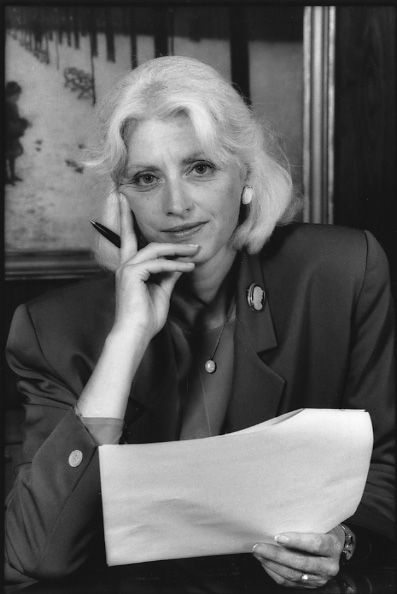

Marian Stanley

Polaroid Corporation, Vice President of Emerging Markets

140 Monument Street

Age 53

Interviewed May 16, 1996

Concord Oral History Program

Renee Garrelick, Interviewer.

Science and Technology Segment

Marian Stanley has worked at Polaroid Corporation for thirty years and is currently one of two women officers of the company. She describes the distinctiveness of the corporate culture that Edwin Land influenced.

Marian Stanley has worked at Polaroid Corporation for thirty years and is currently one of two women officers of the company. She describes the distinctiveness of the corporate culture that Edwin Land influenced.

When I first joined Polaroid in 1967, it was very much still a start-up company. When it was originally incorporated in 1937, it was formed by Dr. Edwin Land, the founder of Polaroid, around his invention of polarized lenses. Those lenses were anti-glare devices which he had hoped would be put into automobile windshields to prevent accidents. Dr. Land was hoping that these polarized lenses would be put into car headlights and car windshields as a safety measure. Automobile companies at that time were not interested in the idea. He was very disappointed but moved on to other inventions.

He was on vacation with his family in New Mexico, while still having this very small polarizing business he was struggling to get off the ground, and he took a photograph in New Mexico and his daughter who was 7 or 8, innocently asked "Why can't I see the picture right away?" Being the type of person he was, a very creative person, he wondered himself why she couldn't see the picture right away. He immediately started to think about how one could see the picture right away. He came back to Cambridge and shifted his sights from polarizing lenses to instant photography. He introduced the first instant camera in 1947 to a really astonished public.

In 1967, the company had had a tremendous growth period. It was a very hot stock, but also it had an incredible reputation as a very unique environment. The unique environment was very much a product of Dr. Land and the type of person he was and the type of people that he attracted. When I joined, I was a young teacher teaching in a small Catholic grammar school and I was halfway through my master's. I was teaching every subject to a group of 7th graders. There were 50 in the classroom at the time. I enjoyed it very much but for a young girl of 23, it was not an active social life with the children, the nuns and me. So I was eager to work with other adults who were not in a habit, although they were all lovely, lovely women. I happened to see an ad in the paper for a customer service representative, and I applied. It was not something that I thought about in terms of evaluating the company or the culture. I wanted a job where I could use some of my skills, but I honestly didn't think I would be working there very long. In those days, women who took jobs after college usually didn't think they would be working anywhere very long and I was really quite typical. So it was only an accident of fate that I stumbled upon this really intriguing company.

I was hired as a letter writer. In those days a letter writer responded to customers' complaints with these voluminous letters about how they could improve their photographs. We sat in small offices and spoke into dictaphones. I was surrounded by other women letter writers who were all the wives of men at the Harvard Business School, Law School or Medical School, also thinking that they would only be in these jobs for a few years then they would be replaced by another young woman who's husband was in some professional school. As fate would have it, my husband to be, and I married him when I joined Polaroid, was also in graduate school, so I was one of the many women who was there.

As I learned more about the company, I discovered over the next few months what an extraordinary place this company was and that it had a very special environment. Dr. Land had surrounded himself with extraordinary people. They were people who were not always credentialed people, but who were always extraordinary. He believed in the mixture of science and art so that many of the people that surrounded him in the labs were not necessarily scientifically trained. Many of the people that made the fundamental inventions for Polaroid photography were not scientifically trained. He had women running his labs which was quite extraordinary at the time. My first supervisor there, who was a tremendous influence on me, was a woman who had graduated some years ago from Smith. This had a tremendous impact on me as it was very unusual for the time.

His corporate philosophy was that the company existed for two reasons. One, to create useful and exciting products, and secondly, to bring the best out in people and give them useful, exciting work. This was called the dual aim or the two aims of the company. The first aim was exciting enough, but the second aim was very, very unusual in those times. We were constantly experimenting with different ways for people to contribute to the company, and it was important to create exciting jobs but to also create exciting products. As a result he was able to do both.

For example, the man that invented color instant photography, since the first instant cameras were black and white, was a man called Howard Rogers. Howard Rogers was an automobile mechanic that Dr. Land thought was particularly skilled. He gave Howard a lab and money and told him to go away and develop color photography. Dr. Rogers went away. (Later, he was an honorary doctor because he'd never even finished college.) He came back some years later with not much heard from in-between time, and said I think I've done it. And he had done it. Similarly the people that worked in the laboratories were not credentialed. The lab techs -- I ran a film program seven or eight years ago and the best scientists, if you consider empirical scientists, were his old lab techs who came to him out of the Navy or other such places and never had college educations. When I worked on the film program with them, it was so interesting. A couple still had tattoos up and down their arms. They understood the chemistry after working with him and so they understood empirically how the chemistry would react. It is really quite amazing. He believed that every person had enormous potential. Because he treated everyone that way, people responded.

He also worked constantly and in order to work with and for Dr. Land, you had to be completely devoted to him. He would call people many, many times, and there were many nights when they never went home. There were cots in the labs. There were many vacations never taken with families. He demanded and people were just dying to give him complete allegiance and complete control of their time. He was a very charismatic individual and enormously bright. The only other person with more patents to his name is Thomas Edison. The thing about him was not only his tremendous interest in science but his interest in all things; his ability to appreciate art and music. The way he expressed himself was really unique. I have a book of his essays in which he describes science and reading about the science, it is really quite beautiful. The writing is beautiful and his references are artistic references. He surrounded himself with a lot of beauty and a lot of color. He believed that each of our annual meetings was a marvelous adventure with lots of colors and showmanship.

He took care of his people in a very old-fashioned, paternalistic way but in a very nice way. I remember when I worked in customer service that we had a customer reception area where we were rotated when we were not writing letters. We had an old fellow called Dr. Jerry West, who apparently had worked in the lab previously and was always somewhat eccentric, but had clearly gone around the bend by the time I joined. He usually arrived at the customer service center on his bicycle looking as if he needed both a bath and a change of clothes. He would always be looking for more film or some such thing. We were just instructed to take care of Jerry West, so we like everyone else in the company took care of Jerry West by giving him film or cameras. We would talk to him for a very long time. When you worked in Polaroid it just wasn't considered odd. As I look back now I can't think of very many companies that would have absorbed some of the kinds of eccentrics that Dr. Land did.

The product at the time was getting more and more sophisticated. The first films were very beautiful but tended to fade. We moved from black and white to color. The cameras became more and more sophisticated. The cameras then began to be used for scientific and industrial applications. Actually right now our business is one-third industrial-medical-scientific, one-third business and only one-third consumer. That really started in those years. Our films began to be used for microscope photography, for ultrasound tests and a variety of other applications. As a result, our work in customer service became really quite complicated because you could have someone taking a birthday picture on the end of the telephone or you could have a scientist. I found that very exciting. We were given a list of people to call with questions so that we could always be able to respond to a customer, if not immediately but to get the answer. We were very well connected with all the scientists and the technical centers, which is really interesting for us.

Probably one of my most interesting experiences was when I was assigned to answer Dr. Land's letters, and that was customers who had written directly to Dr. Land. I would write letters for his signature which was very exciting for a young woman. As time went on, it was obvious to me, because my father had run a factory, that although the letter writing may have been a very charming way to respond to customers, it wasn't what customers were interested in when they got in touch with us. It seemed that they were interested in fairly crisp instructions and another pack of film. As I saw it the work designed to do that was really quite different from having cubby holes of offices with people writing very long letters. We established a crisper way to get back to customers, mostly by telephone but sometimes by postcards and just a pack of film.

As time went on, I was promoted within that small department to head of letter writers, etc. During this time, of course as a young person, I never really thought I would be at Polaroid for very long and then I began to take through the next 15 years what was quite a series of leaves of absence -- first to go back to school and finish my master's, and then I had four children and for each child I took a leave. It was really unusual for companies at that time to allow people to take these kinds of leaves. So Polaroid was really tremendously socially innovative. The first time I took leave I went back to school, but then I needed to pick up money because we were both in graduate school, so I would drop in and do some additional work. Then when my husband finished his doctorate, it seemed it would be a great time to drive across the country and I got another leave. All these things really very, very unusual. In addition, it was a time of tremendous change in the country. That was reflected at Polaroid as well.

During this time we had civil rights riots. Our little building was on Windsor Street in Cambridge near the housing project in Cambridge. We were escorted to the bus by policemen and we were threatened a number of times. It was a very strange environment. The building in back of us was the Margaret Fuller Settlement House which at one time was taken over by the Black Panthers. It was a bit of an unreal situation. In addition we had the Vietnam War going on. I felt quite strongly about it, and my first supervisor who I said was from Smith -- Dr. Land had quite a few women from Smith throughout the company -- was very upset because the students had very aggressively interrupted Hubert Humphrie during his speech. I said "Well, really important events are happening and you can't proceed as normal just to be polite." Well, for this woman that was quite an unique thought. That began a series of very interesting conversations. During one of the marches against the Vietnam War I asked to take the day off to march, and she was distressed but let me do that. I said I would work on Saturday. I came in on Saturday and there was Lois who stayed with me the entire day working silently. As time went on, her perspective on politics changed quite a bit.

In addition we had a tremendous situation in South Africa. At that time we had a distributor in South Africa called Paul Hirschon. Apparently he was selling our film to the government for identification cards to identify people from townships traveling to other townships essentially to curtail their activities. So that our film was being used really to curtail the civil rights of people in a country very far from home. Two of our black employees protested that by picketing in front of our headquarters. Polaroid was stunned, number one. I would say we were quite an insular company. We were very U.S. if not to say very Cambridge, and Cambridge behind MIT based so that this was an stunning experience for us. By some act of fate I was asked to respond to customer letters on South Africa because they started coming in. That was a powerful experience for me. We eventually ended up, I believe to our credit during those troubling months when we were actually trying to figure out what was happening and how we could be associated with such a thing, by withdrawing from South Africa. We have only just entered South Africa again last year. I just returned to South Africa this month as vice president of the company.

So it was a time of great growth in this company with tremendously interesting products, where you had the equivalent of a dark room and a small pod of chemicals with positive and negative, and you were completing all the steps in a dark room, in a color processing dark room, in 60 seconds. It is really an extraordinary invention. So you have this invention that the world just loved, you had this charismatic, extraordinary man who had created this culture that I don't think there was an equivalent in any companies that we knew of in the U.S. -- much in terms of groundbreaking approaches -- and thirdly, you had this dynamic experience of the ‘60s. So it was a very heady time for all of us.

As we moved on to the ‘70s, the products became more and more sophisticated and the marketing became more and more sophisticated. Previously it just sort of happened. We had sophisticated marketing campaigns such as a famous series of ads with James Garner and Mariette Hartley which for some reason were enormously satisfying to people and became kind of our trademark of advertisements. When we were at trade shows, we were always the hit of the trade shows, great showmanship. It was a high flying time. People stayed in very expensive hotels it seemed to me at the time. The money really flowed freely in the corporation.

When I first came to Polaroid in the late ‘60s the corporation was probably at about several hundred million dollars and we're at $2.4 billion this year. The number of staff at that time was probably in the single digit thousands, maybe under 5000, and we reached a peak about five or six years ago at 12-15,000 if you include international.

Even for that size of corporation in the early days it was extraordinary for people to feel that way about Dr. Land. If you didn't work for him directly, you felt it. Obviously, as the company grew and the people worked out in the factory which swells your population, people still felt intensely connected, but I think it was the Cambridge base which really had the deepest connection.

As we moved into the ‘70s, I started to have children so I took of course more leaves of absence. During that time again it was really quite unusual to have meaningful part time work in a major corporation. Polaroid being the company it was also allowed for unorthodox pockets of managerial styles. So what I did was essentially shop for managers who were a little unorthodox, and I got great part time work for all those years. During that time, Polaroid became much more professional in its marketing and the sales of its products. It went through some wonderful inventions. It built factories with incredible speed and was obviously a company with tremendous skill and tremendous cash reserves. We had a lot of connections with the universities in the area particularly MIT, and to a much lesser extent Harvard, though Dr. Land had gone to Harvard for two years. He graduated without a degree and only years later was given an honorary degree.

Polaroid started to level off in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, the result of a lessening of the product cycle. There were fewer more significant products coming out. They tended to be variations on the same products. At that time, Dr. Land also had invested heart and soul  very heavily in an instant movie system. He was absolutely right and terribly visionary in thinking about that, but he really hadn't taken into account the movie systems that were being created in terms of video photography, so that his instant movie system, which was really a marvelous system, had no sound and required a large player and other equipment and the customers were unwilling to invest in, at least to invest in a significant enough way to justify the investment.

very heavily in an instant movie system. He was absolutely right and terribly visionary in thinking about that, but he really hadn't taken into account the movie systems that were being created in terms of video photography, so that his instant movie system, which was really a marvelous system, had no sound and required a large player and other equipment and the customers were unwilling to invest in, at least to invest in a significant enough way to justify the investment.

At that time I was named Services Manager for this product to deal with all the customers that had had difficulty and eventually we phased the product out which was very painful and was a very big write-off. At that time Dr. Land was so crushed that he left the company in 1982, and I would say the character of the company essentially changed. If I had to think about a critical juncture that was really it. Number one the leader left and number two he had made a very bad call, so he was human. The whole thing was quite a stunning experience for the population at the time.

I personally only met Dr. Land two or three times though I wrote his letters and interacted on all these things. I was really operating always on stories. I guess in many companies with charismatic people that there are so many stories, and there were so many Dr. Land stories.

When Dr. Land left we had people that were trained as engineers within the company essentially took over the leadership position. The first person was Bill McCune who took over for Dr. Land. Bill McCune was a marvelously energetic, talented guy that had worked with Dr. Land for a long time. During the time of Bill McCune's tenure, once again I think probably one of the more extraordinary efforts was the building of the New Bedford plant which Mac Booth did. That plant went up in record time and was done so that we could stop depending on Kodak negatives. There were a lot of extraordinary engineering developments at that time, cameras that were really quite exciting for consumers. Again iterations of the basic invention of instant photography but iterations that customers found very compelling.

At the time that we were using Kodak negatives, and this is not my highest skill in reaching back to technology, essentially our product was a sandwich of a positive and a negative with a pod of chemicals between it that broke open as you pulled it out of the camera. That negative was purchased from Kodak. They were vendors to us. We felt very uncomfortable having this volume of film dependent upon a supplier that was not always sympathetic to our need for a reasonable cost of materials and was not always sympathetic to our needs for certain kinds of supplies, so the decision was made to build our own negative plant. This was a very difficult effort for us. It was a very complex factory. That plant went up in record time and it is still one of our most productive plants. At the time it was considered revolutionary and quite an amazing achievement. As I said, I did have a responsibility for a major film program perhaps six or seven years ago so I spent quite a bit of time down there, many nights down there. It is essentially one large machine coating negative that the entire factory is built around. It happens largely in darkness. When you see the machine first start up, you see the chemicals coming through and you often see these rainbow sheets of chemicals that are really quite beautiful. It is a very beautiful sight, highly automated and highly computerized.

I would say most of our achievements during this time were largely not basic science not fundamental science, but still largely exceptional, technical achievements. Within the marketplace, our marketing was probably at its highest level of achievement in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. The company really moved from that type of high profile marketing, high profile advertising to more muted kinds of advertising and more muted kinds of marketing. Only now is it once again approaching the similar approach to marketing and advertising that it had in the ‘60s.

As the company moved into the ‘80s, we encountered the problems that a lot of companies did in that we were struggling in some parts of our business. During that time we had a lot of different approaches and attempts to reinvigorate the product line. Some were successful and some were not. Probably the most significant events of the ‘80s in my mind had to do with our discovery of ourselves as an international company. This is when we started to move overseas with our product and discovered it was very successful there. We started to build plants overseas in the ‘70s and ‘80s. We built a plant in Enscede, Netherlands and in Ireland which we did not maintain for a variety of reasons. We later sold it actually to Digital. We built a plant in Vale of Leven, Scotland which is one of our major plants. We started to establish overseas subsidiaries in Japan, Germany, the UK and Korea. We have subsidiaries all over the world now, but this was really just the beginning I believe under the aegis of a fellow called Dr. Young who led the way for us in that regards.

Russia is a very exciting story. In the mid'80s we not only decided to concentrate on what we would call mature developing markets as we were establishing our business in all of these countries, but we elected to focus on some of the new emerging markets. We chose three -- Russia, China and India as markets that were problematic, but we felt were not enormous and had great potential at some point in time. I think this decision shows great foresight, and it reminded me of Polaroid in the early days, of something very, very big that really can't be explained because of course, when we went into these markets, people thought we were crazed to be in Russia in 1986, China in 1986, India in 1986. In India the film tariffs were 200%, in China it was 80% on cameras and 50% on film, very problematic leadership; in Russia we could barely find a place to open an office. The system was so inefficient and there were no customers. In Russia and China we had to have a joint venture. In Russia the Svetesor plant was a joint venture with the atomic energy commission., and in China it was with the Shanghai Motion Picture Limited company.

It was really Bill McCune through his technical contacts who had a vision of what Russia could be. As a result, we had a small team that worked on these three markets. Russia in 1986 actually gave us no profit or no sales to speak of. We started to see some sales in about 1993 of about $1.3 million, then currency convertibility hit, and we were probably the only company, because we had created a structure that was poised to take advantage of it, that lept last year to well over $200 million, and this year Russia will be our largest worldwide subsidiary. We celebrated five years of opening our new office in Russia last year with a celebration called Picture America and 25,000 Russians took part. It was an extraordinary experience. In China our business doubles every year. We did over $40 million last year and we'll do in the high $70 or $80 million this year. We have five offices including in the interior. We have a large factory in China that makes a million cameras and two million circuit boards. We have significant business in China.

In India we just got our 100% owned subsidiary which was an achievement. We had the film tariffs reduced from 200% to 21%. We put our own senior manager in there, and we have a factory there that manufacturers industrial hardware, and this year it will begin manufacturing our large volume consumer cameras. So the internationalization of Polaroid really happened I would say starting in the ‘80s. Today well over 50% of our volume comes from offshore. We also have factories in Mexico.

Each of these international markets are somewhat different. I would say Russia is the exception. Russia is largely a consumer market. There are no mini-labs in Russia so when people started taking all those rubles out from under their mattresses which we're convinced they were in little jars in every kitchen, they went out in groups and usually it would be an apartment building that would buy a Polaroid camera and then share it. Each family would buy a pack of film for special events. There were no real mini-labs that could process their pictures efficiently for them so instant pictures were absolutely the ticket. The extraordinary thing is that we have really only concentrated on St. Petersburg and Moscow. We haven't gone outside those two cities, and we have not gone into our industrial occupations at all, so that the potential in Russia is really staggering to us.

In most emerging and developing markets, our biggest business is in passport identification and government programs like drivers licenses and things like that. We also have what I consider is the beginning of consumer photography in street photography which is a very big market outside this country, and that is in markets where people cannot afford a camera but can afford a picture. So there are small entrepreneurs at temples, festivals that take pictures of a family for a fee. Every time a street photographer takes a picture like that, of course, he is doing a product demonstration for you, so that as time goes on and the economy improves, people can understand instant photography, they are familiar with it, and you've got your market development done. Street photographers often times form unions and organizations. I have a very large picture over my fireplace painted by the head of the Indonesian street photography union. They are very competent people who know how to take instant pictures very, very well and sometimes they are quite artistic, and so the pictures are quite nice.

During this time Polaroid also decided to concentrate on other developing markets and so we've entered markets like Vietnam, Indonesia, Peru. All of these markets are generating quite a significant amount of business for us, and they really changed our lives a great deal so that Polaroid has come a long way in terms of how it views itself in the world. It views itself now not so much as a Cambridge company but as a world company. It's employees are not only U.S. citizens but from all over the world. The officers of the company are very different now.

When I first came to Polaroid the officers of the company were all white males who had been technically trained often at the same institution and they tended to live in the same towns. They were all wonderful men and amazingly expansive in their understanding of people as time went on and the world changed in their willingness and desire to give people of a different gender or a different race an opportunity. It was still very much a company of white males of goodwill. Today if you look around the officer ranks of the company, you will find two senior women, one of whom is me, the head of all of manufacturing is headed by a woman and that was always the most plum job in the company that makes it extraordinary for it to go to a woman within the company, the head of one of our business research units was born in Egypt, the head of our research and development group comes from Bombay, we have two black vice presidents and the head of Asia Pacific is black. So this is really quite an exceptional transition for the company that I think Dr. Land would have approved of. Our vision as a company is significantly more expansive than it was when I first joined. The product has changed significantly now into many more electronic imaging products. There are many ways to take a picture other than photography. We are into non-silver material. Photographic material is customarily made with silver and that is the basis of photography ever since photography was invented, but with new technologies, electronic technologies, you can have a non-silver material with a thermal material or ink jet material that makes a very beautiful image so that we are now selling those, and we have designed a really very fine medical system, a non-silver medical system.

The dry or non-silver process is interesting because ordinarily it is very difficult to get as beautiful a grain in an image in photography. It's very difficult to get that any other way than photography, however for medical imaging, a product that is dry is obviously much more useful for the hospital, and a product without all those chemicals to wash down the drain obviously is much more healthful for the environment. We see our future in products like this in contributing to both the cost needs of the hospital in not having to have big dark rooms but also to the environmental restrictions that all of us are placing on ourselves now.

We produce scanners now. We produce electronic digital cameras. We sell entire systems with databases and software linkages. We have a very big electronic imaging group with a very large software contingent. We're opening our first software development center outside Delhi, India in a development park so we are as much connected now with computer companies as we were in the early years with camera companies.

With consumer products you tend to get obsolescence. For our industrial products, you'll often find camera backs that are refreshed, repaired, etc. but they've been around a very long time. Consumer products tend to need refreshing after three or four years. You need to continue coming out with new lines in order to keep the franchise refreshed, and it has to be something that appears significant to the customer and different. That's a tremendous burden for consumer products companies but as they say, it really comes with the territory. For professionals and industrial users I would say it is not quite the same. They are really interested in functionality. As far as functionality is concerned, if you look at some of the old cameras made, they are very fine, beautiful cameras, Leica lenses, and the old black and white films took very beautiful grain, fine toned, nice soft contrast, very nice products, so for consumer franchise, you do have to refresh but for some of the other customers, functionality is more important.

I think the company is at a very important juncture. One of the other important elements of this has been the capacity for dramatic change that this company has had. When I was given an opportunity six or seven years ago to be on the Board of Directors, I was on that board by virtue of Mac Booth who followed Bill McCune as president, because Mac had agreed to have an employee or actual worker sit on the Board of Directors, which again was unusual. He really led tremendous change for the better in terms of worker participation in the company, as well as the beginning of medical imaging products and some other big technical changes that took a great deal of courage. I can remember from the board seat seeing much as I do now that the vision of the company is at another stage of enormous change, technical change. We get closer and closer to more of a computer software kind of environment as we become far more international and our locus or our center of interest is no longer Cambridge, Massachusetts; it's in other world capitals. We now have a young CEO, Gary DiCamillo, who has succeeded Mac from outside the company with a business marketing background, tremendous energy, so I see another chapter with great change and I'm very, very hopeful about where we'll go next. Our new CEO came to us from Black & Decker. His family came from Niagara Falls, New York and they own a bakery there. It's highly successful and besides that makes a wonderful biscotti that's sold through Bloomingdales. He went to RPI, another engineer, but then he went to Harvard Business School and has really come up through marketing careers at Proctor & Gamble and Black & Decker. He maintains a tremendous energy, but I would say an old-fashioned view of what a good company, not exactly a bakery, but a good work ethic and a sense of the population as a community, which is very good.