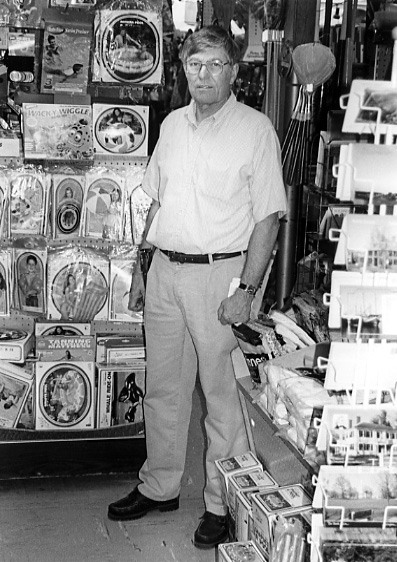

Maynard Forbes

25th Anniversary Perspective of the end of the Vietnam War

Age 63

Interviewed November 28, 2000

Concord Oral History Program

Renee Garrelick, Interviewer.

Click here for audio in .mp3 format

Maynard Forbes entered the military as a career and served 27 years before coming home to run the family business. His family came to Concord in 1951 when his father acquired the West Concord 5 & 10.

I graduated from college in 1958, got commissioned and went into the service in December 1958 at Fort Devens. I was already in the service for ten years before the Vietnam War heated up. In the early 1960s during the administration of President John F. Kennedy the support for the war was strictly on an advisory basis. It was advisors and special forces units that went into Vietnam to work with the local military people. They were all over Southeast Asia, in Laos and Cambodia at the same time, but primarily Vietnam. There wasn't a lot of publicity about it in this country. In the early ‘60s I was in Germany and looking for volunteers to go as advisors and the like to Vietnam.

I graduated from college in 1958, got commissioned and went into the service in December 1958 at Fort Devens. I was already in the service for ten years before the Vietnam War heated up. In the early 1960s during the administration of President John F. Kennedy the support for the war was strictly on an advisory basis. It was advisors and special forces units that went into Vietnam to work with the local military people. They were all over Southeast Asia, in Laos and Cambodia at the same time, but primarily Vietnam. There wasn't a lot of publicity about it in this country. In the early ‘60s I was in Germany and looking for volunteers to go as advisors and the like to Vietnam.

At that time it was containment for fear of communism spreading. I think the idea of the advisors was to make a stronger military force within the country and to hopefully ward off any of the theoretical spread of communism in Southeast Asia. In 1965 we put actual American units in. The first unit in was the 173rd Airborne Brigade. From there the number of troops and the acknowledged presence of troops started to build.

The whole domino effect and that Vietnam was very crucial was being used as the reason for being there. If you allow the party line thought from our side as opposed to the communism side, that was what was being pushed -- that if the countries down there went, then soon it would be into Indonesia and off into Thailand and across India. They were looking to stopping it there and trying to make sure it didn't spread.

The first time I went to Vietnam in June 1968 as a major my specialty was field artillery. I was given the task of developing a tactical operation center, the artillery side of a tactical operation center, around the Bien Hoa Airbase in the City of Bien Hoa which was east of Saigon. Saigon had developed a center similar to this just shortly after the Tet Offensive. My responsibility was to establish a set of towers where personnel in the evening hours would use scopes to spot rocket flashes or mortar flashes. We had a radio network that we were able to call in artillery fire from a number of different units around the Bien Hoa area, and we were in touch with the gunfire helicopters so we could call on them if there was a need for it. We also had the requirement for clearing artillery fires. All the artillery fire that was conducted within the area had to be cleared through us to make sure that it was going into an area that was not built up area or an area where there were friendly forces. That was about a six-month assignment.

By 1968 there were probably about 550,000 soldiers throughout Vietnam. The majority of them at that time were in American division and brigade-sized units plus all of the support forces that went to making these units able to exist. In other words, the big Cam Ranh Bay facility, Long Bien covered acres and acres of land that was all support people which included hospitals and supply areas. So I think that was the figure that was generally accepted.

On that tour I did not interact much with the Vietnamese people. The advisory people on the ground, and there were still a lot and their numbers were increasing, were the ones that dealt directly with the Vietnamese people. My task was to deal with American units and coordinate the movement of artillery units. After the job as the head of the tactical operation center, I became the operations officer for the field artillery group which had four artillery battalions. They were scattered over the eastern half of the three corp area which included the Bien Hoa base, all of Saigon and up into the corner near Cambodia.

The Viet Cong were industrious and ingenious, and that observation came about in my second tour when I wasn't an advisor. My experience directly with them was after the cease fire in 1973. If the question was about what we knew of them while we were in American units, yes they made use of every little thing, such as watches to set off the rockets. They'd be ten miles away by the time the rockets went off in the evening. They were set by a watch that was powered by batteries that some GI probably threw away. From that standpoint you could say they were industrious and ingenious, but to live in caves and tunnels and the rest for long periods of time, they had to be somewhat industrious.

Our country was very divided in 1968 in regard to the war. I'd read the articles and listened to whatever was going on and I think at that point I was a military officer with the thinking that the side that was putting the people into Vietnam was probably somewhat correct. That was the job I was given and within reason that was what I ought to be doing. Not to follow it right straight down into the ground, but there were directives addressed that were followed to conduct a mission.

At that time I had a family with four children. Understanding that nobody wants to go over and stick his head in front of a rifle bullet or a hand grenade or whatever, I obviously tried to follow safe and secure procedures. But, there were often times where you had to conduct whatever business you had to do. Yes, I thought about the family, I thought about all of it, but some things have to be done. This was the kind of war that you didn't always know who your enemy was. In the first tour, while I was dealing with American units, I probably didn't have the exposure out in the countryside. When I would go from base camp to outlying units, it was normally by air. Yes, there was some danger of getting shot down, but not near as much as in the second tour, floating up and down canals in a little two or three-man sampan or biking across rice paddies not knowing who was behind the bushes or the scrub up in front. That timeframe was 1972-'73. There were nowhere near as many American forces in the country. There had been peace talks or attempts at peace talks in Paris for a great long time, so it probably wasn't quite as dangerous a situation, but there were still lots of mines, lots of bungie pits and the rest.

A bungie pit is a hole dug in the ground that has sharpened bamboo stakes run in the bottom of it and then it's covered with leaves and brush to make it appear like it's solid ground. When the person walks along, he steps through and rams the sharpened bamboo up into his foot and it probably had all kinds of stuff they could device on the bamboo stakes that cause infection, etc. There were land mines. They captured American land mines, they captured grenades, they captured all kinds of munitions and would booby trap them and use them wherever they could.

In the second tour in 1972 I learned the language and the customs of the people. I went to a combined State Department and Defense Department school, got an appreciation of the language so I could go down in the marketplace and talk with the Vietnamese that I was dealing with. In a slow conversation I could get the idea of what was going on. I lived right out in the village. I was about 40 miles away from my next headquarters. There were three of us. I was the senior person. I had a captain and a sergeant who worked for me. We had a variety of duties dealing with the people at the district headquarters which was where we were located. We helped them coordinate things if they needed military assistance or helicopter assistance. We went along on their military activities to be sure that (a) they were conducting them and (b) if they needed extra assistance. We always had a radio and we could switch frequencies to call on assistance. This was down in the Mekong Delta. The province headquarters was in the city of Soc Trang which was south of Can Thu. The village I was in was Ang Wah and that was southwest of the province headquarters. It was a little tiny village at the intersection of the Grand Canal and several side canals, and it was an industrious little village. There was fishing, and outside there was rice grown, and there was a big Buddhist temple out to the west of us that we visited periodically just to see what interaction they seemed to be having with the other side. I'm not sure we learned an awful lot, but it was a very interesting place to visit.

I was providing information back through U.S. channels as to what was going on, how they were conducting their operations, what they needed, if things were in difficulty. There was an aid advisor who was at the province headquarters who periodically came out and dealt on the civilian side of it for aid assistance to certain parts of the village. The primary means of transportation was either walking on the small trails that led down along the canals or on a sampan which was a little, low, long, narrow canoe-type vehicle with a motor on it. For the most part their motors were with a long drive shaft because the canals were shallow.

At that point in order to get anything done it cost you a fixed fee plus a hidden fee. Graft was rampant. It was an inefficient government. Lots of things got siphoned off here and there. One of the best examples was concrete. The infrastructure people came to build or rebuild a reinforced spot for the two 105 Howitzers that were in the district village headquarters. They poured their concrete and went away and we were very happy only to find out they had only used about 1/3 of the concrete that was necessary, it was mostly sand. The first time they fired the guns, the parapet crumbled, so somebody was using concrete for some other purpose.

The cease fire was the last part of January 1973 signed in Paris. At that point there were very few American units and they all left during the period of time of the end of January to the end of March. What were left as far as American forces were some of the advisors who were divided up into military regions which were a little different than the divisions we had used militarily. The idea was that there would be peace talks at all levels, at the village level, at the district level, at the province level and at the country level. What our task was during this two month period was to establish meeting areas where these conferences or peace talks could take place. We worked to get schools and public buildings set aside and the appropriate tables, and in the case of district headquarters and province headquarters, microphones. The only actual talking that was done in country was in Saigon and that happened late in March. I'm not sure there was an awful lot of concrete agreement between the four parties at that time. The four parties being the Viet Cong, the North Vietnamese, the Vietnamese, and the U.S. Each of these four groups were to be represented equally at the table. Most of the discussion was on the size of the table, the shape of the table, the number of people who could sit directly at the table, and the number of people who could sit behind the people who were sitting directly at the table. I was not part of the discussion. My job was in establishing the areas, helping people find the buildings and the material that it took to put together the rooms in which all of this was taking place. We worked out of an operations center in Can Thu and for the most part flew to different locations in the Delta. On the 31st of March, everybody left the country. Everybody except a very small nucleus was left in Saigon, and those people left on the skids of helicopters in April of ‘75. During this two-month period the repatriation of the prisoners-of war took place. There were several plane loads that came into Saigon. Senator John McCain was one of the people in this group that came back at that time. He was in Hanoi and came back to Saigon and then off to the hospital.

The daily communications are what provided the country with the information to fuel the division. There were hawks and doves if you will, and depending on which side you happened to be on, you could pick or glean out of the 6:00 news anything you wanted to glean. I'm sure that some of the reports were slanted to make everything look a little bit better in some cases than maybe it was. That has come out in literature over the course of the last 25 years. Former Defense Secretary Robert McNamara's book and the rest would seem to lead you to understand that the body counts and the rest were sometimes a little bit fictitious. I think if you took the view from the reports as you went along until we came to the Tet Offensive in ‘68, we seemed to be doing very well. That was a slap in the face and it was a pretty rough time. The swing of the pendulum came back during ‘68 and ‘69 as we had the major build up of forces. I think we got sidetracked with Mei Lai and several other incidents and probably it's a wonder there weren't more.

The Tet Offensive came from North Vietnam. It was countrywide but primarily up north. But there was also a big push in Saigon. There were stronger pushes up north than in Saigon, but they were grinning for bear at that particular time. The North Vietnamese became a vanishing presence throughout the country. They were here, they were there and they supported the local Viet Cong during that time also. It was just a major push.

The rules of engagement were such that U.S. units were constrained to an extent from using the weapons that may have provided a tactical advantage. The strategic advantage of not knowing who you were fighting, finding units who were camped on top of great cave and tunnel encampments of North Vietnamese which today is the poorest area in Vietnam. Not knowing who you were dealing with was probably the biggest problem.

In the southern part of the country it's a hot dry season. You've got some terrain differences that are not apparent in the southern part of the country. The French found that at Dien Bien Phu back in ‘54 up in North Vietnam. They were in valleys and being annihilated because they were using unsound tactics. We had similar problems in the highlands where terrain was a deciding factor. In the delta it was a matter of being a wide open country. You could see for miles. You get into built up areas along the edges of the canals and there was opportunity for all kinds of guerrilla warfare.

My time was spent in what was considered the three core and four core area of Vietnam and that was all south of a line going east and west through Saigon, my area was all 30 miles south of that. I left at the end of March 1973.

The Democratic convention in 1968 caused a great stir. My experience with the ‘68 convention is strictly out of the military newspaper in Vietnam. I was in Vietnam at the time of the convention. I've listened to the reports and looked at the film clips and the rest since then. It obviously was kind of a reaction to what was going on over there shown strongest by the forces on the peace side of it who wanted us to get out. There was some made of it in the military newspapers in Vietnam but at the time it was not as well publicized there as it was here.

At that point by 1972 I had about 14 years in the service. I had reasonable marks for my performance and felt that I was going to continue on. I knew at that point that I was probably going to come back to Concord and become involved in the business where I am now, but there was enough going on in the business to maintain it for a period of time. So, I was going to stay and did stay. I came back from Vietnam in 1973 and my military career ended in 1982. I went from Vietnam to Washington for three years, Korea for a year, and then back to Massachusetts.

Being in the military I didn't feel left out like the veterans returning felt left out. I think there is now, was then, enough camaraderie within the military to deal with discussions of the war and activities in the war and the like. Coming back to the civilian community you came back to a divided community, some who felt you were right, some who felt you were wrong, and probably it didn't take too long a time to figure out who was who and neither one of them was going to pat you on the back for your time over there. Probably the advent of the wall down in D.C. is something that has helped. There have been things in the last few years that have made some of the Vietnam veterans feel a little bit more accepted. I have to say that here in Concord there is a group of the younger Vietnam vets who are now very prominent in Memorial Day parades, and I think they are the nucleus that will carry this activity on in the years to come. They are a good group. They are not spit and polish with one exception, and that one exception is Joe Venti who is "Mr. Spit & Polish" as a marine corps reserve and is very good at everything he does. Others include Jack Martinson, Gordon Robinson is out of town but still comes to participate