Concord Prison Outreach Program

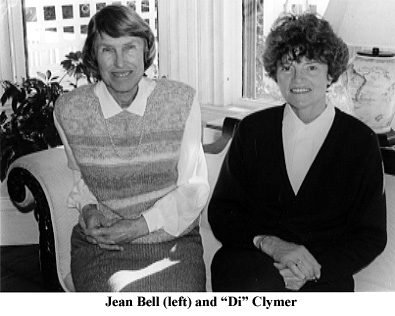

Jean Bell

1657 Monument Street

Year of birth - 1927

Diana Clymer

235 Main Street

Year of birth - 1943

Interviewed January 27, 1999

Concord Oral History Program

Renee Garrelick, Interviewer.

Click here for audio in .mp3 format.

When the Commonwealth decided to close Charlestown prison because of its poor condition, the Massachusetts legislature in 1873 voted one million dollars for a new prison. 1873 was a difficult economic time and Concord land was less expensive than that of Boston. The Cooke farm was acquired and 300 men hired to construct the new prison. Charlestown wanted their prison back because of the employment and in 1884 all but 100 of the 650 inmates were returned. Concord became the men's reformatory and a showcase for visitors. By the turn of the 20th century, more than 100 inmates were confined there, with the focus on learning a trade to reenter society from many vocational offerings and industries operated within the prison. The Waring Hat factory in West Concord employed women to decorate hats made at the prison. The reformatory provided local employment and contributed to the growth of the town.

Since prisoners could only be transported by rail, this encouraged the expansion of the railroad in Concord, with a railroad station, hotel, and restaurant across from the prison at reformatory circle.

Diana — I have felt lucky to be doing this work and very connected with Concord and its history. Concord is a very unique community with a great deal of energy and very caring. Those aspects have shown themselves even in our prisons. Concord petitioned the legislature in the late 1800s and asked to have a prison built here. I think that is quite an unusual situation to have done that. The townspeople did that for two reasons. One was an economic reason to bring employment to the town. All the people who worked in the prison lived in Concord so it provided a great number of jobs. But, they also did it because they wanted to separate the youthful offenders from the older offenders who were in the Charles Street prison in Boston. So it started in the late 1800s and it was called the Concord Reformatory. People in town were working in the prison and people in town were volunteering in the prison. There are wonderful stories from different people in our community now who can remember times that they were volunteering in the institution with their parents. So it really has been a tradition of involvement, of local involvement, in the prison.

Diana — I have felt lucky to be doing this work and very connected with Concord and its history. Concord is a very unique community with a great deal of energy and very caring. Those aspects have shown themselves even in our prisons. Concord petitioned the legislature in the late 1800s and asked to have a prison built here. I think that is quite an unusual situation to have done that. The townspeople did that for two reasons. One was an economic reason to bring employment to the town. All the people who worked in the prison lived in Concord so it provided a great number of jobs. But, they also did it because they wanted to separate the youthful offenders from the older offenders who were in the Charles Street prison in Boston. So it started in the late 1800s and it was called the Concord Reformatory. People in town were working in the prison and people in town were volunteering in the prison. There are wonderful stories from different people in our community now who can remember times that they were volunteering in the institution with their parents. So it really has been a tradition of involvement, of local involvement, in the prison.

I got involved in the ‘60s shortly after we moved to Concord. I became active in the First Parish Church and joined the social responsibility committee. The committee asked each one of us to dream up our own project and execute it. I was brand new to the community and I looked around and saw this prison and I was curious. I had a young child and I didn't really want to go into Boston to do my community service and was curious as to what would be doable here. So I set up an appointment with Nick Genakis who was then the superintendent of the institution. I went in and asked him what a group of people could do in the community for the prison. Bless his heart, he didn't laugh. He said, "We could use some curtains for the infirmary." I did not know how to sew so it struck a panic in my gut, but I smiled and said, "That would be wonderful, we would be happy to do that for you." I immediately found some seamstresses and we went to work and we made curtains for the infirmary.

The next project he asked us to do was decorations for the dining hall of MCI-Concord. The chef had normally done the decorations. Well, we decided to bring the smells of Christmas to the inmates. A number of us went out into the woods and got huge bows of pine and pine cones and we did great sprays of these wonderfully fragrant pines, 24 of them to hang between each of the windows in the dining hall. Well, we arrived in Mary McClintock's van with these 24 sprays and a correctional officer got into the van with us and brought us around to the dining hall. We unloaded the greens, we put them up, it looked fantastic, we got back into the van and the correctional officer said to Mary, "This is a very nice vehicle that you have outfitted for camping and all." She said, "Well, my husband is a rock climber and we go camping and so we use this vehicle." He said, "Oh, that's very nice," and he lifted up the seat of the box he was sitting on as we went in the van and there were enough rope and pinions and various kinds of climbing equipment that probably could have taken about 15 men up and over the wall. He turned absolutely white and said, "Oh, ladies, please get out of here." We knew our secret was safe that he would not tell about our discretion that we were totally oblivious to because it was actually his responsibility to have checked out the van. That was my initial introduction to the prison.

This was probably around 1967 and it was a time at the institution when the inmates were really very, very active doing lots of different programs that were underway. Commissioner Boone was at the helm at that time. There were programs like the Concord community Inside-Outside newspaper that was the oldest prison newspaper in the country. There was a chaplain's discussion group which had programs involving fellowship. The Peaceful Movement Committee that Clem Smith was so active in was very prominent at that time and doing a lot of good work. Well, after we did these two little projects I began to explore with the superintendent other kinds of programs that we could do to link up the community with the prison and to make use of some of the resources we had in the community for the prison.

We established a number of different things. We thought that the program should be larger rather than just something coming from the First Parish Church, so we involved a number of people in the community and it was called the Concord Correctional Resource Group. The kinds of programs that we did at the time included establishing a file at the library for all kinds of information having to do with prisons, offering an art course and then having a show at the Concord Library of the art work. A weekly column in the newspaper called Notes on the Wall written by Clem Smith, a reception for some of the officials at the prison to meet some of the officials in the town. We started again the historical precedent of having the superintendent march in the April 19th parade and through our committee Nancy and Art Turner offered an adult education course about prisons. So it was really not actual programs that we were doing for the inmates, but it was an effort to sort of link up the community and the prison and to make use of the resources available.

This was going along swimmingly and we were having a great deal of fun. Then all of a sudden and it seemed out of the blue to us, we were asked not to come in to do any programs and all the other programs that were being done were asked to leave the institution. We discovered afterward the fact that it was such a liberal time, the control wasn't sufficient at the institution for having volunteers in there safely. There were some areas in the prison where the inmates were in control. So at that point in time there were 400 inmates in the institution and our involvement with the institution really ended in the late ‘70s. We were working at the large institution, MCI-Concord and hadn't put a foot in the door at the Northeast Correctional Institution. I believe they were connected at that point in time, they were all under one system, but we were just interacting with the main prison.

Jean — My involvement started in the late 1970s. I was on the social ministry commission at Trinity Church and our chairman Dr. Charles Willie asked us to help find what our focus is. This very wise man who helped desegregate the school systems in Boston and other major cities around the country said, "You know you don't need to go to Boston to find a need, we have it here in our own backyard, the prison." That just somehow rang a bell with me. I then wanted to find out what could be done. Knowing that we weren't really welcome behind the walls, I made an appointment to see the Superintendent of the Northeast Correctional Center, which is locally known as the farm or NCC. At that time it had become a separate institution. It was both a minimum security prison and a prerelease, which meant that men who slept the night at the prison could go out and be employed in the community during the day. I talked with Superintendent Robert Walsh and asked if there was some way in which those of us in the community could be helpful in his institution. He thanked me very much and said, "Well, he would think about it but he really didn't have any ideas." So we went along wondering how we could become involved.

Then in the early 1980s three students from Boston University School of Theology asked if they could come and talk with us at Trinity Church about finding a way for seminary students to get an experience in the prisons. We invited other churches to come too and at that meeting we also had the Protestant chaplain of the Northeast Correctional Center. At the beginning of the meeting the Protestant chaplain indicated that there was only a few hours a week available and that he was really so busy that he didn't have time to supervise seminary students. By the end of the meeting he said, "You know the needs there are so great that I would welcome any involvement." So from that representatives of three of the churches, the First Parish Church, Trinitarian Congregational Church, and Trinity Episcopal Church agreed to form a task force that would explore what they could do. We met probably for over a year trying to figure out what we could do. Finally the Protestant chaplain said to us, "Well, why don't you gather together members of your congregations and come up and sing Christmas carols?" We thought can we really find anybody else who would do this with us? But we persuaded 40 people and we had a remarkable time. There must have been 60, 70 or 80 inmates and we were all there together, mixed in together singing in the dining hall at those metal tables and hard benches and enjoying making music together and enjoying exchanging our appreciation. That began what has become an annual tradition from when it started in 1983.

The next year we were able to get a divinity student whose name was Barbara Edgar. She had grown up in Carlisle and was very familiar with the institution. Part of her field work was to spend some time for Christmas and to find out what our parishioners do. She found that part of a life skills curriculum was focused on finding a job. She worked to get that course given. So there were about 25 members of the community who became familiar with the curriculum and went for I think four sessions and helped the inmates learn how to use the want ads, network with friends and relations, how to fill out a job application, practiced telephone interviews and face-to-face interviews. This was in 1986 and that was really the first program. That summer we came to the realization that it didn't work to have a seminary student who left at the end of the season. We needed somebody who was familiar with the community and who would build programs. We advertised for the position. We had the three churches willing to help with a stipend for such a person. We were able to persuade Di Clymer to apply. We interviewed everybody but there was just no question. In so many ways the ideal person was Di. So she took over in the summer of 1986 and since my husband and I were going to be out of town for the next nine months, Rebecca Sheehan was persuaded to become Chair of what was at that time called the Concord Prison Ministry Task Force. It was there the programs began to grow and develop expanding in the community under Di's leadership.

Diana — It was very fortuitous coming back to prison work after being away from it for a while. I quickly found out and realized that we would get along further and the need is greater if we did something in the educational area. There was a little bit of a turf issue with the chaplains that were at the NCC. They had their programs and space was limited and it probably would not have been a good idea to offer any more religiously oriented kinds of programs. The job search program had been well received by the administration and it was something they found useful. So we contacted a number of resources one of which was in Boston, Concord Correctional Course, a comprehensive offenders employment resource service, and they work with inmates that are going back out into the community. So they worked with us and really beefed up the initial program that had been put in place and made it more specific to the needs of what the inmates were going to be returning to society. The pattern remained the same of bringing people in from the community to get them to take the program with the inmates and that way learn the curriculum. Their being participants along with the inmates gave the entire program a sense of community. It wasn't a program that we were doing to the inmates or just for the inmates but this was a program that we were doing with the inmates. It heightened the sense of how valuable it was to see the community people coming in to take this program too. Once the volunteers knew the curriculum then they could take a turn in teaching the program.

We expanded the program. We offered an in-depth program on resume writing. We then offered a program on career exploration, and once a week we would bring in four different people from the community to talk about their careers. What was it like to be a landscaper, what was it like to start your own business, what was it like to work in food services and so forth. They would just talk about the pluses and minuses of their work and the inmates could ask questions and the inmates could get a sense of other occupations that they might be interested in.

The job search program led us into thinking about other life skills kinds of programming, such as money management. We worked with the extension service over here on Stow Street. The thought was in trying to develop these curriculums that we really should make use of all the resources we have in the community, so if I possibly could, I would get an expert or program that was already intact to use and then just build up the volunteer team with that. So they helped us formulate the money management program and it was eight sessions long. The men learned how to budget, learned about banking. One of the things that always surprised everybody who became involved in the programs was the range of abilities and interests and skills that these inmates had. Some of them knew all about banking. Some of them knew absolutely nothing so we had to pitch all these courses toward the middle and use volunteers to bring along those who needed extra help. The main thrust of every single one of the programs was to help build some self esteem and confidence. We also started programs in tutoring so that the men could get their GEDs. We were tutoring men in English and math and started an English as a second language program. We went to the Concord Arts Council and asked for a grant so we could give a stipend, a small stipend for artists to come in and teach art. That was a very fine program and I think it was very well received from the artist's point of view. They'd never had an opportunity to go into the prisons. A lot of them got very excited in seeing the art that these inmates could do. That resulted in a show at Emerson Umbrella.

We also started a computer program and a calligraphy program. For all the programs we were doing at the end we would give a certificate to the men to say that they had completed the program. It seemed to mean so much to them to receive this certificate. The men had failed in so many different ways. They had failed in education, they had failed in relationships, they had failed financially, failed their families, they even failed in crime, and somehow to receive a certificate that they had accomplished something made such a difference. It was so visible to all of us who were working with them. I asked Martha Rouse if she would come in to see the men receive their certificates. She had done all these certificates for all these programs. She was very nervous about coming in as she was very shy. Some of the volunteers were nervous about coming in. I told Martha that I promised her an interesting experience and that I would be with her. So she came in and saw the men receive their certificates and began talking to some of the men at the end of the program. I approached her and asked her if she would be willing to lead a calligraphy class and she said, yes, she thought she could. With a little hand holding, she started a calligraphy class. It surprised us all because you wouldn't think of trying to teach calligraphy to a bunch of hardened criminals but it was actually the quintessential perfect thing to be teaching. In four sessions the inmates could learn the skills. It was very exciting to them. They not only learned the skills but they also had something that they would have for the rest of their lives. They could do it in their leisure time which they had a lot of in prison or they could do it to make money. So it was a very successful program. You could hear a pin drop watching these men so diligently working on their letters.

Then MCI began to hear about the programs we were doing at NCC and meetings began over there to get involved with their educational team. We met with the director of treatment and started to develop some of these courses across the street. So by 1988 we had a great cadre of people doing volunteer programs at NCC and to some degree at MCI.

Jean - MCI became a place where all the offenders who were sentenced to state prison would come for classification which meant that they would be there for the time that it took to gather their court records, past criminal records, to test them educationally, assess their physical, medical and psychiatric needs and then to determine what level of security they needed to be placed under. Then, try to find an open cell at an appropriate facility because of the prison population explosion.

I think it's helpful if we examine 1988. George Bush was running as the Republican candidate against Michael Dukakis who was then Governor of Massachusetts. During the course of that campaign an inmate from NCC was allowed out on furlough. The furlough program had been in place for many years. Through it men were allowed to go out for a day or several days and spend time with their families or look for a job or look for a place to live, in other words keeping up the family and community contacts. This was an extremely worthwhile successful program with a success rate of 99%. In other words practically nobody did not return. But unfortunately an inmate named Willie Horton went out on furlough and did not return and he committed an additional crime. The Republican presidential candidate picked this up and accused Governor Dukakis of being the cause. This became a cry that in no small way threatened this program. The net result was that the open door policy of the prisons was changed and more and more security rather than rehabilitative programs became instituted.

When Governor Dukakis was succeeded by Governor William Weld this emphasis was raised to a much greater level. Security was the all important thing. Counseling programs and rehabilitative programs were almost eliminated. The education budget was reduced to a quarter of what it had been. Judges were being urged to sentence inmates to longer sentences and the result was that the prison population was mushrooming and the space was not. The 1980 population at MCI-Concord was between 400 and 500. It grew to the point where eventually there was over 1300. The cells were all double bunked. The program space where the educational programs had been, woodworking, auto mechanics, a variety of things, that space was turned over by putting mattresses on the floor. There were mattresses on the floor of the corridors in the counseling area.

Governor Weld's Commissioner of Corrections Barry DuBois, when he was in the federal prisons system, closed all the farms that had been associated with the system. Soon we found that there was talk of closing down the Northeast Correctional Center as well as other prisons in Massachusetts. Our group was very much opposed to that because for one thing this was the last remaining dairy farm in Concord. There had been quite a number of them in the old days.

The experience the inmates had working on the farm with the cows inculcated good work habits. They had to get up at 4:00 a.m., be there, milk those cows, cows depended on them. They had to take care of the little calves that were born. Often an inmate would be assigned one particular calf. It was his responsibility. He had to feed it with a bottle, nurture it along until it could take care of itself. For some that was an opportunity to be caring and nurturing to another living thing.

They learned how to repair old farm equipment because there were no funds to buy new tractors and they became good mechanics. And another fact was that the staff in the barn treated them as human beings, didn't put them down, had expectations of them and expressed appreciation when they did something. This again was rare at that time and it meant a great deal to them. They also learned how to build buildings when they needed an additional farm building.

What is now called Concord Prison Outreach as opposed to Concord Prison Ministry Task Force made strenuous efforts to get our elected town officials to inform prison officials whether Concord wanted this farm to continue. At this point we involved the legislature also. In fact our State Representative Pam Resor inserted in the Department of Corrections budget words that said that it must spend at least so much on farm operation. I think that happened two consecutive years. Eventually the Department of Corrections called in the experts from the Agricultural School at University of Massachusetts and they were told that this was such a model of a dairy operation, a herd of over 100 healthy animals that produced an amazing amount of milk which is then pasteurized and sold at cost to other prisons in Massachusetts. They said this operation should not be closed down. That was the decision eventually that the Department of Corrections made for which we are grateful.

Diana - When I first became involved with MCI-Concord, there were nine teachers teaching 400 inmates. At this point in time because of the emphasis on security and reduction in treatment stuff, we ended each year watching these teachers get fired or go to other institutions. So we ended up with a situation with one and one-half teachers in the program for 1300 men. So that gives you an idea of the lack of programming that was going on in the institution. One of the ways in which Concord has been unique and one of the things that was very fortunate was that we have established such a wonderful rapport with the administration in both of these institutions in Concord. Even though the tenor of the times in other institutions and in the Department of Corrections itself was restrictive of programs, the directors of treatment at these two institutions were very grateful for whatever we could muster. So we had quite an open door to bring all kinds of things in. The other thing I should note is that not only were we grateful we had developed this rapport with the administration, both the security administration, directors of treatment and superintendents, but we also had the historical background in our favor. So that each time a new superintendent would come to the institution, I would sit down with the superintendent and I would tell him about the history and how the townspeople petitioned the legislature to have a prison built and the kind of community involvement that had occurred over the years. They really felt a sense of becoming part of a greater whole not just their institutions, but they were part of the Concord community and the Concord community had been part of the institution and that we had a model to maintain.

I was delighted to see that a lot of these superintendents asked me to drive them around town. They spoke at different occasions, so we tried to foster that sense of being part of a larger community at every stage of the game. Even though in other institutions programs were missing, because of this good rapport, and the historical tradition that we had, we developed all kinds of programs. We also were given an office at the West Concord Union Church. The West Concord Union Church had been coveted by members of the prison officers many, many years ago and the church felt that they would very much like to offer the Prison Outreach office space in their church. So we had the office space to use to again bring people out, to orient them, to get them involved and so forth.

I'm going to run down a list of some of the different programs that we have done. I would like to preface it by saying that the Concord community has been such a giving community all these many years and so curious about the prison, that it was very easy to get these programs established using talent that we already had in the community. For instance we wanted to do a health program. The institution actually came to me and asked me if we could do a health series program. It was something that they needed for accreditation. It was to be a program once a month so I needed 12 doctors to come and speak, one a month. I made 13 phone calls in order to create this program that we needed. I say that because I think it shows that when you extend the invitation to somebody in the community, I found every single time that people were curious and willing to entertain the possibility of coming in and doing a program. The 13th doctor said he had a conflict but he did it the next year. So I found just in meeting people around town at various occasions I would talk with them about the programs that we were doing. I would learn about what their particular interests might be, what their avocation or what their career was and see if they might be willing to come and teach a course at the prison. They would stop and think, wow, really? Teaching a course on stocks and bonds really? I said, "Well, you might find it quite interesting." And in fact we had a course on stocks and bonds. At one institution the group that had signed up knew absolutely nothing about stocks and bonds and the next time we offered the course in another institution, the group had been wheelers and dealers of stocks and bonds and it was a whole different kind of program. The man who gave the course had the best time. Absolutely one of the things we found was that people who came in to volunteer would come in expecting to give something to the inmates, and each and every time they would come out saying how much that they had received and how excited they were. At that point in time we were doing programs at both institutions. By 1988 we were in full swing at both institutions.

So let me run through a list of some of the programs that we were offering. We offered photography, Dave Chase did a program on photography which was fascinating because you weren't allowed to bring cameras in but that didn't deter us. We still talked about the principles of photography and design and so forth. We also offered a program in journalism. That was in conjunction with trying to keep alive the Concord community Inside-Outside newspaper. A program called chorus. Marsha Martin came in and led a group of men who became the NCC chorus and they sang at various occasions. We then had not only a caroling night but we had a valentine party at Valentine's Day and we also had something called the Spring Fling where Tom Ruggles came in and played with his group and the chorus participated in all of those. Someone came in and taught juggling. We also were starting at that point the holiday shoebox project which has become a mainstay. Once a year people in the community decorate a shoebox and fill it with items that are allowed to come in, about 10 different items and they are given to the men at the holiday season. We had a program on yoga, relaxation techniques, and literacy. Someone came in and did a program on income taxes. Another program on insurance. We started a program on smoking cessation. We had a speech therapist and worked with some men who had speech problems. Robin Moore taught a program in writing. Another program was how to start your own business. We had a separate program on communications. A program was started through Emerson Hospital on Tools of Recovery, a substance abuse program. Other programs were how to read legal contracts, origami, comparative religions, compulsive behavior, decision making, chess, first aide, a book discussion group, a program that Jack LaMothe did on taking charge of your health, black history, speaking effectively. Anyway, it was a long, long list. Each and every time we would find somebody who had a skill to offer, and come in and begin the program. What we were realizing in doing all these programs was that the core of the program was building self-esteem. Lynn Ouderkirk and Betsy Grennan started a program on parenting. That program on parenting highlighted this need for building self-esteem. Through that work we decided to try and find a program that really specialized in building self-esteem, and that led us to the discovery of alternatives to violence program, which is an experiential program that takes place over a weekend.

That program has probably become one of the most powerful programs that we offer. The parenting program expanded to not just offering a parenting program but a father support group came out of that and now also happening is a program called family relationships where they work with the spouses and so forth. Another program that got started was healthy survival skills. That also was an experiential program. And a program called breaking the chains which was to bring in the black community from Boston to network with the black churches in Boston to bring volunteers in from the black community to work with the inmates so when they came back to the community they would have some familiar faces to reenter with.

Out of the alternatives to violence program we had a participant who left her session and said, "You know the work that I am doing in the area of forgiveness, I think would be perfect here." So we sat down with her and found out what she was doing and she ended up giving a program on forgiveness in the institution. She was fascinated with what evolved from that program just as all the other volunteers were stretched and excited about working with inmates with their program. She gave several courses on forgiveness and out of those courses a book developed on the "Emotional Awareness, Emotional Healing" was the name of the course, but the name of the book was Houses of Feeling. That book has been the basis of the emotional awareness, emotional healing course for a number of years. It is an incredible experience for both the volunteers and the inmates who are taking it.

Jean - Because Concord prison was originally set up as a reformatory and a judge wanted to send a youthful offender to Concord, the idea was keep him there until he learns to mend his ways and you think he is a good risk to go back out. So the Concord sentences were indeterminate sentences. The judge may say sentence to Concord for up to 10 years, but the prison authorities could decide after two years that he could get out. Over the years the inequity that resulted was apparent, and there was strong feeling with the public that this was not fair. One judge would order one length of sentence and another judge would order another length of sentence, whatever they said it was a Concord sentence and you couldn't count how long the inmate would be in. Where if it was a Walpole sentence for 10 years, you knew they would probably be there for 10 years. There was a strong movement in the legislature to have what they call "proof in sentencing" legislation. Through that the Concord sentence was eliminated and there was a new range of sentences adopted, actually part of that movement is to create guidelines that would apply to all judges. They have a specific range of sentences that they are all bound by. But while the sentencing commission appointed the extensive report and study, the recommendations have not been passed by the legislature. By eliminating the Concord sentence most inmates are serving much longer terms and that again has increased the prison population.

But to return to what we tried to do as a result of finding out the education budget where the department had cut, cut, cut for six successive years, we started meeting with the director of prison education to work out what would be a constructive form of action that would help increase the funds that are made available so that they wouldn't have to keep cutting the number of teachers. We became aware of a model of legislation which had already been passed at the impetus of the sheriff of Suffolk County jail which applied to all county jails which required that there be a mandatory education program for all those who were not literate. So we formulated a proposed law that was very similar to that only that it applied to the state and we brought this idea to our State Senator Lucile Hicks and our State Representative Pam Resor and they both were willing to push for this to be passed. We found it very interesting that we went to testify before the legislative committee on criminal justice, and to be called in when they were drafting and redrafting this bill. It got passed by both the House and the Senate but when a conference committee met to reconcile the two budgets, they eliminated our package. Lucile Hicks was able to get that through and the Department of Corrections found itself with the mandate of trying to plan a program in education which they did. In 1996 they had a pilot program with three teachers in Norfolk, which is a men's facility, and two teachers at Framingham which is a women's facility. That was to emphasize that those who did not have the basic literacy skills which meant below sixth grade level.

As a result of this, the Department of Corrections did have for one year a pilot program, and we are still waiting to learn exactly how to apply the lessons learned from that. They did find that there were men who refused to participate. They found that there were some remarkable strides made by those who did participate, not in all cases but in a significant number of cases. They began to develop incentives and sanctions that would try to dissuade those who are reluctant or who had bad experiences as a youth to at least give this a try.

But I think our efforts to make legislators aware of the importance of education and of the drastic cuts in the budget did make an impression and in the following year there was almost a million dollar increase in funds that were put into the corrections budget. We don't want to give up on this because there is so much more that we could have done.

Diana - One of the things that we found when we were doing this legislative effort was that we had to be vigilant and actually pick up the pace educating people so we would have citizen support in backing this kind of legislation. So we had various kinds of forums. We had forums right straight through since the beginning of Concord Prison Outreach because this was our network of getting volunteers. We would go to set up a forum at different faith communities to talk about the volunteering needs in the prison. We should say that in terms of the structure of Concord Prison Outreach it was based, the organization structure, on support from all the faith communities in Concord and many of the surrounding towns. They are the ones who have private funds for program materials and they are the ones from whom we have gotten most of our volunteers. At this point it's a wonderful cadre of people in town who have become active.

The kinds of community forums that we would do would be not only at the different churches where we would be talking now about legislative issues as well as volunteer opportunities, but we would also talk with the League of Women Voters. I met with Newcomers Club, the Rotary, the Lions Club, the Concord Clergy Lay group. In each case when we went to speak we would bring somebody from the institution, an inmate or a former inmate if we could, and a volunteer to sort of share the different aspects of the work and why it was so meaningful to become involved.

Jean served as a member of the Concord Clergy Lay Group and met with them to make them aware of program needs in the institution. The community as always was very eager to hear what was going on. We spoke to Rotary at least twice, the Lions Club a couple of times, the Chamber of Commerce a couple of times. They wanted to hear over and over again that this was important work.

Jean - Another way that we did that was to offer a course through the adult education program called "These are Our Prisons," and we did that four different times over the years. One year we gave a course called "Our Criminal Justice System," which involved judges and members of the parole board, probation people to try to help people understand the whole system so that they could see the interconnection with parole, because parole in the past has been a very important incentive for prisoners to be on their best behavior so that they can get out earlier on parole. Unfortunately in recent years the emphasis on not letting inmates on parole and many inmates being turned down for parole when they have worked so hard to prove that they are different from when they came in and want to leave doesn't seem to be recognized. Part of that is because the political climate is such that people running for office particularly governors don't want any chances taken because they remember Willie Horton and what that did.

Many people don't understand that an inmate can start at a maximum security prison and move through the system to a minimum security. They can move from maximum to medium to minimum to prerelease which is a very, very helpful step between minimum security and prerelease where it is much more community based with jobs.

Another one of the public forums that we put on was restorative justice which is a relatively new term and the basis for restorative justice programs is the idea that when a harm is done, it's done to a victim but often the community is also harmed by that crime. There needs to be a restoration of relationship between the defender, the victim and the community. The restorative justice programs try to accomplish that. So we had a program that was attended by over 200 people from about 48 different towns. There were actually two programs because the second one was an opportunity to hear a judge from Canada speak about how he discovered this from the native Indian traditions in Canada which has been used in a variety of settings and now is in use in Franklin County in western Massachusetts. After an offender has admitted his guilt, the judge may ask for participation from the community for determining the sentence. Included among those who gather who discuss what happened, why, what should be done about it are the defender, his friends and family, the victim, his or her friends and family, police, prosecutors, defense attorney, probation and any other members of the community who are interested. People sit in a circle where each person has the chance to speak and when they are speaking everyone else listens. As some symbolic thing, a feather is passed around and each in turn speaks from the heart or passes. But the effectiveness is really amazing. Out of the process really emerges consensus as to what happens and how he will be sentenced and what needs to happen in the future to prevent that kind of behavior for that particular offender or others. The community members take responsibility for a solution, be that finding a job for the offender, or drug counseling or education or whatever is needed and for helping make things right for the victim. So that's restorative justice.

The adult education course was offered at Alcott School. A lot of effort went into that by a committee of people that reached outside of Concord. We had a knowledgeable lawyer who was a specialist in mediation, Father Fleming, a priest at Our Lady's Church in West Concord, the League of Women Voters and sponsoring institutions. I think one of the evidences of the community recognizing what we have done in Concord Prison Outreach under Diana's leadership was when the Concord-Carlisle Human Rights Council chose this organization to receive their Climate for Freedom award which is given biannually to a community group that they feel has done the most in human rights. Diana and I both feel that it really is a tribute to this community and all the people that have responded so generously to requests of getting involved with the two prisons.