|

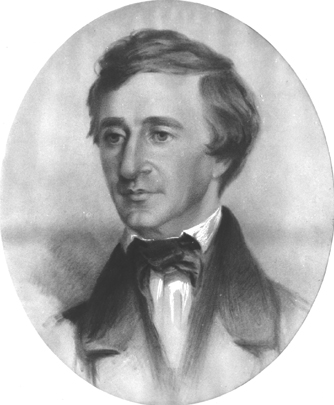

HENRY DAVID

THOREAU

31. Samuel Worcester Rowse. Henry David Thoreau,

1854. Crayon on paper. From the bequest of Sophia Thoreau,

1876/77.

By the late 1830s, Emerson had befriended Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862). Born in Concord, Thoreau was, over the course of his life, an author, lecturer, naturalist, student of Native American life and collector of Native artifacts, surveyor, pencil-maker, social critic and active opponent of slavery. He returned to Concord after graduating from Harvard in 1837. In 1841, he joined the Emerson household as a handyman and caretaker. He stayed with the Emersons from 1841 to 1843, and again in 1847 and 1848 (while Emerson made his second European trip). A close bond developed between the two men. Emerson—fourteen years older than Thoreau, much-demanded as a lecturer and well-known as a writer—filled the roles of teacher and patron as well as friend to Thoreau. As time passed, the master/pupil aspect of the relationship became less satisfactory and less appropriate. But in the early 1840s, it suited both of them. In the early days of their friendship, Emerson revealed in his journal obvious affection for and appreciation of Thoreau. On February 17, 1838, for instance, he recorded in his journal, “My good Henry Thoreau made this else solitary afternoon sunny with his simplicity & clear perception.” On September 1st of the same year, he referred to Thoreau in a letter to his aunt Mary Moody Emerson as “a brave fine youth.” Writing his brother William on June 1, 1841, he described Thoreau as “a scholar & a poet & as full of buds of promise as a young apple tree.” Later, he would write with regret of Thoreau’s failure to fulfill this promise. Whatever distance eventually grew between Emerson and Thoreau, Lidian and the Emerson children were always fond of Thoreau. In Emerson in Concord, his lengthy Social Circle biography of his father (published in 1888 in the Second Series of Memoirs of Members of the Social Circle in Concord; also published separately), Edward Waldo Emerson recalled Thoreau’s stable presence, his usefulness about the house and garden, and his particular rapport with children. Under Emerson’s influence, young Thoreau increasingly turned his thoughts to writing. While living in the Emerson house in the early 1840s, he enjoyed Emerson’s encouragement, support, and advice. He also benefited from access to Emerson’s library, which included works of Oriental literature of great interest to Thoreau, books not readily available elsewhere. And when members of the Transcendental Club came to visit, Thoreau was welcome among them. Thoreau contributed to The Dial during this period, and edited the April, 1843 issue for Emerson. His first book, A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, appeared in 1849, his Walden in 1854. Emerson and Thoreau shared the common bond of grief from January, 1842, when Thoreau’s brother John died of lockjaw and Emerson’s first child, Waldo, died of scarlet fever. By 1850, the friendship between the two was strained. Despite their respect for one another, Emerson’s early sense of Thoreau’s literary promise and Thoreau’s initial idealization of Emerson did not quite match the reality of how each conducted his life. Thoreau did not vigorously pursue the visible success as a writer of which Emerson thought him capable. Emerson increasingly became a man of the world and traveled in literary and social circles that Thoreau disdained. When Thoreau died of tuberculosis in 1862, Emerson delivered his eulogy at the First Parish. It was later expanded for publication in the August, 1862 issue of the Atlantic Monthly. The piece, titled “Thoreau,” clearly conveyed Emerson’s sense of disappointment in Thoreau. Emerson commented, for example, on Thoreau’s combativeness: “There was somewhat military in his nature not to be subdued; always manly and able, but rarely tender, as if he did not feel himself except in opposition … It cost him nothing to say No; indeed, he found it much easier than to say Yes. It seemed as if his first instinct on hearing a proposition was to controvert it, so impatient was he of the limitations of our daily thought. This habit, of course, is a little chilling to the social affections … ” Emerson’s final judgment on what Thoreau had achieved affected his friend’s reputation well into the 20th century: “Had his genius been only contemplative, he had been fitted to his life, but with his energy and practical ability he seemed born for great enterprise and for command; and I so much regret the loss of his rare powers of action, that I cannot help counting it a fault in him that he had no ambition. Wanting that, instead of engineering for all America, he was the captain of a huckleberry-party.”

No image in this online display may be reproduced in any form, including electronic, without permission from the Curator of Special Collections of the Concord Free Public Library.

Next Entry - Previous Entry - Back to Section IV Contents Listing - Back to Exhibition Introduction - Back to Exhibition Table of Contents |