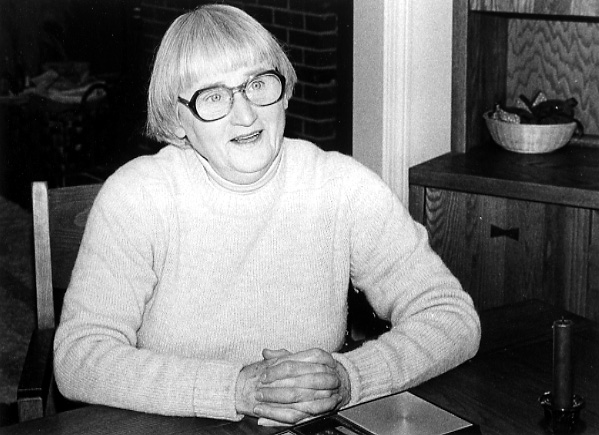

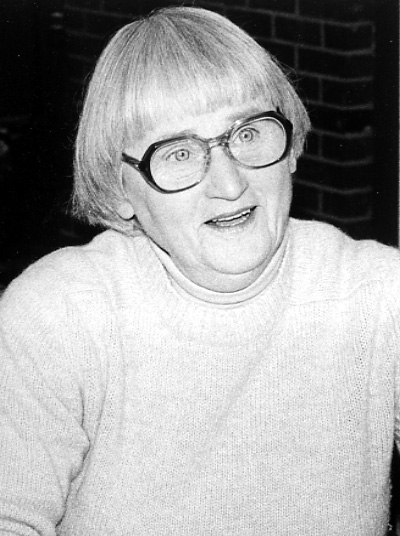

Helen (Reddy) Root Kent

Intervale Farm

82 Sandy Pond Road

Age: 65

Interviewed January 11, 1982

Concord Oral History Program

Interviewed by Renee Garrelick

(Abridged transcript)

The Concord Players

The Concord Players

Life on Intervale Farm

It seems to me I was born with an interest in local theatrical productions (The Concord Players). All the time I was a little person my mother and my father and my uncle Ripley (Daniel Ripley Gage) were involved in The Players and I got so used to people learning lines around the house or making costumes around my house or leaving to go to rehearsals or to build a set or take the set apart, that I just thought it was a part of everyday life. As a matter of fact, I always felt that everybody grew up and was a Concord Player.

It wasn't a bit surprising to me when Uncle Ripley would say to me, "Well, Hed, do you want to go down to the hall and strike the set?" It is now 51 Walden but Uncle always called it "the hall" and so did Hans Miller and so did Sam Merwin and so did Mr. Sager and Marvin Taylor and Phil Davis and all the old Concord Players from the '20s and the '30s.

I went down with Unc the first time when I was about nine years old, I don't know exactly what it was, to strike a set which was the most marvelous thing to me. It was a double level set with stairs running up the back of the set so you could pretend to be upstairs and open the upstairs windows and look down onto a little green and a fish pond and all kind of things like that. I thought that was absolutely magic. I hated it when the men took it all apart. It wasn't really real life but it was a magic life that you could do in your spare time and have a good time about it and was one good way to relax and to use your imagination.

When I was about fourteen, it was 1932 and it was the year that the Players did "Little Women" for the first time. It was Hans Miller who started us wanting to do "Little Women." Every ten years he wanted us to do it. And my mother Olive Root was on the costume committee. And my father, George F. Root, whistled "the robin" because they needed somebody who could do bird calls. They needed a robin when Beth died, a very poignant scene. And my Uncle Ripley was playing Mr. Lawrence, the rich man next door. And my sister and I, because we were teenagers, were ushers, my sister Anne Root McGrath, who is the curator of the Thoreau Lyceum. She lives on Barrett's Mill Road now; she used to live on Sandy Pond Road with us. The only person in our immediate family who wasn't connected with "Little Women" was my sister Pete who was four years younger than I, and was really too young to have any connection with it at all.

My house was always full of costumes. I went to a few rehearsals and fell madly in love with Carolyn Farnsworth who was playing Jo, and I vowed that in ten years I would be twenty-four and I was going to play Jo. That was the only thing in my whole life for the next ten years. I was going to play Jo the next time!

In the meantime I met and actually physically talked to my greatest heroine of all in the theater -- Katherine Hepburn. She had a summer place near my cousin in Saybrook Point, Connecticut. I actually met her and her two sisters. My younger sister, Pete, and I played with her younger sisters one summer when I was thirteen or fourteen. And of course, she played in "Little Women" just after we did. It is still the best movie of "Little Women" there is. The later ones weren't anywhere near as good, or as true to the script. And, of course, that reinforced me. I was just absolutely going to play Jo. Then, of course, came the war and we couldn't do "Little Women" in 1942.

So the next time it came up, I was going to be thirty-four, and that was going to be just too old to play it because as they did it more and more, they realized that they really ought to have younger people. The cast of 1932 was really pretty grown up to play "Little Women," but it was typical of the theater that children didn't play the important roles unless it actually called for a kid. I think it's better with teen-age kids or very early twenties playing it. Caroline Farnsworth had two children at the time she was playing it, and the little boy was just tiny at the time, and she had to keep taking time out to take care of him in rehearsals. That really didn't matter because she was marvelous as Jo, but I like to have the kids younger. The performance we did in 1962 had really young people in it; and in '72 as well. They had a lot more of what you're used to now as the spirit of the theater. The '32 performance was very technically theater of that day. And they were very good. And it certainly made an impression. But I liked the lightness of the later performances a little bit better.

In '52 my kid sister was sick. She had a fatal illness and she was sick for a long, long time. And I couldn't be away from her for very long. So I couldn't have a really busy part in it, much as I wanted to. And Father decided he didn't want to do "the robin" again, twenty years later. So, at least I could do that. I used to go down about 9:30 every night and whistle "the robin" and then come home again and take care of my sister.

Then in 1962, I played Hannah, much to my joy. Ray Baldwin and Joan Baldwin directed the play in 1962. I think they had in 1952 as well. They did it again, and I actually got to play Hannah which was lovely because now I was too old to play Jo and I was too busy as well. And I had a lovely time playing Hannah. I don't think I was very good, but I can just remember Granny Buttrick -- that's Mrs. Stedman Buttrick, Sr. -- from Liberty Street. She played it in 1932, and I always loved Granny Buttrick any time she was on the stage. Her very good speaking voice and way of speech always turned to an Irish brogue. There was nothing you could do; no part Granny ever did on the stage was anything but an Irish brogue and it was marvelous. She was supposed to be a native of Concord and just an old Yankee lady, but I can never forget Granny's performance of it.

Now, in '72, Vinnie McCloud was the director of it. Mary Niebold, who is now dead, and I were the producers of it. Producing is a terrible job, because people are getting hold of you from all over the world, literally, to get tickets and to find out how long the run is going to be. And they'd start way back when they know it's the turn of the year.

I enjoyed set design, but I'm better, really, at set dressings and props. I love to do props, particularly in a musical show. You see, I was brought up in the kind of theater where you had a whole box set, and sometimes even a ceiling that came down. And the curtain closed between either scenes or acts, and then everybody scurried around backstage and took all that scenery down, sometimes there would be a dozen men backstage, all tearing around and taking the set down.

And twenty years or so ago, they didn't have any curtain that closed. You did it with the lights. The lights would go out and people in black would sneak around and change things, and you didn't have all solid pieces of scenery that were set. That's the kind of thing I love to do. I love to be all in black, especially in musicals when it all goes very fast.

I was the producer of the very first musical show that The Players did. That was "Kiss Me Kate" in 1960. That was my first producing job, and I was the one who had been yelling the most loudly about The Players doing a musical. We'd never done a Broadway musical. And I was reinforced like mad by Pat Butcher who also wanted to do a musical, and by Dave Edgar from Concord. He was very up in arms about it. He wanted to do it so much that he got to be musical director of it. That was my first introduction to shifting a sixteen-set musical production with an orchestra and everything. It was the first time I had had a stage manager on one side, an assistant stage manager on the other side, connected by head phones; and they were connected to the light box, and everybody was in communication together.

When I was nineteen, and it was 1936, and I was absolutely determined to go to a summer theater and be an apprentice. And back in 1936, those were pretty "schnitzy" days to go off by yourself if you were a small-town girl and be an apprentice in a summer theater. I wanted to go down to the Cape where Henry Fonda and Margaret Sullivan were, at the Falmouth Playhouse. And Richard Aldrich and Gertrude Lawrence were at the Dennis Playhouse. I wanted terribly much to be that kind of a person, to be introduced to the theater that way, and to get a chance to go to Broadway and all kind of things like that.

What I learned at the end of that theater was that I was not going to be the greatest actress in the world. I just plain wasn't an actress, but I was always going to love the theater. I was going to learn a tremendous technical amount. That's how I wound up backstage, rather than on stage.

When I came back from that theater that summer in 1936, I was nineteen years old. I was going to be twenty in October, and I was put on the Executive Board of The Concord Players which was being next to God in those days because The Players was not a great open thing with everybody giving suggestions in those days. Plays were cast, for instance, on the telephone. You didn't go and have days and days and days of casting. The first play that I was in was "Mr. Pym Passes By", probably the biggest money-loser The Players have ever had, the smallest audiences, and the least interest.

I didn't really have very many parts in The Players. I wasn't really an actress. I loved being connected with the shows, though. Hans Miller directed a melodrama in ... I don't know what year ... I was twenty or twenty-one so it was '38 or '39. It was "Silas, the Chore Boy" which was lovely. I had the leading part in that. I played Silas, the chore boy. I had my front teeth blacked out, you know, and that was great. And there was all kind of tomfoolery in that. We had a big cast in that and Hans had a marvelous time. I think he played the villain as well as directing it.

But the one that was the hardest of all was the Chekov's "Three Sisters". Vinny McCloud and Tom Ruggles were the producers of that show. We'd never done a Chekov before, certainly not since I was connected with The Players. But they decided not only would they do a Chekov play, but they would do it in the round. They had three levels of stage out in the round, and therefore three levels of audience to be able to look over all the stages. The bedroom was up on one level; the dining room and sitting room were on one level; and the garden, which was the sitting room in one part, and the garden in the third act, were on the floor level, and the audience was backed up against the stage and against the wall toward the bank and then at the front of the theater, diagonally across the front of the theater. It was incredible. And Tom's awful job was that he had to get the auditorium back into use for the band rehearsals once a week, no matter how we had it all set up, and we had performances with the audience all around, and all the seats set up for all the audience. Tom had to take down the end of this theater where the band stage was so that they could practice. Then he had to put it all back again for the rehearsal in the middle of the week and the performances at the end of the week. And he and a whole crew did that for the three weeks of the show, and the week before as well because of the dress rehearsals. That was awful because you had a whole houseful of furniture and you had to have it Victorian, but you had to be able to see the people on the stage from all sides. You think of big, heavy Victorian furniture and you can't get it so that you can see through it at all the stages.

Then the food, I think, was probably the most difficult thing because the audience, right on the side where the dining room was with the banquet set for thirteen people was less than six feet away from the audience. The people who were sitting at that table were practically in the laps of the people in the audience. And they could see what you were eating, or not eating, so we had real food.

And we had real crystal glasses. And we borrowed a lot of glasses from the caterer so that they came in trays that were all marked off in rows, and each glass had its own separate place. That's how we kept from breaking them because we had real crystal goblets. Oh, the responsibility was terrible, really wild.

We figured at one time that backstage we must have had over five thousand dollars worth of things that we had borrowed from people that were really fine and valuable. That was really a great responsibility.

I think I can tell you what it was like growing up on the Intervale Farm. In the first place, my father was not born to be a farmer. My father was born into a very musical family in the city, in Chicago, Illinois, and he really didn't know how an old New England farmer actually was, but he loved it so that he turned himself from one kind of life into a completely different kind of person, and got to be a real old Yankee farmer before he was through. But it wasn't born into him.

I think the feeling of the farm was born into the three of us girls, who grew up there, very much. The farm was far enough out of town so that we didn't have neighbors running in and out. We had no radio until I was about twelve. Our first car we got when I was about ten. We had a Model T when I was ten. Then we had a radio. And then television, of course, didn't come until the fifties.

But we three girls learned to play by ourselves and with one little girl from the neighborhood almost exclusively. We made up our own games. We three went to the Concord Academy, and the little neighbor girl went to the regular public school, and she was my staunch ally when I switched in the sixth grade to the public school.

But things like noises, and smells, and sounds ... my father used to whistle. He was very musical; he sang very well. He was a concert singer, actually. He had an older brother who was in light opera. He used to tell us stories of the musical life in Chicago. We really grew up on father's stories a lot because we didn't have television; and they were so much more valuable, except, of course, it's very small and just family. Pa used to tell stories wonder- fully. He could be very, very funny or he could punctuate a story with songs. As a matter of fact, his conversation used to be quotes from plays and songs, and poetry too. He'd come in, for instance, on a day when everything had been going wrong, and he was feeling tired and dejected, and he would say, "The years like great black oxen tread the earth, and I am scarred beneath their passing feet." He was half funny, and half serious. But the quotes and the songs that he would use depended on how he felt that day.

And there was another thing which my sister Anne always quotes. Father used to love to read Henry Thoreau. Of course, Intervale Farm was Edmund Hosmer's farm at one time. But in one of Thoreau's books, Henry says, "I stopped on the south side of Edmund Hosmer's barn and had a conversation with Edmund Hosmer on a cold February day and it was warm on the south side of the barn." And I grew up knowing what it felt like on a cold February day to be on the south side of that barn. Father used to say at the breakfast table on a nice day, as we all sat down to breakfast, "Now, on a day like this, Henry would say ...". And we grew up thinking that Henry was perhaps some member of the family that we never saw. We always wondered if he was going to come. Father would always call him Henry and would quote him all the time.

Mother was a Montessori school teacher and also a dancing teacher. She and her sister, my aunt Alice, had a dancing school. They used to go up to Middlesex School, for instance, in the days when Mr. Windsor was the headmaster, and dance with the boys, and they would be the only girls there because it was not allowed to have girls at Middlesex School, but the boys needed to learn how to dance, so mother and auntie would dance all afternoon with one boy after another, trying to teach them how to dance. And she taught us to dance when we were very little, and I started teaching dancing when I was about fifteen.

I had private dancing lessons which I would give for the grand sum of two dollars an hour. All the boys who had grown up and gone through the Concord schools and refused to go to dancing school but then got to be the age when they wanted to go to a dance and dance with the girls didn't know how to dance, so I'd give them a crash course just before the sociable when they got to be thirteen and fourteen years old. I used to make quite a killing there. Sometimes I got three or four in a day to teach to dance.

And I remember there was a hymn that we used to sing at church which always, to this day, always reminds me of making valentines in front of the great big fireplace in our sitting room. It was a four-foot fireplace. My father loved that fireplace, and it kept going all the winter long. We had a board over a couple of stools which we'd make into our work table and we were making valentines, one afternoon, and for some reason or other, I don't know why, Mother was singing, "Jesus calls us, o'er the tumult" and my Auntie Blanche (Mrs. Herbert Smith) used to be up at Trinity Church. She was the dresser of the choir later on when I got to be in the choir. And dear Auntie Blanche had a voice like a steam calliope and used to sing, "Jesus calls us, o'er the tumult" so that you could hear it next door. We loved her but it was always a cause of great merriment in church when Auntie Blanche sang that. So I can remember sitting there, making valentines and singing like Auntie Blanche.

And we were talking about sounds and noises. Lying in bed on the south side of the house over the back door, I could hear Father when he went out to milk the cows. He had to go down the hall to the barn across the street, and the clanging of the milk pails as Father walked out with the empty milk pails is a sound that you always know, and Father whistling "the robin" or any birds because he used to whistle them all. I do it now. I do it at story programs. I do the chickadee. A chickadee will follow me all the way across the field from my house to the feeding station over in the woods if I call to him, and when I get over there, if there aren't any birds there, I can whistle them. But I got it all from Pa.

Just like everybody in the twenties, we grew asparagus. Concord was one of the biggest asparagus-growing towns and there were lots and lots of fields. Pa had, just on our little farm which was less than a hundred acres when I was a child, five different asparagus beds. You know you don't dig them up and replant them. They last for years and years, but when they begin to wear out and get old, you always have a new field coming on, because it takes three years to start cutting asparagus after you've planted it. We had asparagus and strawberries. We grew peas, raspberries, red currants and small crops of beans and carrots and beets.

Pa's love was apple orchards. When he first came as a bachelor in about 1906 ... sometime around there ... Anne and I have a fight about what year it was ... he planted what were then very unusual trees to have here. He planted Baldwins and Cortlands. Nobody had heard of Cortlands. And MacIntosh of course, which people did know. But he had Golden Delicious, which was an unusual thing. We had a couple of banana-apple trees too. And he had Red Delicious and Golden Delicious. And each orchard was known by its different name. The southeast orchard had all Baldwins in it, and the south orchard had the Golden Delicious, and the house orchard, which was behind the house, had the Cortlands and the MacIntosh and the northeast orchard had more Baldwins in it; that was a later orchard that he planted later on, further away from the house.

But I can remember stuff like foxes barking early in the morning when we had chickens in their summer range. They'd be all around the house, fenced off through the orchard behind the house. Foxes would jump the fence and go off with a chicken every once in a while, and we'd all be on the alert. It was a terrific thing. Sometimes they'd get so bold, they'd sit right in front of the house and bark, wait for you to open a window, and shoot them out the window. Pa got one right out the window of his bedroom one morning. I hated it when he shot them, but it also made me feel kind of shivery when I'd hear them calling out in the woods.