ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATION, CENTENNIAL OF UNVEILING OF DANIEL CHESTER FRENCH’S SEATED EMERSON IN THE CONCORD FREE PUBLIC LIBRARY, CONCORD, MASSACHUSETTS

FRIDAY, MAY 16, 2014

REMARKS BY LESLIE PERRIN WILSON (CURATOR, WILLIAM MUNROE SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, CFPL)

Thank you all for turning out to celebrate the one hundredth birthday of Daniel Chester French’s statue of Emerson seated.

Thank you all for turning out to celebrate the one hundredth birthday of Daniel Chester French’s statue of Emerson seated.

This marble wonder was unveiled in the library on Saturday, May 23, 1914, on the eve of the First World War.

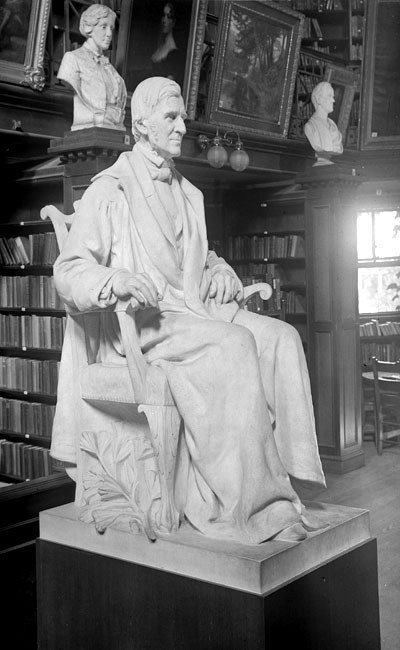

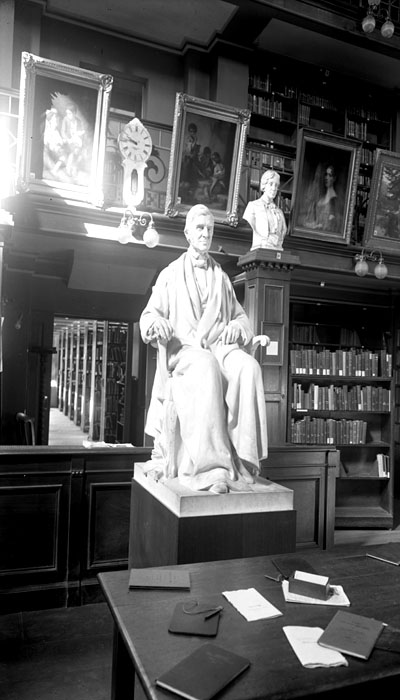

It may come as a surprise to some of you that the statue did not always sit on the spot it now occupies. It was originally placed so that Emerson faced visitors as they walked into the front door of the library, as shown in photographs taken by Herbert Wendell Gleason in 1920. The statue was moved to its present location when the library building was renovated and expanded in the 1960s.

This evening, before we enjoy cake and bubbly, I’d like to spend a little time placing the seated Emerson in context.

The crowd gathered here that day in 1914 was honoring a tradition established in 1873, when the Concord Free Public Library first opened its doors: the recognition of Ralph Waldo Emerson as the patron saint of this place. Long before 1873, Emerson was integrally associated with the culture and intellectual life of the town—through its Lyceum, its commemorative celebrations, its school committee, and the several libraries (private and public) that preceded the Concord Free Public Library. So it was no surprise that when this library opened, Emerson both delivered the keynote address at its dedication and served on its original Library Committee.

Emerson’s importance to the library was early acknowledged through the acquisition and public display of key pieces of Emerson portraiture.

In 1873, David Scott’s oil portrait of Emerson was purchased for the library by three Emerson associates: Judge Ebenezer Rockwood Hoar, Emerson’s friend and the first president of the Library Corporation (the private, non-profit entity responsible for the property, buildings, valuable holdings, and endowment of the library); Hoar’s sister Elizabeth, fiancée of Emerson’s brother Charles, who died prematurely in 1836; and Reuben Rice, like Emerson, an original member of the town’s Library Committee for the Concord Free Public Library.

The Scott portrait—which has been continuously on display in the library ever since—now hangs in the Reference Room. Painted in Edinburgh in 1848, during Emerson’s second trip to Europe, it reflects the fact that by the 1840s Emerson had a transatlantic as well as a national following.

Next to the Scott portrait in the Reference Room hangs William James Stillman’s 1858 Philosophers’ Camp in the Adirondacks, which came to the library in 1895 from the bequest of Ebenezer Rockwood Hoar. Both Emerson and Hoar are depicted among the campers in Philosophers’ Camp, with Emerson personifying the “transparent eyeball” of his slim first book, Nature.

In 1884, a marble carving from Daniel Chester French’s 1879 bust of Emerson from life was purchased for the library by subscription. It, too, is now on view in the Reference Room.

In addition, by the time French’s seated Emerson joined these three major pieces, the Concord Free Public Library had already gathered the nucleus of what would become a major archive of photographic portraits of Emerson (but that’s another story, and in some ways a much more complicated one, to be told another time).

The seated Emerson first became an object of public attention in 1896, a full eighteen years before it was finally unveiled. It was, essentially, a privately conceived and funded effort carried out with the blessing of the Town of Concord. At Town Meeting on April 6, 1896, the citizens of Concord approved the formation of a committee to arrange for the erection of a statue of Emerson “at some suitable place in Concord.” But the committee was not authorized to spend any town money. Its real task was private fund-raising.

It’s not clear from documentation here in the Special Collections exactly when the library became the designated site for the proposed memorial, but it appears that it was after 1910.

The original committee of five consisted of George A. King (who was then the Moderator of Town Meeting and the Chairman of the Town Library Committee, and who was the only original Statue Committee member still involved when the piece was unveiled in 1914); John Shepard Keyes; Samuel Hoar; T. Quincy Browne; and Edward Jarvis Bartlett.

The composition of the committee changed over time. In 1906, it was reorganized to include Woodward Hudson, Charles Francis Adams 2nd, George S. Keyes and non-Concord members Henry Lee Higginson of Boston (the founding benefactor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1881) and Moorfield Storey (a notable Boston lawyer, editor of the American Law Review, president of the American Bar Association, a pacifist, anti-imperialist, social reformer, civil rights advocate, and—from 1909 to 1929—the first president of the NAACP). A Harvard classmate of Emerson’s son Edward, Storey in particular represented the young men of the generation after Emerson’s who, influenced by his liberal idealism, threw themselves into progressive causes.

Why did it take so long for the committee to fulfill its charge, and why was it necessary ultimately to include people from beyond Concord? As you may have guessed, the answer has to do with money. The Statue Committee had a difficult time raising the significant amount of money required to create the memorial. On April 5, 1896, just after the official formation of the committee, in response to an inquiry from George King, Daniel Chester French wrote that his usual price for a portrait statue in bronze was between twelve and fifteen thousand dollars. And because the project took close to two decades to accomplish, the artist’s normal fees for his work had increased by the time he actively began the Emerson statue years later.

In Journey into Fame (her 1947 biography of her father), Margaret French Cresson wrote that the commission for the Emerson statue “touched Dan’s heart deeply.” In his youth, French had known Emerson, who was both a family friend and a relative by marriage. (Emerson’s daughter-in-law Annie Keyes Emerson—Edward’s wife—was related to the Frenches through the marriage of her uncle George Keyes to Mary Brown, daughter of Simon Brown and Daniel Chester French’s aunt Ann Caroline French Brown.)

Emerson had supported French’s commission to create the Minute Man statue as part of Concord’s commemoration of the 1875 centennial of the Concord Fight. And in the spring of 1879, French had gone into the Emerson home on the Cambridge Turnpike to model a bust of Emerson (a marble version of which is displayed in the Reference Room). French’s daughter later wrote, “Ever since he had made the bust, he had wondered what it would be like to undertake a statue . . . But he had known and loved Mr. Emerson so well that he was almost afraid to embark on it. It always seemed much harder to Dan to do a person that he knew than an unknown, where his imagination could more speedily run riot.”

Emerson had supported French’s commission to create the Minute Man statue as part of Concord’s commemoration of the 1875 centennial of the Concord Fight. And in the spring of 1879, French had gone into the Emerson home on the Cambridge Turnpike to model a bust of Emerson (a marble version of which is displayed in the Reference Room). French’s daughter later wrote, “Ever since he had made the bust, he had wondered what it would be like to undertake a statue . . . But he had known and loved Mr. Emerson so well that he was almost afraid to embark on it. It always seemed much harder to Dan to do a person that he knew than an unknown, where his imagination could more speedily run riot.”

But there’s more to the story than this. Although he was undoubtedly emotionally bound to Emerson and to Concord, French was no longer a struggling young artist in need of career-launching commissions. As a young man at the beginning of his career, he was grateful in 1873 to accept Concord’s commission for the Minute Man statue. As noted in the final printed report of the centennial celebration, he was at the time content to trust “all question of compensation for his design, other than the mere expense of construction, to the free will of the town.”

Initially honored though French was, however, he was ultimately disappointed. The Town belatedly awarded him the modest sum of one thousand dollars in 1876, but by then he had become more disillusioned (in his own words) by the “loss of faith in the righteousness of the Concord people than the actual loss of the money expected.” The Minute Man brought him early fame but not fortune. He was later more careful about payment.

Between the 1870s and the 1890s, a lot changed for French. For one thing, by 1896 he no longer lived and worked in Concord. He had studios in New York and the Berkshires. He had become a nationally recognized public artist and was much in demand around the country. He had created (among other works) the statue of John Harvard now located in Harvard Yard, the Thomas Gallaudet Memorial at Gallaudet College in Washington, D.C., and was at work on the Richard Morris Hunt Memorial in New York. Lorado Taft wrote of him in a January 1900 article in Brush and Pencil, “ . . . the sculptor has his hands full. I am glad of it. Every one of us rejoices in Mr. French’s prosperity. It means just that much more good art in our country.” With an established reputation, French no longer felt shy about naming his price for work in Concord.

The records of the Statue Committee show that by May 25, 1909—thirteen years after the committee was formed—only about $4,500 (including interest) had been raised. Evidently, not everyone felt enthusiasm for this project. In 1906, the committee issued a printed statement estimating that it required $25,000 altogether, but it appears from existing financial records that it never came near to reaching that goal.

In 1896, just after he was initially contacted by George King, French had suggested the possibility of creating the proposed statue in bronze. There had earlier been interest in placing an Emerson statue in the Boston Public Library, but the fundraising for that had not progressed very far. French consequently suggested to Concord’s Emerson Statue Committee that it might be more economical for Boston and Concord to join forces. He could model an Emerson statue from which a bronze copy for each place might be cast. But the suggestion was not taken, and fund-raising efforts for Concord’s statue continued.

A plea for donations appeared in the January 8, 1910 issue of The Springfield Republican. (Interestingly, in that piece the Statue Committee suggested that the San Francisco earthquake of 1906 had drawn off potential contributors to more pressing disaster relief.) Henry Lee Higginson invested donations to generate interest to augment the fund. Andrew Carnegie made a one thousand dollar gift. In the end, French was paid a total of $15,262.82 from donations and interest. It’s not clear from records here whether this covered the purchase of materials as well as the sculptor’s efforts.

In her biography of her father, Margaret French Cresson wrote that the seated Emerson took her father “the better part of two years” to produce once he began work in earnest. The larger piece presented challenges that the 1879 bust had not. While modeling the bust, French had the benefit of the living, breathing subject sitting before him. But Emerson died in 1882. Working on the seated Emerson in 1913, the sculptor had to rely on photographs together with his earlier bust as models. Because of its direct connection with its subject, a case can be made that the 1879 bust is more significant in terms of Emerson iconography. But the seated Emerson dominates this public space in a way that the more personal portrait cannot.

I urge you, when you have some time, to compare the two portraits of Emerson—the bust in the Reference Room and the seated figure here in the lobby. Each is affecting in its own way.

As mentioned, the marble bust was created in 1879, early in French’s career, just four years after the Minute Man was unveiled. French went to the Emerson House daily from March 1879 for about a month. He prepared a clay model from which plaster casts and—later—bronze copies were made. He also had two marble copies carved, one of them for the Concord Free Public Library.

The artist presented Emerson with a plaster cast from the master mold in July of 1879. The sage of Concord is famously reported to have said when he first saw it, “Dan, that’s the face I shave.” The face French presented is very human, lively and engaged. The piece is intimate—it looks as if Emerson were about to speak to the viewer. Since Emerson was mentally fading at the time he sat for the bust, it was not easy for French at this stage of his subject’s life to capture personality and vitality—the “lighting up” of Emerson’s face, as the artist described it.

In contrast, by the very fact that it’s a memorial work, the seated Emerson depicts a construct of Emerson as much as the man himself. Lawrence Buell has described Emerson as the “first modern American public intellectual,” and this piece reflects the full gravitas of that status. This Emerson is the embodiment of the Transcendental philosopher. The piece depicts its subject in middle age, at the prime of his powers. It was designed to be viewed from a distance. Emerson’s gaze does not quite meet the viewer’s—there’s a distance between the two. Emerson looks thoughtful, and kindly, and serene, and at the same time somewhat oracular. As he wrote in 1915, French worked to convey Emerson’s “elusive, illuminated expression . . . also, to perpetuate the peculiar sidewise thrust of the head . . . that was characteristic of him, conveying an impression of mental searching.”

The Emerson family lent French Emerson’s heavy robe—known as the “Gaberlunzie”— as a means of personalizing the statue. French incorporated it as drapery on the back of Emerson’s chair. He also included symbolism in the form of the pine boughs on Emerson’s right side. These represent the significance of nature in Emerson’s writings and reflect the fact that the pine was Emerson’s favorite tree.

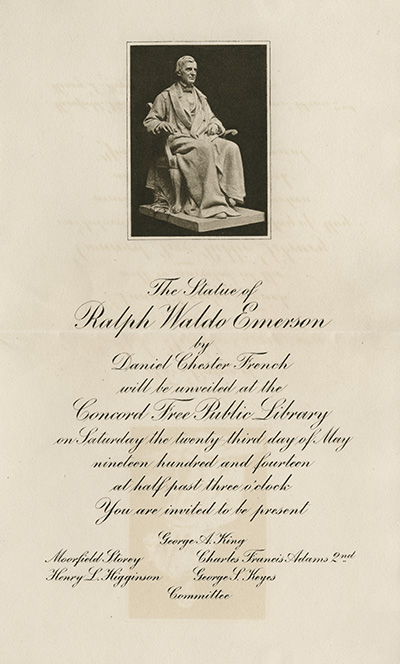

Once French had completed work, George King informed the Library Corporation that the seated Emerson was ready to ship. At its April 15, 1914 meeting, the Corporation voted to make preparations for the statue’s arrival, including the provision of adequate support for the floor beneath the massive piece. The Statue Committee set the date for the unveiling observances, issued invitations, and arranged the May 23, 1914 unveiling program.

Who was here that day? One Boston newspaper reported that because of space constraints, only those who had contributed to the Statue Fund and a small number of invited guests could be accommodated. (You have to remember that the library building then consisted almost entirely of what is now this lobby area.) Since the project had been endorsed by Town Meeting, I imagine that the exclusion of interested Concord residents raised a few eyebrows.

Members of the Statue Committee were here, of course. Henry Lee Higginson, Moorfield Storey, and George King all spoke. Members of the Library Corporation were among the invited guests. Murray Ballou, Chairman of Concord’s Board of Selectmen, represented the town. Edward Waldo Emerson and Edith Emerson Forbes—Emersons’s two surviving children—were present. His great-granddaughter Edith Forbes pulled the cord releasing the drapery over the statue.

Although he didn’t always attend unveilings of his work, Daniel Chester French was here, too. Whatever difficulties and delays the Statue Committee had experienced in raising money for his work, French was invested in the piece because of his personal connection with Emerson. Moreover, attendance at the unveiling allowed him to bask in the supportive embrace of friends who “remembered him when.”

Margaret French Cresson wrote in Journey Into Fame, “The unveiling of the Emerson in the library was most satisfactory. It looked well, the soft white marble was a beautiful material for the sensitive figure of the poet. Edward Emerson and Mrs. Forbes pronounced themselves immensely pleased and Dan’s lifelong friends crowded around and made a fuss over him. Usually such gatherings embarrassed him and he avoided them, but this was different; it was his own Concord, these were his friends and, though they admired the statue and revered the artist, what was still more important, they loved the man and it was a heart-warming experience.”

Concord’s reception of Daniel Chester French in May 1914 was not unlike that which Emerson himself had earlier enjoyed. Both men held the respect and admiration of the town, and, at the same time, enjoyed simple fellow-feeling on an elemental level.

Reminiscing about Emerson in 1915, French wrote, “The Concord of Emerson is a thing of the past. Its glory faded out with his life and, though it continued to be and still is a charming example of the New England town, peopled by charming and cultivated folk, the old-time aroma is lost and the spell is broken!” It was difficult for him to see at that moment that through the skill of his own hands as well as through Emerson’s words, the inspiration of the “golden age of classic Concord” (as he called it) would remain key to Concord’s identity. Emerson’s Transcendental idealism still serves as an impetus to thought and scholarship, bringing researchers here from near and far. Some come to the library as pilgrims to a shrine. Of course Concord is no longer as it was in Emerson’s time. Nevertheless, Emerson’s presence here played a part in shaping what it is now, and French’s seated Emerson holds a central and iconic place in helping all of us remember his legacy.

©2014 Concord Free Public Library. Permission required for use beyond brief attributed quotation.

Mounted 21 May2014 rcwh.