VII. JOHN BROWN

Militant abolitionist John Brown first came to national attention during the conflict over whether Kansas would become a free or a slave state. A number of Concord citizens—including some, like John Shepard Keyes, who had not played a prominent role in the reform arena—supported Brown's crusade for a free Kansas.

In the 1850s, Kansas was rife with violence. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 left the question of whether or not slavery would be allowed there to be decided by settlers of the territory, abrogating the Missouri Compromise of 1820. For a time, Kansas had two governments, one that permitted and one that outlawed slavery. As abolitionist and proslavery settlers packed the territory and subsequently clashed, lives and property were lost.

John Brown—a tanner, sheep farmer, and businessman whose long-standing abhorrence to slavery was permeated with religious fervor and an unbending sense of righteousness—went to Kansas in 1855 to bring arms to his sons, antislavery settlers who feared attack by the proslavery terrorists known as the "Border Ruffians." He subsequently threw himself into the protection of free state settlers and into retaliation against proslavery attacks. On May 24, 1856, in the wake of the proslavery sack of Lawrence and of the vicious beating of antislavery senator Charles Sumner on the floor of the United States Senate by South Carolina congressman Preston Brooks, Brown led a small party to Pottawatomie Creek, where five proslavery settlers were butchered. With his men, he waged a guerrilla war against bands fighting to establish Kansas as a slave state. He joined Captain James Montgomery in free state action on the Kansas-Missouri border, and in December of 1858 led a raid in Missouri which resulted in the seizing of slaves and the death of a slaveowner. Through all of this, he mulled over the idea of establishing an escape route for slaves from Virginia to Canada (which he had been considering for years) and schemes for an armed slave uprising in the south.

Brown's Old Testament aura and simplicity of manner impressed many as he spoke to crowds all over the northeast to raise funds for the purchase of arms and supplies necessary for free state settlers and, ultimately, to outfit his militia for his southern offensive. Support came from state Kansas relief committees and other organizations, and from individuals as well. None but his innermost circle—the Secret Six, who included Concord's Frank Sanborn—knew that donations made in the late 1850s would be used for a raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia.

Brown first came to Concord in March of 1857 at the request of members of the Concord Ladies' Antislavery Society, who were planning a fair on March 10th and 11th. Their invitation was extended by Frank Sanborn. On his first day in Concord, Brown dined with the Thoreaus and met Emerson, who invited him to his home the following night. On the 11th, he spoke at the Town Hall.

Brown returned to Concord as Sanborn's guest on May 7, 8, and 9, 1859, again talked with Emerson and Thoreau, met Sarah Alden Bradford Ripley at the Old Manse, and on May 8th addressed a local audience at the Town Hall. Bronson Alcott wrote of Brown on this occasion: "He tells his story with surpassing simplicity and sense, impressing us all deeply by his courage and religious earnestness. Our best people listen to his words—Emerson, Thoreau, Judge Hoar, my wife—and some of them contribute something in aid of his plans without asking particulars, such confidence does he inspire with his integrity and abilities." Alcott found Brown "superior to legal traditions and a disciple of the right, an idealist in thought and affairs of state."

Immediately following Brown's October 16, 1859 raid at Harpers Ferry, people everywhere struggled to make sense of the barrage of conflicting and sensational reports that flooded the press. Many—including abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison—were critical. When the details of what had happened in Virginia became clear, his supporters in Concord did what they could to draw sympathetic attention to Brown's situation and to counter his portrayal as a madman and a traitor. Thoreau prepared and, on October 30th, delivered his lecture "A Plea for Captain John Brown" in Concord. Later, he wrote a tribute that was read on July 4, 1860 by Richard J. Hinton at the John Brown commemoration in North Elba, New York (Brown's home). Emerson lectured on Brown and helped to raise money for his destitute family. Jointly, the two did much to promote the image of Brown as a saint and a martyr rather than a fanatic.

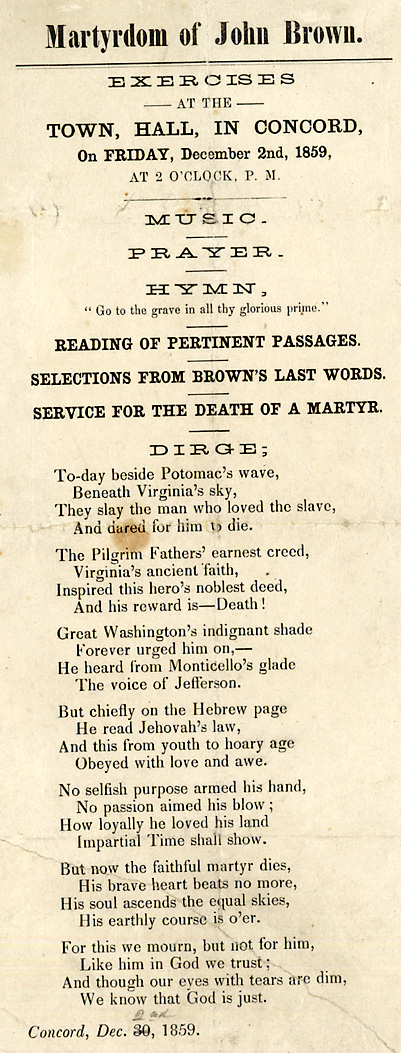

Not everyone in Concord revered John Brown. Nevertheless, Brown's execution on December 2, 1859 was mourned here with solemn public ceremony. John Shepard Keyes, who took part in the memorial service in the Town Hall that day, reported in his autobiography that the hall was crowded. The participants had agreed ahead of time to offer a program of readings so as to avoid the possibility of extemporaneously saying anything "treasonous" in the emotion of the moment. Rev. Grindall Reynolds of the First Parish read from the Bible, Emerson from Milton, Bronson Alcott, Keyes, Sanborn, and Judge Hoar from other texts. According to Keyes, Thoreau alone disregarded the plan and spoke his own mind. The singing of a dirge concluded the service.

The next day, Henry Thoreau assisted the return to Canada of Francis Jackson Meriam—one of Brown's conspirators who had fled to Ontario following the attack on Harpers Ferry—by driving the half-deranged fugitive (whom Frank Sanborn introduced to Thoreau as "Mr. Lockwood") to the South Acton train station.

Louisa Alcott's poem "With a Rose That Bloomed on the Day of John Brown's Martyrdom" appeared in the Liberator for January 20, 1860. In February, Sanborn arranged to bring Anna and Sarah Brown, two of John Brown's children, to Concord to attend his school. The Brown girls stayed with the Emersons when they first arrived in Concord, later with the Clarks on Lexington Road. In April, many townspeople rallied around Sanborn when federal officers attempted to arrest him to investigate his part in Brown's raid.

Not long after that, when the politically ambitious John Shepard Keyes went to Chicago as a delegate to the Republican convention at which Abraham Lincoln was nominated for the presidency, he discovered that his connection with the highly publicized Sanborn incident—part of the aftermath of Brown's raid—had given him name recognition well beyond Massachusetts. Later appointed a United States marshal, Keyes served as a bodyguard at Lincoln's inauguration and was present at the delivery of the Gettysburg Address.

Nationally, the Harpers Ferry episode further polarized north and south and moved the divided country closer to civil war.

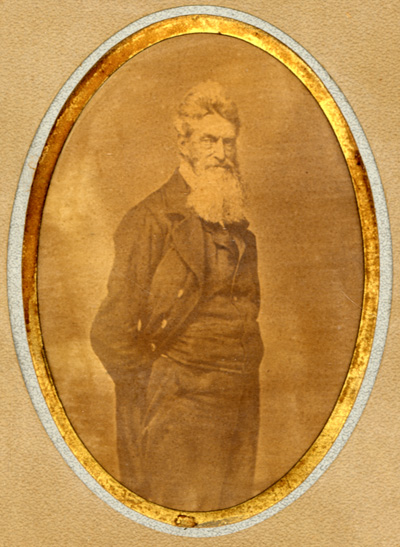

78. Early print from portrait photograph of John Brown, 1859. CFPL Photofile (matted and framed).

83. Brown's raid on Harpers' Ferry reported in Boston (transcribed from the Boston Daily Courier, October 18, 1859).86. Franklin Benjamin Sanborn. Account for expenses relating to Anna and Sarah Brown's attendance at Sanborn's Concord School, 1860-1861. From Franklin Benjamin Sanborn Papers, CFPL Vault Collection.

|

|---|

|

|---|

|

|---|

|

|---|