Introductory note: This history is a slightly edited version of "A Brief Visual History of Concord," which was published in the Historic Resources Masterplan of Concord, Massachusetts (Concord: Concord Historical Commission, 2001), pages 13-22. It is included on the Library's Web site by permission of the Concord Historical Commission. The illustrations come from the Library's Special Collections and may not be reproduced in any form (including electronic) without permission from the Curator.

Contents:

From Glaciation to European Settlement

From Glaciation to European Settlement

Dirty ice from the Arctic to New Jersey, a mile thick over Concord, mashes and molds our land. Some 12 millennia ago the ice melts back in spurts. A glacial lake covers Concord Center. The ice drops its sandy gravels to form ridges such as Revolutionary and High School/Town Forest. Hills include egg-shaped drumlins such as Nashawatuc, Pine, and Poplar. Eskers in Estabrook Woods and the Country Club appear as curving sandy ridges. High flat areas south of Great Meadows, in Walden Woods, and south of Second Division Brook are gravelly outwash plains carrying icemelt away. Bedrock is exposed in spots, including Fairhaven and Farmer's cliffs, but lime deposits are rare.

Large chunks of ice are stuck in Walden, White, and Bateman's ponds. Smaller chunks lead to acid bogs, such as by Ripley School and the Old Rifle Range. Rollercoaster-like terrain scattered over town has pockets and pools called kettleholes, and knolls called kames. Fine sands and silts concentrate on the lake bottom, like the marsh by the High School. Tundra animals and plants, plus spruces, race in after icemelt. Vegetation creates a patchwork quilt of soil over the land. Wetlands remain as the glacial lake drains away. Short brooks, such as Jennie Dugan, Spencer, Mill, and Sawmill, plus subsurface flows, drain water from the land to rivers. The oft-swollen Assabet, Sudbury, and Concord rivers snake across the landscape. Bitter cold winds off ice and tundra to the north sweep Concord most of the year.

Humans arrive. About 12 to 8 millennia "Pioneers" (PaleoIndian/Early Archaic people) hunt in the sewage-treatment plant area, "the plains" around Barrett's Mill and Lowell roads, and near the Sudbury River south of Route 2. They share Concord with caribou and later-extinct species such as mastodons, the elephant's big cousin. White and jack pines invade. Over a few millennia the climate becomes warmer and drier than it is today. The cool evergreen forest is wiped out by oaks and pitch pines from the south, and various hardwoods and hemlock follow in moister sites. Deer, beaver, turkey, and a richness of deciduous forest animals accompany this Virginia-like vegetation.

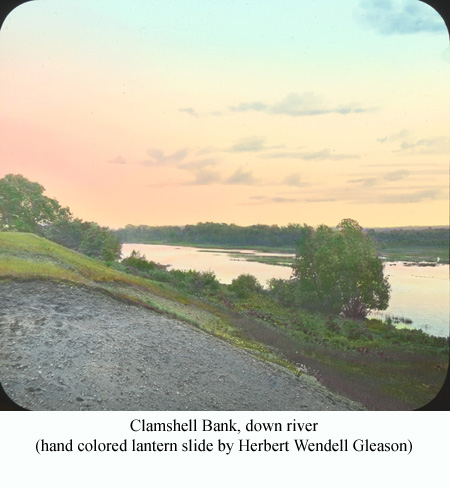

Between 8 and 1 millennia ago "Settlers" (Middle Archaic to Middle Woodland Hunters) of the Concord rivers walk every acre, every future Concordian's yard. Clamshell Bluff (Concord Shell Heap) under the Emerson Hospital parking lot is a seasonal camp, and a treasure chest for later archaeologists. Indeed, more than 16 camps flourish at various times, especially near brooks, rivers, and ponds across town. The Settlers collect fresh-water clams, make tools, cut with axes, hunt game with spears, grind food with stone pestles, and cook with soapstone pots. They eat plants, game, and fish, and even a current state-endangered turtle species. Settlers also move up and down the rivers bringing salt-water clams from the coast.

"Farmers" (Late Woodland) are in Concord between 1000 and 350 years ago. They move from summer on the coast to winter perhaps in Marlborough. Six seasonal farming camp areas are established from Bedford St. and Monument St. to the Country Club and Warner Pond. Overnight hunting camps are scattered all over town. Using brush and rocks, the people make weirs to catch fish in brooks. They plant corn, beans, and melons on Concord's scarce, valuable, well-drained, fertile agricultural soils. Wild rice in wet meadows, cranberries in bogs, and nuts in the woods ripen in autumn. These Farmers wear stone pendants, grind with pestles, collect firewood, cook with clay pots, cultivate crops with pointed sticks and hoes, cut trees, make dug-out canoes, and shoot game with bows and arrows.

What is Concord in 1635 when white settlers arrive? Ninety percent is forested. Floodplains and swamps support towering conifers. Oaks and chestnuts abound on hillsides. Dry sites are covered with sprouting oaks and somewhat-scrubby pitch pines. Open areas include tiny crop plots, regularly-flooded river meadows, and perhaps recent burns or hurricane blowdowns.

Nashawtuc Hill has a tiny native community, Musketaquid, of Algonquian people, probably just reduced in numbers by disease. Mill Brook in Concord Center has a fish weir. Trail networks cross Concord leading in all directions. Some relatively-open woods near Musketaquid result from long-term firewood gathering, wood cutting, crop planting, burning to clear fields, and escaped fires. With a drop in human population, game rapidly rebounds, as do sea-going and year-round fish numbers.

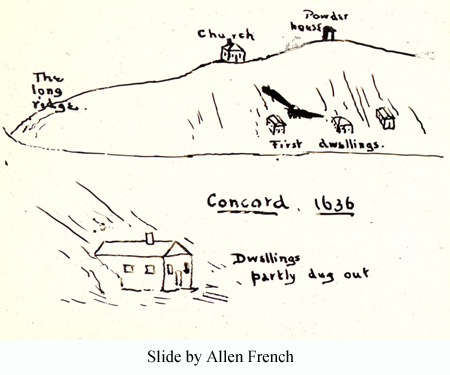

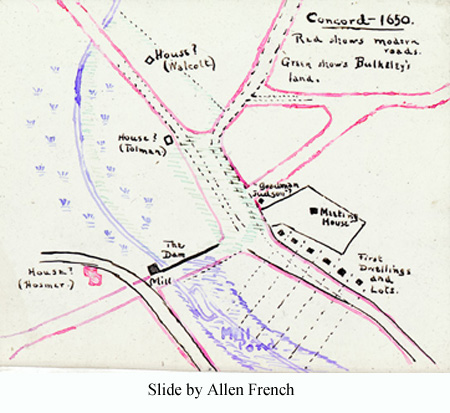

About a dozen English families establish Concord in a six-mile square purchased from the native population. This is the first official town in the interior of the Massachusetts Bay Colony above tidewater. Simon Willard, a land and fur-trade investor, and two Puritan ministers, Peter Bulkeley and John Jones, play key roles. Initial buildings, some apparently dug into the hillside, are put mainly on the south side of Revolutionary Ridge by Mill Brook. Why settle here? Probably the keys are an existing trail intersection, proximity to Boston and Cambridge, friendly native community, three rivers, warmth on the east-west ridge, dammable brook, good soils of former crop fields, and, especially, river-meadow hay to sustain livestock through the winter.

The settlers attempt to recreate an English village structure that includes land ownership, demarcated boundaries, solid buildings, wagon roads, mill dam, and pond. The Puritan meeting house on Revolutionary Ridge has no separation between church and state. The Hill Burying Ground is used. Around this settled nucleus is the commonland shared by all: river-meadows for hay, fields for cultivation, and forest for pasturage and hunting.

Beaver and other animals are trapped and furs traded. Native corn, beans, and squash are adopted for cultivation. The village grows eastward along Lexington Road. Roads are cut through to other early villages. Life in Concord is hard and some settlers leave for Connecticut, while others arrive from adjoining Cambridge and Watertown. Following a second division of land in 1655 and designation of town sections or "quarters," a building spurt of scattered farmsteads on good soils occurs. Commonland is replaced by large individual landholdings.

Wooden bridges replace fords. A linkage to Boston and England is maintained, and many household goods are imported. A school is built. Local industries for trade appear, such as smelting bog iron at the Damon Mill site. West Concord, with three waterways suitable for dams, has a scatter of homes. Small milldams, ponds, and mills for grinding grain, fulling cloth, and sawing logs appear on Spencer, Second Division, and other brooks.

Concord increasingly becomes a regional center. The town expands westward and northward.

The lack of seasonal migration by the Concord settlers puts ecological pressure on the land. Livestock spreads widely, grazing down the limited forage of the forest. Firewood demands for huge inefficient home-fireplaces clean out the understory. The forest is perforated and pushed back for wood products. Pitch pines and sprouting oaks decline, while maples, birch, beeches, red oaks, and white pines spread. Edge species and weeds from Europe explode across Concord. Local game and fish populations drop, and have no chance to rebound. Beaver doubtless disappears. Deer, turkey, wapiti (elk), moose, and wolf become locally rare or extinct.

The village is of "First Period" (Colonial or Post-medieval English) architecture. Houses are typically small, steep-roofed, 1 1/2- to 2-story structures, with huge oak timbers, a massive chimney, few tiny casement windows, sometimes a 2nd-floor overhang, and one or two rooms on each floor. Such forms are patterned after post-medieval English-village homes, and constructed almost entirely of local materials. Today about twenty Concord houses apparently incorporate small, 17th C. First-Period structures within their walls.

Some evidence suggests that three structures date to the 1650's, the Thomas Dane House (47 Lexington Rd.), Edward Bulkeley House (92 Sudbury Rd.) and Parkman Tavern (20 Powder Mill Rd.). Speculation continues that two rooms of the Old Block House (now at 57 Lowell Rd.) might have been the home of Rev. John Jones, a town founder and resident from 1635 to 1644.

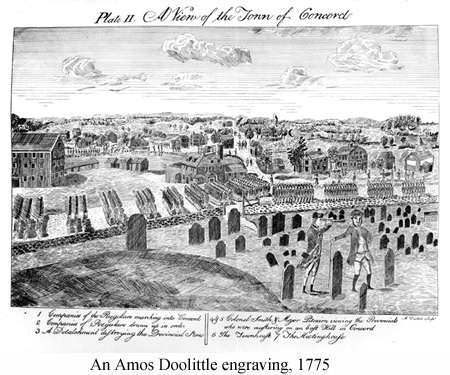

The town begins the 18th century 70% forested, and with sawmills buzzing. At the 1775 Revolution it is only about 30% forested, and 25% by century's end. Early in the 1700's the large trees are predominantly white and black oaks, with some hickory, chestnut, and pine present. Hunting continues and game is increasingly scarce. Many forest species become rare and some disappear. Cultivation, pastures, and wandering livestock cause erosion, sedimentation, and murky waterways.

Lexington and Weston replace Cambridge and Watertowne as neighbors, and parts of Bedford and Lincoln peel off from the original Concord land grant. Carlisle takes a large mid-century bite out of Concord, then disappears, and later reappears with an odd boundary that persists over a century. A giant network of stonewalls creeps over the land. By mid-century 200 farms cover Concord, with average farm size down to about 60 acres. Cattle, grain, and apple production predominates. Seeds of English hay and clover are imported, so some poor soils have better pasture. Productive soils and woodlot firewood are scarce. Subsistence farming is common .

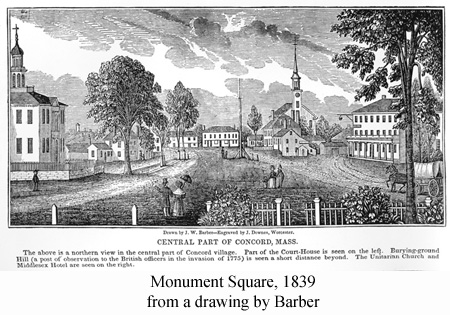

More roads are built. The town center is a busy crossroad and gathering place. Mills and home industries, such as blacksmiths, wheelwrights, and cabinet makers, spread widely. The town population reaches about 1550 (some 265 families) and stabilizes. Concord is politically moderate, but contains both loyalists and patriots, slavery and antislavery supporters. With few economic opportunities here many young people head elsewhere.

Just before 1775 the town becomes noticeable less tolerant of British rule. A Provincial Congress meets in First Parish Church. Arms and ammunitions are stockpiled. A spy gets a map of the town. British soldiers march from Boston. Revere, Prescott, and Dawes make a mid-night warning ride. At the North Bridge Minute Men from Concord and surrounding towns face men from afar.

Neighbors watch from the Old Manse. Musketballs fly. British soldiers retreat, with fateful skirmishes at Meriam's Corner and Bloody Angle. The six-year fight is on. Concordians continue to participate in making a new Commonwealth and a new Republic.

Concord's architecture blossoms in the 18th C. First-Period houses continue to be built until about 1725. A few retain portions of their original external form, such as the Old Ball House (Ball's Hill Rd.), Joseph Hosmer House (572 Main Street), John Melvin House (344 Westford Rd.), Samuel Fox House (505 Old Bedford Rd.), and Benjamin Barron House (245/249 Lexington Rd.).

Georgian (or Second) Period architecture of 1725-1780 is well represented today in Concord. Its high style is distinguished by houses two rooms deep, handsome cornices and decorative (often tooth -like dentil) moulding, prominent ornamented doorways, and relatively large sash windows, usually five-ranked and symmetrically aligned in the front façade. Many high-style Georgian buildings along Lexington Rd. are built by prominent citizens. Other examples are the Enos Fox House (550 Old Bedford Rd.), Edward Wheeler House (99 Sudbury Rd.), Charles Flint House (702 Lowell Rd.), and the house at 216 Westford Rd. The many Georgian farmhouses are a glory of Concord. Most have center chimneys, though the Old Manse (269 Monument St.) and Barrett House (612 Barrett's Mill Rd.) have two chimneys. The Wheeler/Harrington House (249 Harrington Ave.) and Samuel Buttrick House (1024 Monument St.) are built one room deep, whereas the Wood family houses (41 Wood St. and 631 Main St.) and Roger Brown House (1694 Main St.) are two rooms deep. The low English barns of the 18th C. with entries in the long side, such as at 320 Lowell Rd and 265 Ball's Hill Rd. are rare today.

Harvard College moves here briefly at the outbreak of the Revolution. From the Concord Fight to the end of the century, the number of dwellings only increases from about 190 to 225. A village (Hildreth Corner) develops in the Lowell Rd./Barrett's Mill Rd. area. Most houses built in Concord still use the Georgian style, such as the Thomas Hubbard House (342 Sudbury Rd.) and Jonathan Hildreth House (8 Barrett's Mill Rd.).

Federal Period (1780-1825) architecture develops slowly in Concord. This is distinguished by quiet elegance, a low-pitched roof with small cornices, often end chimneys, delicate graceful doorways topped with fanlights, large airy windows with little ornamentation, curved stairways, and simple artistic mantelpieces. The Stephen Barrett Farmhouse (107 Westford Rd.) is a scarce 18th C. Federal-Period home remaining. A courthouse and a 3-story granite jail are erected on the Green as public buildings, and later disappear.

Concord continues its 200-year deforestation process until by 1850 it is only about 10% forested. Except for forest around Second Division Brook and Walden Woods, the town is totally open with scattered woodlots. Much woodland is coppiced for firewood, with sprouts cut on 10-30 year intervals. Although oak-pine woods with red maple predominate, pitch pine stands are all over town. Grazed fields are pockmarked with pines.

The town's giant sponge, its forest, is largely gone. A downriver dam at Billerica, plus water releases from upriver reservoirs, raises river levels. The floodplain river meadows flood for long periods, decimating hay production. Industrial pollutants, and later sewage, transform the rivers. Firewood, charcoal, and water power form the energy base of society.

Stone walls, often with scattered white and other oaks, still dominate the landscape. Narrow walls are for pasture, and double-width for cultivation. Many swamps are drained for pasture, but with extensive erosion and sedimentation, farmland ditches must be dug out regularly. Farm size decreases and land is used intensively. Population grows to 2200 at mid-century, and more than doubles to 5700 at century end.

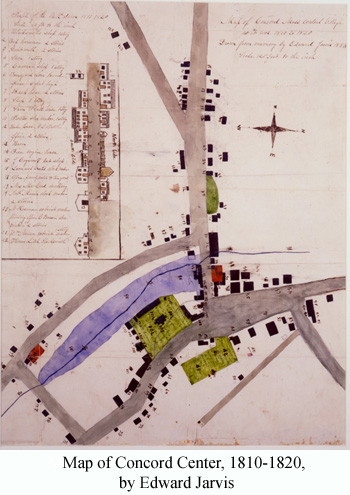

Big changes in Concord cascade through the 19th century. It is a bustling commercial center with a county courthouse and entrepreneurial spirit, at least through mid-century. The nearly two-century-old mill pond at the Center is drained, and the dam widened and covered with commercial structures (Map 5). Irish immigrants, and later, Canadian, Scandinavian, and Italian arrivals, enrich the town. Church and town separate. Religion diversifies to include Congregational, Unitarian, Universalist, Catholic, Episcopal, Methodist, and later, Union Church groups. Public schools are built in seven districts, and several private schools established. Coeducation and adult education both begin before mid-century. Influential authors, educators, and editors locate here.

Roads are added, including parts of Cambridge Turnpike, Elm St., Spencer Brook Rd., and Sudbury Rd. Damon Mill and other mills grow, making West Concord an industrial center. A Boston-to-Fitchburg railroad arrives in 1844, connecting Concord Center and West Concord to the wider world. Commuting and shipping products to Boston are faster; manufacturing expands. In 1850, 70% of the taxpayers are landless. A north-south Framingham-to-Lowell railroad and two other railroads create a rail junction. Coal becomes available, and efficient Rumford fireplaces and Franklin stoves decrease the amount of tree removal for fuel.

The state builds a prison, and Concord residents are actively involved in its operation. Three neighboring villages, Westvale (Damon Mill area), Concord Junction, and Reformatory, grow together forming a common sense of identity. Meanwhile taverns, hotels, and courts in Concord Center disappear. Manufacturing declines. And an amusement park transforms Thoreau's Walden Pond.

Crops diversify and production rises, taking advantage of new markets. Concord grapes are bred by Ephraim Bull. For a period, market-garden crops such as asparagus and strawberries cover the land, and dairying increases. Agricultural shows become a feature in town, though pastureland shrinks.

Meanwhile Concord becomes, some say, the literary capital of America. Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Louisa May Alcott, and Nathaniel Hawthorne are the best know of many thinkers and writers in Concord. Visitors from far-off places come to discuss major issues of the day. Transcendentalism develops, and the Concord School of Philosophy is built. Thoreau documents the town's natural history and geography, and briefly lives in a Walden Pond woodlot surrounded by intensive agriculture. Culture expands in academies, libraries, and lyceums. Voluntary associations proliferate. Women play major roles in town. Abolitionism is active and the underground railroad runs through Concord. Monuments in Monument Square and Sleepy Hollow Cemetery suggest the impact of the Civil War on Concord.

Dwellings in Concord increase to 255 by 1821, with many being true Federal style. Brick-ended residences are seen at the Samuel Hoar House (158 Main St.), Josiah Davis Double-House (204/206Main St.), and John Adams House (57 Lexington Rd.). The Edward Wright House (577 Monument St.) is a hipped-roof farmhouse, and the Tolman Shops (1 Lexington Rd.) a gambrel roof home. Farmhouses continue to exhibit a simpler vernacular mode than do houses in the town center.

Public, institutional and commercial building construction booms in the Federal Period. A public bathhouse, Trinitarian Church, several school houses, and a 5-story cotton mill in West Concord are examples. Of these only the Old Academy school building (25 Middle St.) remains. The Wheelock/Shepherd Tavern (122 Main St.) and a bakery (255 Lexington Rd.) are remaining Federal-era commercial structures.

Buildings of the Early Industrial Period (1825-1872) diversify to include several architectural styles. Greek Revival homes (low-pitched roof, cornice with wide divided band of trim, entry porch or portico with prominent columns, and long sidelights around door) include the Joel Britton House (310 Main St.), Ebenezer R. Hoar residence (194 Main St.) and Josiah Bartlett House (35 Lowell St.). Early Gothic Revival (steep roof, decorated boards in gables, pointed arched windows, and porch with flattened arches) is found in the Cyrus Pierce House (23 Lexington Rd.) and Simon Brown's River Cottage (49 Liberty St.). Second Empire style (mansard roof with dormer windows, and eaves normally with decorative brackets) is seen in the Lorenzo Eaton House (66/68 Monument St.) and at 44 Middle St.. The George Brooks House (1 Sudbury Rd.) is Italianate (two or three stories, low-pitched roof, wide overhanging eaves with decorative brackets, and tall narrow commonly-arched windows). Homes built during the Early Industrial Period are often relatively small, and many buildings are moved.

Fires destroy several buildings in Concord Center, and many institutional buildings are constructed near the Common. Schoolhouses rise on Stow St. Significant commercial buildings in the milldam area include a bank and insurance building (46/48 Main St.) and two attached blocks (23/25 and 29 Main St.). A brick Damon Mill is constructed in the Italianate style.

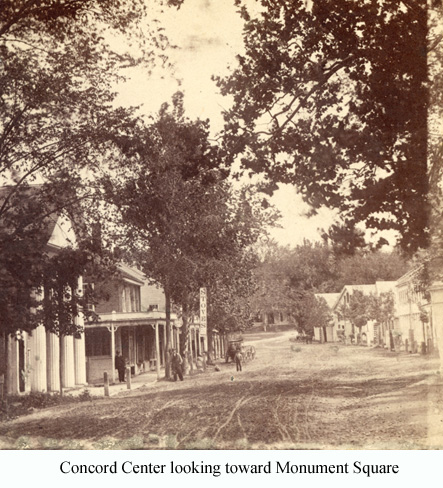

In the late 19th C. street construction accelerates and stone bridges span the rivers. Housing developments begin in earnest, such as on the side streets of West Concord, Hubbard St., Belknap and Elsinore streets, and Nashawtuc Hill. Large country houses spread along the Sudbury and Concord rivers. A Public Library, State Reformatory, and Centennial Revolutionary monument by Daniel Chester French appear.

In the Late Industrial Period (1876-1914) house styles diversify further, including Second Empire, Italianate, Stick, Queen Anne, and Colonial Revival. Second Empire "Mansard cottages" are built on Bow St., and Italianate homes on Hubbard St. and lower Elm St. Stick-Style houses (steep roof, decorative trusses at apex of gable, overhanging eaves, wooden walls often interrupted by raised horizontal and vertical boards) are built at 40 Elm St. and 63 Wood St. Queen Anne homes (steep roof of irregular shape, usually a long asymmetrical porch, and textured shingles commonly present on a wall) at the William Wheeler House (190 Nashawtuc Rd.), 339 and 349 Main St., and 625 and 648 Lowell Rd. Diverse styles of this period are also seen in the State Prison, Emerson School, Thoreau St. and West Concord depots, and the Gatehouse for the town's Nashawtuc reservoir. Blocks of buildings are constructed at 8-28 Main St. and 7-11 Walden St.

Four stone-arch bridges are built in the 1870's and 1880's: Elm St., Flint's Bridge (Monument St.), Nashawtuc Bridge, and Derby's Bridge (Main St.). A pipe system brings water from Lincoln, later distributed from the Nashawtuc reservoir, and still later replaced by Acton and Littleton water. Large gable-end New England barns of the late 19th C., representing Concord's agricultural heritage, stand out at 594 Strawberry Hill Rd. and 1487 Monument St. Carriage houses characteristic of town life remain along Hubbard St., and from 140 to 252 Main St.

The Centennial of the Revolution enhances the town's identity as a historic site. Memorials sprout around town. Tourists flock in. Village beautification accelerates, and the Ornamental Tree Society plants street trees.

As wood and farm products diminish in importance, land-use trends reverse. Pastures shrink, and woods expand onto stony sites to cover 40% of Concord by century's end. Red maple and gray birch colonize old pastures, although chestnuts become railroad ties. Concord's William Brewster, a leading American ornithologist, finds long-lost or scarce wildlife returning.

However, by the middle of the 19th C. Concord exceeds its carrying capacity. It becomes so densely populated, so dependent on imports, and with such an overused resource base, that its residents can no longer live sustainably on its 25-square-mile land. Concord goes from a relatively self-sufficient community supporting an economy mainly on its own resources, to a town highly dependent on outside resources.

20th Century

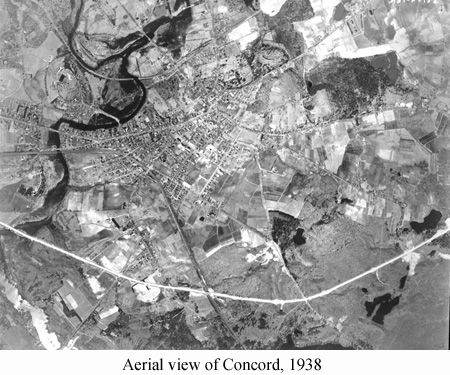

By 1940 open pastureland drops to 15%, and population grows to 8,000. Dikes create waterfowl marshes at Great Meadows. A 1938 hurricane flattens trees, especially in the spreading built-up areas. Pitch pine, long a premier tree of Concord's history, declines along with white oak. Disease decimates chestnut. Red maple, white pine, red oak, ash, and other trees take over, producing a forest very different from those at presettlement, revolutionary, or mid-19th-century times.

During the first four decades of the 20th C. suburbanization and city-commuting accelerate. Sewer and electric systems are built. Electric streetcars briefly zip through town along Bedford St., Main St., and Commonwealth Ave. Railroad lines decline. Wagons, horses, and walkers decrease, while automobiles and paved roads spread. Oil becomes plentiful, and auto repair shops emerge. Route 2 slices Concord in half.

Private schools, golf courses, and sportsmen's clubs appear on large acreages. A national wildlife refuge and state reservation protect chunks of land. Crops and dairying decline. Industrial mills decline. The area around Concord's railroad junction is named West Concord.

Housing developments appear southwest of Nashawtuc Hill, Between Lexington Rd. and Cambridge Turnpike, on Bedford St. and Old Bedford Rd., and along Main St. linking the east and west ends of town. Pine St. Crosses over the Assabet River. Homes fill land between Thoreau St. and the railroad, around Hillside Ave., and along Upland Rd. A lakeside cottage community with factory-built homes snuggles up to White Pond. During the Early Modern Period (1915-1941) the Colonial Revival style of architecture predominates, and many of the development homes are American Four-Squares, Dutch Colonials, and Cape Cod Cottages.

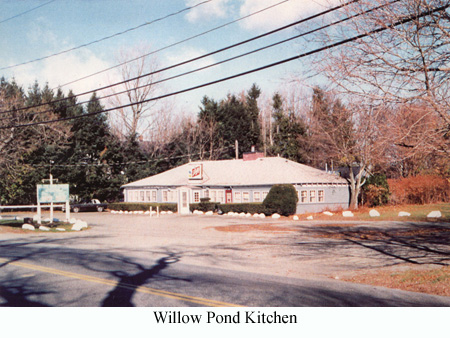

Among the impressive institutional buildings are the unusual Gothic-inspired Armory and the Spanish-Revival Harvey Wheeler School. Others are Colonial or Classical Revival styles, mostly in brick: Fowler Library, Concord Museum, Trinitarian Church, an expanded "Jeffersonian" Free Public Library, and Hunt Gymnasium. Commercial buildings in the Federal Revival style are visible at 59-73 and 747 Main St. Willow Pond Kitchen and Howard Johnson's (restaurant) are early road-houses to serve automobile travelers. And roadside farmstands are prominent features of this town.

To the outside world, Concord symbolizes devotion to liberty, intellectual freedom, and stubborn integrity of rural life. To most Concordians it is a semi-rural community of homes and neighbors. In 1940 residents sense war on the horizon. Yet they also look beyond it, and foresee aggressive planning, zoning, natural-resource protection, and historic-resource preservation as keystones to Concord's future.