A Moving Story

by Leslie Perrin Wilson

Curator of William Munroe Special Collections at the Concord Free Public Library, Concord, Massachusetts

Rick Wheeler — a local resident whose family connection with Concord extends back to the English settlement of the town — is fond of quoting his grandfather, Wilfrid Wheeler, on the most popular winter activities of the 19th century. Grandfather Wheeler identified the "favorite winter sport" of Concordians as "moving houses and suing the neighbor." We simply accept the litigiousness of our ancestors as the expression of an enduring aspect of human nature. The frequency with which they moved buildings before the advent of gasoline engines and power tools, however, impresses us more.

Rick Wheeler — a local resident whose family connection with Concord extends back to the English settlement of the town — is fond of quoting his grandfather, Wilfrid Wheeler, on the most popular winter activities of the 19th century. Grandfather Wheeler identified the "favorite winter sport" of Concordians as "moving houses and suing the neighbor." We simply accept the litigiousness of our ancestors as the expression of an enduring aspect of human nature. The frequency with which they moved buildings before the advent of gasoline engines and power tools, however, impresses us more.

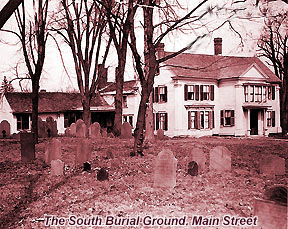

During the 19th century, many Concord buildings were moved from one place to another, sometimes over significant distances, occasionally more than once. Examples of old structures that (to borrow Thoreau's words) "travelled a good deal in Concord" include the Edward Bulkeley House at 92 Sudbury Road, believed to have been moved in 1826 from Main Street; the Emeline (or Emmeline) Barrett House at 30/32 Court Lane, which originally stood on Monument Square, was moved in 1820 to the corner of Monument Street and Court Lane, and later to its present location; the old Concord Academy building at 25 Middle Street, moved from Academy Lane after Middle Street was laid out (1850-1851); the Nathan Brooks House (or Black Horse Tavern) at 45 Hubbard Street, which formerly stood at the intersection of Main Street and Sudbury Road, and was moved in 1872 to allow construction of the Concord Free Public Library; the Thoreau birthplace at 341 Virginia Road, which was moved from the site of what is now 215 Virginia Road in 1878; and the Block House at 57 Lowell Road, moved in the winter of 1928-1929 from the present location of the Middlesex Savings Bank (64 Main Street - pictured below, left).

Nowadays, it is often easier and cheaper to raze an old building, haul it to a landfill, and put up a new one in its place than it is to move and recondition it. People sometimes purchase an old house specifically for its lot, with the intention of demolishing it and erecting one more suited to modern needs and wants. But our Yankee predecessors were less willing to tear down buildings that had required a significant investment in materials and labor to construct. Without modern tools, equipment, and techniques, many man-hours were required to accomplish tasks that are far less time-consuming today. In fact, during the 19th century, it made good economic sense to move and recycle a building no longer wanted on its original site.

The cost of labor in 19th century America was relatively more expensive than elsewhere. David Stevenson, a Scottish civil engineer born in 1815, traveled in the United States and Canada for three months and published his professional observations in 1838 in his Sketch of the Civil Engineering of North America. Noting that American laborers earned more than twice the daily wage of their British counterparts, he wrote, "In consequence of the great value of labour, the Americans adopt, with a view to economy, many mechanical expedients, which, in the eyes of British engineers, seem very extraordinary." Chief among these expedients was the moving of houses, to which Stevenson devoted a whole chapter of his book.

In addition to changing economics, the modern complications of telephone and power lines, plumbing connections, heavy traffic, and the necessity of obtaining special permits have all contributed to the present-day disinclination to move old buildings.

In the 19th century, buildings might be moved disassembled, partially disassembled, or intact. As John Obed Curtis explains in his Moving Historic Buildings (1979; reprinted 1991), these same methods are still used today to preserve historic buildings from demolition.

Total disassembly involved the dismantling of a structure piece-by-piece. Each piece was marked so that the various elements could be put back together as they had come down. If the building had a foundation, the stones could be marked, removed, and reused, or the building could simply be reconstructed on a new foundation. Total disassembly involved the loss of a building's original plaster and so was not the method of choice when the preservation of interior walls was a priority. It was, however, well suited to the moving of barns, sheds, and other minimally finished buildings. There is at least one antique barn in Concord today in which the clearly marked pieces of another old outb uilding have long been stored.

Total disassembly involved the dismantling of a structure piece-by-piece. Each piece was marked so that the various elements could be put back together as they had come down. If the building had a foundation, the stones could be marked, removed, and reused, or the building could simply be reconstructed on a new foundation. Total disassembly involved the loss of a building's original plaster and so was not the method of choice when the preservation of interior walls was a priority. It was, however, well suited to the moving of barns, sheds, and other minimally finished buildings. There is at least one antique barn in Concord today in which the clearly marked pieces of another old outb uilding have long been stored.

From the architectural historian's point of view, total disassembly as a modern preservation technique has merit, even though it involves the destruction of original plaster and mortar. As Curtis points out, the process allows examination and documentation of the various layers of a structure. For example, the dismantling in the summer of 2001 of Concord's Ball/Tarbell/Benson House (formerly on Ball's Hill Road) permitted exploration of how this early house had evolved over time. (The house was disassembled to save it from demolition and will remain in storage until circumstances are right for its reconstruction on another site — see here for more information.)

Partial disassembly involved the removal, marking, and transportation of structural components of a building rather than individual pieces. This method was less time- and labor-consuming than total disassembly. In his account of methods of structural moving for preservation purposes, Curtis describes the partial disassembly of a simple braced frame building of one and a half stories. The interior finish work, plaster, lath, and floors are removed first, then the roof. (As with total disassembly, the original plaster is lost in the process.) Non-loadbearing interior walls are handled as discrete units. The four exterior walls and two gables each comprise a separate unit.

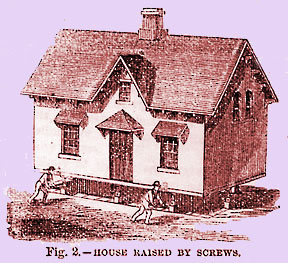

There were various methods of transporting an intact building in the 19th century, but before it could be moved it first had to be raised up off its original foundation. This was commonly accomplished by the use of screwjacks. Sections of the foundation were removed to allow placement of the screwjacks under the sills. A large building required more screwjacks than did a small one.

Sometimes little complicated engineering beyond the raising of the building off its foundation was necessary. Under the right conditions, sheer animal power could accomplish the rest. The Jones/Channing House at 325 Main Street, for instance, was moved in 1867 from its original site (the lot now numbered 252 Main, which formerly accommodated two houses) on a sled pulled by twenty-two yoke of oxen. As Wilfrid Wheeler's comment about the favorite winter pastimes of Concordians suggests, ice and frozen, snowy ground eased the travel of buildings over the landscape.

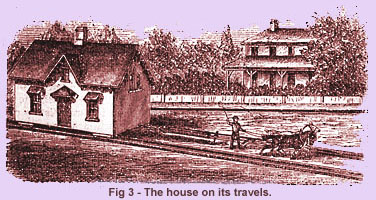

Often, however, additional engineering measures were required to transport a building once raised off its foundation. As described in wonderful detail in an anonymous article on moving houses in the American Agriculturist for November, 1873, one much-used technique was to place the raised structure onto rollers and to move it to its new site over timbers. The rollers consisted of wooden carriages fastened beneath the building's sills (by means of spikes projecting upward from the carriage) with wheels attached to the underside of the carriages. The rollers traveled over heavy wooden timbers placed beneath the raised building. By means of a rope and pulley or capstan arrangement, a team — generally no more than two animals were required — pulled the building along the timbers. As it moved forward, the timbers from behind were taken up and replaced ahead of it. As long as the move was well managed, the interior plaster would remain uncracked throughout. Scotsman David Stevenson marveled at how successfully even houses with items hanging on the walls were moved.

Often, however, additional engineering measures were required to transport a building once raised off its foundation. As described in wonderful detail in an anonymous article on moving houses in the American Agriculturist for November, 1873, one much-used technique was to place the raised structure onto rollers and to move it to its new site over timbers. The rollers consisted of wooden carriages fastened beneath the building's sills (by means of spikes projecting upward from the carriage) with wheels attached to the underside of the carriages. The rollers traveled over heavy wooden timbers placed beneath the raised building. By means of a rope and pulley or capstan arrangement, a team — generally no more than two animals were required — pulled the building along the timbers. As it moved forward, the timbers from behind were taken up and replaced ahead of it. As long as the move was well managed, the interior plaster would remain uncracked throughout. Scotsman David Stevenson marveled at how successfully even houses with items hanging on the walls were moved.

In some cases, a building might be moved by a tongue and groove type of setup rather than on wheels. It would slide over beams with projections that fit upward into grooves in the wooden pieces above, onto which the sills were fastened. The beams were greased to facilitate movement. More complex situations required special preparations, such as the construction of cribwork to manage the moving of a building down a hillside. As time went by, other forms of power besides animals were used for transportation.

Images: Line drawings - American Agriculturist, November, 1873.

Photo of Block House: Special Collections, Concord Free Public Library

Article appeared in the Concord Magazine, by Hometown Websmith, Concord, Mass., November 1998. This article was previously printed in the Concord Journal with title, Many of the Town's Oldest Houses have Moving Stories.

©2015. William Munroe Special Collections, Concord Free Public Library, Concord, Massachusetts.