Ian Gillespie

Gillespie & Co., Inc.

300 Baker Avenue

Interviewed July 28, 1999

Concord Oral History Program

Renee Garrelick, Interviewer.

I had a relationship with GenRad a long time ago. In 1986 we bought from GenRad the site that was scheduled to be their world headquarters, which was generally regarded as the finest site on Route 495 in Littleton. It did not have permits, but we subsequently got it permitted for 640,000 square feet, a $100 million project. I worked very closely with GenRad during that period of time and knew that ultimately this building (300 Baker Avenue) would become available. It was obvious that someday it would become available.

I had a relationship with GenRad a long time ago. In 1986 we bought from GenRad the site that was scheduled to be their world headquarters, which was generally regarded as the finest site on Route 495 in Littleton. It did not have permits, but we subsequently got it permitted for 640,000 square feet, a $100 million project. I worked very closely with GenRad during that period of time and knew that ultimately this building (300 Baker Avenue) would become available. It was obvious that someday it would become available.

In 1996 I was at a dinner sitting next to the broker who had been hired for this building. Unbeknownst to me, they had put it on the market and I hadn't realized that. I had asked my broker to stay in touch and he had lost touch. So I was sitting next to the broker for GenRad and I said, "Oh, I desperately want that building." He said, "Well, it's too late, it's under agreement." It was under agreement to a fellow that I knew very well, who was a competitor. I said, "Well, if it's under agreement to him, then I want the information tomorrow. I've got to have it immediately because I know he will not close on the deal." This was Don Chiofaro through the brokerage firm of C.W. Whittier. Sam Altruder was the broker. Very intelligent guy. I shouldn't put Don on the rack, but as soon as I heard it was Don, I said, "Sam, I've got to have this tomorrow. I know Don will hiccup on this deal." Sure enough, Don did hiccup on the deal, but then we lost it to Boston Properties. Then Boston Properties for whatever reasons fell out of bed with GenRad and it went to a firm called Brickstone Properties. Then for whatever reasons that fell out of bed.

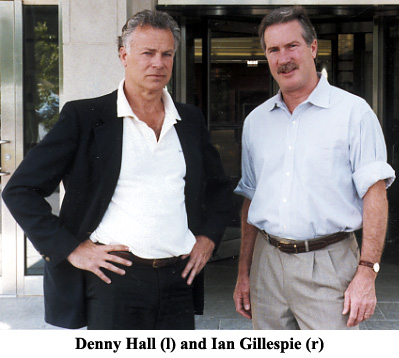

So I worked for about a year and everybody else was tired. GenRad kept changing their mind as to what they wanted and they kept changing the price. I considered the price irrelevant relatively speaking because the price initially was about $4 million and later was $6.5 million. Well, that sounds like a lot of money, but we were dealing with 400,000 square feet and 75 acres of land. At that level, if the property was $10 a foot or $15 a foot didn't matter given that it was going to be $60 a foot or something like that when we were finished. The purchase price was irrelevant, relatively speaking. So I kept pursuing it. I'd work until 11:00 at night redoing the numbers every time. Everybody else got frustrated and I just refused to be frustrated, I wanted it that badly. So we made a deal with GenRad, even though I said to them, "I've worked with you before. I bought the site in Littleton." And they said, "Well, nobody of substance here now was around then, so it's a whole new ballgame. We don't know you from Adam." But at any rate, we got the property. We being three partners, John Hall, Dennison Hall and myself.

It was my task to get financing. I went out to 60 firms and ultimately we wound up with three very interested parties which was my goal, and narrowed it down to one which was Lehman Brothers. It was their own money. It was the partners fund at Lehman Brothers -- very smart, very aggressive, very wealthy and very knowledgeable. They were fabulous. They wanted the deal badly and we wanted them badly. It was a match made in heaven. So we got together with them and bought the property, committed $17 million or $18 million at a minimum to rehab. We took the building back to the skin and rebuilt it with the exception of the mechanical systems. The electrical system and the heating/ventilating/air conditioning systems were fabulous. We didn't need to do very much to those. We needed to reduct them, but the basic systems were great.

We bought the building and closed in December 1996, and GenRad was due to stay on for another six months which they did. The biggest deal point we had with GenRad was how long they would stay because we didn't want them to stay more than some logical period of time. We wanted to get at the rehab of the building. We narrowed it down after a back and forth on that point, and they stayed for six months. We had worked on this for a year. Our first offer to GenRad was in October 1995 to give you some sense of time.

During the period we were under agreement but not yet closed, we started discussions with Lucent Technologies. They had acquired a small firm out in Boxborough named Agile Networks, and Agile and Lucent were desperate for space and actually moved into temporary space in the building. GenRad was kind enough to vacate one wing for us entirely. They were already not using most of it. We set up some security systems and we had Lucent occupy some very raw space. Then they took yet another floor in the same wing so they ultimately had about 22,000 feet of temporary space. When GenRad left in the summer of 1997 we started the rehab and we worked around Lucent which was terribly difficult, and then in January 1998 moved Lucent into completely renovated space of about 90,000 square feet.

We saw several things in this site that the market considered negatives that we thought were positives. The ultimate question was Concord itself as a location between Routes 128 and 495, and actually also between the Mass Pike and Route 93. It is very central to that market. There were some who said it is neither 128 nor 495, and it is therefore disadvantaged by its location. We said Concord is a historic crossroads. It's a hub of a road network that goes back in history for 200 years, and we are central to the high technology companies that populate 495 and 128. And that has proven to be the case actually.

The second thing was the architectural design of the building with fingers is quite odd by modern standards. Everybody said that it is a terrible layout, but we said that's a tremendous amount of window line to interior space. That works extremely well for the modern layout of cubicles where everybody has, as the architects have an expression, an experience of the outside. So there was an experience of the outside for everybody. That we felt was not a disadvantage but an advantage, that we could work with the layout of the building and make it adaptable. It was particularly adaptable to the modern technology firms, and that has proven to be so. It also works well for offices if they wanted them. Finally the building had huge infrastructure. Infrastructure that nobody in their right mind would build today. The building itself is a poured-in-place concrete building as opposed to a steel frame building. Very unusual. It has a very large capacity for HVAC and a very large capacity in power. So we thought those elements would appeal again to the emerging technology firms, and in fact that happened as well as the location.

We thought we saw the potential. Of course, it was a big gamble. We were certainly putting ourselves on the line to see if what we thought we could do could be done.

There was no real tie-in to what we did in Littleton and what we did here. Littleton was new construction and it was more campus. We knew the market very well as a result of our work in Littleton. We actually thought this building would draw, and in fact has drawn, more from the east than it has from the west. It happened that Lucent came in from Boxborough because of Agile. And Lucent has grown by acquisition of other firms particularly Prominent and more recently Ascend. And in turn Ascend had recently acquired Cascade and Stratus, two major firms on 495. They have an opportunity to bring some of those people here because again it is very central. But most of our other firms have come either from across the street or from 128 and Cambridge. So there's been a migration west. We thought that would happen and we thought we could provide a very high quality, cost effective space that would be advantaged by comparison to a Waltham and Burlington.

The building is now 408,000 square feet. We added a 15,000 square foot mezzanine where there had been a warehouse. We needed to make the space that is now the cafeteria actually smaller. It was too big of a space for a cafeteria. So we had an idea of adding a mezzanine and adding some office space which actually greatly improved the circulation through the wings that were overlooking the cafeteria. It's worked out very well. When I say add, we actually replaced some of the space they had.

We do have the best contractor in the business. John Moriarity & Associates we feel is an outstanding firm. The architects were a firm by the name of Tsoi/Kobus & Associates in Cambridge. Moriarity is located in Winchester. Our instinct has always been to go with the best people we can get, and that's what we tried to do. Most of the people who worked on this project had worked together before. I go back with Tsoi/Kobus since their inception 15 years ago. We also go back with Moriarity to his inception which was 18 years ago. They have worked with each other extensively over the course of the years. So it's a small business in many ways and we all know each other. It's a very collegial group. Actually our lead architect is a woman, Carol Chiles, so we had many talented women involved in this project as well.

One of the challenges we had to overcome was that the building was ugly. There was no way to get around it. Also GenRad had been in a period of decline for several years, for probably a solid 10 years, and had not been able to spend a lot of money on the physical plant, so it was just ugly. It was also extremely dated. It was all 1950s in its style.

When I bought the site from GenRad out on 495, Anderson Nichols was very hot after me to hire them as the architect. Anderson Nichols had done some of the additions to this building. They were very kind to me during the course of due diligence and very helpful because they had done all the work for GenRad and done all the work here. They said, "Ian, you've got to use us. We're coming off a lot of experience, we just finished the Wang Towers," which in my estimation were the ugliest buildings ever built in suburban Boston. We laughed at the positive, and the negative, that this was a building built by engineers for engineers. Architectural design had not been an issue. They didn't care. They didn't focus on that. So we had to bring the architectural piece of the puzzle to the table. Tsoi/Kobus did a fabulous job of doing that. That said, we then capitalized in a positive way on the fact that it was a building built by engineers for engineers and of course, our most important clients today are very high tech engineers. They love it. So we have the best of both worlds. We have some architectural flair while being a very strong building from an engineering standpoint. It was built extremely well. It was overbuilt at every turn, but it was built ugly.

Our understanding is that the building was started somewhere around 1950-1951 when they probably completed the first wing. It was built in a series of T sections. The first one being nearest the pond and the original entry was off Main Street. They built a phase every two years and they were consistent. They did a phase in ‘50-52, ‘54-56, '58 and '60. Then they came back in 1979 and 1980 and filled in the various T sections that they had created. It is a very odd situation. In the first building there were three stories on one wing and two stories on another, and we had no indication of why that was done. We just don't have any clue as to why it was done that way. Then they built a wing and then another wing and another wing, a T and across the final stroke. In 1979-1980 they came back and filled in this courtyard with three stories of office. They filled in this courtyard on the first floor and then on the second and third floors built a chiller plant, and in this one they put a roof over it and a curtain wall on it and that was a warehouse. Then we came along and left this one and left this one and we filled this in. We put a mezzanine in here so that these wings would flow around and put the cafeteria in here. That evolved after we had done our initial planning, we decided to do that. That didn't show up until we were deep into the architectural work.

We needed to accentuate the entry and we needed to create access to a courtyard with a central spine from an architectural point of view. We asked if the architects might create what we called the Ritz entrance. We didn't want to spend a fortune on it but we wanted to create a canopy of some kind so that in the New England winter people could get out of their cars when being dropped off out of the weather. But also it would establish visually and architecturally an entrance point. People recognize canopies as the front doors, an old trick. So we created a canopy and brought the road up to the building and created an oval entrance. The road at that point was actually quite a ways from the building. Then we redirected the road on the diagonal so it would come directly to the front door. In the old days it took you directly to the front of a metal clad single-story building and you had no idea where you were within the larger complex. There was no indication of entry. In fact I was standing with the architects outside one day and a van was going back and forth. It finally stopped and the fellow said, "Do you guys know where the hell the entrance to this building is?" We laughed and said, "Yes, we do." Then we turned to each other and said that's what we need to do, tell them where the front door is. Then we spent quite a lot of money on the front door. It is a little noticed thing. GenRad had a clumsy aluminum front door. We actually installed a very expensive front door much to the distress of the design consultant to our financial partners at Lehman who wanted us to go cheap. We insisted that we would have a fabulous entrance and presentation, and we do. We spent a lot of money to have a stainless steel revolving door with stainless steel side doors.

The revolving door had a very large practical benefit to it. Modern buildings are somewhat pressurized, slightly pressurized. It is how they function. They push the old air up into the ceiling and it is called a return air plenum, and the supply air forces the old air, the return air, back up through the ducts, so they are slightly pressurized. They have problems with single entry doors because number one it lets all the air out, but it also creates a cold draft very quickly. The revolving door has practical aspects to it. You have to have the side doors for handicapped access. In addition to that we were great believers of having a really elegant front door makes a difference to the way people tend to walk into the front door, look at the lobby and say boy, this is fabulous. But psychologically they were set up for fabulous as they were going through the door. We particularly like them to have to expend a little bit of effort to push a slightly heavy door because there is a feeling of you really entered a space and you actually have to work a little bit. So as peculiar as that may sound, we wanted a really fabulous entry.

The architects did a great job of using light. Throughout the tenant spaces, particularly Lucent and throughout our common areas, particularly the lobby, I think they exhibited an elegant eye for the use of light in very different ways. They have colored lights in some places, they have very bright lights in others, and they have skylights in some places. The curtain wall is designed very carefully for certain amounts of light but not too much light.

A curtain wall is simply an exterior wall that doesn't have a load bearing function. We created a new entry lobby through what had been a courtyard for GenRad. In those days you came to a receptionist and then walked sort of horizontally down the side and then down back to the spine of the building. You didn‘t go directly to the spine of the building. We found that was untenable for a multi-tenant building. So we created a new lobby and a new spine and it has non-load bearing glass walls on both sides which are also decorative. The amount of glass, the frame of the glass, where you do have glass and where you have a solid wall, the mix of glass becomes very important for what the experience of the passageway is to the person passing through. We wanted a sense of gardens. There are gardens on either side. We created those gardens but the entry experience is one of being, albeit protected from the weather, walking through a garden to the extent that we actually put out birdhouses and bird feeders and elegant garden furniture to accentuate that. A very relaxed experience and I hope a somewhat welcoming experience.

In certain areas you have a sense of tranquility in somewhat dim light. In Lucent space there is one area where they put very cool blue light around the ceiling perimeter that gives it an extraordinary high tech look. It's just a tube of blue light, but it is an area where they bring their clients to look at their technology and it is an area that is very cool, very, very high tech. They use a window framing system but in that case they were effective in making it a high tech feel as opposed to the lobby where we had a somewhat similar system, but it gave it a very elegant low tech feel. We wanted to create these various spaces and emotions. Buildings are sociological. They are not architectural, at least in our view. Buildings work when people understand the sociology, how people feel, and how they work with other people and interact with other people. For instance there is nothing more deadly for a woman shopper than structured parking. There is a feeling of uncertainty and shadow and a lack of safety, so you'll notice typically in the US you don't have structured parking for shopping. It is an unwelcoming experience for women. So we look very hard at sociology and how people will feel. Our courtyards are useless nine months out of the year, but the fact that they are there makes people feel comforted that they can have that if the weather cooperates.

The fronts of the building were modernized. The curtain wall of old brick we took apart and put it back together in such a way that the architects did a very good job of giving it a modern feel. They increased the size of the window, they used spandrel glass which is glass that is colored glass, and in our case it is Hartford green glass. It becomes an adjunct to the precast and the brick and the real glass, or so called "vision" glass. By opening up those curtain walls a little bit it gave them a more modern feel. It subdued the sort of 1950s schoolhouse effect that the building had. In the lobby entrance it's a matter of a very elegant expanse of glass and hard wall. Then in the cafeteria, which is where we spent a long time on the curtain wall, again it is a very elegant design which creates not only the light of the cafeteria, but is the light for the tens of thousands of square feet of office space that are overlooking the cafeteria, that use the cafeteria curtain wall for their access to exterior light. When we bought the building, GenRad had blocked up the windows that were overlooking their warehouse. When we made that a cafeteria, we knocked those blocks out and put glass just the same as the exterior glass back in so that those people overlooked the cafeteria. Also by creating light in the curtain wall of the cafeteria we gave them an opportunity to look outside, they in effect look through two windows, their own window and the cafeteria window. We worked hard on not having too much light in the cafeteria but having enough so that it would give all those people a sense of looking outside.

We knew we had to have a cafeteria. We have the luxury of having a large building. We have a large enough population to have a cafeteria and to have a fitness facility and a vending machine area and so forth. My favorite part of the cafeteria is that we originally designed it with a series of what are called in the trade four tops, tables for four people, and a few round tables that would accommodate six people. As the tenants came in, they would pull the square tables together. They kept pulling them together and we kept pulling them apart at night. And finally we gave up and said, "Wait a second. This is a manager's dream." These people of their own volition are pulling these tables together to sit together at lunch and talk to each other. That's a manager's dream. We have a community here. We kept trying to break up the community but that was the wrong thing to do, so we now leave it. We do put flowers on all the tables but we leave them together. The tenants are thrilled.

Ultimately the building will have about 1500 to 1600 people in it. Today we are 98% leased, but we are not yet more than about 60% occupied. The tenants are moving into their expansion spaces now. So we are not yet at maximum population but we're moving in that direction. We're probably at about 1000 today. Probably by the end of ‘99 we'll be at full population.

Chris Whelan has seen this and we have not been to the planning board yet. Those are the two proposed sites. We have a 75-acre site all told -- a large site. I believe we might be the largest commercial site in Concord. Certainly to my knowledge the largest single building. So we see piggybacking on our existing driveway, the existing road system which is in pretty good shape and building two buildings to appeal to the same kinds of tenancy we have today as well as one other adjunct potential tenancy which is the medical community. It is very logical that this is the place the medical community would like to be. It's again a crossroads.

One building would be up by Baker Ave. on a high part of the site, and this one is between us and Route 2 in the woods. It would be a lovely wooded setting with a pond and a river. It is an exquisite site. It's as handsome a site as Concord has.

We probably won't be able to build the new buildings to the high standards of the building that we inherited in terms of the infrastructure. From a design point of view, yes we will take it to the highest level. They will be as good as anything you can find in the suburbs. Good design is not necessarily expensive. In fact we regularly joke that you get a very expensive architect to get a good building, but the building doesn't have to be expensive. Each building will be about 100,000 square feet each. We don't know if one will be specifically for the medical community. We are followers not leaders when it comes to the tenancy. The tenants tell us what they want. The medical community today is in deep distress. Major Boston hospitals are losing money hand over fist with the prices today in the medical community, so for the moment they're actually a little startled at the losses they've had and trying to understand what their role is and will be. We have had some interest from the medical community and would be surprised if in the future we didn't have some interest from them. We obviously are very comfortable in the high technology community and that would be our first market.

Our existing tenants include Lucent Technology and Solidworks, headquartered across the street, founded and run by a wonderful character by the name of John Hirschtick, who made his first million playing blackjack when he was at MIT. He started in his garage in 1994. They do software for mechanical engineering on a personal computer. Excellent firm. They used to come over when we were in renovation and we would talk about space and I'd say "Well, I'm not sure, you don't have much credit." And he'd say, "Well, I'm not sure, you don't have much of a building either." So we had this back and forth. John was acquired for $300 million by the wonderful French firm, Dassault Systemes, S.A., the largest CAD firm in the world. All of a sudden they needed a lot of space and they had fantastic credit and they also discovered they liked very much what we were doing with the building. So we had a very good personal and professional rapport, and they are now our second largest tenant. Netsuite is a wonderful firm co-owned by Fidelity Capital and Cisco Systems. They were one of our early tenants. They have about 22,000 square feet. Basically I think they're software, but they do some hardware. We have Earth Tech, who are civil and environmental engineers. They are a subsidiary of a wonderful firm called Tyco Industries, a huge firm. They have about 22,000 square feet. We have OneSource moving out of Cambridge. They just went public two weeks ago. They provide very in-depth information on corporate America and they provide it through a website by subscription. A small entrepreneurial arm of Mitsubishi is due to move in in another month with 15,000 square feet. We have Manufacturers Services. They would buy a factory from Digital and continue to do the manufacturing for Digital, but also do manufacturing for others so they maximized the capacity. They have plants all over the world, and this is their headquarters. They have about 15,000 feet. We have Internet Business Advantages, a small firm out of Burlington working with companies to maximize their Internet technology.

It's wonderful for the adjacent community of West Concord as well. The barbershop has seen more activity as has the sandwich shop, and the gas station, and so forth. GenRad in its later years only had about a quarter of the building occupied. They would say half but it was what I consider a quarter. So the surrounding community of service industries had lost that base of customers. We have some very wealthy people in the building. And just the regular old engineers make more money than they know what to do with. What they care about most is playing volleyball and we have volleyball nets. They jog and they have basketball nets and street hockey nets set up in the parking lot. They're a very athletic community. We knew we had to build a fitness facility because that's what everybody says. But you usually only get a hard core of about 20 people using such a facility. So we have it and those 20 people are having a great time because they generally have it all to themselves. More people obviously use it in winter than in summer.

The demographic of the tenancy is very multi-cultural which I love. The high technology is a total meritocracy and I love it for that. That part of it is really great. It doesn't matter how young you are or how old you are. It doesn't matter the color of your skin or the nature of your religion, and we have every religion and every race in the building. This is to the extent that I asked everybody's opinion if it was okay to put up Christmas lights at Christmas. Everybody said that was generic enough so that nobody would be offended. But I checked to make sure our Muslim tenants and our other tenants would not be offended. So we try to be sensitive to that. The tenants are relatively affluent, very well educated and again the multi-culturism makes for an atmosphere here. What people are concerned with is somebody's skill.

The GenRad legacy we have here is a proud legacy. They were General Radio. They were very much involved with technology that provided the defense of the country in World War II, for instance. There were very noble in their pursuit of technology. Technology is a holy grail more than money is a holy grail, which is somewhat interesting and I think there is that legacy today here. The work that these firms are doing is the highest of the high tech in the world. The work that Lucent is doing here is related to what is known as convergence. The convergence of voice, data and video and the switching that's required when you put those three different data strands together, that's the work Lucent is doing here and it's world reknowned. It's happening right under our roof. For a non-technologist, I get to play host to a party of very talented people.