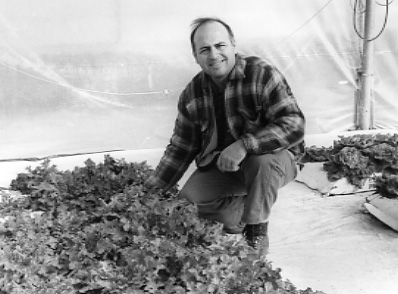

Nat Arena

Arena Farms

167 Fairhaven Road

Age 50

Interviewed January 13, 2003

Concord Oral History Program

Renee Garrelick, Interviewer.

Nat is the third generation of Arenas to farm in Concord.

--Third generation Concord farmer. The Arena Family-Grandfather Natale

immigrating from Italy settled on Old Bedford Rd. Worked for Wilfred Wheeler on

Sudbury Rd. Purchase of land Sudbury Road farmland. During winter worked in

Maynard mills. Dominance of asparagus crop, problem with asparagus rust. Middlesex

County as the number one agricultural county in the U.S. in the early 1900s.

--Third generation Concord farmer. The Arena Family-Grandfather Natale

immigrating from Italy settled on Old Bedford Rd. Worked for Wilfred Wheeler on

Sudbury Rd. Purchase of land Sudbury Road farmland. During winter worked in

Maynard mills. Dominance of asparagus crop, problem with asparagus rust. Middlesex

County as the number one agricultural county in the U.S. in the early 1900s.

--War production board and farming during World War II. Father John Arena farming during the 1950s, need for diversification. Risk and hurricane destruction. Dependency on leasing land, different soil variety. Agricultural Preservation Restriction and deeding of agricultural land in perpetuity.

--Organic farming and the consumer. Supermarkets and local growers. Bag culture and protection against root disease. Commercial professional association of growers:Boston Market Gardeners Association, New England Vegetable Growers, New England Vegetable and Berry Growers Association. The last Concord grower? Reduction in number of growers, fewer young people able to go into farming and purchase land.

--Shared technology and marketing with A. Arena Farms, premier lettuce operation in the state-run by Uncle Angelo and Cousin Nat- fatal 1989 explosion. Current expansion of Arena Farm, retail outreach. Local New England farming of smaller fields spread out in area but with strong population customer base.

My grandfather, Natale Arena, came to this country in the early 1920s. He arrived in the North End as there were some friends and relatives there. It is my understanding he was told there was work out on the farms in Concord. He came to Concord in the ‘20s and starting working for Mr. Wilfrid Wheeler, who owned a lot of land around town. Over the years my grandfather was able to settle the whole family out here on Old Bedford Road. That's kind of how he got his start. In the ‘40s he was able to purchase this land that our current farm stand is on now. He moved the whole family to the house they built which is the house that is still right here.

Back when my grandfather purchased the land in the ‘40s, our land went along Sudbury Road near what is now Crosby's Market. At that time it was the old coal tipple for the trains coming into Concord. It extended all the way up into what is now Arena Terrace across Route 2. Route 2 was built in the ‘30s and it ruined the farming out here. It was brought around the edge of town through some of this land out here thinking that this was not a desirable location now that the highway was coming through here. That probably, if anything, lowered the value of the land in this area. I believe it was almost 100 acres at the time my grandfather bought this land. Part of the reason that we are still here as we go into the 21st century is back in the ‘50s when most other farms in Concord sold out completely, my grandfather was able to develop part of the non-farmable land across Route 2 that is now Arena Terrace. He sold house lots, and I believe at the time it was $1,500 per house lot up there. That was able to subsidize the operation of the farm through the ‘50s. Selling bad asset kept the good farmland in production into the ‘60s. It was divided in the late ‘50s into two parcels. One my Uncle Angelo operated and one my father John operated.

My grandfather had four sons. The oldest was Natale and then Pat, Angelo, and John. He also had two daughters, Josephine and Mary. The eldest son went off to World War II and sent letters back to Mr. Wheeler at the time talking about the agriculture in Italy that he was seeing and ideas he would be bringing back with him, but unfortunately he didn't come back. So of the other three brothers, Pat left the farm and went to work in a foundry type situation, and Angelo and John ended up splitting the parcel that was left and each got approximately half.

I understand that through the ‘30s my grandfather worked off season on helping to build Route 2 and he would hold other jobs in the winter. I recall my father saying that my grandfather used to walk from Concord to Maynard to the mill to work in the winter and walk every day to Maynard and back. I believe there was a trolley for a dime but it wasn't worth it to him to spend a dime for the trolley.

My grandmother was Santa. She actually came over from Italy because my father's mother passed away I believe in the early ‘30s. Now here was a widower with four sons and a daughter sitting in a house in Concord. The Italian community was relatively established at that time and you know people talk to people, and one of the neighboring families up the street, the Alesis?? said well, we've got someone who would probably come over and marry you and that's what happened. Santa Arena came over from Italy and really didn't speak much English. Even as a child growing up, I remember most of the time, it was Italian that she spoke. She could understand some English but she came over and took over the family and had a daughter, Mary. It was a step-family type situation but she stepped into what must have been a tough situation with four sons and a daughter already here.

In the off season most of the farmers worked on whatever was going on in the area. If there was factory work available, they would do that. I can remember my father even in the off season through the ‘60s into the ‘70s would drive a school bus for the town of Concord. Of course, growing up in town he knew every street so he was the spare driver. Anybody who didn't show up for their assigned time, he could go out on any of the 20, 30, or 40 routes that were established and he knew all the routes, so he could substitute for anyone. That would be first thing in the morning and then he would come back for his greenhouse work to do. Then he'd have to head back into the school bus for the afternoon.

What was grown in this area in the early part of the century was asparagus. This was the asparagus basket of the world. Middlesex County, in fact, was the number one agricultural county in the United States back in the early 1900s. This was before there was really Florida agriculture and way before California agriculture, so this county has a major historical part in agriculture in the United States. A lot of the technology that helped farming around the country and around the world was developed in this area. Even the Waltham butternut squash that revolutionized squash production in the ‘50s was developed here at the Waltham Field Station. A lot of the carrots from the late ‘40s and early ‘50s were developed here. Waltham broccoli was also developed here and that kind of revolutionized broccoli production. So it was kind of the mecca for agriculture up until probably the late ‘30s — early ‘40s when it started to shift away.

During the ‘40s, at the time of World War II, farmers were assigned specific crops to grow. That's my understanding and it's been told to me that root crops like carrots and radishes were really asked for by the War Department. There were lots of greenhouses in the Lexington area. There could have been 100 acres of greenhouses. Today I don't think there's three acres of greenhouses. There were many, many greenhouses and their crops were traditionally winter lettuce because if you wanted lettuce in the ‘20s and ‘30s you didn't get it shipped in, you had it grown locally. That was the only way to get it. But as the war production board decided what was important that these root crops would be grown on the east coast and brought into Boston, and then they could be shipped right across to Europe and they would survive. They would be able to hold for a few weeks and still be a good product. I know our family was asked to grow a lot of carrots and I believe they also grew a lot of radishes and parsnips. In fact we still have the old diesel tractor that was like a War Department diesel tractor that the family got in 1944 to work the fields. I believe it was the first diesel tractor in Concord. I can remember probably up until 1970 or so that the tractor was actively working. At the time a diesel tractor could use the number 2 fuel oil or diesel fuel which was less of a priority for the war effort than the high octane gasoline which the airplanes needed. It was a way to shift from gasoline tractors to diesel tractors.

The asparagus rust problem really started taking hold in the ‘30s, and the crop was virtually gone by the late ‘30s. This was a problem of a soil borne disease getting established that the varieties of asparagus that were being grown were all very similar so it was something that once it got established, it really caused a big problem. A lot of people don't realize that asparagus is a perennial crop. You seed it and it takes five to seven years to pick the first spear of asparagus, so it's something that you've got this big upfront investment. Now you do pick it for 20 years once it's established, but if it runs into a problem, it takes five to seven years to get back into it.

Following World War II in 1946, my grandfather built the farmhouse here. He was able to purchase this land all around here and with the three boys and the two girls, I guess it was pretty crowded in the small house on Bedford Street and so he built a nice new house out here on the edge of town on Fairhaven Road. That's the house that is here today.

The progression was the house was built in 1946 and then I believe the greenhouse was built soon after that, 1948 and 1949, and the first small little farm stand went up in 1949. With the turn off of Route 2, you could put three or four cars in there at any given time but that was all you needed. There was not a lot of traffic on Route 2 at that time that's for sure.

Where Nashawtuc Country Club is now there used to be an Andy Boy farm. That is a company that is still in existence today out in California and Florida, and one of their first operations was out here in Concord with all those nice fields. The problem was it was in the flood plain of the Concord River. In 1954 and then in 1956 we had multiple hurricanes in a given year and the flooding was extreme. I've seen photographs of them out in a canoe picking broccoli. Again broccoli is a long season crop, but at that time of the year there really wasn't such a thing as a spring broccoli crop. You would grow the plants all summer long and start harvesting probably in late August and harvest in September, October and even into November. So when a hurricane hits in early September, it hits while you have all the expense of your crop in the ground and you haven't brought anything in yet.

My father was also greatly affected by the hurricanes in the ‘50s. He was basically a carrot grower at that time and had purchased all the line equipment to have an 8 or 10 man crew pack carrots. He had the digger machine that would go out in the field and be able to dig the carrot quickly, and the carrot washing system where you could dump the carrots in. It would go through this washing machine and on to a conveyor belt where it could be packed into one pound bags and shipped out. He was probably growing at that time 60 acres of carrots, which is a lot of carrots. To grow a real good carrot generally you need a soil that's got some clay in it. The fields in Sudbury where he was growing this had some clay in it, and if you get 20 inches of rain, you can't even walk on that field for, as it turned out, weeks. What happens is the carrot soil is water logged so long that the carrots rot. It was just like submerging them totally in water. So for two out of three years there he basically didn't pick a crop. That lesson was the lesson to diversify. Never should one crop be the crop that is produced. My ideal would be that no one crop is more than 10% of what we do. That's what we've worked toward here for the past 30 years is that there is no one thing that we do that if something happens to that crop that is financially devastating, no matter what season, there is always some crop that is going to grow really good and some crop that is not going to grow really good. So you just have to have a wide spread of things you're growing that you can't get hurt by a very wet year or a very dry year.

We don't just farm land in Concord. We lease property all over the place. We actually have about 26 acres of land in Sudbury that we were able to purchase in the late ‘70s. It was one of the first APR parcels that became available. APR is Agricultural Preservation Restriction which means that this land is perpetually deeded as agricultural land, that the state and the town got together and contributed money to the landowner to take the development rights off the property. So if you've got land that is worth $10,000 an acre as building land and worth $1,000 an acre as farming land, the difference is $9,000 an acre, which gets paid to the landowner. He signs off the deed on the building rights, and the land is now agricultural land and can be sold as agricultural and is taxed at agricultural land at much lower value which theoretically farmers can afford down the road. I think it was 1978 when this very first parcel was available in that program.

At the time we went to the Concord Coop Bank to take out a loan. I remember having to convince the bank people that this was an okay thing that if we weren't able to pay off the loan that other farmers would want it and that it wasn't useless land. To their credit they stood behind us, and we did pay it all off and it's now ours. I believe the total amount we financed was only about $16,000 in the late ‘70s and I think we did it for a 15-year loan. It wasn't a long-term loan. But that particular parcel that we purchased has all different kinds of soil types on it. There's everything from very sandy soil to very clay soil there and with our kind of operation that grows all kinds of different things it was an asset. Most other farms would want all similar soil types. If they're growing pretty much one or two different things, you would want basically uniform soil, but for us growing hundreds of different things, this was perfect for us. We're still there today and it's still very productive. In fact the giant pumpkins that we've grown the past few years have come off that property. It's about 26 acres and there's about 20 acres of usable farm land. There are still old stone walls and ponds and it's just a very picturesque New England little valley out there. But we've had to lease land from the town of Wayland where we've had that land for many years. We still lease a few parcels from the town of Lincoln. We have land in Concord that is National Park land that we lease from the Park Service. We're pretty much still dependent on this leased land in the area to keep our agricultural production enough to supply what we're looking for.

Leasing land can be very unpredictable. It's better now than it was 20 years ago. Then you would go to lease land and it was always just for one year, so every year you would have to reup the lease. If you limed a field and lime is a long-term land modification that you wouldn't be able to get use of that lime for a year or two, and you might lose that parcel next year. So at my urging and with help from the State Department of Agriculture a uniform lease procurement policy was established with towns, and now the standard lease is five years. I would still like to see more of a long-term lease arrangement worked out with farmers. I would love to see 10 or 20 year leases on these properties or at least that you get to reissue the five-year lease unless the farmer has really done something wrong. But again this is becoming a political issue in some towns, and leases are given to non-profit organizations and to politically active organizations to do who knows what with. It's kind of my opinion that farmland that is designated as farmland should be available first to active farmers in the area. And if there is no farmer looking for land then it can revert to some other use. Farmers are going to be the best stewards of the land. Farmers were environmentalists 100 years ago. All these fields that have been designated in the town of Wayland, where did they go when they needed a new well, they went to where the farm was and promptly restricted the use of the farm land around the well. Well, for the 40 years the land was used they tested the well, and it was fine. But now that they're pumping water from there, you can't farm it. That's what kept the land in good shape to begin with. So there are some crazy things that go on out there. It's like a "catch 22".

Organic farming started taking off about 20 years ago. Crops grown organically were perceived as being something that was healthier and better for you and free of pesticides and that people kind of started looking for this product. I remember at the time all the supermarkets all of sudden set up organic sections, and most of those failed. Within a couple of years, they weren't there any more. That would have been in the early ‘80s. That is something that we as growers kind of keep an eye on but we realize that the food product that hits the shelves in the United States is by far the best and cleanest. A good clean source of food is what's contributing to the rise in the standard of living and the rise in the longevity of people. Most people when interviewed would say that they would buy organic and they will check off the proper politically correct boxes. But when given a choice at a supermarket of buying green beans that might be a little bent, have a little spot or two on them, or other green beans that are virtually perfect, and the spotted ones are $1.99 a pound and the perfect looking ones are $.99, a lot of that organic checkoff goes out the window as they pick up the $.99 beans. Supermarkets know that people shop with their eyes. Supermarkets take big advantage of that. A lot of the growers around the country who are the big wholesale producers know that, and they will produce varieties that look really, really good.

What we can do as local growers because we don't have to ship things five to seven days, we can produce a crop that not only looks very good but it tastes good too. When we're ordering seed from seed catalogs there are thousands of varieties of all kinds of vegetables and small fruits, and one of our things to consider is what is this going to eat like. Ultimately, people are going to eat this product and being a direct farmer to consumer person, the people who buy it from us if it tastes good they're going to come back and buy it again whereas a supermarket situation, the grower selling to the supermarket knows that the buyer is just interested in how good does it look and how good is it going to look seven days from now. That‘s the only thing driving their variety selection is the fact that this strawberry is rock hard and will ship across the country. What really gets me is the vine-ripened tomatoes that are picked dead green and they go into a box that says vine-ripened. Then on the way north their boxcar is filled up with ethylene gas which is a natural ripening agent and all those green tomatoes turn red in about 3 days. So what you're getting on the shelf is a very firm, which people love, bright red, which people love, green tomato. That's why it doesn't have any taste. So what we as local growers are able to do is to grow tomatoes that really taste good. That is the one crop that people have not lost their taste buds about. Most people will know a good tomato when they taste it and that's what gets them back here. That's why we grow those greenhouse tomatoes in the spring, and spend all that time and energy and effort. I haven't been able to verify it but we may be the only place in the state that has grown greenhouse tomatoes from the late ‘40s to 2003 virtually every single year. I think the only year we missed was the year of the fire in 1995, and it just took us one year to get our tomato crop established and another new greenhouse was put up.

Back in the old days we used to steam sterilize the soil. I would get home from school and it was my job to go in there and dig a ditch in the greenhouse, two 35' ditches, 2 1/2-3 feet deep, lay a metal perforated steam pipe in there, hook it up to an old fire hose and we'd run the steam boiling and literally cook the ground to 180 degrees, put a plastic tarp over it and run a four or five pound steam crusher so the tarp would puff up, and then it would have to cool for a day. You would go in the day, kind of clean your shoes off so you wouldn't contaminate the steamed soil, and then you have to dig the pipe back out of the hot soil, which would still be hot. Then redig a new trench in the cold soil immediately next to it and move the whole system one greenhouse section. Steaming the soil sterilized it because with greenhouse tomatoes, if you had a disease going in the greenhouse, it would quickly spread from plant to plant.

We were probably one of the first farms to use the new bag culture back in the early ‘80s. What we would do with the bags is we started out with bags of potting soil and we would grow two or three plants in a bag, so if you had a disease get started with a plant, it would only go as far as the back, so you would only lose two or three plants. You wouldn't within a short time lose between 20 and 30 tomato plants to a root disease that would get going. I can remember at the time I went down to the dump and picked up old electric valves off of old washing machines and that's how I hooked up the watering system because each bag needed a little tiny hose going into it because you couldn't hand water. Automatically three or four times a day these electric valves would kick on and that's how I watered those first crops of tomatoes. Now, of course, there's really equipment you can buy that will do the job, but back then you had to improvise.

We've managed to extend the growing season longer and longer. That's one of things that some of the state universities have really helped with. When I was up at UNH, a lot of the research was being done with plastic row covers and plastic mulches on the ground, so this is something that's been what we've done from the long term, and just year after year looking at ways to get a little earlier jump on the season, and possibly with frost protection in the fall extend the season another week or two. That's important in New England. Our growing season is limited.

In New England we're fortunate to have a very good association of growers. It's started out as the Boston Market Gardeners Association and then evolved into the New England Vegetable Growers, and it's now called the New England Vegetable and Berry Growers Association. This is the oldest growers association in the United States. I believe it got started in the 1890s or late 1880s. What we do is we have four winter meetings a year and we'll bring in people from around the country who are experts in their particular field of whatever we want some information on, be it new varieties of sweet corn or new weed control methods for pumpkins and squash. There is a lot of research work done at various universities around the country, and we'll get that person here with his report that probably isn't even published yet to talk to our growers. So this gets the information directly to the people who can use it, and it's been a very good thing for agriculture in New England. It's still trying to be duplicated other places around the country. There are other associations out there now based on what was established here in New England and Middlesex County back in the late 1800s. And it's a good active organization. We have about 400 active members right now and again primarily you have to be a commercial vegetable grower and earn your living doing that. New members apply to the organization, and if they are an unknown entity, someone in the area will go out and see what kind of operation we're talking about. If it's somebody growing a little backyard garden, that doesn't get you into the group. You have to be someone who is attempting to make a living growing fruits and vegetables. That gets you into our organization and gets you all the benefits and the camaraderie and information. Growers will always help each other. There are some growers who are not members in the Concord area even, but Concord over the years has been a real location of some of the top people in the organization. I was fortunate about 10 or 15 years ago to be elected president of the association and served my two years, and I'm still active on a couple of committees. I've been kind of busy here the past few years trying to rebuild after the fire we had but it's something that I really realize the benefit of this organization.

For years we had the original small farm stand which was maybe 15 by 20 feet. and that was added to out the back, added to on the left side, added to on the right side, and lean-to upon lean-to for a number of years. Back in 1975 we did a major reconstruction where we kind of consolidated the footprint of all these various lean-tos under one massive roof and we were able to do that over the course of a summer, building it ourselves without closing. I still don't know how exactly we did it but we did. We put this whole new building up and simply built over the top of everything that was there, and then pulled everything down on the side, and we were open every single day and not closed for one.

This new building is a little bigger and more ambitious than that. It is in a completely new location that up until the time we were going to put the building there was basically open field. But our intention is when we do move into it this summer that we will only be closed for a day or two as we move operations from our current buildings into the new setup and be open for business on a given Monday and closed probably on Tuesday and Wednesday, and open in the new place on Thursday. Of course, everybody will work like crazy for two days to accomplish that but that's what we want to try to do when it's time to move in. Initially in the new setup, what we want to do is exactly what we've been doing but just be able to do it better. It's very difficult to sell produce out of a greenhouse like we've been forced to do for seven years. No matter when the sun comes through the roof, it heats up in there, and to be in a building with a real roof, that's going to be a thrill again. It's going to be so much easier to be in a building that is organized so that each department has its own area that they can preassemble things and get things ready to go out to sell is going to be very good. In the produce area you can get produce from the field, bring it in the back door, wash it, get it ready to go out, bring it out front to sell it, and it doesn't interfere with the cut flower department or the plant department or the various pottery and other plant gifts that we put out there. Each department has its own specific area that it can operate in and all departments can run at the same time, which is going to be very good. As we get ourselves reestablished with everything that we've done in the past, then we're looking at what other new things we should be doing. We want to get our salad bar back in operation because we did have that in the old setup and we know how to do salad bars. But we've also realized that today people want prepared foods. So you can come in and you can get a little container of something that you just take home and heat and eat it up. There's all that preparing that you would have to spend time doing, but we can do it more efficiently and use top quality product to do it. I think that's going to be the difference over what you would get at another prepared place. That carrot we're using was growing that morning and you're eating it that night. There's not too many places that can claim that.

Even though I'm going to have my 50th birthday later this year, I'm still considered a young farmer in comparison to other current Concord farmers. Thirty years ago when I was first on the board of the New England Vegetable Growers Association I remember going to one of the first meetings of the board of directors, and the next oldest member was more than twice my age. There are some young growers coming along but not too many in this area it seems. It's something that unless you're born into it, you're not going to be able to afford to go buy land and establish a farm. The Agricultural Preservation Program is trying to help that out so that growers don't have to pay $200,000 an acre to go buy land. There should be some of this restricted land around that you can pay substantially less for, probably less than 10% of that, and potentially keep farming and be able to grow crops and sell crops and earn a living. I don't see any vast influx of young people into agriculture at this time. It's still something that's difficult, especially the vegetable end of the business. The greenhouse end of the business is something a little different, and I think there are a lot of younger people in that. It doesn't quite cost as much to get going, the return is better. We see us as being a farm that does everything that we very rarely get a complaint about someone buying a geranium for $3.00 or $4.00 but buying a tomato at $3.00 or $4.00 a pound, that gets some comment.

I think growing with other farmers is something that is really going to happen a lot more in the future as there really are not that many farmers left around here. We're going to make more of an effort of what we have historically done some of which is try to talk to a local grower, see what they are growing, and find out if what they're growing anyway will be something that we then don't have to produce ourselves, and we can then buy their crop. We had done this in the early ‘80s with Mr. Breen on the other side of Concord. He was a great grower of strawberries and we would just over there and purchase all his strawberries from him. In fact we would send our crew over to pick them for the most part, and that worked out great for him. He had a ready market for all the strawberries he could grow. It worked out good for us as that is a very specific crop and we didn't have to try to produce a strawberry crop and we could focus more attention on our other produce crops. Mr. Breen lived in what is now the Thoreau homestead on Virginia Road. That's another nice little parcel of land out there that if a commercial farmer got ahold of it, could probably do a very nice job with it long term. But over the past 10 or 15 years there have been various groups in there trying to do what they can to do other than growing crops for commercial purposes. It's something that I think is not really the best use of the property.

I've never thought about the fact that I may be the last grower in Concord. I would expect that as the next 10 years evolved. There would be someone else stepping into some farm around here that will be younger or just able to get on top of the situation going on at that particular farm. We don't know what's even going to happen with our particular farm in the next generation. The oldest of the next generation is still only 10 years old, so no determination has been there, that's for sure. It's something that traditionally you had to grow up on a farm to be able to operate a farm. Experience is worth more than any schooling you can get. I went to school, I studied plant science, I did everything that college could teach you and it did teach me a lot, but the experience of being in that particular field for 10 or 15 years and knowing what happens in that particular field, that's at least equal to whatever technical scientific things you can learn in college. Agriculture is a science and an art to do it the way we do it growing for retail and growing over 100 different things.

I have a younger brother and two sisters with kids and again it's available to any of them who express an interest in agriculture. It's available to them to come up and take advantage and test it out. There are many other easier ways to earn a living. To me it's satisfying. I really never had any doubts growing up that this was what I wanted to do. It's always a challenge. It's always something different. Every season is different and every year is different. It's almost like a baseball team or whatever, all the pieces could work for one year and then the next year, one little thing is different and that throws everything off and you have to change things. We could have the best plan in the book April 1. Everything is all planned out for the whole year. April 10 something happens that's not on the plan and that plan is gone for the season and now you're trying to stick to the plan but realizing that you have to improvise. Whatever the elements give you you have to try to take advantage of and just work with what you've got for that season. You can't just say we're going to grow 40 acres of corn come hell or high water because you will get both of those over the years.

Our new operation will allow us to have more outreach directly to the customer. I think again that's what people like about coming to a local farm. They're talking to the people who are growing the product. If they've got a question or comment about a particular item or if we're trying a new variety of something, we can talk to customers and say, "How do you like this new green pepper or is there something about it we didn't consider in the way you prepare it or cook it?"

I can remember when super sweet corn came on the market a few years ago, there was a new technology. This was back when I was president of New England Vegetable Growers, and I remember saying at the time it's going to change the way we sell corn. You don't need to get the pot boiling any more, run and get the corn, and throw it in the pot. These new varieties don't have the enzyme that converts sugar to starch so you pick the corn and the sugar that is in the corn stays in the corn, it never gets converted, it just stays there. You can pick that ear of corn and put it on your counter for three days, then peel it and throw it in a pot of water, and it is still 95% as sweet as the day you picked it. You couldn't do that with regular corn. In a matter of hours, that corn would have respirated. The corn is still living and it using up its sugar to continue to try to grow. So within hours all the sugar sweetness in the corn is converted to starch and it just becomes very bland. So now when we grow our sweet corn and pick it, we'll pick a truck load of corn and it might be that that corn lasts two days. We don't have to go out every single day and pick. Most of the time, we do, but if we know it's going to be a very rainy day the next day, or a very hot day and the corn will overgrow, we will pick it when it's ripe and bring it in, and we don't even have to refrigerate, we just pour some water on it and keep it hydrated and that corn quality is excellent. That's new technology that really has changed the way people thing about sweet corn. We sell sweet corn in the stand now starting in March from Florida. Fifteen years ago we never sold sweet corn unless it was our own because it never tasted any good. Why sell something that didn't taste any good? But this corn that is the super sweet hybrids, the major difference is tenderness. There are some varieties that keep really, really well but they're very crispy, very hard even after you cook them. And there are others that grow a nice big ear and they're tender and those are the ones that we can try to grow.

I think what helped our end of the business, Arena Farms grow was the A. Arena Farms. These were two independent operations yet we shared technology, we shared equipment at times, why should we both have this certain kind of cultivator if they only needed to use it 5 days and we only needed to use it 5 days, we could share that piece of equipment. Again we helped each other out with marketing of wholesale product. We had big shippings to Stop & Shop and other supermarkets in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s and their operation was the premier lettuce growing operation in New England. A. Arena Farms was my Uncle Angelo and my cousin Nat. All the first sons are named after the grandfather. So our family has had three Nat Arenas, but the family rated them by date of birth as Nat I, Nat II, and Nat III. At Christmas you would look at Nat and then look at the Roman numeral after your name to know if that was your present or not. I was Nat I. The operation that Angelo and my cousin Nat had down the street was by far the premier lettuce operation in the state. They had the only hydrocooler operation in the state in which you could pick lettuce out of the field and put it through the machine and it would take all the heat out of it and then you could ship it to a supermarket and it would arrive with its temperature in the 30s. Again the supermarkets liked the fresh stuff but it had to be able to keep for a week. The only way to accomplish that was to take that field heat right out of it. That's what the people who wanted to buy the product needed so that's what we did. That's kind of been our mantra over the years is whatever customer we're talking to is what do you need. Then it's our job to provide that. I think that's just a good way to go about what we're doing.

In March 1989 in addition to farming my cousin Nat had various trucks and equipment. He had his own trailer truck for delivering his own product and the plow truck for the state and the sander trucker. He would do all his repairs himself, and he had a complete garage down there. He was very knowledgeable about anything mechanical. He had rebuilt a couple of vehicles, and framed up restorations of old vehicles. He was very knowledgeable about that. This particular week the truck was being used by Agway to store their frozen foods. This was the same truck for the WBZ farm stand that he would give it to them for a week so they could put their product in it for when they had to have their sale of product to benefit Children's Hospital. The truck had a flat tire and he took it back and was preparing to fix that tire, and basically it exploded before he even had a lot of air in it.

He knew the procedure for doing a split rim tire, had the chains on the ground and everything, it was just a fluke. Near as we can tell, the tire rotated on the rim, created rubber dust inside the tire, and when he slammed the tire on the ground, dust floated up, rubber dust is organic like grain dust. You've heard of grain silos exploding. He had a leak on the rim and he went to weld the rim up and that rubber dust inside probably ignited and blew up the tire. My uncle was in the building at the same time and he was severely injured, never really came back 100% and passed away about 7 or 8 years later, and my cousin Nat never knew what hit him. I believe at the time he was 32, a few years younger than me. Again we helped each other out and it was a great situation to basically have another farm right down the street. Between the two of us we were probably the largest agricultural operation in the state at the time. It's left to me and my brother John to carry on. We're doing what we can but we're definitely focusing on the retail and kind of carrying that forward with the new building to really allow us to properly display this bounty of product we've been able to produce over the years.

In New England the biggest crop is customers. If you look around there are lots of houses, lots of people. If you go to other parts of the country, the midwest even the California valley area there is not the huge population immediately adjacent to the fields. So they have to ship distance to get to their market. We're fortunate in New England that our market is all around us. We just have to work with much smaller fields much more spread out. We go as much as five miles away with our tractors to work fields. So that's the disadvantage. But again the advantage is that there are a million customers within 25 miles. So that's too bad of a tradeoff.