V. UNDERGROUND RAILROAD

By its very nature, the Underground Railroad—the person-to-person network through which blacks escaping from slavery in the south were assisted to freedom in Canada—was a clandestine operation. After the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 took effect, people who provided shelter, financial assistance, or transportation to slaves running for their freedom risked fine and imprisonment. It would have been folly for those involved in an illegal operation to keep records that might be seized and used against them. Primary documentation of the subject is therefore slim. Nevertheless, diary entries, letters, and later reminiscences provide some insight into the nature and workings of the Underground Railroad.

Many fugitive slaves passed through Concord in the 1850s. When interviewed by Edward Waldo Emerson in 1892, Mrs. Francis Bigelow recalled that "nearly every week some fugitive would be forwarded with the utmost secrecy to Concord to be harbored over night and usually was sped on his way before daylight." Ralph Waldo Emerson expressed a sense of defiance felt by the antislavery community at large when he advised his children, who had been assigned a school composition on building a house, "You must be sure to say that no house nowadays is perfect without having a nook where a fugitive slave can be safely hidden away."

The arrival of fugitive slaves in Concord personalized the antislavery struggle. Bronson Alcott wrote in his journal on February 9, 1847 that the temporary presence in his household of one black man seeking freedom gave "image and a name to the dire entity of Slavery."

Concord held a place on established Underground Railroad routes. Fugitives coming from Boston or from Fall River, Medfield, and Southborough passed through here on the way north. Local people provided hiding places for them until they could travel onward by train, collected money for their tickets, food, and other necessities, conveyed them to railroad stations (in Acton, Leominster, Fitchburg, and Lowell, among other places), purchased their tickets, and sometimes traveled part of the way with them.

The Thoreau home was a haven for fugitive slaves. Henry Thoreau escorted some who had been sheltered in Concord to trains northward. On October 1, 1851, he wrote in his journal, "Just put a fugitive slave, who has taken the name of Henry Williams, into the cars for Canada. He escaped from Stafford County, Virginia, to Boston last October had been corresponding through an agent with his master, who is his father, about buying himself, his master asking $600, but he having been able to raise only $500. Heard that there were writs out for two Williamses, fugitives, and was informed by his fellow-servants and employer that the police had called for him when he was out. Accordingly fled to Concord last night on foot, bringing a letter to our family from Mr. Lovejoy of Cambridge and another which Garrison had formerly given him on another occasion. He lodged with us, and waited in the house till funds were collected with which to forward him. Intended to dispatch him at noon through to Burlington, but when I went to buy his ticket, saw one at the depot who looked and behaved so much like a Boston policeman that I did not venture that time."

Among other Concordians who assisted fugitive slaves were Mary Merrick Brooks, who lived at the intersection of Main Street and Sudbury Road (the Concord Free Public Library site; the house now standing at 45 Hubbard); William Whiting, a Main Street resident (169 Main); blacksmith Francis Edwin Bigelow and his wife Ann (who lived across Sudbury Road from the Brookses, in the present 19 Sudbury); the Abiel Heywood Wheelers, farther out on Sudbury Road (387 Sudbury); Dr. Josiah Bartlett of Lowell Road (35 Lowell), who—like Thoreau, Abiel H. Wheeler, and William Whiting—transported escaping slaves to whatever railroad station seemed safest under the circumstances; and Miss Mary Rice (who lived at what is now 44 Bedford Street). Local tradition and the existence of a hidden cubby possibly used to conceal slaves on the run suggest that the Ball House (now the home of the Concord Art Association, at 37 Lexington Road) was also a stop on the Underground Railroad.

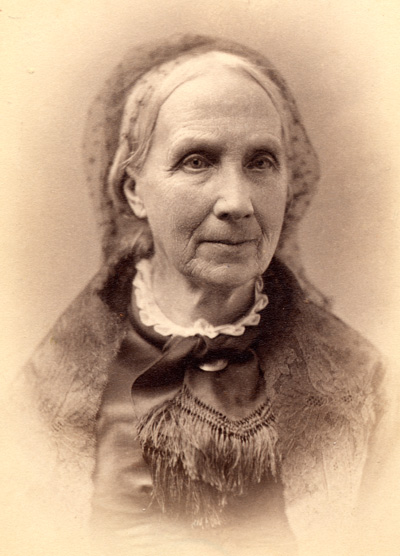

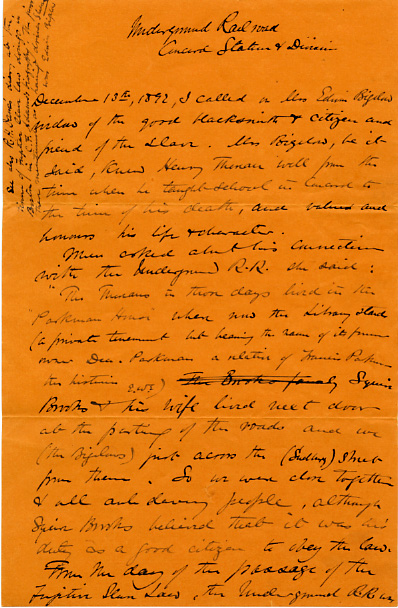

No other documented episode conveys the human drama of local involvement in the Underground Railroad so well as the story of the escape through Concord of Shadrach Minkins (also known as Fredric Jenkins, or Wilkins) early in the morning of February 16, 1851. Shadrach, a slave from Virginia working in Boston, was arrested and placed in custody in the Boston courthouse on February 1st , and rescued by concerted abolitionist effort on February 15th. Several surviving accounts by Ann Bigelow describe his passage through Concord. Although the particulars of the accounts vary, as a group they tell a relatively consistent story. Among the accounts are the earliest version published in 1877 by Harriet Robinson in "Warrington" Pen-Portraits,and Edward Waldo Emerson's notes from an 1892 interview with Mrs. Bigelow. (Edward Emerson's notes form part of a series of oral histories he conducted on aspects of the life of Henry Thoreau.)

|

|---|

|

|---|

|

|---|