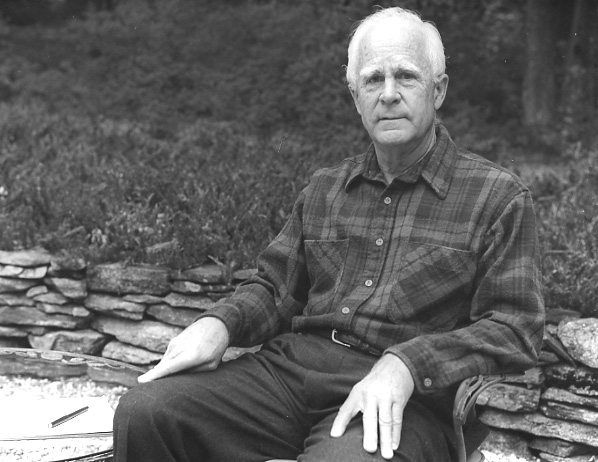

William Thurston

GenRad President 1972-1988

141 Bolton Road, Harvard, MA

Age 72

Interviewed October 15, 1993

Concord Oral History Program

Renee Garrelick, Interviewer.

I started with GenRad in 1941. I'll go back to the history of the Company before I was there, which covered a span of 26 years from 1915, when it was founded, to when I arrived in 1941. In 1915, the word radio was a new word. As I understand it, the word had been coined by international treaty only a few years earlier. When people used that word, they thought of Morse code and the Titanic sending their message that was not responded to, there was no voice communication by radio and the vacuum tube was not yet in use, although I think it had been invented. The founder of the Company was a man named Melville Eastham, who originally came from Oregon. He did not have a college education, but he was very bright, very interested in radio, in technology of all kinds from a practical innovative standpoint. He came by way of New York into Massachusetts and was partner in a company called Clapp Eastham that manufactured X ray equipment back before 1915. He noticed that there were more orders for their coils from radio amateurs than there were from the X ray users. He got the idea that radio might become some day an important industry. So he founded a company called General Radio Company to manufacture precision test and measurement equipment for the radio industry, which at that time really hardly existed. It was seven years before the first radio broadcast, which occurred in 1922. And it was before the home radio receivers existed. There were no radios in livings rooms in those days. Inasmuch as he anticipated fantastic and unprecedented growth in the electronics industry, which is what the radio industry became when Electronics Magazine put out its first issue in 1930 and called itself "Electronics," I think he has to be credited with a lot of foresight. He was very interested in photography and in the Karl Zeiss Works in Germany, which made precision photographic equipment. He had a workshop in his basement with machine tools and measuring gauges and measuring blocks. I think measuring was his hobby.

I started with GenRad in 1941. I'll go back to the history of the Company before I was there, which covered a span of 26 years from 1915, when it was founded, to when I arrived in 1941. In 1915, the word radio was a new word. As I understand it, the word had been coined by international treaty only a few years earlier. When people used that word, they thought of Morse code and the Titanic sending their message that was not responded to, there was no voice communication by radio and the vacuum tube was not yet in use, although I think it had been invented. The founder of the Company was a man named Melville Eastham, who originally came from Oregon. He did not have a college education, but he was very bright, very interested in radio, in technology of all kinds from a practical innovative standpoint. He came by way of New York into Massachusetts and was partner in a company called Clapp Eastham that manufactured X ray equipment back before 1915. He noticed that there were more orders for their coils from radio amateurs than there were from the X ray users. He got the idea that radio might become some day an important industry. So he founded a company called General Radio Company to manufacture precision test and measurement equipment for the radio industry, which at that time really hardly existed. It was seven years before the first radio broadcast, which occurred in 1922. And it was before the home radio receivers existed. There were no radios in livings rooms in those days. Inasmuch as he anticipated fantastic and unprecedented growth in the electronics industry, which is what the radio industry became when Electronics Magazine put out its first issue in 1930 and called itself "Electronics," I think he has to be credited with a lot of foresight. He was very interested in photography and in the Karl Zeiss Works in Germany, which made precision photographic equipment. He had a workshop in his basement with machine tools and measuring gauges and measuring blocks. I think measuring was his hobby.

When he founded the Company, the First World War was going on but ended shortly thereafter. Then in the early 1920s was the first radio broadcast, and the industry took off. Everyone was buying parts and putting together home radios and listening to sports games and newscasts and things like that. His three financial partners who owned the Company were interested only financially. They wanted to go into the home radio business. Eastham didn't want to, because he thought that home radios would become very competitive, dog-eat-dog, cheap products, and that turned out to be correct. I remember when I went off to college in 1939, I bought a 4-tube radio from Sears for $5.95. He also thought that industry would spend a lot of time litigating patents, and it did. It spent most of the time in court -- RCA, GE, all those companies. So he didn't want to do that. So what do you do when all your owners disagree on where the company is going? Well, he just happened to have hired in 1917 an independently wealthy man who was the son of the treasurer of the Sacco Lowell works, which made all the textile machines for Lowell and Lawrence. This man had radio amateur for a hobby and didn't have to work, but in 1917 he wanted to do something for the war effort and so he joined General Radio, thinking he could be of some use. It quickly turned out that he was of more use in administration than in the laboratory, and he became the chairman of the board. His name was Henry Shaw. To solve this problem of what direction the Company should go in, Henry Shaw used his personal resources to buy out the three financial partners who wanted to do something else, and they left, and we never heard from them again. So Henry Shaw and Melville Eastham owned the Company 50-50 sometime in the 1920s.

In the late 1920s when Henry Shaw, and probably Melville Eastham too, saw that there would be bad times ahead, they felt, I think, that the tremendous boom in the financial markets in the 1920s would sooner or later meet its comeuppance, and they were right about that, too, when the great depression occurred after the crash of '29.

But Henry Shaw took half of his ownership and put it into a foundation which is now the GenRad Foundation. His purpose in creating that foundation was to be a "rich uncle" to employees who might have financial hardships which would impact their work. Today, the GenRad Foundation works entirely for causes outside the Company, because the IRS doesn't allow such a narrowly focused receiving audience as employees of just one company. The Company took those things over, and in addition there was new help from health insurance and social security. A lot of things occurred during the Roosevelt administration and thereafter that made the private "rich uncle" unnecessary, but it was way ahead of its time. I remember one employee told me that when his daughter had a very serious operation in the hospital, Mr. Shaw, who was a very quiet, true gentlemen, came down to see him at his workplace at the bench where he was assembling some products, and he said "I understand your daughter is to come home from the hospital today." He said, "Yes, Mr. Shaw, that's true. I have to leave soon to go and get her." Mr. Shaw said, "No, you don't have to leave. The Company nurse will go and bring her home if that is all right with you." So he said, "Okay." The next thing he said was, "And just send me all your bills and we'll pay them and no one will know the difference."

The Company has long had a reputation of being a very paternalistic company in the best sense of the word. That type of company can be bad as well as good like everything else. That was an era when people looked to stay with a company for life. There was nothing said about that and nothing written, but it just worked out that way at General Radio once people got in, they were glad to be there for the most part and stayed. If they liked the Company and the Company liked them, then you generally never thought of leaving. And that happened to me. I never thought of leaving.

Chance brought me to GenRad, like most important things seem to be governed by chance, according to the chaos theory these days. Our family was very poor financially, and I lived in the MIT Student House, which you had to be poor to get in. They charged $7.00 a week for room and board, which was about a third of what it cost to live any other way at MIT. It still exists, by the way, and it still is saving thousands of dollars for its members each year. I wanted to go into the cooperative course because of financial reasons. You alternated between a work term, getting paid at some company, and a school term, and that could help you get through college. I didn't want to move away from Boston, because I was living in the Student House and couldn't afford to live in a more expensive situation. Boston Edison was one of the companies but didn't interest me, because I wasn't interested in power. In those days, that seemed old-fashioned to me. Just a matter of personal interest. Electronics and radio were interesting to me. People said that there was this nice little company near MIT called General Radio. I never knew much about it. It was small, about a million dollars a year and about 150 employees, but people said it was a nice company to work for. So I interviewed them as a cooperative student candidate. I didn't interview any other companies. That was the way I got into MIT also, and in this case this was the only company I interviewed, and I got in. I said it was chance because they only wanted two people, and I was number four on their list of preferences. The chance and luck is that the first three ahead went somewhere else, so I got in, plus my best friend when they asked me if I had someone else I could suggest.

They were located near MIT by design. Mr. Eastham was very clever and very practical, but he respected greatly science and scientists and MIT in particular, and he wanted to be near it. He wanted to encourage interaction between the MIT technical people and his engineers. He was not only president but chief engineer. His office was really an engineering office. The presidency was kind of secondary. At that time one of our internal telephone extensions was the MIT operator and vice versa, so we didn't have to go through the outside operator to get MIT. He encouraged that over the years. General Radio was located on Mass Avenue across the street from the NECCO plant. It started on the third floor over a Greek restaurant right across the street and later on moved to 275 Mass Avenue, which is now an MIT museum.

The focus of the Company when I arrived was on instruments, precision electronic measuring instruments. It had a large product line by that time, hundreds of type numbers. The products ranged from simple little banana plugs, as they called them, (there are some in this recorder we are using or in the microphone we decided not to use) up to products that cost a few hundred dollars. The banana plug was one of Mr. Eastham's inventions. There were products such as impedance measuring bridges to measure resistance, capacitance and inductance in the laboratory, and most colleges had one of our 650A impedance bridges, designed by an engineer named R.F. Field, which is a most appropriate name for a radio engineer. General Radio introduced sound level meters for acoustical measurements and vibration meters for vibrational measurements as well as analyzers and stroboscopes that had been invented by Harold Edgerton at MIT and which General Radio made under license to Edgerton, Germeshausen and Grier who held the patents. So it was an interesting line of things, signal generators for testing radio receivers, volt meters for measuring voltage.

The export business was quite active in the early '20s. I had the privilege of meeting an almost retired administrative head of our Dutch agents in 1959, and he told me that he had personally handled General Radio's first export order, which was to Holland through his representative company, and that the product was a precision variable capacitor. In those days, they called them condensers, but now they call them capacitors. In the late 1920s, we were exporting to Japan and Russia and Australia and all the European countries, South American countries, and Canada. I think by the late '20s about a third of our business was going overseas, which was early for that. In 1959 we set up a central European contact point in Switzerland, which is kind of a neutral country and got along with everybody, and then we later bought our French representative and started manufacturing there and that's now our sales operation, likewise our Italian representative. In Germany we started from scratch rather than buying a representative. In England we started from scratch. Later in Japan in the 1970s we formed a joint venture in Japan to manufacture printed circuit board testers. That was done in concert with our Japanese representative, Tokyo Electron Limited.

The distinguishing mark of General Radio was the "black box." The original designs were wooden cabinets made of beautiful walnut or oak, lined with sheet metal copper to prevent electronic interference, and 1/4" aluminum panels with a proprietary, distinctive, black-crackle finish, with German-silver knobs and dials and white meters. We made interesting evolutionary changes there. We went through an enormous amount of work to go from black to dark charcoal gray. It cost hundreds of thousands of dollars to change tooling and specifications. We were so conservative that afterwards some customers didn't notice the difference. Then we went to lighter colors after that.

Management in general was quite conservative. Mr. Eastham had formed a lot of committees. Committees generally tend to be conservative, and they take a long time to deliberate. Strangely though, it was an innovative company in spite of that. The Company had an enormous number of firsts -- the first vacuum volt meter, the first sound and vibration meter, the first stroboscope and on and on, and somehow that came out of these committees. I think part of it was because of the way their engineering department was organized. Each engineer had his own private office with a door you could shut and a bench and a desk and a phone, anything you wanted plus a very capable experimental shop of machinists and assemblers that would do whatever an engineer wanted, no formalities. He would just go out and say please do this, and they would do it. It was a good relationship then. They were pretty much allowed to do whatever they wanted. If an engineer got an idea for a new kind of wave meter, he would just go ahead and do it, and after he was pretty sure it would work, he'd propose it to the development committee, and the development committee, after arguing about the color of the lines on the meter but never discussing any of the big things, as most committees do, would approve it, and then when it ran over its budget, they'd approve the extension, and generally after you'd spent three times as much as the original estimate, it would be finished. It would go into the catalogue and it would usually sell well for many years.

In 1941 as a coop student, I first spent the summer in the manufacturing department in seven different departments, the receiving room, the plating department, small parts assembly and so forth. In the second term in '42, I was in the calibration laboratory and calibrated a number of different kinds of instruments, which was quite interesting. The third term I was assigned to Don Sinclair, who was considered probably the most competent engineer at the time in the Company and who was working part time at Harvard's radio research laboratory. In those days although I didn't know it at the time, it was America's countermeasure laboratory. All the countermeasures in electronics were developed there. So he was kind of back and forth between Harvard and General Radio. I was assigned to him, and he and I worked on the design of a probe for a very- high-frequency vacuum-tube volt meter, which was kind of interesting. So I got to know him, and he eventually became president, and I eventually became his successor.

Don Sinclair was president from 1965 until 1972. He announced his intention to retire in March 1973, and three months prior to that he had arranged for me to be elected president and chief operating officer, while he retained the title of chairman and chief executive. That existed until he retired at the annual meeting time in 1974, and at that time I became president and chief executive, although we didn't use the CEO title in those days, just president. Then we dropped the chairman title at that time. We use the title chairman in an interim time when the former CEO is transitioning out, and one of my favorite sayings is "transitioning from who's who to who's he."

I remember hearing that there was a flap in town, I was pretty remote from it living in Harvard, but apparently Don was on the school committee and felt very strongly that the schools in West Concord and the schools in the main part of Concord should be thought of as one, that the West Concord schools should not be thought of as "the other side of the tracks," which apparently some people in Concord saw them as. He felt very strongly that the people in West Concord schools should not just be the people that live in West Concord, and that they should be integrated. I guess he won that battle, but I guess it was an unpleasant battle for him at times in the town. He lived in Concord before the Company moved out here in 1948.

I was a new stockholder in 1947, and under the Company's stock bonus plan, whereby the ownership of the Company was continuously transferred through stock bonuses each year from retiring employees to new employees, and I was attending my first stockholders' meeting. I remember having seen some maps of what is now the Concord land in the office of one of the engineers, who had been commissioned by Mr. Eastham to look around for land in the country. The way Mr. Eastham described it at my first stockholders meeting, he got up and said that the traffic was getting worse, that most of the employees don't want to live in the city, (which is an interesting juxtaposition with Sinclair's later feeling that people should move back to the city and not let them go to rack and ruin) and that commuting takes a toll. So he felt it made sense for the Company to move into the country, where there is fresh air, birds and trees, and not so much traffic, and good living at lower cost. It was an interesting meeting because the treasurer, who lived in Winchester and who did not believe in the country, and the president, who lived in Lexington and felt that was country enough for anybody, weren't in favor of any such move. But Mr. Eastham talked to the perhaps 150 employee stockholders at that time and did a selling job, and the president and the treasurer were obviously taken by surprise. The president didn't quite know what to do and said, "Well, perhaps we should have a show of hands and see what you people think about this." The whole room of hands went up. Somebody referred to it as "the magic of Eastham." Then the president, who was presiding, said "Well, are there any in opposition?" and two hands went up. One of them was Martin Gilman, who was in the advertising department, and he said he thought they should think about it longer, and the other one was Ivan Easton who came out with an interesting comment, "Well, I live in Teaneck, New Jersey." He was running the New York office, so he wasn't really serious. The president was Errol Locke, a very fine man who lived 100 years and just recently died, and the treasurer was Harold Richmond, who in the 1930s was the president of the Radio Manufacturers Association. Eastham was, by the way, treasurer of the Institute of Radio Engineers as long as anyone could remember, and Don Sinclair was president of that organization in the early '50s. That was the largest professional society in the United States.

We bought the land in Concord in 1948, the year my wife and I were married. The first building was Building One where we made the Variac(TM) continuously variable auto transformer used for controlling lighting, heating and industrial processes. That was completed in 1951. It was managed by two gentlemen who lived here in Harvard. Pete Cleveland managed the office functions and Charlie Rice managed the manufacturing functions. That went very well. Then in 1957 they did Building Two, and some engineering moved out at that time. Then in 1958 they finished Building Three, and everything else left Cambridge, and that building was sold to a company called Epsco Electronics. Later it was acquired by MIT for a museum. So as of 1958 we were completely in Concord. We had sales offices in about a half a dozen major cities in the United States.

I think I heard that Concord had set out to attract industry, and they set aside this land. We bought all of it, the whole 70 acres. It later turned out that a good significant part of it is a flood plain, and there have been two or three occasions where we've had water almost up to the first floor. Nowadays we probably wouldn't be allowed to build that close to a 500 hundred year flood plain.

I know I never asked for a raise, but that may come as much from my personality of the fear of being denied and not wanting to go through that, but I never felt I had to because they came through every six months like clockwork and were usually pretty generous. I found I was making a lot more than some of my classmates who were brighter than I was in school, and so I just never put that on my list of things to think about. It was automatic. I just went about my business and let the Company worry about what I got paid for it. In addition to that, there were cash bonuses twice a year, and there was a stock bonus once a year, and there was a profit sharing trust contribution once a year. These things were all staggered through the year, and usually the closing date before the determination was one date and then two or three months later was when the money was transferred. By the time you got the payment from the last one you were already two or three months into the next one and people used to joke about "there's no good time to leave."

The Company was advanced in providing health insurance. Back in the late 1920s there was the General Radio Foundation that Mr. Shaw started that gave private assistance, but then the Company was one of the first subscribers to Blue Cross/Blue Shield when that became available, and when their Master Medical Plan came out, which was the first big comprehensive plan, General Radio was the first Massachusetts company to sign up for it.

Back in the 1960s, Digital Equipment Corporation, under the direction of Ken Olsen, came out with what was called the PDP8, which was the first minicomputer. It took off, and our engineers were fascinated with it. The Company was free enough in what they allowed engineers to do. They allowed them to buy them and try them and see what they could do with them. Somebody got the idea of building a universal tester for our own products, so that we wouldn't have to develop or build a specialized tester each time we developed a new product. The idea was to use the general purpose computer to control some measuring instruments under the control of a software program that would be written for the particular thing to be tested, and you connect that thing to the tester with a special cable that would fit both of them. But when you had another product to be tested, all you would have to change would be the cable and the software program, the computer and the measuring equipment could stay the same. That's basically what a computer controlled board tester is. This became a catalogue product in 1969 when we had designed it for our own use, but I think that the group that was doing it had in mind that it ought to be offered to the public because it was the most fancy looking product we had ever built. It was $30,000, and at that time, the most expensive product we made was about $1,000. So it was really a change. We learned a lot in the process and are still the world's leading supplier of computer controlled printed circuit board testers, with our friends at Hewlett-Packard a close second. That product introduced in 1969 really took off in 1973, my first year as president, and that was sheer luck. I certainly didn't plan those things to happen that way. I was always an encourager and supporter of that program, but I didn't have much to do with it otherwise. By that time I guess encouragement was what was most needed from me because I controlled the budget, so they got what they needed to develop it and put in place a new sales force. It took off, and the Company expanded in my first year from $33 million sales to $45 million sales in one year. I attribute that to the work that had gone on before under Don Sinclair's leadership. He encouraged us for seven or eight years previously to "think systems." GenRad had to get into the systems business and to work with computers. He didn't know any more than I did what they were going to do, but he just knew somehow intuitively that that was the direction the Company had to go in, and he was absolutely right.

The peak was 1984, our business was expanding 35-40% a year, and we were up over $200 million sales annually. For 1984 we anticipated and budgeted another 40% growth, but it didn't happen. That was really the beginning of this period we're now suffering through, wherein a lot of electronics companies had to lay off people and shrink. We encountered it early. We were madly expanding and expanded too fast. We got up to 3400 people, and we couldn't keep up with the demand. Then all of a sudden, faster than you can let people go, especially if you care about them, business shrunk. I think the business is now down to about $160 million sales. It's still a respectable amount of business, and that shrinkage is less percentage-wise than many other companies in this area had to experience. Nevertheless it was a difficult time. I think there may be about 1200-1300 employees now worldwide, approximately half of them in Massachusetts and the other half in California and U.S. sales offices and the European sales offices.

The major product was, and is since 1970, the computer controlled printed circuit board tester, and that's been evolving through a whole bunch of successive models. We didn't know it at the time because you can never find out industry figures that are reliable until a couple of years after the year in question has passed. We now know that 1987, which just by coincidence was my last year, was the peak sales year for the printed circuit board testing industry worldwide. So GenRad, Hewlett-Packard, and all the other competitors sold more that year than any other year since, and it's been going down very steadily. Back in its heyday, quality was not very good by today's standards, even though it was about the best in the industry. It was considered acceptable because no one was doing better in electronic printed circuit boards, but when they were first assembled and soldered together, usually only 25-35% of them would work. So they had to be tested and fixed, and that was what our testers did. They tested these boards and told technicians who were not engineers, what component to change or which wires to fix. That was the norm of the industry. Then quality started to improve, and the Japanese taught us that our ideas about quality were wrong. Quality in fact can be almost perfected. For example, that IBM computer that I have over there, that I bought from the Company for $100 when I retired, I got in 1984 and it has never failed. I've used it for nine years and there have been no failures except when I do something wrong. So basically now the quality has been improved to the extent that companies do not need to do so much testing; they do it right the first time. Plus the fact that the electronic industry generally has been suffering from the recession, like a lot of other industries -- the combination has been severe. But the increase in quality and the reduced need for testing is not going to reverse, even though the business cycle will.

Jim Lyons is the current president, and he just succeeded Bob Anderson, who had succeeded me. I think the most important challenge ahead for GenRad, other than getting its costs in line with actual revenues currently, which I think Jim Lyons is trying to do very hard (and which is all that Wall Street cares about for the most part) is to decide on which markets the Company has strong capabilities in and give them more focus to find growing markets, and to abandon in a graceful and responsible way those market areas or product areas that do not have the growth potential, or are too competitive, or are obsolete.