medical school student, and having been taught in high school by

my wife was taught in medical school by me. Several others, one

who was president of the class told me that he thought that

evacuation of the Japanese was one of the best opportunities of

his life. It had gotten him away from just the parochial scene in

California and he was headed off to an eastern college.

There were those who felt that this was quite a positive

experience; but there were a lot of people, particularly the older

people, who were much hurt by it, and their self confidence was

really shattered. So it was a disaster. But I'm delighted that

even 40 years later it has been acknowledged ultimately and

ostensibly supposed to be given some kind of compensation.

I was there when the atomic bomb was dropped. We were in

Tule Lake, which is the largest and the last of the camps. There

were 18,000 in Tule Lake, and we were there for something over a

year at the end of the three and a half years. My wife was

pregnant with twins and had two runabout children and we got Mrs.

Sakari a Japanese born woman who knew very little English but just

enough to make do with Elizabeth's help to communicate with one

another.

August 5 came, and a train came down the track toward the

camp down the valley blowing it's whistle until the steam ran out

and the whistle just drooped out and died; and the news came

almost instantaneously from up in the camps that Hiroshima had

been bombed. Elizabeth turned to Mrs. Sakari and said "Mrs.

Sakari, don't you come from Hiroshima?" And she said, "Yes, I do."

Elizabeth said, "You have family?" She said, "Two sons, my

parents and all my brothers and sisters." Elizabeth said "Oh,

dear, perhaps you should go home and be with your husband and

family." She said, "No, I take care of the children." By this

time the twins had been born, so she got all four of the children

taken care of and then she said, "Perhaps I go home." It took

time for everybody to begin to understand the full implications of

this, and it was a sorry time.

Mrs. Sakari was released because the war was over and went

back to Sacramento, and a good friend of hers who stayed in camp

working with another family came and checked in on Mrs. Boardman

and her four babies. She looked around and said, "You can't do

this, you need Mrs. Sakari, I send my daughter." So Mrs. Sakari

came back and much to the surprise of the military police who sent

word, "There's a Jap out here who says she just got out of the

camp and now she wants to come back in, is that all right?" So my

wife went out and said it was all right that she was coming to

help her. So that was our first intimate association and our

first concern with radiation and the nuclear bomb and all that

sort of thing.

To my knowledge her family lived in the center of Hiroshima,

and we never heard a word. Very little was known about the true

dimensions of that thing for five years. Nothing came out of the

military. We never knew their fate. We assumed, of course, that

Mrs. Sakari lost all her family and her two sons, but we never

knew.

We didn't become Quakers until after the Korean War because I

didn't want any question for the Selective Service Board about

joining a peace church to avoid the draft. It was a special

doctors' draft, the Korean War. I got called up and submitted a

conscientious objector plea in which I sent a copy of what I had

written ten years earlier and said nothing has happened in the

intermittent ten years to do more than confirm my opinion. They

wrote back and classified me as too old to fight. After that we

joined the Friends, and through the Friends we learned about the

Quaker Mission Hospital in Kenya. I don't really know why it

seemed like such a good idea to both me and my wife to go. They

had a doctor that was finishing up and two other doctors that were

going three months later, and I said it was obvious they needed

some kind of liaison, so I volunteered, having had a splendid

time. I enjoyed it so much that I kept talking about it, so that

when I got to be 65, my wife thought it would be a good way for me

to get out from under the Acton Medical Associates. Given my

temperament, she thought that it was unlikely that I could truly

retire from the Acton participation staying there, and I agreed,

so we went off for two years.

When we came back from Africa, the Physicians for Social

Responsibility was being reactivated by Helen Caldicott, the

Australian pediatrician at the Children's Hospital, who had been

concerned with the uranium miners in Australia. She and her

husband both came to teaching positions, but she became very much

concerned with nuclear energy, as indeed a lot of people were.

The atomic veterans had just come to recognize themselves after a

25 year silence. They were just beginning to be aware of the fact

that they had been exposed and that many of them who had no

connection with one another, because there was very little buddy

activity generated or encouraged among atomic veterans, began to

recognize that they were a marked group. It became increasingly

apparent that these men had more exposure than was officially

acknowledged and that they were sicker than they should be. Their

sicknesses didn't fit any category that the Veterans

Administration was going to recognize as convincible as service

connected. Then it became increasingly apparent that these men

didn't really have the kind of disorders, at least some of them,

that other people had. Again, here is where time makes a lot of

difference. Had I been a young physician, I wouldn't have been

secure about being able to tell the difference between malingering

or psychoneurotic or opportunistic complaints. After 40 years in

a mill town, you really do begin to know how to tell what is real

disease, what is imagined disease and what is feigned disease. It

was very clear as you reviewed, and I reviewed close to a couple

of hundred by now, medical records, that many of these men had an

exposure to ionizing radiation of sufficient and significant

degree so that they were sure that they had been exposed but not

enough for them to have had a recognized and officially

acknowledged diagnosis of acute radiation sickness. Many times

they would go to see the doctor at the VA or on duty in the

military service or subsequently in civilian life and the doctor

would say, "You had radiation sickness." But then when push came

to shove, it turned out that the records said that the guy had had

too much sunburn and too much beer, and that is why he got skin

rash, nausea and vomiting, and bloody diarrhea. So the official

records more often than not never had it.

Over and over again you would find that the guy who knew all

his buddies and had pictures of where he had been at the Nevada

test sites would write in and there would be no record of his ever

having been there until he pushed and pushed and finally got his

lawyer to write a freedom-of-information act letter. Then they'd

say, "Oh yes, he was there." After awhile they'd say, "Our

records got burned up in St. Louis," or "Our records got lost,

mislaid or incomplete, so we will accept any veteran's assertion

that he was there on face value if we don't find the records to

the contrary." Then it became apparent that these guys were sick

and they couldn't really identify what their major difficulty was

except that they had never felt quite up to what they should be.

There were lots of malingerers, constitutionally inadequate people

who were never able to face life. This was different. These guys

had specific complaints, and later you could find objective

physical findings that didn't fit other categories of disease.

This has become so apparent in so many of the records. I think

that probably 10% of the hundreds of cases that I have reviewed

closely, and have reviewed in general with other people who are

concerned with this problem, had this syndrome. It is almost

surely got to do with the nature of ionized radiation which does

not hit this organ or that organ or this part of the body or that

part of the body, but will go through the body and hit at random

any molecule in any chemical constituent or any part of the cell.

The cell is a great big thing, as big as the human being when you

can start thinking in terms of molecules. There are billions of

molecules in just the chromosome. The chromosome is only a small

part of the nucleus, and the nucleus is only a small part of the

cell, and the cell is made up of all sorts of complex things, each

of which is made up of molecules, which have got hundreds of

thousands of atoms in them, and each of the atoms has a number of

circulating electrons. Ionizing radiation pings off these

electrons in these atoms, in these molecules, in these fragments

of cell, and the guy just doesn't feel right. It may kill the

cell and then it gets replaced with fibrous tissue or it may

change the protein that makes other proteins, that makes other

enzymes, and they are all a little bit off, so you couldn't know what was going to happen. If you'd look, you would find that this

does actually happen at very, very, very low levels of ionizing

radiation. Most of the x-rays that we have taken, chest x-rays,

diagnostic x-rays, are measured in thousands of electron volts;

and if you take a series of them, you just multiply them. You can

disrupt things with very small amounts. Then it gets more and more

complicated, but this has been the problem as I have seen it. I

came at it, being a clinician, from a clinical aspect.

I came at it from hearing men tell their stories about what

has happened to them. To put their stories together in a

cause-and-effect relationship to something that happened to them

35 years ago is impossible, and that is what has been known as the

doctors dilemma. But if you see these stories and you see these

patterns of disorder happening over and over again, and you

recognize the molecular and physical and chemical basis, that that

is the way radiation works, then it not only justifies it but it

explains why it is the way it is. That is where we are at the

present time. This has all been complicated by the fact that

since the day after Hiroshima, everything to do with the human

hazards of ionizing radiation has been relegated to the Department

of Energy. It was originally the Atomic Energy Commission in the

military, but now under the Department of Energy, and 27 national

radiation laboratories and what is known as the Oak Ridge

Associated Universities, Oak Ridge, Tennessee, one of the major

radiation facilities government run. The 80 Oak Ridge Associated

Universities are the key universities throughout the country that

have big nuclear physics facilities, and they are all very well

dominated by men who understand what shall and what shall not be

disseminated for general consumption. You go to the government

documents catalogue and everything you get out of there is

stamped, "Cleared, Unlimited Distribution," which means that there

are other things that are not cleared. So that I have persuaded,

having spent a lot of time studying how radiation works

particularly in human tissues, I have persuaded there are a number

of very good scientists and health physicists and physicians who

are equally assured that this is indeed a fact and that we have

absolutely no idea of the degree to which damage is being done. I am not saying it is absolutely destructive. I am just saying the

evidence is that it is far more destructive than the general

public has been allowed to believe. So that is what I am doing

right now.

Almost 20 years ago the high school kids saw their

out-of-high school colleagues meet right here across the street on

the common in front of the town hall. One night one of the young

people that I knew very well shouted, "Dr. Boardman," right from

the monument out here, and called because one of his buddies was

over there with an overdose, I guess it must have been heroin

because he had a respiratory arrest. They got the EMT, and the

EMT gave him artificial resuscitation and took him off to the

hospital; but it was as blatant as that -- the teenagers

collecting night after night out here in front of the town and

exchanging and smoking a lot of pot, etc. Two of the younger

doctors of the Acton Medical Associates, Jim Longcope, who is now

a psychiatrist on staff of Emerson, and Bob Shumacher, who is a

pediatrician who went out to the Indian service for awhile and

then came back to a private pediatric practice in New Hampshire,

got together with some of these young people, who we knew as

patients and as contemporaries of some of my children, and we had

about 25 enlisted people who came every Tuesday evening to talk

about the drug problem. I've always thought it would be a good

idea for us to do a follow-up. Well, with 25 that we knew of, the

general agreement was that there were at least 50 mainline

shooters, intravenous heroin users, in our community. That

included Concord, and I don't know how far beyond Concord, Acton

and Maynard. We figured at that time that 50 hard-drug users in a

community of a few thousand represented a higher incidence of

heroin addicts in our community than was reported in New York

City. That made us sit up and take notice, and so we started

talking about it, and talked to these guys, and talked about how

useless it was and what a dead-end track it was on. We never

felt, the three doctors, that we really had much impact other than

we represented the established community who was willing to talk,

listen, and appreciate them as individual human beings. Who's to

say whether that had any effect? All I can say is at least one of them got on the methadone and became a lawyer, another one has

been in and out of rehabilitation for the next ten or twenty

years, one turns up every now and then and reports to me on some

of the others, and to my knowledge none of them are dead yet. Of

course, here it is '89 -- it is almost another 10 years, it is

almost 20 years. One of them really kicked the habit entirely and

became a laboratory supervisor in one of the teaching hospitals in

Boston, and his sister also was able to kick the habit. So some

of them got off it, some of them are still struggling with it,

some of them are lost to it. When I came back from Africa, it was

ten years from this Tuesday evening group, I asked around if the

drugs were any less. Those who were in the know said, "On the

contrary, it is probably much worse, it is much more undercover,

and it is a much younger group." I never undertook to get

involved with it again. Perhaps I should. I thought perhaps

somebody else should becoming involved again.

I guess I would say the older I get, the later it gets into

the century, the longer I watch the common scene, the more

impressed I am with the general lack of interpersonal

communication and interhuman compassionate awareness we have for

one another, not only in medicine, not only in nuclear energy, not

only in the high-tech modern medical management, but in every

aspect of human endeavor. I think we are in very precarious

times. I don't believe that I am alone. Bill Moyer has been

having people provide a world of ideas near midnight for the last

month. Everything that those people said sounded very familiar to

me and really very ominous. Of course, we all end up on a note of

hope. It has got to be better. It is too good to be over with.

It seems to me that Albert Einstein was speaking far more

profoundly than people have ever understood when he said, "We have

got to change our way of thinking." We have got to change our way

of thinking, our way of feeling, our way of interrelating, our way

of caring not only for one another but for the earth itself and

for everything that it stands for. We are making absolutely

obscene clutter of the cosmic surroundings of the earth, filling

it with radioactive satellites, so it is beginning to look like a

used car lot, and we do it with an absolutely pre-adolescent arrogance of ignorance, of not having any sense of responsibility

of what we are doing in a very real way to potentially upsetting

the total cosmic relationship of this single isolated globe. I

feel that this is truly disastrous, and I honestly believe I want

to live to see whether humanity can change its way by the turn of

the century. I think the year 2000 between here and there is

very, very precarious. If we make it to the year 2000, we will

have made such compromises with our arrogance that we will bumble

along for another 3000 years. I think between here and there is

very, very questionable.

I spent a lot of time in the cardiac outpatient department at

Boston University School of Medicine, as well as working in the

medical clinic, and I was much interested in taking care of

cardiac patients along with Jim Hitchcock at Emerson Hospital. I

had been doing electrocardiography ever since I was studying at

Mass. General as a medical student. Emerson Hospital was ready

for a coronary care unit. With Pat Snow and some of the nurses in

the east wing, we designed cutting windows and mirrors to make an

intensive care unit where the nurses could sit and see each of six

beds from where she sat. Then we got American Optical

oscilloscope for cardiac monitoring for these patients, and we

were in business. Charlie Keevil wrote it all up, and it was one

of the key features of Emerson Hospital's contribution to

community health care.