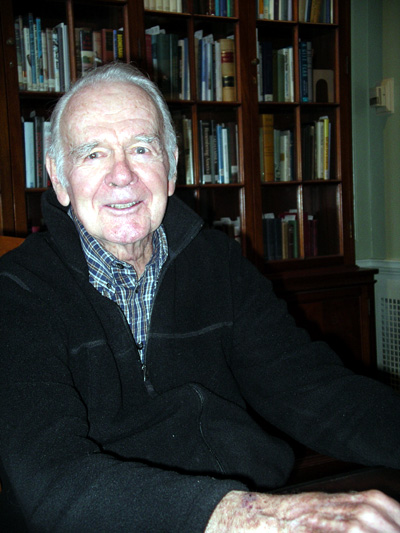

Gordon Bell

Interviewer: Michael N. Kline

Date: April 19, 2011

Place: Concord Free Public Library Trustees' room

Transcriptionist: Carrie N. Kline

Click Part 1 — Part 2 for audio. Audio file is in .mp3 format.

Gordon Bell: …town didn't have a library like this. And, particularly the sculpture and all--.

Gordon Bell: …town didn't have a library like this. And, particularly the sculpture and all--.

Michael Nobel Kline: Well, are you ready to start?

GB: I'm ready to start.

MK: Would you say, "My name?" No, I'll hold this. Would you say, "My name is," and tell us your--?

GB: My name is Gordon K. Bell.

MK: Okay. And your date of birth?

GB: June 7, 1927.

MK: '27. And, well. I don't know. It's an overcast day today, and we need some brightness in the room. Maybe you'd start off--. Tell us about your people and where you were raised.

GB: Where I was--. Well, I grew up actually in Sharon, Massachusetts, which is down between Boston and Providence. And moved to Concord in 1950. When I finally finished school!

MK: I'm picking up the sound of your glasses.

GB: Ah! Sorry. I'm sorry.

MK: This is a really sensitive microphone.

GB: Okay.

MK: Tell us a little bit, some, a memory or two about where you grew up in your earlier life and who your family was.

GB: I'm not--. I--. Incidents I--. I don't know that this is relative to the history to Concord.

Carrie Nobel Kline: But to the history of you.

MK: Okay.

GB: Well, I know, but this isn't a history of me. I thought it was of Concord.

MK: Well it is. We like to set the stage a little bit, but--.

GB: Well, I grew up in a very small town and developed a sense of interest in the town. I graduated from high school in 1945 and joined the Navy and ended up in, the end of the War in Japan, and also ended up on a mine sweeper in the Yangtze River in China. After that I went to college at Colgate. I worked from 1950-'54 in Washington, D.C. for the Office of Naval Research. And while I was there I went to night school and got a Master's Degree in Public Administration. And then. Thanks to the, having a understanding wife, we got married, and I told her I was thinking of going to law school. We did the next year. And I went to the Yale Law School and graduated in 1957 and started practicing law in Boston and moved in to Concord at that point.

MK: In '57.

GB: Yes.

MK: Why did you choose Concord as a place to live?

GB: We were looking for something we could afford. We were flat broke. We were looking in Waltham for an apartment. And Jean's aunt, who lived in Concord said, "You can't live in Waltham. That's no place to live." And so she found us a chauffeur's cottage that was for rent from friends of hers. And we moved into that, and we talked the landlord down from $100 rent to $90 if he didn't do any renovations! So we start at $90 a month in Concord! And we, unlike all the people nowadays, we had to rent for six years before I could afford to buy something. We bought what was then an inexpensive house, and we've made an addition to it and added some land to it. And we're where we--. We've lived in the same house for, well, almost fifty years now.

MK: Umm. What was your particular focus in your study of the law? Public Administration I guess.

GB: Oh, that was for my Master's Degree.

MK: Ah hah. But--.

GB: At night school.

MK: But in law what was your particular interest in law?

GB: I didn't have a particular. At law school I didn't have a specialty.

MK: Ah hah. So you ended up--. What kind of law did you end up practicing?

GB: I practiced with a large firm in Boston and did a variety of things, but ended up as an office lawyer doing commercial and real estate, and other transactions similar to that. I was a, pretty much of a generalist, although I didn't do tax and I didn't try cases. I did try one once, but that's all. I commuted to Boston by train, from Concord.

MK: How long a ride was that?

GB: Well, it would--. Thirty-five minutes. And then there was about a twenty minute walk, which was a good idea. And I was thinking of the changes over the last fifty years. It was very nice when I started, because there was a railroad station. And you could go in it in the morning and buy a newspaper, and warm up by an old stove, and get a cup of coffee if you wanted to. People nowadays have to stand out on the platform. There's no--. No one sells tickets. It's--. Station's closed. But anyhow I used to commute by train.

MK: So, go back to those early memories of Concord. How? What? How did it strike you living here?

GB: Oh, it--. We loved it from the time we moved in. It was just a wonderful place. We had a child at that point when we moved in. he was born in New Haven. And we soon had a second child, born in 1958. And we were--. Emerson Hospital was a very small place then, just a one building really. It was a very nice hospital, but we were shocked to find that they knew nothing about natural childbirth. And we had an awful time finding someone that would even approach the idea of that. In New Haven that was all the rage. I mean that was what you did in that point. It was natural childbirth. And that was an experience.

MK: And the hospitals in New Haven would accommodate that?

GB: Oh, absolutely. Oh, absolutely. Yes, they--. There was totally natural. Husbands could go in and watch if they wanted to. Very avant garde. Hadn't caught up with Concord yet though.

MK: [Laughs.] So what did you do?

GB: What?

MK: How did you solve the problem?

GB: Oh, we had a doctor who said he would let it go as long as he, as everything was fine and--. But he preserved the right to intervene if he needed to. And he didn't have to, so. Worked out very well.

MK: Great.

CK: What is her name?

GB: Hmm?

CK: Worked out for--?

GB: Us.

CK: Okay. I didn't catch your wife's name.

GB: Oh, Jean. J-E-A-N.

CK: Okay.

MK: So, did I understand that she also studied law?

GB: No. No.

MK: Oh, I'm sorry.

GB: No, no, no, no, no.

MK: Ah hah.

GB: She went to Wellesley. And we met in Washington. I was working for the Office of Naval Research. And she was working for the State Department. This was during the Korean emergency thing. Made--. Washington was very active at that point.

MK: Huh. So, you--. So there you are living in the coachman's quarters?

GB: Chauffeur's cottage.

MK: Chauffeur's cottage. Coachman's quarters!

GB: [Laughs] Coaches were before my time!

MK: And what part of town was that in?

GB: That was right up at the Fenn--. Off Monument Street at the Fenn School there's a little road that goes in on Carr Road. It's a dead end road and goes in and dead ends at the river. And we were right on the river which was very nice. Woods all around us, and.

MK: I heard you say earlier that you had taken an interest in the town where you grew up. Was that in the Town government, in the working of the Town?

GB: Well no, I was in high school there. I mean--.

MK: But I mean you still could've been-..

GB: Well, I would go down and shovel snow and, when there was, in the center of town when there was a storm. And when one year, in college, when I was unemployed, the Town gave me a job in the Public Works Department, which I was indebted to them for. And for, the Town also gave my mother a job of Chief, first Children's Librarian. And so we were--. I was always very grateful for all the help the Town had provided. So I've always felt I wanted to help whatever town I lived in.

MK: And that carried over into Concord?

GB: Yes.

MK: Tell us about the development of your civic self.

GB: Well, the first thing I did is I was asked by the Planning Board to be on a study group to study cluster zoning, a way of trying to introduce more flexibility into zoning. In the early '50s, zoning was really a major problem in Concord. When we moved in, for example, the zoning was one acre. And very soon we at least got two acres in. It was--. No one dared to go beyond that. But it was--. It's too bad we didn't. I mean you--. It was--. People were worried about--. We squeaked that through though. And after being on that study group, I was asked to join the Planning Board, and I was on the Planning Board for I guess the five year term. I was Chairman one year. We had a lot of subdivisions at that point. The one thing I--. Among other things, I'm very pleased that I was able to get a height limitation in town. We had had no height limitation, and I was so concerned with the Milldam down here, and what would happen if people started building unlimited height. And I think that was an important contribution to preserving at least the Milldam and the town as we knew it. I think high rise buildings are one of the first things that disrupts a suburban community and changes its character. After that--.

MK: What did you get it limited to?

12:55

GB: Thirty-five feet, which is just about what the existing buildings are, a little over what the existing buildings are. But you put, that's possible three, but it's squeezing it. Two's better. But anyhow. Let's see. Subsequently I was an associate on the Board of Appeals, Zoning Board of Appeals. Oh, excuse me. My first position in Concord was on the General Building Committee. John Bemis put me on the General Building Committee, and our responsibility was for planning and contracting for all public buildings. And I think the biggest thing that we did when I was on it is we preserved the Veteran's Building, which people wanted to tear down, and which is now a very active part of the theatre in the Concord, here in the center of Concord. I also started planning on development of the Middle School. And after the General Building Committee I went on the Planning Board. Excuse me. Subsequent things I've done in Town is--. Oh, I was head of a Long Range Plans Committee at one point. And I couldn't get it to come out the way I wanted it to, so I didn't finish that up.

CK: What do you mean?

GB: I was on various study groups. I studied—for the Town. I studied housing at one point. I studied the dump situation, where that could be, should be, how we should handle it.

MK: What did you come up with there, because we need models, good models now to go by.

GB: Yeah! Well, we had several ideas, and nothing has been implemented. It's still where it is. But we forcefully said that where the dump is now should--. It abuts the Walden Woods, Walden Reservation. And I think we made the point that it should be part of the Walden Reservation eventually, and I still, form time to time speak up on that when people have ideas of things to do with it. But it hasn't been moved, and several places that we recommended have disappeared, and I'm not sure what's going to happen at this point with that. Other things I have done in Town, let's see.

MK: What about--. This was for the location of the landfill, or?

16:05

GB: Yeah. Yeah.

MK: Or what sort of a dump, or--?

GB: Well, it's now called the Sanitary Landfill. It's--. But I still call it a dump, because that's what it used to be. Actually, when I moved into Concord, the dump was where the high school is now. And we used to take our stuff there and you put everything, trash and, all kinds of trash, except garbage. Garbage was picked up by people that had pigs. And, but you sorted it out. You didn't have paper in it, but. You'd take it down to where the high school is now and it was burned. And it was usually burning. It burned continuously. It was--. People can't believe that the site where the beautiful high school is was once a dump. But anyhow. Dumps are a problem in Town. And our Sanitary Landfill is for leaves and brush, and they do take some paint in a little shed. But it's not for general trash. We have general trash pick up now, if you want it through the Town.

Other things I've done. I've--. I am the--. I'm on the--. I'm associated with the Land Trust in Concord. And the Land Trust has been a major force in conserving open space through private contributions. And I have worked with them through their subsidiary, the Concord Open Land Foundation. We don't make any distinction. We meet together and operate together. I have helped the Land Trust for years with land transactions. Oh, I retired. That's when I retired I was able to do this. I retired and then I was able to work for the Land Trust doing--.

MK: In what year did you retire?

18:22

GB: I don't know.

MK: Or decade!

GB: [Laughs] I forget. Late . . . .

MK: You've probably been so active that you didn't notice when you retired.

GB: Well that's true. I didn't. I didn't. But anyhow, it has been quite a while now. It's been over twenty years. Yeah. And I still actively work with the Land Trust on land transactions. I particularly write conservation restrictions, which we get from private individuals, and which we have used between the Town and the Land Trust to help support each other's activities. We bought a big piece of land. We needed help financially. The town helped. We gave them a conservation restriction on the land. We're--. I'm right now in the process of doing just the opposite thing. The Town is going to buy a piece, and we're going to contribute our funds through a conservation restriction.

MK: What's an example of a conservation restriction?

19:39

GB: Well, the typical--. The conservation restrictions really started out, and largely are now, a marvelous way for people to conserve their land and get a tax advantage. You can have--. If you have say five acres of field that you have always--.And basically this has been done by people who have lived in Concord all their lives and, or more, or other generations, and would want to preserve what they've always liked. And what you can do is you can take that five acres and put a conservation restriction, which, in effect is an easement. And it says that you cannot do anything with your land, except keep it as open space, or maybe agricultural space. Or maybe do some timbering, but with, under forest plan. But it's basically you can't develop or put any structures on your land. And if you do that in the proper way, and it's approved by the Select-- Natural Resources, the Selectmen, and the Secretary of Environmental Affairs of the Mass, Commonwealth of Massachusetts, if you get all those approvals and it's done properly, you can get a deduction from your income tax for the value of your, the gift of this. In other words the development value of the land can be taken as a tax deduction. And this makes it very attractive to certain people in certain circumstances, so that this has been a marvelous instrument used by the Land Trust and the Town. Some people like to give their land to the Town instead of the Land Trust and that's fine. And I have also helped the Town with their conservation restrictions. In fact I draft all their conservation restrictions at this point. And I work with the Natural Resources and the Town on that, again, without compensation, in sort of a strange fashion. I'm not counsel to the Town, but I can work, have done these and work on these. So I'm still actively engaged with the Town in that.

MK: The Land Trust dates back to roughly--.

22:25

GB: Back to, oh it's about, just about the time we came to Concord, the mid-'50s.

MK: Okay.

GB: It was set up by a number of the prominent people in Town, David Emerson, Stedman Buttrick, etc. And it's a very--. And we've acquired a great deal of land. And again, it's becoming more and more difficult, because land now is very expensive to acquire. We have been fortunate to have land come, become available where there are people that can help contribute to that. And then we have some basic contributors. We also ask our members to contribute to land acquisitions. And we have several that have cost two or three million dollars, so that some are pretty big. We still like to receive land as gifts, but one is not always able to do that, and land owners aren't either, so we try to keep posted on what's going on when something comes up that's important. And we either do it with the Land Trust or with the Town, and put all our energies together to try to conserve as much of the open space in Concord as we can. Our particular interest now is to preserve agricultural aspects of the Town, because that's fast disappearing and used to be really the character of the Town was rural, but, a hundred years ago, easily. But anyhow, that's what I still do, and--.

MK: Since its birth in the '50s, can you tell us roughly how much public land, or trust land—

24:40

GB: Oh, dear.

MK: I mean is it hundreds of acres?

GB: Oh, it's a thousand probably.

CK: What is?

GB: A thousand probably. I'm not sure of the figure. I could get you the figure.

MK: Put that thousand in a full sentence, will you? Say--.

GB: We have probably preserved through acquisitions and conservation restrictions probably a thousand acres. This is not as impressive as it sounds, because a lot it is wetlands that can't be built on anyhow. And so that's why it's a figure I don't like to use, because it sounds big, and if you--. It would be--. Probably a half of that is buildable land. Again, people give us land they can't use. We can afford to buy land that can't be used for building. But we have to be ready for, to also take on other land.

MK: Well wetlands, of course, are terribly important.

25:48

GB: Terribly important. Yes.

CK: What was that now?

GB: And Concord is, has three rivers in it, and a lot of streams. It's a wet--. Used to—. The glacier left it as a lake bottom actually, but. So we have--. The Sudbury River and the Assabet River flow together and form the Concord River, right over here on the other side of Concord Academy. And the Concord River is of course where the North Bridge is. So, anyhow I have tried, trying to help. Oh, I also was on the Concord Art Association for a number of years as treasurer.

MK: Concord Art Association?

26:45

GB: Concord Art Association. I have done some painting and sculpture. I was also for a number of years involved with the National Park Association, working with the National Park to have a Friends organization. I was president and treasurer of that, off, different times, but those have been my primary activities I guess in Town.

MK: Can you talk a little more about the Park project or projects?

GB: Well, the National Park is probably the best thing that every happened, one of the best things that, probably the best thing that ever happened. Well, no, there are other things too, but one of the best things that ever happened to Town, because it preserved the land on the other side of the North Bridge where the Buttrick house is, which is the side where the Minutemen were when they came down on April 19 to meet the British. You said you were not aware of April 19, so I'm working my way into it. And that's our famous day in Concord, when the Minutemen engaged the British. Unlike Lexington, we actually fought the British and killed a number of British soldiers. Several are buried down at the North Bridge. But the National Park preserved that, and they have rebuilt the North Bridge once. The Town has rebuilt it a number of times. The North Bridge has been washed away numerous times, so the original is not there! It's a good reproduction though. But the National Park has preserved also land all the way out Lexington Road, to Lincoln and on into Lexington. So it has, I forget how many acres of land, and it has, is trying to restore the Battle Road as they call it. The Battle Road. The Battle in Concord started with the Concord Fight. We don't call it a battle. It's the Concord Fight at the Bridge. And then, as the British left town, the Minutemen from all over gathered and fought them all the way back to Boston as they marched down the Lexington Road and the highway. And so the Park has bought a number of houses and has torn them down. It has restored authentic houses and barns. It's really--. It's--. Now I'm sure that they have something over a million visitors a year to Concord, so that it's very important. But the fact it has preserved so much of Town is so important.

Fish and Wildlife Service also has preserved a number of the marshes along the river and has a large impoundment down, further down on the other side of Monument Street. So the, we've had help from the federal government in a number of, or in those two areas, preserving Concord as an open, as open as we can have it. There's still some pieces of land that we should have, and hopefully some day we'll get them. Whether we can afford them anymore or not, I don't know either, but one way or the other we are alert to the possibilities all the time. And if you know Concord you'll find that there's a great deal of woods and open space. Oh, the Emerson's originally owned Walden Pond, and they gave that to the state, so Walden Pond is part of the state, state land. We own a big piece of land beside that, which was given to us, but--.

CK: We?

GB: Hmm?

31:30

CK: We being?

GB: The Land Trust. Excuse me. So anyhow the--. Land preservation has I guess been my real interest. I've spent a lot of time on it. Still do.

MK: Has it been a happy working arrangement between the Town and the feds in both of those areas?

GB: In the National Park, they got a lot people upset, because they bought their property, their—wanted--. Well they had a right of first refusal, but they would buy property, and then give people a life estate if they wanted to stay there. Politically, these, a lot of people were unhappy with giving up their family houses and land and particularly when their life estates ended they didn't realize that they're made this deal to, it would be Park land after they were gone. Politically they've tried to create problems out of that, as you can imagine. And then the Town has to pay attention to all problems of all people, and has paid attention to is, but it has become, it's pretty well faded away now. But at one point there was a lot of objection to the Park.

MK: Would this have been expressed in the Town Meetings?

33:17

GB: Well, we did—weren't really occasions to vote on that sort of thing, but there was the unfairness of taking our land by the federal government. You know that sort of thing always creates problems, tensions. But anyhow it's, that's pretty well behind us now.

CK: Well what was the process?

GB: Hmm?

CK: What was the process?

MK: Of taking--.

33:45

GB: Well the process, the federal government laid out the lines for the Park, the bounds for the Park. And within those bounds the Park was authorized to purchase, take by eminent domain or otherwise get all the land within the Park boundaries. So--.

MK: Was eminent domain ever used?

GB: Yes. Yes.

MK: Oh, it was.

CK: What's that now?

GB: I think it was, but not very often. Usually it was, they worked out arrangements with people.

MK: Can you say that in a full sentence? Eminent domain--?

GB: I think it may have been used, but I think the Park tried to use it as little as possible. They basically tried to make deals with people to purchase their property at a fair market value. But anyhow, that's--. You can feel the problem though, if you ever have been involved with city planning or redevelopment or anything.

CK: You talked early on about being part of the Long Range Planning Committee but having aspirations that maybe weren't uniformly agreed to.

GB: No.

CK: It would be nice to hear more about your views.

35:10

GB: It wasn't aspirations, it was the form of, that the plan should take, and that was--. I, we have had oh at least three or four different long range plans, and none of them tie together at all. And I always thought that rather than just coming up with a plan, you should take distinct areas and recite the history once and for all, so that you've remembered what you had done when. And then you could just add to that when you wanted to do a new plan. In other words, you shouldn't have to start form scratch each time and you should do schools, you should do highways, you should do parks. You should do that sort of functional things. And the-. I couldn't get anyone to agree to that, so they did what's always done. When I left they hired a consultant, and he just put together something that mushes all the stuff together in this long range plan. We've had several of these. We probably will still, and it always has been--. It hasn't built historically the way I think it should've. However, when I was working I didn't have the energy to spend that much time to do it myself!

MK: So continuity is the missing ingredient it sounds like.

36:50

GB: I think it is. I think that any time you have some issue come up, you really ought to know the background of how you got to where you were, and what people had done in the past. I have a strong feeling of that. But anyhow, that's long gone.

CK: Well it's long gone, but it's important to think about how to do this long range planning. I'm interested--.

GB: I know it. I know it. I still think that's the way it should be done, because you then have something that you can work on every time something comes up. And when issues come up you don't' have to go back and try to resurrect when did we do this, why did, how did we do it, and all that. But anyhow. More historical presentation than what someone thinks might someday be done. Anyhow.

MK: Well, it sounds like a reasonable justification for the Library to be doing this project is to capture as much of the collective and professional memory of the Town as possible. I think--.

GB: Well it doesn't do any good if it isn't available and people know about it and you can access it.

MK: Umm hmm.

GB: I mean archives are not the most useful thing.

CK: How would you have it--? What are we talking about, to start with, to start with? What's the "it?"

38:22

GB: Hmm?

CK: I don't think he can hear me very well. Maybe you could--.

GB: yes, I can. I can hear you all right.

CK: Okay. I've--. A lot of people can't hear me.

MK: I can't hear her very well.

GB: Well I have s--, but I can hear her all right.

CK: What is this "it" we're talking about?

GB: You've lost me now. We were talking about your project to get people's memory of the past I guess. And--.

MK: And you said, "Just for archival purpose it's not always ultimately useful."

GB: No. No. I mean if it's buried in the archives someplace it's--.

MK: So how could the material become more useful, do you think?

39:33

GB: Well, I have talked about the background of land preservation. Others probably could talk about the certain cultural aspects of the Town, like the Concord Players, the Art Association, the churches, social organization. But if you had something about volunteer organizations in particular areas, you could perhaps-. I don't know whether you can-. I don't know. If--. Everything is dynamic and moving, but I just don't--. I guess I'm getting back into my long range plan thinking! I think these histories of peoples' experience during the War is interesting. That's interesting. Someday it'll be of interest to someone. But that doesn't serve a public purpose in a way. Although one of the nice traditions that I hope the Town always follows, and that is that we raise the flag that's in the center of Town, the big, high flag pole. The flag is always raised to half-mast when a veteran dies. And I think that's one of those nice things to commemorate. And we have a real sense of our, of history in Town, and you see the flags up today from, left over from the parade Monday. But--.

MK: Tell us about the parade, and tell us about the celebration of this famous day in April.

42:10

GB: Well, it's unknown in many parts of the country like West Virginia! We consider it the most important point of the American Revolution. Well it was. It was when the first time the British were met, met enemy fire; it was tremendous. Well when you go back in to the history to realize that you're going to be come down as farmers with your rifles and whatnot and meet the British Army, which was then the largest force in the world, the Navy and the Army in Britain. But anyhow, it was a beginning of a revolution. And after, there were Minutemen killed at the Bridge. Again, it was a skirmish at the Bridge. I can tell you what the forces were, but I--. After April 19th, well that was--. And the--. Then the British evacuated Boston the next spring, and the War really left Massachusetts at that point. But Concord initially used to mark the occasion. And then it was the only one I think that--. Oh well, maybe Lexington did. But, it was really a local thing. And April 19th is, I think now is, well should be recognized nationally as one of the important, the first time Americans fired at the British, fought the British, started the whole Revolution. At the--.

It's interesting historically, at the time, the British government, well the Governor and the British control broke down when they were holed up in Boston. And the towns continued to run themselves the way they always had historically. I mean we were perfectly able to raise our taxes, do our things. And Concord did. We were one of the focal points of the Revolutionary Councils that met with the British, during that interim. But I guess what I really wanted to say was that Concord preserved the tradition of a parade, or some marking of the occasion. At the hundredth anniversary in 1975, that was a huge event. And that really kicked it off as a major event. I believe President Grant came, and--. 1875, is that right? No. Well, Ex-.

MK: Ex-President.

GB: Yeah. But anyhow. That kicked it off as a big event, and it has been a major event in Concord since. And we have our big parade every year. We--. It's a very nice ceremony down at the Bridge. The British Council comes out and puts a wreath on the grave of the British soldiers. Taps are played. God Save the Queen is played. And then the Concord Artillery, which was formed in 1775, fires their cannon. They have some horse-drawn cannon. If you haven't seen their cannon, it's worthwhile. It's--.And that makes a huge sound, and it's lovely. But anyhow.

MK: But there's no reenactment of the--.

46:37

GB: No reenactment.

MK: Of the fight.

GB: No. They do that in Lexington. And in Lexington they never fought back against the British. The British killed Lexington people, but the Lexington people didn't fire on the British at the Green. On the way back they joined in with the others. By the way, Paul Revere never got to Concord. Dr. Prescott gave us the word the British were coming. That's another little tidbit of history that's fun. Paul Revere and Dawes, who had met up outside of Lexington, were riding to Concord. And they met this Dr. Prescott this Dr. Prescott at about 2:00 or 3:00 in the morning. He had been seeing the woman who later became his wife, I might say. But anyhow, he was out late that night, and he joined them. A British patrol intercepted them. And Prescott, knowing the land, jumped a fence with his horse and got away, and brought the word in Concord, "The British are coming." Revere was captured on a site out on Lexington Road, so he never made it, despite what Longfellow said. Anyhow. And, oh, we still at midnight, Dr. Prescott still rides into Town and gives the word that the, to the Town that the British are coming with--. That's another little historical thing.

48:18

We don't have a re-enactment. One of the things the Park doesn't allow re-enactments on Park land, which I think is an interesting phenomena, an interesting policy. But I think it's a good one. I mean you don't want people reenacting Gettysburg on the land at Gettysburg. You don't want people reenacting other battles. It seems to me it's--. If you haven't thought about it, you've--. The more you think about it the more you realize, it's a good policy.

MK: Do you think such reenactments are in poor taste, or that they stir up bad memories, or that there are bad karma, or--?

49:15

GB: No, I think--. I mean if people want to do them, I think they're fine. But I think to do them on the actual land where, which has been dedicated, as Lincoln said, hallowed beyond whatnot, I don't think it should be disturbed. I mean I like re-enactments. I think they're fine. And people love them. And I would not say no to them. But I think the policy of not allowing them on the actual sites where it happened is probably good. Think about it.

CK: Well you've obviously thought about it a lot more than we have. I'd like to hear--.

GB: I have. I have. I first was appalled by it. The more I've thought about it over the years the more I realize it makes good sense, good sense.

CK: From a non-violence standpoint? Ending war? Is that part of it?

50:11

GB: No. As Lincoln said of Gettysburg, it would, it's hallowed ground, and they have dedicated it far beyond our power to add or subtract. For people to go out and play war where war actually happened, I don't like the idea of.

MK: But that was an acquired opinion. You started out at the other--.

GB: Well I've--. Never heard it. When you first hear something strange you--. Yes, I've. The more I've thought about it, the more sense it makes to me.

MK: Very interesting.

GB: Yeah. Yeah.

CK: So midnight, this being Tuesday and yesterday having been the celebration of Patriot's Day, so Sunday night at midnight--.

GB: We celebrated it on Monday, which is the new State way of celebrating holidays, Monday holidays, to give people a three-day weekend. When I first came to Concord, Concord had its parade on the 19th, no matter when, what day it was. I think we didn't do Sundays, but anyhow, we used to--.That was our day, and we did it, and the rest of the world didn't do much of any--. Lexington did. But Lexington and Concord have preserved that. It's slopped over into convenient Monday holidays now. So yesterday they--.They still mark the 19th. They. The Battery has, fires a salute on the 19th still, down at the Buttrick grounds at some 6:00 o'clock in the morning or something like that. But, so that the tradition of something, some noting is done. It's a shame though that you can't do things on the real days. But Washington's Birthday and all that sort of thing is gone. Anyhow.

MK: Well this is all fascinating to me.

52:34

GB: Well, this is history. But I—I mean.

MK: But it's more than history. I mean it's the politics or history. It's the public struggles over history. It's fascinating.

GB: Yes. Yes. Yes.

MK: In West Virginia of course, we have reenactments all the time. And--.

GB: Civil War?

MK: Yeah, Civil War stuff.

GB: Yeah. Right. But do you do them on the actual sites where they?

MK: Well, it would--.

CK: Some of them.

MK: Some of them. Yup.

GB: Yeah. But serious ones, serious sites? I mean I don't know.

CK: Yeah.

MK: yeah. Yeah.

CK: Yeah.

MK: Bang, bang stuff. Bang, bang and fall dead stuff. I don't know….

GB: Yeah. And that's--. It's--.There's something wrong about that, on the actual place—

MK: Playing—

GB: --playing.

MK: As you put it, playing war where real war has been fought.

GB: Yeah. Yeah.

CK: And people died.

GB: Yeah. I mean you don't go to the trenches in France and play war.

CK: You pray, if anything.

GB: Yeah. You don't reenact D-Day and play at those things. Anyhow. One man's opinion.

MK: No. I think it's at the core of all kinds of public history events and projects. And it's right on.

GB: Umm hmm.

MK: You mentioned a while ago, volunteerism in Concord. Has that been pretty significant?

GB: Our whole Town government is run by volunteers. Our Selectmen are elected. And I think their salary has gone up. I think it's $75 a year or something. But they're the only--. Outside of Town employees--. We have a Town Manager, and Town employees are paid. But the Town is really very much run by volunteer committees. We have a Finance Committee, for example, that prepares the budget, again with help from the Town Manager and the Treasurer. But they present the budget to the Town Meeting. They make recommendations on every expenditure of funds by the Town; the Finance Committee has to make a recommendation to Town Meeting. We have a committee that runs the Natural Resources, in other words the open space in Town. That's a, has a committee that runs, has an employee, but they have a committee that sets the policies and does the things. Committees are appointed by the Selectmen, but they really are quite independent. They're not, they don't kowtow necessarily to the Selectmen. It's not an obligation felt. They're independent, and they do. If there--.We have a Public Works Committee that runs the highways, the sewers, the water. We have a Light Board that runs the--. We have a Municipal Light Plant in Concord, which is unique, probably to other, in other parts of the world, but we--.

MK: All volunteer?

56:15

GB: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. And we have a Recreation Committee. We have people that serve on the Historic Preservation Committee that reviews Historic Districts, changes within those. We have very tight Historic Districts in Concord. We're--. You can't change the color of your house without getting permission, so. Not the whole Town, but certain particularly historic areas. In other words, the Town functions through volunteer committees. And each of these committees presents its word articles for the Town, what they think ought to be done. Justifies, argues for them. School Committee's elected. Selectmen are elected. But otherwise it's all volunteers. It's--. So, lots of people spend lots of hours on Town affairs.

MK: Does that figure in in-kind contribution if you're trying to raise money from a, say a foundation, or an endowment somewhere?

57:33

GB: I'm not sure of that.

MK: You know what I mean?

GB: Yeah, I know.

MK: In-kind contributions?

GB: Yeah, I--. No, I don't. Oh, I think some grant proposals do ask for that, but you know. I think we have, there have been grants where we've asked for that, but who knows how much time one volunteers and what it's worth. But anyhow, there is a--. And this is a structure that has existed since the Town was founded. I mean we--. It used to be--. By the way, Concord is, you should know, is the first community in Massachusetts to be above Tidewater. We were the first Inland town in Massachusetts, if not--. I think it's Massachusetts. I shouldn't enlarge it. We were founded in 1635, which is five years after Boston, and fifteen years after Plymouth, so that's pretty early. So, we had a long history prior to the Revolution. And the, I think having that period of time is what built of the feeling of being able to be independent and running yourself. I mean, originally the Town and the church were intertwined—were the same. I mean they would have the church service, and then they would have a Town Meeting! And obviously everyone that was a member of the church was a member of the Town. But from the early days, we had Town Meetings, with laid out roads. That was one of the first things they did. They laid out roads, for example. And the Town Meeting allocated land when they had the different divisions of land in town, so that the self-government is just born within the people who've always lived here. And 1635, 1775, divided by twenty for generations in those days, that's a lot of generations.

1:00:29

So you can see that the people who went down to the Bridge were long severed from their original English land. I mean they had grown up on a frontier. They were different people. Still British. I mean they were. All wanted--. No one wanted to be anything but British, but they did develop during that period into something else. And I think that time is always worth focusing on.

MK: What? Six or seven generations?

1:01:03

GB: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. 1635. 140. Seven generations, at least. Anyhow. Anyhow.

MK: And we've interviewed people in this room who trace their lineage to that period, and--.

GB: You can get back pretty far, but.

MK: Back pretty far.

GB: Yeah.

MK: I'm wondering--.

GB: Did you interview Sted Buttrick who recently died?

MK: No.

GB: That's a shame because--.

MK: Well the previous oral historian may have interviewed him—

GB: Yeah.

MK: --done that interview. I don't know. [Transcriptionist's note: Renee Garrelick interviewed Stedman Buttrick on April 17, 1997. See http://www.concordlibrary.org/scollect/Fin_Aids/OH_Texts/Buttrick.html]

1:01:43

GB: Because Sted Buttrick was--.I forget how many there were, but the original leader of the Minute, Concord Minutemen, who led them down to the Bridge, was a Buttrick. And so he was a direct relationship.

MK: Sorry we didn't get to talk to him.

GB: Yeah. Yeah. But--.

MK: Well I--.

GB: We have. We have people down the road from us who've farmed their land. And it has been in their ownership for, oh dear, several hundred years. Yeah. . . . Yup.

MK: Well I'm sitting here and I'm thinking how fortunate this Town has been that you and your wife decided to settle here, when you did.

GB: Well my wife has made more contributions to the Town than I—to civic organizations than I have.

MK: Wow.

GB: She has really organized ongoing organizations.

MK: But what a gift for a town to have access to your, not only your ability, but your passion for history and your passion for community and--. I'm just wondering what it's been like for you without that lineage that seems so significant to many of the old families.

1:03:12

GB: Oh, I have my lineage too, but.

MK: But not here.

GB: Not here, no. Our fam--.

MK: So how did people treat that? Did you--?

GB: My family went west to Ohio. My mother and father came from Ohio, and so we went west and then came back east.

MK: But socially, politically, has that been a significant dynamic for you, coming in as an outsider?

GB: I don't believe so. No. No, I don't think so. No, I don't think so. I mean, I think those feelings were--. When we first came to Town there was a much different feeling than there is now. I mean fifty years ago I think that sort of thing was much more pronounced. There were social leaders of the Town and whatnot.

CK: What sort of thing was more pronounced?

GB: Well, the--. There were certain recognized historic families and leaders that were more recognized. I mean I don't think now that's true.

MK: But when you came?

1"04:30

GB: Yes, I think there was a different--. Yeah, I think so.

MK: We wouldn't want to call it snobbery, but--.

GB: No, there isn't--. No, it isn't snobbery. No. No.

MK: But what would you call it, the treatment of newcomers?

GB: I, I , I think everyone--. I mean I think you're accepted for--. I mean you didn't immediately get into the social circle I guess. But, I don't--. I shouldn't say that. I don't--. Struggling. I don't--. I think Concord has always been very open and democratic about that. There's obviously a--. People--. Well, you used the word snobbery. There's some of that, but I don't think it's been a, it's a real factor in Town, certainly not now.

CK: Who lives here now? What kind of diversity exists if any, and how has that played out?

1:05:43

GB: Diversity. I think increasingly the Town has become professionals. The real estate prices have made it an expensive place to live. I think the ordinary, whatever that is, working person--. Well, for example, I don't think--. I think there are a few who've, whose parents lived here and who inherited their parents' houses, but I think most of our Police and Fireman no longer live in Concord. And that makes good sense, because they can't afford it. Just plain can't afford it. We--. There are certain people who've made various efforts to introduce low-income housing and that sort of thing, but it's a--. It's not significant. I think Concord's probably become more upper-income-oriented now than it was fifty or a hundred years ago certainly. But this is--. This is the land cost, the land. And one of the problems of becoming a successful town is that this happens! Becomes a place where people want to live.

MK: Good schools.

1:07:29

GB: Good schools, supported by, without difficulty, by the Town. Spends money on things that are necessary. Roads are kept up reasonably well. Lot going on socially. You can join all kinds of activities in this Town. Incredible. You could go out every night to some committee meeting or something. There's--. And there's great choices of what you want to do.

MK: Well this has been absolutely fabulous. What should we ask you, in closing, that we haven't approached yet?

1:08:17

GB: Well I was thinking about this before I came down. And I think that the most remarkable thing about Concord is that in the fifty years that I've, over fifty years that I've lived here, I don't think it has changed that much. I mean physically there's been a lot of infilling of houses and land developed. But I think when you visit the center, and North Bridge and whatnot, the Town hasn't changed that much. I think the Town is still well-governed. I think it's fiscally sound, has a good school system. Probably better than when we came! I'm sure it is better! We came just at the time when the post-War generation was creating more and more students, and most of the schools had been built since I was, I moved into Town. Most of the schools.

MK: Well, the preservation of the built landscape--

GB: Yes.

MK: --is in large part due to your restriction on how, well the thirty-five feet.

1:09:39

GB: Well no, the Historic District Commission is the basic. That the real control. The zoning was. Mine was a small contribution, but the Historic Districts is the real control, now. I mean that controls everything. It's really frightening, when you look at it! What you can't do without permission! But anyhow, people have accepted it. But I think basically the Town is in good shape. It's a good Town. It's a good place to live. And it's a good place to bring up children.

MK: Is there anything else?1:10:28

GB: And I'm not a booster. I'm not a booster-type person either.

CK: So Concord--?

GB: I'm trying to set forth fact. I mean I'm not selling it. I'm--. That isn't my field. Public Relations is not my big forte. Anyhow. Is that what we need? Or want? Or Got? That's what you got.

MK: That's what we got.

GB: That's what you got. I don't know what you need!

MK: No, this is--. I think it's outstanding.

CK: Wonderful.

MK: Outstanding. Thank you so much.

1:10:59

GB: Haven't you gotten a lot of this history from other people?

MK: It doesn't matter if we have or haven't. What's--.

END OF TRACK: 1:11:06

NEW TRACK

MK: All right. Okay.

GB: I forgot to tell you that one of the things that I think is most significant. And that is that almost all the best things in Town have been gifts of people in town. This library, for example, was a gift. The Emerson Playground over here, which is our really big playground--.

MK: Oh, oh. Okay.

GB: Was a—

MK: Yeah, go ahead.

GB: Was a gift of the Emersons. Walden Pond was given by the Emersons to the state. The Estabrook Woods, which lies between Lowell Road and Monument Street, was given by three or four prominent people in Town. What else? Well. Oh, the Great Meadows was a bargain and sale with the Fish and Wildlife Service, but it was largely given by the man who set them, set up these impoundments and whatnot. I should be able to go on, but almost all--.

MK: But it makes the point.

GB: These are physical things of their organizations or run by people, and gifts and whatnot. But. The people who've lived in Town have been very generous to the Town. Oh, the hospital was given to the Town. Again, I think the Emersons originally. Very important. And, but that's what I wanted to say. It's an aspect of it that's important.

MK: So it's almost like--. That gives it almost a, what a family feeling or something--

GB: Yes.

MK: --of the shared heritage.

GB: Yes. Oh and the Town--.Oh! Yes, the Town Forest was given to the Town, which is on the way to Walden. And all of the land going toward Walden, which is, well it has a school on it now and the Courthouse and whatnot. All of that land was given to the Town for a Poor Farm, by--. Oh, I should know his name, but it slips me right now. But all of that land was given to the Town. And the Town has used it for other purposes increasingly, which is too bad, but has preserved the principal. And--. Anyhow, I think it's unique that most of the large things in Town have been gifts of people. As I said, now the Land Trust is not one person, it's numbers. But anyhow. Yeah.

MK: Umm hmm. Beautiful.

3:13

GB: I thought sh--. Thank you.

MK: Thank you.

END OF TRACK SECOND TRACK: 3:19:30

END OF RECORDING

Back to the Oral History Program Collection page

Back to Finding Aids page

Back to Special Collections page

Home