VI. FRANK SANBORN

In July of 1853, Harvard student Franklin Benjamin Sanborn walked from Cambridge to Concord to meet Ralph Waldo Emerson, who talked to the young man in the study of his home on the Cambridge Turnpike—ten life-altering minutes that later resulted in Sanborn's permanent residence in Concord. In 1854, Frank Sanborn was invited to become master of a small private school here. His coeducational Concord School on Sudbury Road (the present 49 Sudbury)—opened in 1855. It offered a progressive curriculum, with frequent excursions, dances, amateur theatricals with the Alcott girls, and considerable personal freedom. Its faculty featured local talent—Henry David Thoreau, for example, who lectured and took the students for walks, and Elizabeth Ripley, who taught German. Sanborn's pupils included Edith, Ellen, and Edward Waldo Emerson, Julian Hawthorne, Sam Hoar (son of Ebenezer Rockwood Hoar), the Mann boys, and Wilkie and Bob James.

Sanborn found the town sympathetic to his already well-established abolitionism. Simultaneously with teaching the children of prominent local people, he pursued activities that eventually put him at odds with the law and in 1860 focused national publicity on the town. He served on committees for the colonization of Kansas and for the protection of settlers determined to keep it free. As secretary of the Massachusetts Free Soil Association, he traveled west in 1856 to report on the progress of Free Soil agitation. He met the radical John Brown in Boston the following winter, and became a zealous supporter of Brown's cause. He joined forces with Theodore Parker, Samuel Gridley Howe, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, George Luther Stearns, and Gerrit Smith, who with Sanborn comprised the Secret Six—members of the Massachusetts Kansas Committee who supported John Brown's goal of arming a slave uprising and who helped to plan and finance the unsuccessful raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia) on October 16, 1859.

His foreknowledge of and complicity in what was prosecuted as an act of treason prompted federal scrutiny of Sanborn after the failed attack. Following Brown's capture, Sanborn fled twice to Canada. The month after Brown's execution, he disregarded a summons to appear before the Senate committee investigating the conspiracy. Finally, on the night of April 3, 1860, federal marshals caught up with him.

Deputies showed up at his home with a warrant for Sanborn's arrest, and a vigorous and noisy struggle ensued. Sanborn was handcuffed and carried, resisting, toward a waiting carriage. His sister's screams alerted their Concord neighbors. William Whiting and his daughter Anna Maria (also known as Ann, Anne, and Annie) rushed to Sanborn's house, yelling all the way. The church bells were rung, and a crowd soon gathered. Aided by their townsmen, Sarah Sanborn, Colonel Whiting, and Miss Whiting did their best to rile the horse, or horses (some of the details of the episode vary among the multiple contemporary and retrospective accounts), and otherwise to prevent the deputies from getting Sanborn into the carriage. John Shepard Keyes—Sanborn's lawyer—showed up and, assessing the legality of the situation, asked Sanborn if he wished to petition for a writ of habeas corpus (by which a person in custody is brought before a court or a judge to determine the lawfulness of his arrest, and may thereby be released from detention). Sanborn answered in the affirmative, and Keyes rushed off to the Main Street home of Judge Ebenezer Rockwood Hoar, who prepared the writ, which was delivered to Middlesex County deputy sheriff and Lexington Road resident John Brooks Moore, who formally presented it to the deputies and demanded Sanborn's release. When they refused to surrender him, Moore on the spot appointed members of the crowd to serve as his posse comitatus, which overpowered the deputies and rescued Sanborn by force. The hounded deputies escaped from Concord in their carriage, followed for some distance by a group of hostile locals.

Sanborn was committed to the custody of Monument Street resident George Lincoln Prescott (son of Timothy Prescott, half-brother of Martha Lawrence Prescott Keyes, brother-in-law of John Shepard Keyes, and, later, a Concord Civil War hero and casualty). The next day John Moore took him to the courthouse in Boston, where a group of Concord and Boston abolitionists (Wendell Phillips included) showed up to demonstrate support. The Massachusetts Supreme Court, over which Chief Justice Lemuel Shaw presided, found that the warrant had been served illegally and ordered Sanborn's release from custody. When Sanborn stepped off the train at the Concord depot, he was met by a cheering crowd. A public protest meeting was held in Concord that night.

The story of Sanborn's attempted arrest and rescue was seized by the press. It was reported triumphantly in Garrison's antislavery paper The Liberator, and featured (with dramatic engravings) in such widely read periodicals as Harper's Weekly and Frank Leslie's. The incident placed Sanborn and Concord at center stage in the national drama leading up to civil war.

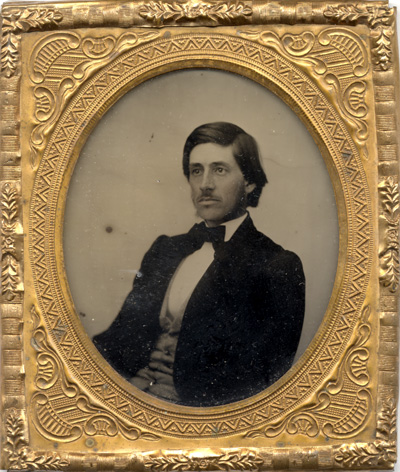

70. Ambrotype portrait of Franklin Benjamin Sanborn as a young man. CFPL Vault Collection.

|

|---|

|

|---|