C. Sanfred Benson

Ball's Hill Road

Interviewed August 10, 1983

86 years old

Concord Oral History Program

Renee Garrelick, Interviewer.

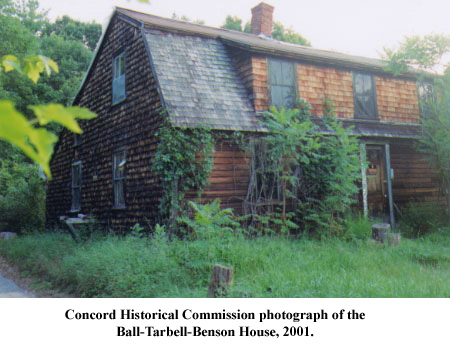

The hand water pump still works, as it has since 1914, and

the land over forty acres of it, has been in Sanfred (Sam)

Benson's family since 1886. He was one of seven children, and

the family's seventeenth-century farmhouse and barn stood as

the sole residence on Ball's Hill Road until the 1970s.

The hand water pump still works, as it has since 1914, and

the land over forty acres of it, has been in Sanfred (Sam)

Benson's family since 1886. He was one of seven children, and

the family's seventeenth-century farmhouse and barn stood as

the sole residence on Ball's Hill Road until the 1970s.

At age 86, Benson has seen the changes come. New homes

are appearing on his road and the large estates along

neighboring Monument Street are being divided up for house

lots. "There were farms all around here, nothing but farms.

Many of them cow farms."

His own family had twelve cows and Benson remembers when

hoof and mouth disease was a dreaded scourge that could wipe

out your entire herd. He finds it fortunate that his own farm

was spared. He remembers veterinarian Dr. Way and later Dr.

Russell coming to treat ailing cows, while Dr. Alderman of

Lexington cared for the horses. And if anyone in the family

was sick, the formidable Dr. Titcomb was summoned.

The farm chores were always there waiting, recalls Benson.

Coming home from school there was the corn to cut for the cows

and milking to be done by hand. "The Lawrence farm on Monument

Street had thirty-five cows and no milking machines." And the

threat of an approaching thunderstorm meant a race to get the

hay pitched into the barn before the rains came. Clover hay

was raised to feed the cows and red top timothy for the horses.

Since then, he says, alfalfa has replaced clover for feed,

hay balers "have really sharpened up the haying." Grain for the

cows and horses was bought at Ben Brown's Grain Store, where

Wilson Lumber is now, he adds.

Asparagus and strawberries led the market garden crops

raised, and Benson remembers getting $2.50-$3.00 a bushel for

asparagus, with three dozen bushels to a box. With World War I,

the price rose to $8.00 a bushel. Strawberries sold for eight to

ten cents a quart and thirty-two quarts were packed to the crate.

Of the two, Benson preferred to handle the asparagus, which

grew well in light, sandy soil. "If the asparagus froze, you

didn't necessarily lose it the way you did with strawberries."

And two to three times a week, the farmers went in to

Boston's Faneuil Hall market, arriving at night to sell their

produce either on the streets or at the commission houses. "By

eleven o'clock at night you had to be off the streets and since

the ride took about four hours each way, you stayed overnight."

After the week's work ended, Saturday night was the time to

drive to town, with the Concord stores open for shopping till ten

or eleven o'clock in the evening. It all made perfect sense,

reminds Benson, since most people had only work horses, not

driving horses. "You couldn't very well make a horse trot into

town after a day's work during the week and most people didn't

reach town until 8:30 on Saturday night."

There was no worry about the snow plow arriving in winter for

the Benson family. "The horses from John Lawrence's farm

would plow us out and if they left six to seven inches of snow,

that made for good sledding."

The trouble though came in the spring. "When the frost went

out of the ground in spring, it left a pretty muddy road." Ball's

Hill Road wasn't paved until about twenty years ago," says Benson,

and he remembers Monument Street before it was macadamized in

1922. A neighbor, Frank Mason, insisted on the macadam surface

instead of a gravel road, says Benson.

Before town water came in, Benson remembers the water coming

from a tank under a stone platform windmill. And before

refrigeration, whatever you wanted to keep cool was put down the

family's spring-fed well. Electricity didn't arrive for Benson

until 1930. "Being the only house on the street, we had to pay

for its installation. The rule was there had to be three houses

on a street for the town to pay for putting it in."

And now the postman delivers the mail along Benson's Street.

For years he walked the lengthy distance out to Monument Street to

pick it up. As he leans on his hoe, taking a breather from his

friendly combat with the weeds and geese in his garden, planes go

by overhead. They interest him. "I've never been inside one," he

says quietly. "I'd like to though." Sam Benson has seen the

changes come.