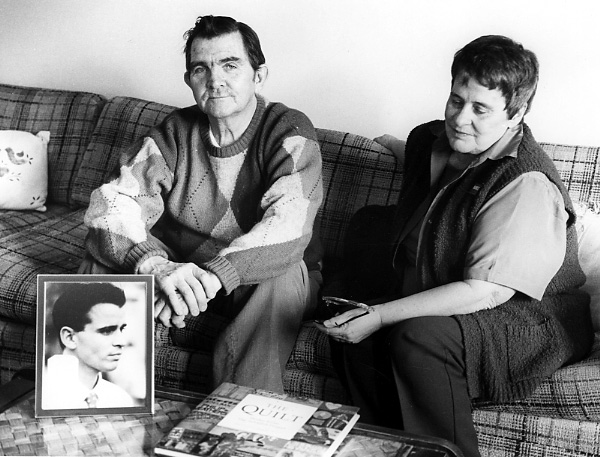

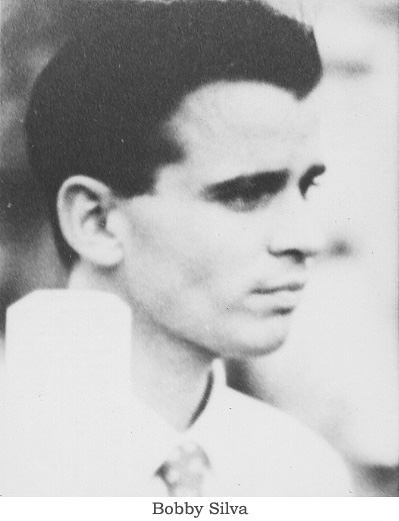

Mary and Joe Silva

A Death in the Family from AIDS

32 Bradford Street

Interviewed January 19, 1990

Concord Oral History Program

Renee Garrelick, Interviewer

Transcription sponsored by Beacon Communications, Acton, Mass.

Mary and Joe Silva lost their son Robert to AIDS

on November 10, 1987. The Silvas share their

experience as a family coping and supporting

their son during the last 10 months of his life.

Mary and Joe Silva lost their son Robert to AIDS

on November 10, 1987. The Silvas share their

experience as a family coping and supporting

their son during the last 10 months of his life.

They address the loneliness of the disease, particularly if it means revealing homosexuality to their families, the excruciating pain and suffering of the patient, the reaction of individuals outside the immediate family, and their own family's subsequent involvement in AIDS related activities, such as the quilt project and hospice following Bobby's death.

Mary and Joe Silva lost a son Bobby to AIDS on November 10, 1987. During the decade of the 1980s, we as a nation learned about AIDS and the devastating loss it has taken in our country. The Silvas will be sharing their experience as a family, losing a son, but also having him close with them during the last ten months of his life as he was dying from this very painful disease.

Can you tell me what it meant for Bobby to be here at home both for him and for the

family members?

Mary -- It's a lonely disease and at least when he was here he

had all the family coming in at different times, people around

him loving him. He could talk when he wanted to, he could mix in.

He saw all his nieces and nephews. He had moments when he would

be alone and think about dying and it's scary. At least with his

family around we could ease that a little bit for him.

Joe -- The biggest part of the whole thing is being alone, people not knowing, the fear of what they are getting into or what they are dealing with. Knowing that someone loves you and you have someone there when you need them because you have to be scared in this situation. It's a great thing that his family was so close.

During the time that he was here family members naturally had to cope with the expense

of someone so ill. Family members then pitched in?

Mary -- Expense was not discussed at all, everyone just

automatically picked up something and did something. It was

nothing that we said, you do this Kathy, Joey, John, Mike,

everyone just did it. If anyone was here and a prescription

needed to be filled, Michael usually took care of his prescriptions down at the drugstore. They all picked up a

different area and nobody even knew what the other was doing half

the time.

Bobby was one of six children. Kathy is the oldest, and we had the five boys after Kathy. Bobby is the next to the youngest and Danny is the youngest. Bobby was very close to Danny and they were close to the end. Dan was in the service at the time when Bobby was home and he could call home from Korea when Bobby was real bad. He stayed nights in his hospital room in Boston. Two members of the family at a time were always with him.

Joe -- Dan went down one day to the 5 & 10 and he came back and he had a few packages of jingle bells and he had some fishing line and he had some eye hooks. I didn't know what he was doing and he started putting them up and he strung the fish line through here and the bunch of bells out here. Well, then in Bob's room he put a tie down from the fishing line so that it was right next to Bob and if we were out here watching TV and Bob was sleeping and he woke up and needed something or someone because he couldn't get out of bed at the time, he would just pull the tie and the bells would ring and I thought that was great.

Bobby had an apartment in Boston where he stayed and worked but he'd come home and stay for a few days. We'd nourish him and get him built up again and then he'd go back because you've got to be with your own friends. But you've also got to be with your family at times. At this stage of this disease everybody was scared of it and didn't know what they were dealing with, and it was great to walk in the house and know that you were welcome just like any other member of the family.

You had oxygen and other equipment here?

Mary -- Right from the start we had oxygen and equipment here.

He also had an oxygen pack that he could carry. If we would go

for a walk, we would just put the pack on him and we'd walk up the

street and around the neighborhood. We kept decreasing how far we

could go but it got him fresh air.

He was at the Deaconess Hospital in January when we got the call from Dr. Rose and he was in almost six weeks then. That was his longest stay. Then he came home with us and he stayed with us until the end, but every once in a while he would go back to Boston. We worried when he went back there because they wouldn't eat right.

So the disease has its remission, its ups and downs?

Mary -- The disease takes all forms. Bobby had pneumoconiosis

pneumonia and he was prone to the pneumonia part of it. Others

have different things that attack the body.

Joe -- He would get a cold and that cold would automatically turn into pneumonia, there was no controlling it. He had very strong medication here, cough medicine which was very strong, and he did get on the AZT but then he told me one day that he was going to get off the AZT. It make him sick and very nauseous.

Mary -- I was asking the doctor for AZT. It was hard to come by. It was hard to get. I practically begged Dr. Rose, at least then you knew you were fighting with something, but Bob said he didn't want it, he saw so many people get sick from the side effects of AZT so I had said to him "How about if you try it? Try it for a month, two months, three months and then if you decide you don't want it, I won't demand that you take it." So he said "okay". And he took it for about 8-9 weeks but he got anemic, we had to take him in for blood transfusions from the AZT. Some people can take it and it never bothers them. Bobby just couldn't handle it. He said he didn't want to take it any more. He said "I'd rather be able to do things in my last months and be happy then be laying in bed sick."

I didn't want him to stop it because I thought if you stay on it long enough it's going to work. You know how you want it to work, almost demanding that it work on him. But I wouldn't think of making him take it.

Joe -- At the same time you've got to stop and think that they know what was going to happen and they have no cure for this.

Mary -- We started talking about Christmas and I said we should jump in the car and go and pick out a few little things. And he says "Mom, I'm not going to be here for Christmas. I'm almost positive I'm not going to be here for Christmas." And I said "Bobby, it's all in your head, think positive." It was surprising how we did fool so much. We used to laugh about it yet it wasn't anything to laugh about but I think it relieved the tension that we all knew and yet he was able to talk about dying. He even told me that he didn't want a funeral, and I said let's be reasonable, let's talk about it. So we even discussed his funeral. After a discussion like that I would go out for a walk by myself and I'd cry.

It's a very painful disease?

Joe -- It's a very painful disease. You have to be very

careful when you change their beds, touch any part of their legs

or any part of their body and it is excruciating pain. So you

have to be very careful how you handle them. This is why hospice

is so good, they know how to handle these people. They've had

experience before whether it's AIDS or it's cancer or anything

else, they know what they are doing and they were a great help to

us.

At first we didn't know the hospice program was at Emerson Hospital but when we did find out, people were right here when we needed them. They got us medication that we would have had to go into Boston to get through Bobby's doctor, which would have been hard but we got it through Dr. Purcell's office here in Concord and they were very helpful. Maureen Bannon of the hospice program was very helpful, she told us any time day or night they would be here.

And you did need them?

Joe -- We did need them. We needed morphine desperately and we

gave her a call and she got us morphine and syringes which we kept

right here to give Bob a shot when he needed it. He only had two

shots. Maureen gave him the first shot and Michael gave him the

second. This was the day he died. When family members like your grandchildren came to visit, were there any special

precautions you had to take in associating with an AIDS patient?

Mary -- I told my children in regard to the grandchildren coming to visit to call their own doctors and the doctors told them they didn't have to worry about it. The grandchildren, they are all small children, would come in and run in the bedroom and they used to draw pictures to hang on his wall. Every day someone would be coming in with pictures to hang on his wall. They jumped all over the bed. They'd sit beside him and talk to him.

Joe -- Before he got real sick, he would come out and sit and watch TV with me or he would go lay at the foot of his mother's bed and watch TV and talk to us. The thing was he had somebody.

Mary -- We never took special precautions for anything.

Joe -- The only thing was bodily fluids.

Mary -- I would expect anybody to do that because I wouldn't take a chance with any of my other children or grandchildren.

Joe -- There was never a concern with us from the time we went to Deaconess. I remember one time he had to put on a mask, I was taking him for a walk in a wheelchair, and the nurse said "Wait a minute, put a mask on." And he got insulted. And she said "Well, the mask is to keep you from catching cold or anything from anybody else." So he said all right and we used to go for walks in the hospital.

When did you find out that Bobby had AIDS?

Mary -- He was diagnosed in June 1986 and we didn't find out

until January 1987. He said he tried to tell us many, many times,

that's when he was coming home and he had a cough and I kept

asking him to see somebody about that cough. He would say he was

taking something, then he told me it was allergies, then he told

me it was asthma, he didn't want to tell us. He knew his father

had a bad heart for years and he didn't want to upset him and he

didn't want to upset me. He was a very tender, loving person.

Joe -- It was a great relief when we did find out because then he relaxed more himself.

Mary -- I said to him, "Bobby, you never had to worry about us. You could have said it anytime to relieve yourself." What fear that must be in their minds to know something like this and not be able to talk to people about it. I said, "Did you think that we wouldn't be with you?" He said, "No, I was never worried about that. It was I couldn't stand hurting you." He said to me many times, when we would be talking if I was in his room or he was in mine, and he'd always say, "Watch Dad very close when I die. Take care of him."

At the wake that was held in this apartment members of the homosexual community in Boston who were his friends mingled very easily with people here.

Joe -- And people knew that they were gay people and they sat around here and they were like they were cousins. Nobody took any precautions, it was just one big group saying goodbye to Bob. It was wonderful.

Did he speak to you about his homosexual friends?

Mary -- He did speak to us about his homosexual friends.

Terry his friend lived here with us for a while. He was with him

several years and he stayed here quite often with us. Toward the

end I think Terry got upset and couldn't handle it and he stayed

in Boston.

I asked Bob when he knew he was gay or how did it come to him. He said he knew he was different at 10,11,12,13 years old but he didn't know why, he didn't understand why. It wasn't until he was in high school that he started realizing that he was gay. He did talk to Kathy about it in later years. And Joey found out about it. I think Joey just realized it. When Bobby moved to Florida, Bobby told me this, Joey didn't, Joey wrote him a letter and said, "Bob, I realize you're gay and it makes no difference to me and I'm sure you don't have to stay in Florida if you would rather live in Concord. Give your family a chance, come home, tell them, you don't have to live in Florida, you don't have to live in Boston, you don't have to live any place unless you really want to." And he did come back home about a month after that. He told me he treasured that letter and he saved it. And I asked him, "But did you know it anyways that we would always stand behind you. We've always said no matter what family is family." He said he did know but he was so afraid of hurting.

It's a dual struggle, they are struggling with the disease and they are struggling with announcing they are gay.

Joe -- The main thing is to have people accept them for who they are.

Mary -- It's a hard thing. You can just be in a group and there's always someone that will make a remark about gay people or a joke about AIDS but Bobby said you learn to accept it. You learn to live with it.

When you first saw him so sick at the Deaconess, you felt the family rallying and visiting

made so much of a difference in his recovery.

Joe -- They called us from Deaconess in January 1987 because

they thought he wasn't going to make the night. He was very bad,

he was barely breathing, and he couldn't really talk and be

conscious. He'd go in and out of a semi-coma, the whole family

got down there and he seemed to know they were there.

Mary -- Bobby had called first and said he was in the hospital. I said we would be right down. He didn't want us to come down then because it was at night and he didn't want us to drive he said come tomorrow. Then Dr. Rose called and he said to please, come down and see your son tonight. I asked the doctor what was wrong and he said, "I can't tell you, your son will talk you." He was very tender on the phone. Joe and I walked down to the fire station and told Michael, and Michael had to be replaced down there and I went to the bank and got some money. Michael called Johnny and Johnny came back here and we went down to Boston. We stood at the bed and the doctor had told Bobby that he had to tell us that he had AIDS. Bobby was trying to get it out and I put my arms around him and said, "That's okay, I understand. You have AIDS and you don't have to talk and you're gay and we don't care." You could almost see the relief in his face. When one of the others asked, Bobby said "Ask Mom, she knows." It was like a total relief that someone else was there.

They called Kathy at the Cape and Joey came down from Vermont, then the Red Cross and the Army were trying to contact Danny. The doctors said he wouldn't live the night or until Danny got home. In fact, one of my sons asked me if I wanted him to call any of my sisters or brothers and I said, "No, he's going to get better and we're going to take him home." He says, "Mom, you don't understand, this is really bad and we may not be taking Bobby home." I said, "We're going to take him home. And we did." Finally a couple of days later they picked up Danny at the airport. Danny was in the Army stationed in Korea. Kathy and I were in with Bobby at the time and they came back from the airport and Danny walked into the room and walked up to Bobby and said, "Hi, Bro!" Bobby looked up and had a big grin, he still had all his masks and everything on. He put his arms around him. It was amazing, Bobby's breathing got better within the next hour, the nurse brought in ice cream and tonic for all of us. We were sitting around the bed.

They were great to us. They always put a cot there because like I say there were two members of the family there 24 hours a day. We'd get our meals and eat with Bobby. We had plants and Valentines around the room. He came home before Valentine's Day but he says "Watch out for Mom, she'll decorate the place."

And this was in contrast to so many others you saw at the hospital who suffered alone.

Joe -- So many others had no visitors at all. They would be

laying there totally alone. The nurses would take care of them.

Some of them had to be fed. That's the hard part about this whole

disease.

Mary -- It's a lonesome disease. I think anything even if you have cancer just knowing that you're going to die must be an awful feeling. These people were left alone.

We didn't know how the disease was going to go. We did not know what to expect from one month to the other. I thought that once he got over the pneumonia, he was going to be fine. But it attacks all different parts of the body.

Mary -- Bobby would say, "The only reason Mom wants me home is because she has a chance to cook all this stuff, she thinks she's got a whole gang here again." Sometimes we used to cook four or five different things because the taste buds go. He couldn't eat some things.

Everything starting popping up. Now we understand AIDS, then we didn't. We didn't know which way we were going.

One very beautiful way that you have kept his memory alive is involvement in the quilt

project. Could you explain that'?

Mary -- This fellow in California started the quilt project in

remembrance of a loved one. I heard it about even before I knew

Bobby had AIDS but I didn't pay that much attention to it. Kathy

had said to me after Bobby died, "Mom, why don't you make a

quilt?" And I said no, I didn't think so. I decided to make it

and just couldn't sew. I totally went blank on it. A couple days

later I got up at 5:00 in the morning, got the material out and

started on the designs. We went all over looking for a cat

because of his baby, he had a cat he loved. Once I got into it,

it made me feel so much better because I was doing something.

This was only a couple of months after Bob died. I was doing

something and I think it was healthy, actually.

What are some of the other symbols?

Mary -- The flowers are all the nieces and nephews and the

rose, Bobby always gave his sister and the girls a rose for their

birthdays or sent them roses. The message is "Love is forever."

That was the year the calendars came out with the "Love is

forever" message so I ordered seven or eight of them and gave them

to the children for Christmas.

We went to Boston with the quilt and we didn't know what to expect. They came here to pick up the quilt for us and we gave a picture of Bobby and we had to write a letter describing Bobby, what he liked and what he didn't like. When we went to Boston, it was amazing. We were totally amazed at all the people at The Castle, hundreds and hundreds of people and it was totally quiet. That's when it really hit you, not just your son, but all these people who have died from this disease.

Joe -- You could hear a pin drop. All these people were looking at all the quilts all over the walls.

Mary -- Then we went to Washington D.C. in 1988 and 1989. In 1988 I was a volunteer and at 5:00 in the morning I helped lay out the quilt all over the ellipse and went to the training. With the training we had, in a minute and a half, if it rained, we could fold that quilt up and have it wrapped. Again it was doing something. For two days they read all the names of every person that had died of AIDS, and John and I had the honor of reading off a list of names, and I was able to say Robert Joseph Silva, our son.

I felt so proud that day. My sister Sheila and Kathleen and Peter and all their families were just getting on the field when it happened that I was on the podium saying names, and Peter turned around to his kids and said, "God, that sounds like my sister." And Kathleen ran up and said, "It's Mary up there doing her thing." Like he said it was amazing that they got there right then. My whole family was right there together.

Now your son Joe has become involved in the hospice program.

Mary -- Yes, he started the training right after Bobby died and

he goes to Boston for meetings from Vermont every month or so.

When we had the mass for Bob, Joey took me out in the kitchen and

he showed me that he had completed his program on November 10, a

year to the day that Bobby had died. He helps patients with AIDS

or without, he just is involved in caring.

Joe -- He's executive director of the humane society in Bennington, Vermont.

How did other people react?

Joe -- Most people reacted very well especially close friends.

Nobody seemed to talk too much about it but they accepted it. The

fear of not knowing is what turns people off. You go to the

hospital to have something done and they explain to you what they are going to do, that this is going to hurt or that you're going

to get this shot, and you know this and accept it. But with AIDS

it's the fear, people didn't understand it and a lot still don't

understand it and it scares them so they are afraid to deal with

people who have AIDS. The hard part is education, to get people

educated about AIDS. The only things you have to worry about is

bodily functions or blood or needles, like the drug addicts that

pass their needles and everything else and that's how a lot of

them get AIDS. The fear of not knowing is what scares people.

They have to know that these people are sick just as though

they're cancer patients or multiple sclerosis patients or anything

else. They are dying from a disease that nobody really

understands and someday there will hopefully be a cure.

Mary -- I think it is devastating any time to lose a child. You don't expect it. We don't expect to be here and Bobby not.

When people would come, would they be afraid to drink out your cups?

Mary -- We did have that with some people. It hurt very much,

but I do have to understand because fear does a bad thing to all

of us. People didn't want to sit down and have a meal or drink

from our cups or use our silverware.

Joe -- There weren't that many people but again you have to understand the fear. They don't understand it. Once they understand something, fine, then they can accept it. This is a hard thing. There was panic when this came out. People dying of AIDS. Everybody was panicked about the situation but once you got to know you can live with somebody like Bobby, you get to understand it and then you've got to think about them. It's got to be mind boggling to know you're going to die and not know when and live with this day by day. This is why they need somebody.

Mary -- And see all their friends die. He'd get a phone call when he was here and he'd come out and I would ask. "What's the matter, honey?" and he would say so and so died. You'd see the tears in his eyes. Terry and Larry would come in and get him dressed up to go to a funeral. You want to protect them, you don't want them to go someplace where you know they are going to hurt, but of course, they have to go. They would take him to a funeral in Boston of another friend, another friend. I still see it. Terry still visits with us quite frequently and Larry calls us.

Do they have AIDS?

Joe -- No. A lot of them won't be checked out now because they

don't want to know. If there was a cure then they would take a

chance to be checked out and take the cure but right now there is

no cure so a lot of them back off from getting tested because they

don't want to know this for certain. They must know by their

health, they don't feel good at times, but at the same time they

back off from this because they don't want to know. So it's got

to be a real sad situation for a lot of people.