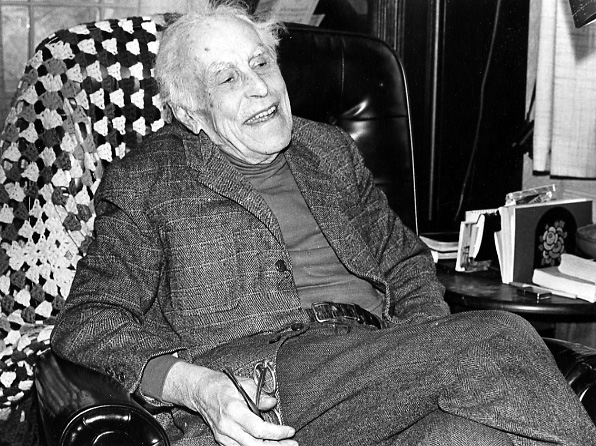

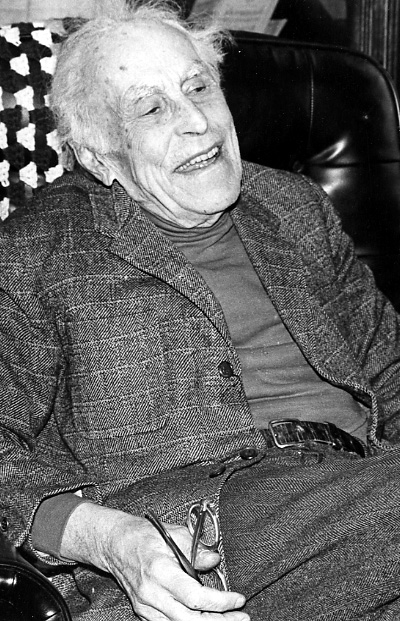

Laurence Eaton Richardson

363 Barrett's Mill Road

Age 84

Interviewed January 19, 1978

Concord Oral History Program

Renee Garrelick, Interviewer.

At the turn of the century Concord was a real country town which could be divided into three sections: (1) the residential village, fairly compact between the two depots, the stores on the milldam in the middle; (2) the farms surrounding the village; and (3) the industrial sections and the Reformatory at West Concord (hereafter referred to as Concord Junction, as it was then named), which had its own stores near its own depot, and its houses more or less grouped around each manufacturing establishment, and the Reformatory. The general impression was that of a band of woodlands all around the town boundaries especially on the heights of land toward Carlisle, Acton and Lincoln, inside of which were broad meadows and open farm lands with here and there a house with a big barn and sheds. The maple swamps, or the fields with alder, cherry or juniper, which we see now near the former farms, were kept cleared and used for pasture, or cultivated. Often in well-grown woods today, the regular marks of old furrows can still be seen. The meadows, too, along the larger brooks and the rivers were clear of brush and trees for they were mowed each summer and had been for two hundred years for their hay. In this farming area stone walls crisscrossed the fields everywhere except in the meadows, and bordered the country roads. Even where stones were not immediately available, they had been brought from nearby, for it was the cheapest way to fence pastures and mark boundaries.

At the turn of the century Concord was a real country town which could be divided into three sections: (1) the residential village, fairly compact between the two depots, the stores on the milldam in the middle; (2) the farms surrounding the village; and (3) the industrial sections and the Reformatory at West Concord (hereafter referred to as Concord Junction, as it was then named), which had its own stores near its own depot, and its houses more or less grouped around each manufacturing establishment, and the Reformatory. The general impression was that of a band of woodlands all around the town boundaries especially on the heights of land toward Carlisle, Acton and Lincoln, inside of which were broad meadows and open farm lands with here and there a house with a big barn and sheds. The maple swamps, or the fields with alder, cherry or juniper, which we see now near the former farms, were kept cleared and used for pasture, or cultivated. Often in well-grown woods today, the regular marks of old furrows can still be seen. The meadows, too, along the larger brooks and the rivers were clear of brush and trees for they were mowed each summer and had been for two hundred years for their hay. In this farming area stone walls crisscrossed the fields everywhere except in the meadows, and bordered the country roads. Even where stones were not immediately available, they had been brought from nearby, for it was the cheapest way to fence pastures and mark boundaries.

Nowhere do I know of a place in Concord bounded as in the eastern part of Bedford by ditches a foot or more deep, dug in the 17th Century through the woods and fields for miles, and, surprisingly enough, still to be seen. The typical farm comprised about 100 acres of cultivated land and pasture with the necessary woodlot often not adjacent, but away toward the edge of the town. Even families in the village often had their woodlots situated in the remoter sections of the Estabrook district near Carlisle, near Annursnack, over by the airport, in the Walden-Fairhaven district, or in the Powder Mill woods which kept the old name of the 2nd division.

Inside of the band of farms was the village - compact yet not crowded. There were no large open areas between houses, each house seemed to have been built one step farther out from the center and the last one might be the first farm, or part of it, perhaps a mile out, often less. For example, on Sudbury Road, Dr. Robinson's was Caleb Wheeler's farmhouse with the big barn on the corner of Thoreau Street, although the railroad when it came had pierced through, leaving the fields up Sudbury Road somewhat cut off. On Monument Street, the house beyond the railroad crossing belonged to the Prescott farm which stretched diagonally across to Bedford Street. The river, on the north and west bounded the residential districts.

Throughout the residential area, and beyond in some cases, there were smooth gravel sidewalks wide enough for at least two to walk abreast, except where the tree trunks projected into them. The trees were glorious. They had excellent care and had not been butchered to provide room for electric light wires nor yet begun to suffer by the amputation of their roots by the laying of water and sewer pipes. Neither were they deprived by solid street pavement of half their food and water supply as well as support. Only the canker worm had so far attacked the elms. Some of the elms were so big they nearly blocked the sidewalk. One, I remember especially, on Main Street, about at the Children's Shop and another on Lexington Road near Heywood, and then there was the very large one in front of the Town Hall which projected well into the street and was surrounded with seats for the weary - or those just waiting.

Between the sidewalks and the street was a strip of grass two to three feet wide cared for by the abutter with as much attention as he gave to his lawn, and on the other side of the walk usually a fence of wood or iron, rails or pickets, and always as well or better painted than the house. In front of each gate was a block of granite 6-8 inches high, to make the step into the carriage easier, and one or often two stone hitching posts or a plain wooden post maybe with an iron cap to keep the horses from eating it.

The buildings on the Milldam would look today about as they did then if you tore down those built since. Only Friends' Block containing the Concord Clothing Company, the Drug Store and Miss Buck's, the Nell Ann's of 1900, occupied the west corner on Main Street. From there to Sudbury Road were small houses which appeared much as those today. In place of the Savings Bank across the street, there stood, well back from the street, a good sized white house, part of which was said to be the old block house of King Philip's War, and behind it was "Barrett's Spring" which, according to the newspaper when it was closed that year, "Has supplied the thirsty for more than 200 years." The rest of the north side of Main Street remains about the same except for Colton's which was a big wooden grocery store and most of the sidewalk was covered with a roof. The stores on the south are about the same too, but some had covered sidewalks and there were a few trees. I particularly remember a good sized elm in front of the drug store. Around the corner on Walden Street was the Post Office, a few small shops and a sort of tenement where the Concord Fruit Company is. Beyond was a large barn where hay, grain and coal etc. was sold and then the livery stables, now the Ford Agency. Across Walden Street where Woolworth's is, stood a nice old house somewhat run down and since moved back and made over for furniture storage.

At this time, the population, not counting those confined in the Reformatory, was 4,792, a gain of 25% in ten years. This was fast growth and it was beginning to change the town. Going by the nationality of the father, the pupils in the schools in 1900 were 409 American, 375 Irish, 110 English or Canadians (mostly from Nova Scotia), 74 Scandinavians, 25 French Canadians, 8 Italians, 17 scattering. The total was 1,019, so by pointing off one place you get the approximate per cent for each group. However, Concord Junction figures are included, which distorts the picture as far as the Concord Village is concerned. I would guess that without the Concord Junction figures the population was about 50% American, 35% Irish, 8% Nova Scotian, and 7% Scandinavian. Except for Concord Junction and the influx of Italians as labor the town was growing mostly by the gradual settlement here of Boston businessmen who acquired farms and established large estates. There were many Concordians commuting to Boston, too, and it seemed as though a large population of these were lawyers. The South District court was at Cambridge so Concord was not an inconvenient place for a county lawyer to live, halfway between the two courts [Lowell and Cambridge] and with good trains going to each. Boston was equally convenient.

Also, there were people who came to Concord to live who did not commute. Writers, artists, sculptors, naturalists and others not businessmen or lawyers, who were attracted by the natural beauty, the good transportation available and perhaps by the Emerson-Alcott tradition, possibly with a touch of Dan French. Walton Ricketson was a sculptor, some of his work now is in the Library, and there were several others. The Emerson-Alcott tradition that I mentioned was very strong in town. Emerson was remembered with veneration and affection by all of the older generation. I recently read of an incident which although it took place years ago when he was still alive, expresses what to me was the feeling the townspeople still had regarding Emerson. "Mrs. Hoar, seeing a neighbor who came in to work for her, drying her hands and rolling down her sleeves one afternoon, somewhat earlier than usual, asked her if she was going so soon. 'Yes, I've got to go now. I'm going to Mr. Emerson's lecture,' was the reply. 'Do you understand Mr. Emerson?' Mrs. Hoar inquired. 'Not a word,' was the answer, 'but I like to go and see him stand up there and look as if he thought everyone was as good as he was.'"

Thoreau was a street, a cove of Walden Pond and a famous nature writer. There must have been few in the town who thought of him as a political, economic or philosophical thinker. Generally, I think the grandparents who knew him hoped that their grandchildren would not grow up to be like him, and although "Walden", the "Week" and the others were read with interest it was because we were swimming in Walden and canoeing and camping on the river.

To get to the industrial part of the town we must go west on Main Street, cross the Sudbury River, turn across the railroad tracks (there was no bridge then) and pass the two farm houses that had been there a hundred and fifty years or more. Beyond, there was a mile of fields and woods until we reach another group of farmhouses near the Assabet River. It was almost like going to another community. Today when Concord and West Concord are nearly together and getting so intermixed that newcomers soon, I think, will come to recognize no dividing line, it is not so easy to recall that in 1900 it was, in all but town government, a separate entity. Forty years before 1900 there was no Concord Junction. The Derby farmhouse and barns were nearly alone where they are now across from the fire station; near the outlet of Warners Pond were the few buildings of the Lead Works and a mile farther out Main Street, where it crosses the Assabet, were a few houses around the Damon Cotton Factory. This changed after the Framingham and Lowell R.R. was built crossing the Fitchburg as its successor the New Haven does now. Soon another railroad, the Concord and Montreal, was extended from Nashua through Dunstable and Westford to Concord Junction, and the Middlesex Central was extended from Bedford to the Reformatory when that was erected. The Reformatory land had previously been the State Muster Grounds. With its establishment in 1878, first for a short time as the State Prison, the houses around it were built, and also a considerable number across Elm Street between the River and Barrett's Mill Road. These houses also served the railroad employees for this was a terminal with a round-house for the locomotive and other facilities. The depot was a large building of three floors, the two upper being a hotel with the dining room sharing the ground floor with the waiting room and ticket office.

Similarly the rest of Concord Junction grew by the addition of the employees of the three railroads there. Concord Junction was first called Warnersville for a Mr. Warner of Arlington who ran a pail factory on the site of the Lead Works. This burned to the ground about 1900 and was not rebuilt, manufacturing having ceased some years before. Mr. Harvey Wheeler and others started the Harness Shop and built houses for some of the 150 employed there on Crest and Cottage Streets. Besides the Cotton and Woolen, or Worsted Mill at Damondale, then called Westvale, with its own separate Post Office, there was also a Rubber Shoe Factory of some importance, but in some ways the most important industry was a little Bluine factory which gave premiums of dolls and toys to children selling their product. They advertised each Sunday in the comic sections of the newspapers and did such a big business through the Post Office that Concord Junction was a 2nd class office with letter carriers years before Concord. Altogether Concord Junction seemed to be a coming industrial center when, this year, the American Woolen Company purchased the land along the river including what is now General Radio and extending to Elm Street opposite Howard Johnson's; and started construction, at least to the extent of unloading building material, engines and boilers. The company also took an option on forty acres on Barrett's Mill Road to include the mills, the pond and the field opposite to the river. The excitement in Concord reached fever pitch but influential directors called a special meeting and persuaded the others that the Merrimack would carry off the waste better than the Assabet so the boilers and all were put back on the cars and shipped to Lawrence to be erected there. The result was the famous Wood Mills. So Concord Junction settled back as it was with its small industries and the Reformatory. The principal association with Concord was in the High School which children from all over town attended.

The high standing of the schools of Concord at that time was exceeded only by that of the schools of Quincy. There was a grammar school at the Junction, one at Concord, the Emerson school and the High School beside it on Stow Street. Our teachers were of the best; those in the High School mainly all graduates of Wellesley, Smith, Mt. Holyoke or Radcliffe and they stayed so long that they knew whole families, having taught them all from the oldest to the youngest and sometimes the parents as well. The school committee report for 1900 however laments the fact that there were fewer and fewer teachers who had been here for a term of over 20 years. The pay of all teachers ranged from $200 to $500 per annum and they were of the town or boarded with some family and were in every way a part of the community. For example two grammar school teachers boarded with Miss Ellen Emerson for many many years, and their classes had a party each year at the Emerson's where they had the freedom of the house to play games and later had refreshments. Some children did not finish high school but a majority did and many went on to college. In this particular year three went to Harvard, three to Brown, three to Williams and one to Tech. A. Finnegan was a prize scholar at Boston College. The appropriation by the Town for the schools that year was $25,000 including transportation which was provided by five horse drawn barges for grammar school children who lived more than a mile away. The others walked or rode bicycles. No provision was made for transporting children to High School and I read in the paper that someone counted sixty bicycles outside the door one day. Others got rides in by horse and buggy and those from the Junction came by the steam cars as did those, not mentioned before, who came from Boxboro, Lincoln and Bedford. A few came from Acton and a few years later all came, and from Carlisle as well. Altogether the High School had 224 pupils. There was one private school for boys, the Concord Home School on Wood Street, but the pupils all came from away. It was taken over that year from Mr. Garland, who had started it, by Mr. Eckfeldt to be run somewhat on the lines of a church school. He moved on to establish St. Andrews a few years later on Punkatasset Hill and by that time Middlesex had been started so there were soon three private schools for boys. For girls and boys under 10, there was Miss White's on Belknap Street with six or eight boarders and perhaps twenty pupils in all.

I spoke of the High School pupils from Concord Junction coming to school on the steam cars, but by the end of the year there was an alternative. The electric cars came to town. First the line from Lexington pushed up through Bedford to Monument Square and a few months later a line from Hudson came down to meet it. Now a special car was run for the High School pupils from the Junction but they paid their own fare. The network of electric railways extended all over southern New England and it was a treat to ride on them, at least in summer. One went to Salem or Marblehead for the day, people could commute to Lowell, Reading, Marlboro and Hudson.

I haven't mentioned the other methods of transportation that existed and were really the more important - the horse and the steam railroad. If you didn't live near the stores you needed a horse for transportation of supplies, but then of course, you were on a farm and had one or more anyway; however, there were two large livery stables centrally located for those without horses. Horses were used for travel to nearby towns and for pleasant outings too. This item from the Concord Patriot gives you an idea. "George Cabot Lodge and his bride were guests of the Bedford House, Monday afternoon. The young couple drove into town in a carriage drawn by a white horse. They had tea at the hotel and early in the evening drove on to Concord." Hardly a house on Main Street but had a stable, and most are standing today either as a garage or a separate dwelling. And in every stable cellar was one or two pigs. Just a few years before, the Board of Health wrote in the Annual Town report. "The matter of keeping swine, in the village gives the Board more trouble and bother than anything else."

But the railroads were the backbone of the transportation system. It was easy to get anywhere. Nineteen trains left for Boston on the Fitchburg R.R., the best taking 32 minutes. From seven to nine o'clock in the morning there was one about every fifteen minutes and of course they returned at night the same way. People living on Monument Street or Lowell Road scorned them however, for they could amble over to the depot on Lang Street, sure to get their regular seat, as the train started only two miles away at the Reformatory. They had seven trains a day in and out of Boston which also connected at Bedford with trains for Lowell, Nashua, Manchester and Concord, N.H.. From Concord Junction, besides these same twenty-six trains each way, there were two for Nashua and three for Lowell and in the other direction three from Framingham and thence to New Bedford, Providence, Springfield or New York, especially New York, for the afternoon train ran right to the side of the Fall River boat. The railroad employees were an important group in the town and you would little guess today how important a man the Station Agent was in town affairs. In 1896, both the one at Concord Junction and the one at Concord were on the school committee and each later served as a selectman of the town for several years.

There was plenty of subdued social activity in town for young and old; likewise recreation. There were the five churches about as today with their usual societies for various good purposes. There were eight or ten mutual benefit societies or lodges, the Grand Army of the Republic was still very important, and the Concord Antiquarian Society was very active as its publications show. Five or more clubs took care of the spare evenings. The Social Circle, the Tuesday Club and the Ladies Tuesday Club met each Tuesday, the Concord Saturday Club, the last Saturday of each month, the Concord Choral Club Monday evenings, and not connected with any church, The Union Bible Society and the Concord Female Charitable Society. Many of you, members of this society although now under another name, may not recall its stated object, "To help the poor and needy of the Town, to feed the hungry and clothe the naked". If this wasn't enough activity there was "a literary and social club for the residents of Monument Street only", meeting Monday evenings during the winter months.

On the lighter side, there was the B.C. and W. Club; billards, chess and whist, "for social intercourse and recreation" with rooms above the Drug Store in Friends Block, open both day and evening. Another club was trying to keep the river from being invaded by undesirable elements from outside. The Concord Canoe Club was formed "to keep control of certain points bordering on the river; to prevent their sale, or use by objectionable people from camps etc., and thus shut off Concord people from them". Once a year the club had an all-day picnic with canoe races and water sports, first at Fairhaven Bay and later at the new club house just below the Old North Bridge, usually on July 4th, and in the evening a "Carnival of Boats" in which each boat or canoe was lighted with Japanese lanterns, and the occupants dressed and posed to represent some idea or object such as "Liberty" or the "Minuteman" much as in street parade floats today. This "Carnival of Boats" had been given up by 1900, but I remember one revival about that time. The procession started from above the railroad bridge on the Sudbury River and ended below Monument Street on the Concord. I don't know how many floats there were but from where I was, it extended from Nashawtuc Bridge up around the bend of the river to Elm Street. The Water Sports continued several years and consisted of Ladies' Canoe Race, Men and Boys' Swimming races, a tub race, and tilting, among others. Besides the canoes of people along the banks, the causeway and the North Bridge served as a grandstand for those who could not get on the big club piazza.

Altogether the river was a recreation area, a social center and a street. In summer four or five well-known swimming holes attracted the boys, people of all ages took their picnic suppers to their favorite places summer evenings, and during the day canoed up or down the river for miles. Nearly every house on the north side of Main Street had a boat house for several canoes and the shore outside was lined with those of their friends, neighbors, or relatives. The boys went on overnight camping trips as far as Saxonville or Billerica and the girls went with them on house parties, well chaperoned, at the various camps that could be rented. A week at Staples Camp on Fairhaven Bay for a party of eight boys and six young ladies plus a chaperone was a social item in the weekly paper. There were two or three steam launches that puffed sedately up and down carrying ten or more people, but they were too much work to use often. In the winter the river provided skating for all, long trips when it had been very cold and the ice was safe, but almost everyday on the meadows except when snow interfered. Because the meadows were mowed each summer there were acres of clear ice, enough for skate sailing when there was a wind.

Also in the winter there was plenty of coasting on Nashawtuc with double runners or bobsleds holding six or seven, and of course sleigh rides and evening pung rides often to the Wayside Inn for supper. Skiing was beginning to be popular here, perhaps one of the first towns in the east to enjoy this sport. It consisted mostly of jumping but skis were also used to travel along the roads. This custom was introduced by the many Norwegians in town, one of whom made skis to sell in the one progressive sporting goods store in Boston that saw the possibilities of this sport.

But to get back to summer swimming. When the river was too low and warm to be refreshing we went to Walden. Sandy Beach, near the road, required bathing suits, but Thoreau's Cove and Sam Hoar's point nearby were free country and all you needed was a bicycle to spend a happy day there. The south end of Walden near the railroad was still a summer picnic ground for Boston groups. It started as a place for social meetings of Sunday Schools, church festivals, temperance meetings, spiritualistic encampments etc. There was a railroad station and the grounds were furnished with seats, swings, dining hall, dance hall, bath houses, boats and fields for sports. The race track is still indicated in the woods south of the railroad. By 1900 however, the place was less popular. However, the paper reports "Tuesday there was a picnic at Walden at which the members of six colored churches were present. It is said that the grounds were literally black with people." The Chinese had a big outing there too that year, all dressed in native costumes which certainly astonished one Concordian who came upon a group of them wandering through the woods near Fairhaven Bay.

Tennis and golf were available. I think there was but one tennis court, maintained by Mr. Hudson on a lot he owned on Devens Street. The Golf Club had started in 1895. The nine-hole course was west of Nashawtuc Hill, between Muster- field Road and the old railroad track, and produced several good players. I think this was one of the years that Miss Grace Keyes won the Ladies State Championship and the Club team played the Country Club and the few other clubs that were in existence. Murray Baldwin made the best scores, but George Keyes was the club champion, and he also played in the tennis tournament in Newport that year.

Dances were held in the Town Hall, now the Town House, which for such occasions was entered from the rear. Up a broad staircase half way to the second floor, the stairs divided - right for the men, left for the ladies - leading to their respective cloak rooms. The dance floor covered almost all the rest of the building though near the dressing rooms, was a platform and on the side of the Square a small hallway at the top of the main staircase. A large balcony covered part of the floor and the hallway. On the ground floor was a kitchen, a small hall and the town's few offices, seldom used. Town business was done at the respective officer's house or store. Dances were usually sponsored by groups of young people. In addition, certain larger organizations gave dances which were publicly advertised, in the hope of making money for some cause. Different from these were the sociables given by Miss Ellen Emerson who put a notice in the newspapers that she was having one of her square dances. Twenty-five cents per family was charged but people contributed when the hat was passed, if there was a deficit. Miss Ellen was a distinguished person in town and did things as she wanted, not conventionally. It happened that my sister was born on her birthday and until she married and moved away, Miss Ellen sent a pint of cream from her own cow for a birthday present each year.

The hall was also used for public meetings and the Lyceum Course every Wednesday night during the winter. The speakers were not as prominent as those fifty years before but it was generally educational and the younger people of the town were always encouraged by their parents to go. A report in the paper tells of the fourth number in the course which was on Egypt. "It was illustrated by good slides, some of which were colored to show the exquisite tints of nature and the costumes of that people." The Concord Dramatic Club also used the hall for their performances which rated highly. They should, for not only did we have Allen French, but Henry D. Coolidge, clerk of the State Senate, and most interested in producing and writing plays. That year he had two produced professionally in Boston, one at the Castle Square and the other at the Bowdoin Square theatres.

Besides the Town Hall, the other buildings around the square were about as now. Monument Hall, was not there but the Middlesex Hotel built in 1844 stood in ruins where the Honor Roll now stands. It dominated the corner, three and a half stories high, a two storied portico on Main Street, and a low covered piazza its whole length on Lowell Road. It had not been occupied for thirty years and was an unsightly wreck resented by the populace who in Town Meeting appointed a committee to get it removed. This they did by buying it themselves, tearing it down, and at the next meeting proposed that the town take the land for a park. Their report illustrated what I previously said about open spaces. "Your committee believes that any taxpayer who, recalling the appearance of our common thirteen months ago, looks on that smooth lot and open view across the meadow to Nashawtuc and the sunset sky beyond, will not reject the course recommended by the committee."

The Wright Tavern had been reopened a few years back, after having been used as a private dwelling with shops in the ell for a hundred years previously. This was promoted as an attraction for tourists and prospered for a few years.

Speaking of tourists, the town was full of them on foot and in carriages. First they came by train to the depots but as soon as the electric cars reached town they poured into the village every half hour to the extent of an estimated 12,000 that year. The carriages from the livery stables met each car and the guides stormed aboard so furiously to solicit customers that the selectmen had to have red lines painted on the street, beyond which they could not go, to enable the regular passengers to descend and depart in peace. Just as it did a year or two ago, the tourist problem troubled the town committees. The Board of Health in 1901 reports "Our next largest expense was in maintaining the sanitary in the rear of the Town Hall. This work at the sanitary was more than doubled owing to the influx of visitors to the town who came on the trolley cars. This sanitary is a crude affair at the best and we have decided to abolish it and would call attention of the Town's people to the fact that some better arrangement with running water should be provided for the 'strangers within our gates' as well as for ourselves."

The holidays which were the occasion of public observance were April 19th, Memorial Day, July 4th, and Labor Day. The celebration of the 19th was larger than usual in 1900, the 125th anniversary, with Charles Joseph Buonapart, the orator, at the exercises. He was a distinguished attorney from Baltimore and later Secretary of the Navy and Attorney General in Theodore Roosevelt's cabinet. Memorial Day, called Decoration Day then, was in general much like ours but the whole day was much more reverent and everyone attended the services. Fourth of July was not like ours. One was awakened before daylight by the boys of the neighborhood with fire crackers up to 6 inches long and as loud as a shot gun. Besides this racket it was a morning for Antiques and Horribles parades and the finding and replacement of gates, chains, signs, garbage pails or anything the youth of the town had removed the night before. Later in the morning, there was a clay pigeon shoot and a baseball game between the bachelors and the benedicts. Labor Day the Knights of Columbus took over with their big field day at the Cattle Show grounds at the end of Belknap Street. The building of the Middlesex Agricultural Society still stood for dining and dancing in the evening. During the day, besides baseball, midway, balloon ascension and parachute drop, the harness races drew the most interest. There was a half mile track and pacers and trotters came from all around to compete for the $100 prize in each race. There were also bicycle races, for bicycles were in their heyday. On all these holidays and pleasant Sundays during the summer, the bicycle clubs from around Boston swarmed the roads in groups of 50-100. The riders, dressed in brightly colored striped jerseys which were as loud as their cries, rode noisily through the town. The one policeman on duty tried hard to control them, and reported that year four arrests for speeding, that is - riding a bicycle over 10 miles per hour.

Another bad traffic situation on certain days in the spring and fall was caused by herds of cows. Much of Boston's milk supply was produced locally in Somerville, Roxbury, Cambridge and other nearby towns. Dry animals were sent out to the summer mountain pastures to freshen. An early morning start brought them through Concord before noon, herded by boys and old fashioned Shepherd dogs and they passed up Lexington Road, Main and Elm Streets on their way to Mason, Temple or even Jaffrey. Needless to say every one came out not only to watch but to keep the tired and hungry animals from turning into gates and driveways to tempting lawns and gardens. Concord farmers also made milk not only for local needs, but for Boston. There were 1,252 cows counted in 1900. A milk car was side tracked at the depot each night and filled in the early morning to be picked up by the scheduled train about 8:30. The milk for local consumption came from farms on the edge of the village, but many families had their own cow.

The main crops of the farmers however, were hay, strawberries and asparagus. Quantities of hay were consumed by all the animals on the farms. Strawberries were a profitable cash crop, and all the land that held its moisture through June was used for strawberries, while the sandy fields for miles around were covered with asparagus. This was the big crop. Concord raised more asparagus than any other town in the country and "Concord Grass" was a standard of excellence. The first commercial farming under glass had been started by the Wheelers at Nine Acre Corner and another activity was the Stock Farms or Boarding Stables such as those on Simon Willard Road and Baker Avenue, besides several others farther out.

But agricultural activity began to decline from about this period. Other important changes were taking place. The electric cars had arrived, and now the streets were being dug up for a municipal sewer system. Town water had been available by gravity from Sandy Pond for twenty years, but with increased use, the cesspool situation was getting troublesome. There were no septic tanks then, all the waste going to an underground reservoir which had to be pumped out by hand at least once a year and carted away in a very smelly wagon. The town discussed a sewer system and in the discussion it developed that as long as it was necessary to have a power plant to pump waste to the filter beds, a dynamo at the same plant could be installed at reasonable additional expense to supply electricity at least for street lighting. The plan was approved and numbers of Italian laborers began to dig, with picks and shovels, narrow ditches 10-15 feet deep in some places. A power house was built where the present Road Department buildings are now, two dynamos installed and poles erected for street lights and wires. Before this the streets were lighted by oil lamps which were attended by two lamp- lighters who made their rounds in the late afternoon with horse and wagon. The year's supply of kerosene purchased from the Jenney Manufacturing Company cost $381.00 according to the town treasurer's report.

With the prospect of electricity near, those along the way began having their houses wired for interior lighting, for one of the unpleasant chores of housework was the daily collection of the various lamps, to refill with oil, trim the wicks and wash the glass chimneys. Consequently, there was a demand for electricians, and several competing contractors busied themselves getting the houses ready for electric lights. Prescott Keyes was the only one to be ready in February when the system went into operation, and his was the first house to be lighted, and for a few days the wonder of the town.