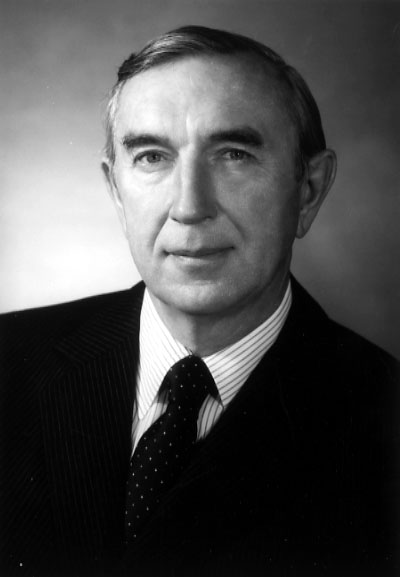

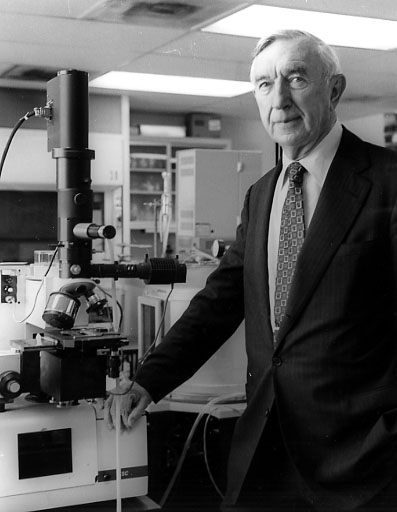

John Magee

Chairman of the Board, Arthur D. Little, Inc.

Acorn Park, Cambridge, Mass.

Age 69

Interviewed September 26, 1996

Concord Oral History Program

Renee Garrelick, Interviewer.

Science & Technology Segment

At the occasion of Arthur D. Little's centennial, you delivered an interesting speech before the American Newcomen Society in which you described the origins of the company and how Dr. Arthur Dehon Little sought to bridge the gap between scientific theory and findings emerging from academic research and business purposes with the intent of benefiting both industry and society. In 1921 Dr. Little dramatically illustrated the capability of the company to solve impossible problems by creating a silk purse from a sow's ear; as you explained, 100 pounds of sow's ears were needed to make two silk purses, one of which is displayed at the Smithsonian Institute, the other is at Acorn Park. Your own career with Arthur D. Little has spanned over 45 years. How did you happen to come to work for a company that has been known as the problem-solvers?

At the occasion of Arthur D. Little's centennial, you delivered an interesting speech before the American Newcomen Society in which you described the origins of the company and how Dr. Arthur Dehon Little sought to bridge the gap between scientific theory and findings emerging from academic research and business purposes with the intent of benefiting both industry and society. In 1921 Dr. Little dramatically illustrated the capability of the company to solve impossible problems by creating a silk purse from a sow's ear; as you explained, 100 pounds of sow's ears were needed to make two silk purses, one of which is displayed at the Smithsonian Institute, the other is at Acorn Park. Your own career with Arthur D. Little has spanned over 45 years. How did you happen to come to work for a company that has been known as the problem-solvers?

It was in 1949 and I was working for the Johns Manville Company in their building parts plant in Manville, New Jersey. I was a financial analyst studying operating problems in the plant. I received a call one day from a person I'd never known and never met before, a man named Harry Wissman, who worked at a company in Cambridge that I had only very occasionally heard about called Arthur D. Little. Harry wanted to talk to me about a new activity that the company was embarking on and explore the possibility that I might come to work as a junior staff member for this activity that he was going to lead. It was called operations research, which is based on the principle of using scientific research methods and quantitative methods to explore operating problems. It developed in the military services during World War II, and Arthur D. Little was undertaking to translate that area of work or thinking into business and industrial practice.

I had studied mathematics and economics in college. I had completed an MBA at Harvard and had done some graduate work in mathematics at Columbia. I really didn't want to go into engineering or science and was looking for some opportunity to explore and use mathematical methods and quantitative methods in business. At the time it seemed that perhaps the only real opportunity was in the actuarial field, but I had explored that and wasn't too interested. So I had gone to work at Johns Manville, and when this call came out of the blue, it sounded very much what I had been looking for over many years. I was delighted to have the chance to interview Arthur D. Little. The area was very experimental, very uncertain, but they made it particularly attractive by offering me a $1,000 increase in my pay which was $3,500 a year at the time. That was enough to overcome any concerns I had about the risk. I finally joined the company in January 1950.

Dr. Little founded the company in 1886. Actually his doctorate was an honorary doctorate. My recollection is that he never quite finished his bachelor's degree at MIT. He had to leave because of financial concerns. He worked in industries around the area -- the paper making industry in particular, and was interested that so much industry was based on skills that were in the head and hands of people, but were not communicable. They really weren't explicitly understood. He had the insight that the principles of science, which were then largely defined in the academic world, could be brought to bear to understand industrial processes in effect to build technology, so that you could better control processes, make better products and by understanding processes, improve their efficiency and quality. He founded a little laboratory in downtown Boston to pursue this dream. Most of the work at the beginning was materials testing because among other things, in order to control the process, you had to know what the inputs were. This was a place to start.

From that beginning he began to spread out and do some consulting assignments. For example, he consulted with a fledgling manufacturing company called General Motors on the establishment of their first research laboratory. He focused primarily on physical processes, not entirely but primarily, and probably in particular on chemistry-based processes. He became particularly interested, for example, in the use of petroleum as a base for a chemical industry, which up until World War I had been based on coal. He built the first pilot plant to refine petroleum and break it down, and it was the beginning of the American petrochemical industry. As the company grew and struggled through the ‘20s and ‘30s, it still primarily focused on solving product and process development problems for its clients. As the ‘30s passed, many companies whose product base was technology, the chemical industry for example, began to be concerned not only about developing products but also developing markets and understanding competitive advantage in markets. Dr. Little's firm began to help clients understand their market and business position based on the technology that they had and he had helped them develop.

At about the same time, in the late ‘30s, the investment community began to get particularly interested in technology-based companies as investment vehicles. But they didn't understand really what this technology was all about, so they turned to Littles for help in analyzing the investment potential in particularly the chemical industry. That was the beginning of another thread of work at the company, studying the economic potential of technology.

Still another development was the work in the late ‘30s for Puerto Rico called Operation Bootstrap. This was designed to help Puerto Rico develop a strategy for economic growth and expansion, again based on the technical advantages and economic advantages that Puerto Rico could prepare. So Littles became the architect for Operation Bootstrap. In that way the company grew from its focus on product and process development in the physical sciences into areas of business and economic and investment concerns. Then after World War II when the company was able to refocus on its primarily industrial client base, the so called management or consulting thread really began to flourish based again on studying the markets and strategic issues growing out of new technology and helping various parts of the world develop their economies based on economic advantage and exploitation of technology, and of course through the development of the operations research end of it, which is where I came in. The company really focused on those two main areas of work, management services and technical and process product development through the ‘50s and ‘60s.

Late in the ‘60s we began to see emerge a whole new stream of issues. We began to realize that we were living in a closed system. There wasn't an unlimited supply of fresh air or fresh water, and there were third party effects arising from industrial activity and urban growth and various forces, so the company was drawn into work helping clients understand the third party effects and how to manage and control them. One of our first assignments was for a large chemical company where the Board of Directors was shaken to discover that the company had been inadvertently responsible for a major disaster because of a chemical spill into a nearby river. The board asked Arthur D. Little to help them develop a strategy and an audit process within the company to make sure that these accidents didn't arise and to minimize the chances of them.

At the same time the federal government was beginning to take a hand on environmental issues. The Environmental Protection Agency was established, and we undertook work for that agency to help it understand what was technically feasible in the various industries where they had a concern -- chemical, paper, steel, automotive, whatever. Out of that work has grown the third major thrust of the company which is the work in environmental safety.

Through all this period yet another force had been at work. The economies of the world has been growing together because of advances in technology, communication and transportation, and also because of economic and political forces. Littles has expanded globally in parallel with that. The company started as a little laboratory in downtown Boston and gradually expanded to work throughout the United States and North America, and particularly after World War II in the ‘60s and ‘70s, into Europe, Asia and Latin America. It is now truly worldwide in its activities with a substantial share of its staff in offices as far away as Bombay, Moscow and Hong Kong. There are 52 offices in 30 countries with a global staff of about 3000, of which about 1300 are here in Cambridge and the balance are in various offices around the world. Cambridge is our primary laboratory base although we have another expansion base in Cambridge, England. People in Cambridge, England love to refer to their location as Cambridge One.

I don't know if Arthur D. Little is the first consulting firm in the country. I don't know that that is a relevant question. I'd like to think that we're the best. I'd like to think that we have the best balance in terms of focus on the actual development of technology, and the use and management of technology for our clients. Certainly we are among the oldest. The field of consulting has its roots in banking, accounting, law and all these roots go back certainly into the 19th century, so I couldn't really quite say that we are the oldest, but we like to think we're the best.

When Arthur D. Little began to construct his site on Memorial Drive in Cambridge it was called sarcastically "the research palace" because at the time it seemed like an incredibly big establishment for doing industrial research -- a building that nobody would ever be able to fill. That was about in the third decade of the company. Around the time the company was established the Director of the U.S. Patent Office had offered to resign on the grounds that everything worth patenting had already been done. So there really wasn't at that time of the turn of the century an understanding of the potential in technology. At the time of the turn of the century technology thinking would be based primarily on physical science. Today I think we can think of the term much more broadly in terms of technology based on not only physical science but human understanding and social concepts.

Arthur D. Little had lost a partner, Roger Griffin, who was killed by burns caused by a laboratory explosion. Dr. Little also had a nephew, Royal Little. Royal Little was a remarkable person. He and his mother lived in the West, and his mother sent Roy back to live in Boston with his uncle to be educated. So Roy grew up in Arthur Little's household in Brookline. He did not want to join Dr. Little's firm. He wanted to be a businessman and entrepreneur and established himself in the textile industry, then took over a small company called Textron. He used Textron as the base to acquire the American Woolen Company which was just about to be liquidated and then Textron grew into a major multi-industry company. Many people used to refer to it as the first conglomerate, but Royal Little hated the term because to him Textron was not just a collection of disparate companies. It was a system that took advantage of cash flow from various parts of the company to reinforce the growth of other parts. So it was a very well managed enterprise. Roy was a very close advisor to his uncle even though he never joined the firm. He was on the Board of Directors, and Roy was the one who in 1954 engineered the establishment of the Memorial Drive Trust, which was the vehicle by which the ownership interests in the company, the majority ownership interests, were transferred from a trust for the benefit of MIT to this new trust for the benefit of the staff. It became a retirement plan, and the Trust is still the majority owner of the company.

The Memorial Drive Trust was really the first employee stock ownership plan, but it has gone far beyond that. The Trust bought the interest in the trust that Dr. Little has set up at his death. It went on to buy in the balance of the shares of the company so that the Trust owned 100% of the company by 1960. The Trust was funded by contributions the company made from its earnings for the benefit of employees. Then it began to invest in other activities and it has always been one of the important venture capital investors in the Boston area. Today it still holds the majority interest in the company as well as a diversified portfolio of other companies.

The company in 1969 was owned 100% by the Memorial Drive Trust. There were some very interesting technical issues related to that 100% ownership. At that time there was an enormous difference between the capital gains rate on income and our highest income rate. I think the numbers were something like 20% on capital gains and perhaps between 70-90% on ordinary income. If a person took their accumulated interest in the Memorial Drive Trust in a single payment, that was subject to capital gains. If they took it in more than one payment, it was subject to ordinary income. That was one part of the story. The company being 100% owned by the Trust had no established public market value so the question of what the company stock was worth and just what does employees' interest in the Trust mean, because the company was a major part of the Trust investment, was a subject for analytical determination. The Trust tried to value the company stock reasonably conservatively, but the Trustees recognized that they were potentially subject to challenge by the IRS. The IRS might assert and establish that the company shares were worth a lot more than the MDT said they were. The point of all this is that if the IRS ever accomplished that, then that would mean that the people who had withdrawn their shares from the Trust for retirement in the preceding years would have been underpaid, and they would get another payment. That would mean that they were getting more than one payment and they would be subject to ordinary income tax, and the IRS would be a great winner but the employees would be big losers. In order to establish a public market or establish an objective value for the stock, the Trust decided to sell shares to the public market and have it a publicly traded stock and then they would have a measure they could point to. That was an important reason for the Trust selling part of its interest. They always intended to maintain a majority ownership. They also felt that possibly if the company had a publicly traded stock that the company might use that stock for acquisitions or other stock.

Now as time went on, first of all, the tax laws changed really eliminating capital gains treatment for withdrawals. The company demonstrated that it could finance its growth with some acquisitions out of its own earnings, and we never did use our public stock as a vehicle for making acquisitions, except for one or two small cases. But still having a public stock sort of exposed us. It exposed our finances, our financial records and our balance sheet to outside eyes. In 1987 for example, we were approached by a small publishing company in New York who wanted to buy the company. They wanted to buy it from the Memorial Drive Trust. It would have been a totally inappropriate step. We were able to convince our Board of Trustees and our outside shareholders that we should stay in the Trust. But we decided that really there were no net benefits to the company and we could much more effectively move into the future as a partially held company held for the benefits of the employees. Today the company is very much substantially employee owned. There are some interests in the company still held through the Memorial Drive Trust by retired employees. But our goal is to have ownership of the company held by active employees either through the Trust or through an ESOP or through other arrangement which employees, particularly non-U.S. employees, can build their equity interest in the company.

One of our presidents was Jim Gavin. He was a remarkable person who grew up an orphan in Pennsylvania and was adopted. He went into the Army as an enlisted man. He was admitted to West Point, became a young officer. He always had a streak of innovation in his makeup. He became very interested for example in airborne operations. He was one of the early paratroopers. He had a remarkable record in World War II. He was made a general officer and a division commander at a very young age, came through the war, was injured, a real hero.

In the late ‘50s the military strategy of the United States seemed to be based primarily on the use of the atomic bomb and big bombings. Jim, who was at the time chief of research and development for the Army, felt that that strategy was flawed, and that the country needed a highly trained technically supported mobile Army force to deal with the kind of threats that the country might face. I think it has been demonstrated since that he was right. He was asked in 1958 to go before Congress to testify in support of the proposed military budget at the time, and he refused to do that. He could not in good conscience support the budget, and he said so in public and resigned. About that time the company Board of Directors were reviewing the future management -- people like Earl Stevenson and Ray Stevens were approaching retirement, and Royal Little in particular was concerned about the future leadership. He happened to see some newspaper stories about Jim Gavin and became interested in him. Here was a man who was a leader, who was innovative, was not afraid to speak his mind, who had a strong interest in technology, so he invited Jim to investigate the possibility of coming to Arthur D. Little. That's how he came here.

In the late ‘50s the military strategy of the United States seemed to be based primarily on the use of the atomic bomb and big bombings. Jim, who was at the time chief of research and development for the Army, felt that that strategy was flawed, and that the country needed a highly trained technically supported mobile Army force to deal with the kind of threats that the country might face. I think it has been demonstrated since that he was right. He was asked in 1958 to go before Congress to testify in support of the proposed military budget at the time, and he refused to do that. He could not in good conscience support the budget, and he said so in public and resigned. About that time the company Board of Directors were reviewing the future management -- people like Earl Stevenson and Ray Stevens were approaching retirement, and Royal Little in particular was concerned about the future leadership. He happened to see some newspaper stories about Jim Gavin and became interested in him. Here was a man who was a leader, who was innovative, was not afraid to speak his mind, who had a strong interest in technology, so he invited Jim to investigate the possibility of coming to Arthur D. Little. That's how he came here.

He came first as head of what was then called the management services division. It managed all the management consulting activities and I was a member of that activity. I got to know him then and traveled with him and developed a great respect for him. He then succeeded to the role of President and then Chairman and Chief Executive of the company, and I worked directly for him for many years. I came to have enormous regard for him. He was always a person with great moral courage. He had gone to Paris as Ambassador to France for about two years at the beginning of the Kennedy administration. But then he came back in about 1962 and from then until the early ‘70s he was Chairman and Chief Executive.

I became President in 1972 and stayed in that role for a few years and then I succeeded him as Chief Executive and then was made President and Chief Executive until 1986. At that time I took on the role of Chairman and Chief Executive. Charlie LaMantia, who had worked in the company as a head of our chemical engineering activity for some years in the ‘70s and had left for a few years, came back as President and then in 1988 I turned the role of Chief Executive over to him.

The food and flavor technology area, the laboratory, has been an important area of the company's work for a long time. It probably began to develop in the middle of the 1920s and grew during the ‘30s and was part of the company's focus on building a base and technology to help countries to improve their products and processes, and in this case substantially in the food industry. It flourished because of a number of factors. One the techniques for growing food, processing it, preserving it, preparing it had changed enormously, and by being able to treat issues of flavor and odor in a systematic way, the company has been able to help its clients adapt these processing and preparing technologies and still maintain the quality of the product or improve the product. At the same time it has been an important resource to help us work with clients on problems of environmental control. It's not an issue of making a good odor better, but one of dealing with the elimination of environmental issues arising from gases, etc.

The lead pencil project has always been one that engaged my interest just because it illustrates how technology can be brought to bear to improve even as old and as simple a product as the ordinary lead pencil. We were approached by the Empire Pencil Company, a major manufacturer of lead pencils, some years ago. They were having problems in getting adequate supplies of the clear wood that is needed to make pencils by commercial fashion and they were having problems with cost and quality, breakage in leads and so forth. It's a rather complex, labor intensive process to produce pencils. They asked us to help. The ultimate consequence of this project was the development of a technique to extrude lead pencils using powdered wood and powdered graphite in a plastic binder so the pencil is basically extruded into a single pass like a long piece of spaghetti and then chopped up. The pencil feels like a conventional pencil and writes like a conventional pencil but is much more uniform in make up and quality. It's been a tremendous success, and it has always intrigued me because when people ask if we work on high technology projects, I bring this example up and say making a lead pencil better is a high technology project. It's really very sophisticated technology on an old fashioned product. The pencil we saw is about 30 feet. It was just a joke. As a gag, the people in the laboratory produced this long pencil.

Arthur D. Little has been active in work in space for a long time, really since the beginning of the American interest in space. Out of that interest arose the work or the special capability we had developed in thermodynamics. One of the characteristics of space is that, depending on if you are facing the sun or not, you are either very hot or very cold and managing that difference through good thermodynamic engineering is a capability that we happily were able to bring to bear for the space agency. Therefore, for example, in the Apollo program, the exploration of the moon, we developed or we actually built several of the major experimental devices. One of them is still operating, a laser reflector that is used to determine very precisely the positional relationship between the moon and earth. We've done a lot of other things in relation to space projects. For example, we've been working on the development of devices for space stations for the future. One of the interesting projects we worked on is the understanding of what happened to the famous Apollo 13 explosion which was the subject of a movie. There was an explosion aboard the flight and the crew had to bring the crippled Apollo spaceship back and land. We were part of the investigation to determine what really happened. In fact, Jim Fletcher the commander of that flight, wrote a book about his experiences which was the basis for the movie. He gave me an autographed copy of the book which I passed on to the then chairman who was the leader of our project, and at the same time I passed on to Jim Fletcher a copy of the ADL report that described what happened.

I think we're the only corporation that has as part of its activities an accredited degree granting graduate school. This year it has about 65 students from all parts of the world in its graduate Master's degree program. In addition, the school manages short programs for individual clients or on specific management projects. The program began in the early 1960s when we had a large economic development project supported by the Agency of International Development to help Nigeria plan and execute a major economic project. As part of that project, we had an obligation to train our counterpart Nigerians to carry on the work. We found it very difficult to keep the counterparts in place working with us in Nigeria because they had so many other things to do. We were frustrated, the agency sponsors were frustrated and the Nigerian government was frustrated, so it was determined that the only way to train these people for the future was to bring them outside Nigeria, bring them to the United States in a special training program where they would get an intensive education in business practices, in economics, in the relationship between government policy and develop a relationship between government and corporate settings. We undertook to identify various universities who might put this program on without too much success. We had one or two experiments with universities in the northeast that didn't work out too well. Finally we established a joint program with Tufts at the Fletcher School, but a number of our staff taught at the program drawing on their own consulting experience and their own work in economic development. It had very much of a sense of reality to it. The cases that were studied were based on circumstances that the Nigerians could also use on domestic U.S. business issues. Out of that, the program became full time here at Arthur D. Little. Then the Ghanaian mission heard about it and asked if they could send one or two students, and then the AID mission in Tanzania heard about it and pretty soon we had a multinational program. Then we began to attract people from Latin America and the Middle East, and eventually we discovered that we truly had a business education program. Sometime later we felt and the students felt that they were working at least as hard professionally as their counterparts in universities who were getting degrees, so we decided to apply for degree granting authority. It was really a first. Despite some reservations in the academic community, we were given the authority to have an accredited Master's program. To me it has been a successful, satisfying program.